Sando (official)

Sando (alternately Sanduo, San To, Sadowo; Chinese: 三多; pinyin: Sānduō; Mongolian: Сандо; 1876-1941), courtesy name Liuqiao (Chinese: 六橋), was an official of the Qing dynasty and later the Republic of China who most served as the 62nd and last Qing Amban (昂邦 ; Resident Commissioner) of Outer Mongolia from 1909 to 1911. Although ethnically a Mongol, Sando's aggressive implementation of Beijing ordered reforms, including increased immigration of ethnic Han to the area and a rapid buildup of a sinicized military to fend off growing Russian influence, aggravated Mongols and precipitated moves by Khalkha nobles to declare independence from China in 1911.

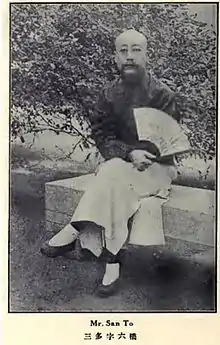

Sando 三多 | |

|---|---|

Sando in 1925 | |

| Amban of Outer Mongolia | |

| In office 1909–1911 | |

| Monarch | Xuantong Emperor |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1876 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, Qing China |

| Died | 1941 |

| Occupation | Qing Civil Servant |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

Early life

Sando was born in 1876 in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, as a member of the Plain White Mongol Banner. He studied under the prominent Chinese scholar Yu Yue, and later became a scholar himself. He is also believed to have studied in Japan for a period.[1] At a young age he entered the Manchu civil service and held several high level civil and military offices in Zhejiang, Beijing, and Hohhot. He served as prefect of the Hangzhou government, then was named Director of the Hangzhou Military Academy. In 1902, he moved to Beijing where he became proctor of the Imperial University. In 1907, he became a Counselor on the Board of Civil Administration. In 1908, he was appointed Fu du-tong (副都統), or Deputy Lieutenant-General in Guihua (present day Hohhot).[2] He would eventually write at least seven volumes of poetry and took a deep interest in the archeology and history of Mongolia.[3]

Amban of Urga

Sando was named Amban of Urga (modern day Ulaanbaatar) responsible for Tsetsen Khan and Tüsheet Khan aimags,[4] on November 26, 1909. Upon his arrival in March 1910, he implemented in rapid succession a spate of "New Administration" Qing reform policies and projects.[5] He promoted increased immigration of Han farmers, which he felt was a more effective way to counter expanding Russian influence in the area than simply garrisoning troops, and built up the Qing military capacity by establishing a Military Training Office under the domineering leadership of Army Chief of Staff Colonel Tang Zaili[1] (唐在礼) who forcibly recruited Mongolians, including lamas,[4] into the cavalry and local Chinese into the machine gun battalion.[6] To enforce law and order, Sando recruited 100 patrolmen and 44 policemen and levied taxes on gold, timber, carriage and camels to subsidize establishment of effective law courts. He introduced improvements to postal operations between Urga and Beijing, the education system, and to heath and sanitation (for example, he introduced street lights to the capital and created the first public toilets). He dispatched agents to investigate Outer Mongolia's natural resource potential, created the Bureau of Cultivation to exploit agricultural possibilities, especially in the central Tusheet Khan area of the country, and planned construction of a railway between the Urga and Beijing.[7]

Local Khalkha Mongols, unsettled by Sando's brutishness and the rapid pace of reforms, viewed these moves as little more than a purposeful colonization of the country. Sando's support suffered further following the Deyiyong Incident in April 1910. When a price dispute between Mongol monks and Chinese carpenters in Urga quickly devolved into a riot, Sando responded harshly, personally leading the armed response at Gandan Monastery, the principal monastery in the city. The protesting lamas pelted him and his troops with stones, forcing them to withdraw. Outraged, Sando demanded that the Mongolian spiritual leader, the Jebstundamba Khutuktu, surrender a particular lama believed to be the ringleader of the incident. The Khutuktu refused and Sando fined him. In response, representatives of the Jebstundamba Khutuktu petitioned the Qing government to remove Sando, but without success.[8]

Other incidents followed, all underscoring Sando's diminishing authority. A minor noble, Togtokh Taij, with a small band, had with the connivance of local Mongolian officials plundered several Chinese merchant shops in eastern Mongolia. Two detachments of soldiers sent by Sandoo to capture Togtokh were killed after being lured into a trap. Mongolian princes resisted providing soldiers for Sando's army. And the prince of the khoshuun which Togtokh had raided refused Sando's demand to pay compensation to the plundered Chinese merchants.[9]

Sando and his entire administration were eventually despised for their oppressive tactics. Opposition to Sando's administration continued to spread, in particular to Tang Zaili's heavy-handed attempts to tighten military control over Outer Mongolia. Tang's tactics eventually led to his recall after Mongolian leaders and the Russian Ambassador put pressure on Beijing. However, with Qing rule collapsing, Sando found support from Beijing dwindling. Believing that his position was untenable, Sando wired the Beijing government asking for permission to resign, but his request was denied.

Delegation to St. Petersburg

Sando's forcefulness was one factor in the decision of Mongolian nobles, among them Prince Tögs-Ochiryn Namnansüren, Da Lam Tserenchimed, and Mijiddorjiin Khanddorj, with the blessing of the Jebstundamba Khutuktu, to send a delegation to St. Petersburg in 1911 to seek Russian backing for Mongolian independence from China. In a letter to the Russian government, the Mongolian delegation accused the Qing of aggressive colonization of Outer Mongolia, creating Chinese administrative units, weakening the power of local Mongolian government institutions, and replacing Mongolian garrisons with Chinese troops along the Mongolian-Russian border. They proclaimed their intention declare independence to save their country from the fate of overt colonization by ethnic Chinese as suffered by their Inner Mongolian kinsmen.[1]

On learning of the Mongolian mission to Russia, the Qing government instructed Sando to investigate.[10] Sando immediately summoned the head of the Khutukhtu's ecclesiastical administration (Ikh shav’), the Erdene Shanzav Gonchigjalzangiin Badamdorj, and demanded an explanation. Badamdorj, pleading that he had not been involved, revealed the entire plot to Sando, who then demanded that the Khutuktu withdraw his request for Russian troops. The Khutuktu agreed, provided that Sando dismantle the New Administration. Sando cabled to Beijing for instructions, and was told that parts of the New Administration could be delayed.[11]

The moment was ripe for conciliation. Sando chose to bully instead. He ordered the princes in Urga to sign a statement that only a few individuals had been responsible for the appeal to Russia. The princes did give such a declaration, but only orally. Sando then ordered the Mongolians to have no further contact with the Russian consulate, threatening in case of disobedience to bring an additional 500 troops to Urga and to arm the Chinese population in the city. He posted sentries around the Khutuktu's palace with orders to bar Russian visitors. And he sent a contingent of troops to the Russian-Mongolian border to intercept the Mongolian delegation to Russia on its return.[12]

Mongolian independence

In the meantime, the Mongolian delegation to Russia secretly returned, and reported the results of its trip to a group of princes and lamas. They composed a joint memorial to the Khutukhtu asking what Mongolia should do in lieu of the provincial uprisings. He advised that Mongolians form a state of their own.[13] On December 1, 1911, a delegation of nobles and lamas visited Sando's office, and informed him of their decision to declare independence and to install the Khutuktu as emperor. Sando pleaded with the delegation. He admitted that what had come to pass was the result of his own folly, and he promised to recommend full autonomy for Mongolia, but not independence. The delegation curtly replied that it had come simply to deliver a message, not to debate it. Sando was ordered to leave the country within 24 hours.[4] There was little Sando could do. He had only 150 troops, who in any event were in an unruly mood because of arrears in back pay. On the following day, his soldiers were disarmed by Mongolian militiamen, as well as Russian Cossacks of the consular convoy under command of Grigory Semyonov, future Ataman. Sando and his staff moved into the Russian consulate compound for their own safety and then were escorted to the Russian border by Cossacks on December 5.[14]

After Mongolia

From there, Sando travelled to Mukden in Manchuria, where he received a telegram expressing the emperor's astonishment over Sando's inability to control the Mongols. The Amban was removed from office, and he was ordered to await an inquiry into his conduct. The fall of the Qing dynasty in February 1912 saved him from further embarrassment, or worse.[15]

Sando continued his public career in the newly established Republic of China. In October 1912 he was appointed Deputy Lieutenant-General in Mukden , and the following month he was concurrently named Deputy Lieutenant-General of Jinzhou. In September 1920, with the support of Zhang Zuolin he became the director of the Beijing Bureau of Emigration and Labor. In December 1921 he became Chief of the Bureau of Civil Appointments in the cabinet office. In June 1922 he was named Associate Director of the Famine Relief Bureau, and in October of the same year he was named head of the College of Marshals. Information about the last years of Sando's life is vague. However, it is believed he died in 1941 during the Second Sino-Japanese war.[2]

References

- Onon, Urgungge; Pritchatt, Derrick (1989). Asia's First Modern Revolution: Mongolia Proclaims Its Independence in 1911. BRILL. pp. 12–13. ISBN 9004083901.

- "Who's Who in China (1925) « Bibliotheca Sinica 2.0". www.univie.ac.at (in German). p. 646. Retrieved 2018-02-26.

- "Don Croner's World Wide Wanders Part 1". worldwidewanders1.blogspot.sg. Retrieved 2018-03-03.

- Batbayar (Baabar), Bat-Erdene (1999). Twentieth Century Mongolia. Cambridge: White Horse Press. p. 139. ISBN 1-874267-40-5.

- Adle, Chahryar (2005-01-01). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Towards the contemporary period : from the mid-nineteenth to the end of the twentieth century. UNESCO. p. 356. ISBN 9789231039850.

- Natsagdorj, Sh. (1963). Manjiin erkhsheeld baisan üyeiin Khalkhyn khurangui tüükh (1691–1911) [The history of Khalka under the Manchus]. Ulaanbaatar. p. 173.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kotkin, Stephen; Elleman, Bruce Allen (2015-02-12). Mongolia in the Twentieth Century. Routledge. p. 47. ISBN 9781317460091.

- Ewing, Thomas E. (1978). Thomas E. Ewing, Revolution on the Chinese Frontier: Outer Mongolia in 1911, Journal of Asian History, v. 12. p. 106.

- Chen, Lu (1919). Jrshi biji [Reminiscences]. Shanghai. p. 179.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Onon, Urgungge; Pritchatt, Derrick (1989). Asia's First Modern Revolution: Mongolia Proclaims Its Independence in 1911. BRILL. p. 7. ISBN 9004083901.

- Chen, Lu (1919). Jrshi biji [Reminiscences]. Shanghi. p. 185.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Die Internationalen Beziehungen im Zeitalter des Imperialismus [International Relations in the Age of Imperialism]. Berlin. 1931. p. 495.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dendev, L (1934). Monglyn tovch tüükh [Short history of Mongolia]. Ulaanbaatar. pp. 19–21.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sanders, Alan J. K. (2010-05-20). Historical Dictionary of Mongolia. Scarecrow Press. p. 349. ISBN 9780810874527.

- Chen, Chungzu (1926). Waimenggu jinshi shi [The recent history of Mongolia]. p. 13.