Santa Ana (canton)

Santa Ana is the ninth canton in the San José province of Costa Rica.[3][4] It is located in the Central Valley. It borders with the Alajuela canton to the north, the Mora canton to the south and west, the Escazú canton to the east, as well as the Belén canton to the north east.[5] As of 2020, the canton has the highest Human Development Index of any region in Costa Rica with a HDI of 0.871.[6]

Santa Ana | |

|---|---|

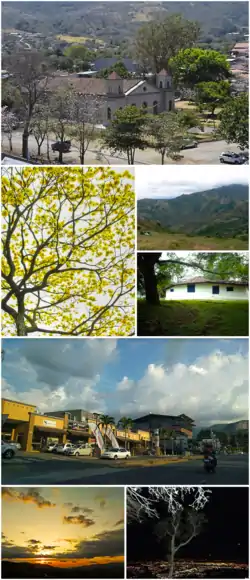

From the top, left to right: The Saint Anne parish church, a Roble Sabana, the Escazú mountains as seen from the Salitral district, the Santa Ana Conservation Centre, a shopping centre, a view of the sunset in the Piedades district, a view of Santa Ana at night. | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nicknames: Valle del Sol [1] Spanish for: "Valley of the Sun" | |

Santa Ana canton | |

Santa Ana Santa Ana canton location in San José Province  Santa Ana Santa Ana canton location in Costa Rica | |

| Coordinates: 9.9184253°N 84.1957531°W | |

| Country | |

| Province | San José |

| Creation | 29 August 1907[2] |

| Head city | Santa Ana |

| Districts | |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| • Body | Municipalidad de Santa Ana |

| • Mayor | Gerardo Oviedo Espinoza (PLN) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 61.42 km2 (23.71 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 904 m (2,966 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 49,123 |

| • Density | 800/km2 (2,100/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Santaneño, -a |

| Time zone | UTC−06:00 |

| Canton code | 109 |

| Website | www |

Toponymy

The first mention of the name appears in the Protocols of Cartago on December 1, 1658, when part of the land which now conforms the canton became property of José de Alvarado and Petronilla de Retes after their marriage. The name of the lands comes from the original owner, Jerónimo de Retes y López de Ortega, father of Petronilla. Ortega was seeded the land in the 17th century by the Spanish crown as recognition for his work as an official in Cartago. It is theorised that the lands were named in honour of Saint Anne, possibly because Ortega had a special affinity with the saint (as he would later name his daughter Ana de Retes after the saint as well).[7][8][9]

History

Precolombian and Early History

The earliest known occupied settlements in the region can be dated to the 3rd century, with the land that now conforms the canton being part of the indigenous Reino Huetar de Occidente (The Huetar kingdom of the west). At the time of the Spanish's arrival in the 16th century, this kingdom was one of two indigenous kingdoms ruled by the cacique Garabito.[1] A total of 11 archaeological sites can be found in the canton.[10]

After Christopher Columbus's arrival on the Costa Rican coast in 1502, the Spanish made very little travel into Costa Rica. However, in 1559, after being awarded a royal license by Philip II of Spain, the at the time governor of Nicaragua, Juan de Cavallón y Arboleda, planned to colonise the region (at the time known as Nuevo Cartago y Costa Rica), specifically the pacific coast. However this failed, and thus in January 1561, with an expedition formed of 80 spainards, livestock and slaves, Cavallón entered from Nicaragua into the inland of Costa Rica. His expedition passed near the location of modern-day Puntarenas. While camping further inland, Arboleda sent out multiple hunting parties, one of which managed to capture an indigenous chief of the Chorotega tribe named Coyote, who agreed to guide Cavallón and his men further inland. After this the exact route of the conquistadors is unknown, however the leading historical theory states that the men passed by the modern day location of Santiago de Puriscal, before entering the Santa Ana Valley. It is thought that here, Arboleda founded the first Spanish city in the wider Costa Rican central valley, named Castillo de Garcimuñoz, after Cavallón's birthplace. The exact location of the settlement has been debated, and it has been suggested that the location is further east near modern-day Desamparados. Soon afterwards however, due to constant raids by local tribes, and possibly due to the lack of slave labour, many left the settlement. Cavallón would leave the colony in 1562, possibly discouraged by the lack of gold deposits in the region. The settlement was mostly abandoned after 3 years of its founding. Afterwards, a group led by Don Antonio de Pereira would also reach the lands that are currently part of the canton, reaching the Santa Ana hills.[7][9][11]

The lands of the canton were further colonised in the 17th century after the lands which now conform the canton were seeded to a former official of Cartago named Jerónimo de Retes y López de Ortega as recognition for his work. Ortega would name his lands in honour of Saint Anne. In 1658 however, part of the land would be given to Petronilla de Retes (Ortega's Daughter) and her husband José de Alvarado after their marriage. Soon afterwards the land would pass to Petronilla's sister, Ana de Retes. Part of the land would be sold in 1750 by the Retes family, with a house (Known as "La Casona", which still stands in modern day) and a chapel being built.[9]

By 1817, most of the land had come into possession of Ana María de Cárdenas. However, by 1850, the lands had changed hands multiple times, eventually ending up in the hands of a priest named Ana Tiburcio Fernández Valverde. Valverde would subsequently remodel the old chapel, converting it into a small hermitage, which would open in 1850. By 1870, the current parish church of Santa Ana began construction, with it finalising in 1880. Around this time, the modern day head city of canton (Santa Ana), also began to arise around the Fernández property, along the Uruca river. By 1880, the centre of the future district had moved east.[7][9][12][13]

In 1870 the mayoral office of Santa Ana is established, with Cerlindo Villarreal serving as the town first mayor. The town only had 1.068 residents at the time.[12] Soon afterwards, the first school would be built in 1873. In 1890, an hacienda known as "Hacienda Ross" (after its original owner, an Englishman named Robert Ross Lang) would become the first ever Costa Rican settlement for railway workers, due to the good relationship between the railroad builder, Minor Kieth, and the Ross family.[7][9]

Independence From Escazu and Modern History

On the 29 of August 1907, under law no.8, Santa Ana was awarded the title of canton, becoming fully independent from Escazú. The first session of the new council was held on the 15th of September that same year.

In 1908, a contract was signed to build Costa Rica's second hydroelectric plant in the canton, with it being finished it 1912. Electric streetlights would arrive the following year. Around 1915, it is believed that onions were introduced to the canton, they would quickly become Santa Ana's most famous crop, with Santa Ana citizens being given the nickname of "Cebolleros" (onion farmers). Santa Ana holds an Onion fair even in modern times.[9][14] After the military coup of Federico Tinoco Granados in 1917, Santa Ana would become a mayor stronghold for rebellion against the government. Among the leaders of this rebillion was Jorge Volio Jiménez, a priest who was honoured with a head bust outside of the Municipal Palace of Santa Ana. Jimenez's rule would only lasted 2 years, with him being deposed in 1919. Costa Rica's first international airport would open in the canton, in the barrio of Lindora, in 1931, with the town soon being modernized into an international gateway for the country around 1934. The country's main airport would be moved to La Sabana in 1940.[9]

During the 1948 Costa Rican Civil War, Santa Ana would once again serve as a rebellion stronghold, in this case for rebel leader Jose Figueres Ferrer. One of the leading figures in the revolution from Santa Ana was a man from Honduras named Marcial Aguiluz Orellana, who would later help defeat a counter revolution by Rafael Angel Calderón Guardia in 1955, and would eventually join the legislative assembly of Costa Rica. He would die in 1986. The first automatic telephone would arrive in the canton in 1966. Soon after on the 4 May 1970, Santa Ana was officially declared a city under the municipal code, and would become the seat for the Santa Ana canton. In 1971, the name of "Valley of the Sun" would be adopted by the municipality after being used as a traditional nickname for the canton for years.[4][9] In 2020, the canton would obtain the highest HDI in the country with an ranking of 0.871.[6]

Geography

Santa Ana has an area of 61.42 km2[15] and a mean elevation of 904 metres.[3]

The triangular-shaped canton is delineated by the Virilla River on the north and stretches south as it narrows to include a portion of the Cerros de Escazú.

Districts

The canton of Santa Ana is subdivided into the following districts:

| Districts of the Santa Ana Canton | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | District | Area (km²) | Elevation[4] | Population (2020)[16] | |

| 1 | Santa Ana | 5.4 | 904 m | 12 878 |  |

| 2 | Salitral | 20.2 | 1022 m. | 5 421 | |

| 3 | Pozos | 13.34 | 847 m. | 20 094 | |

| 4 | Uruca | 7.07 | 873 m. | 8 899 | |

| 5 | Piedades | 12.01 | 899 m | 10 014 | |

| 6 | Brasil | 3.25 | 878 m | 3 150 | |

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1927 | 3,785 | — | |

| 1950 | 5,812 | 53.6% | |

| 1963 | 9,026 | 55.3% | |

| 1973 | 14,499 | 60.6% | |

| 1984 | 19,605 | 35.2% | |

| 2000 | 34,507 | 76.0% | |

| 2011 | 49,123 | 42.4% | |

|

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos[17] |

|||

For the 2011 census, Santa Ana had a population of 49,123 inhabitants.[19]

Transportation

Road transportation

The canton is covered by the following road routes:

Culture

Flag

Adopted by the municipal council of the canton on 22 April 1987, the flag consists of three symetrical horizontal stripes. The top most green stripe represents the canton's nature and fields, the middle yellow stripe represents the sun (as the canton and the valley it resides in has been nicknamed "The Valley of the Sun"), and the lower most pink stripe representing the colour of the flowers of the Roble Savanna, another of the canton's symbols.[1][20]

Roble de Sabana

.jpg.webp)

The Tabebuia rosea (nicknamed "Roble de Sabana", meaning Savannah Oak) is native to Costa Rica, and can be seen in the country's warm areas.[21] It was declared a symbol of the canton by Santa Ana's Municipal Council in ordinary session n.267 held on June 23, 2015. The tree can also be seen of the canton's seal and flag.[1]

The onion

It is believed that the onion was introduced to the canton in 1915, and became a facet of farmers' cultivations soon after. By 1970, a total of 200 hectares of onion plantations were seen in the canton. However with the regions urbanisation, that number has dropped to around 50 hectares in mordern times, however the canton still celebrates an onion fair around March, when the region sees its highest production of the vegetable.[9][14][22]

Notable people

This is a list of people born or that have lived in Santa Ana.

- Marcia González Aguiluz: Lawyer with an emphasis on environmental law. She was the president of the Citizens' Action Party between 2017 and 2018, as well as former minister of justice and peace under president Carlos Alvarado Quesada.

- María Luisa Ávila Agüero: A Pediatric subspecializing in infectious diseases who was the minister of health under presidents Óscar Arias Sánchez and Laura Chinchilla.

- Michael Umaña: Former football player who played as a defender.

- Carlos Martínez: Football player who currently plays at A.D. San Carlos as a defender.

- Marcial Aguiluz Orellana: A Honduran farmer who would join the Costa Rican legislative assembly on two occasions. He was a rebel figure in the 1948 civil war. He lived and died in the canton.

References

- "El Cantón". santaana.go.cr (in Spanish). Gobierno local de Santa Ana. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- Hernández, Hermógenes (1985). Costa Rica: evolución territorial y principales censos de población 1502 - 1984 (in Spanish) (1 ed.). San José: Editorial Universidad Estatal a Distancia. pp. 164–173. ISBN 9977-64-243-5. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- "Declara oficial para efectos administrativos, la aprobación de la División Territorial Administrativa de la República N°41548-MGP". Sistema Costarricense de Información Jurídica (in Spanish). 19 March 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- División Territorial Administrativa de la República de Costa Rica (PDF) (in Spanish). Editorial Digital de la Imprenta Nacional. 8 March 2017. ISBN 978-9977-58-477-5.

- "Santa Ana" (PDF). Bibloteca Virtual en Poblacion, Centroamericano de Poblacion (in Spanish). Instituto de Fomento y Asesoría Municipal. 1985. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- "Atlas de desarrollo humano cantonal, 2021". unpd.org (in Spanish). United Nations Development Programme Costa Rica. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- "SANTA ANA CANTÓN 1- 09". Ifam.go.cr (in Spanish). Instituto de Fomento y Asesoria Municipal. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- Aguilar, Ana Yancy. "Conozca el origen del nombre del cantón de Santa Ana" (in Spanish). Amprensa. Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- "Santa Ana history: Was this Spain's first town in the Central Valley?". The Tico Times. July 7, 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- "Búsqueda de Sitios Arqueológicos". origenes.museocostarica.go.cr (in Spanish). Museo Nacional de Costa Rica. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- Nelson, H. D (1983). Costa Rica, a country study / Foreign Area Studies, the American University ; edited by Harold D. Nelson (2nd ed.). Washington D.C: Headquarters, Dept. of the Army. p. 9. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- "Hace 115 años Santa Ana fue declarado cantón". santaanahoy.com (in Spanish). Santa Ana Hoy. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- "Historia". parroquiasantaana-cr.org (in Spanish). Parroquia de Santa Ana. Retrieved 20 October 2023.

- "Pueblo Cebollero". parroquiasantaana-cr.org (in Spanish). Parroquia de Santa Ana. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- "Área en kilómetros cuadrados, según provincia, cantón y distrito administrativo". Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (in Spanish). Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- "Santa Ana". City Population. 4 July 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- "Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos" (in Spanish).

- "Sistema de Consulta de a Bases de Datos Estadísticas". Centro Centroamericano de Población (in Spanish).

- "Censo. 2011. Población total por zona y sexo, según provincia, cantón y distrito". Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (in Spanish). Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- "Santa Ana (San Jose, Costa Rica)". crwflags.com. Flags of the World. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- "Roble Sabana". costaricagardens.com (in Spanish). Costa Rica Gardens. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- "Breve reseña" (PDF). simposiointernacionalarteytradicion.files.wordpress.com. Asociación Escultórica Valle del Sol (AEVaS). Retrieved 17 October 2023.