Sapphic stanza

The Sapphic stanza, named after Sappho, is an Aeolic verse form of four lines. Originally composed in quantitative verse and unrhymed, since the Middle Ages imitations of the form typically feature rhyme and accentual prosody. It is "the longest lived of the Classical lyric strophes in the West".[1]

Definitions

In poetry, "Sapphic" may refer to three distinct but related Aeolic verse forms:[1]

- The greater Sapphic, a 15-syllable line, with the structure:

– u – – – | u u – | – u u – u – –

–=long syllable; u=short syllable; |=caesura - The lesser Sapphic, an 11-syllable line, with the structure:

– u – x – u u – u – –

x=anceps (either long or short) - The Sapphic stanza, typically conceptualized as comprising 3 lesser Sapphic lines followed by an adonic, with the structure:

– u u – –

Classical Latin poets duplicated the Sapphic stanza with subtle modification.

Since the Middle Ages the terms "Sapphic stanzas" or frequently simply "Sapphics" have come to denote various stanzaic forms approaching more or less closely to Classical Sapphics, but often featuring accentual meter or rhyme (neither occurring in the original form), and with line structures mirroring the original with varying levels of fidelity.[1][2]

Aeolic Greek

Alcaeus of Mytilene composed in, and may have invented, the Sapphic stanza,[1] but it is his contemporary and compatriot Sappho whose example exerted the greatest influence, and for whom the verseform is now named. Both lived around 600 BCE on the island of Lesbos and wrote in the Aeolic dialect of Greek.

The original Aeolic verse takes the form of a 3-line stanza:[1]

– u – x – u u – u – –

– u – x – u u – u – –

– u – x – u u – u – x – u u – –

–=long syllable; u=short syllable; x=anceps (either long or short)

However, these stanzas are frequently analyzed as 4 lines, thus:[1]

– u – x – u u – u – –

– u – x – u u – u – –

– u – x – u u – u – x

– u u – –

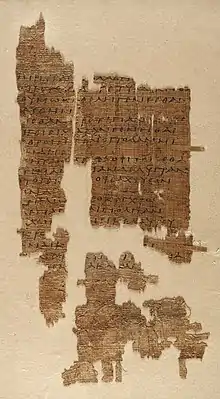

While Sappho used several metrical forms for her poetry, she is most famous for the Sapphic stanza. Her poems in this meter (collected in Book I of the ancient edition) ran to 330 stanzas, a significant part of her complete works, and of her surviving poetry: fragments 1-42.

Sappho's most famous poem in this metre is Sappho 31, which begins as follows:

Φαίνεταί μοι κῆνος ἴσος θέοισιν

ἔμμεν ὤνηρ ὄττις ἐνάντιός τοι

ἰζάνει καὶ πλάσιον ἆδυ φωνεί-

σας ὐπακούει[3]— Fragment 31, lines 1-4

(In this stanza, all anceps positions are filled with long syllables.) Transliteration and formal equivalent paraphrase (substituting English stress for Greek length):

phaínetaí moi kênos ísos théoisin |

He, it seems to me, is completely godlike: |

Latin

Classical

A few centuries later, the Roman poet Catullus admired Sappho's work and used the Sapphic stanza in two poems: Catullus 11 (commemorating the end of his affair with Clodia) and Catullus 51 (marking its beginning).[4] The latter is a free translation of Sappho 31.[5]

Horace wrote several of his Odes in Sapphics, and two tendencies of Catullus became normative practice with Horace: the occurrence of a caesura after the fifth syllable; and the fourth syllable (formerly anceps) becoming habitually long.[6][7] Horace's Odes became the chief models for subsequent Sapphics, whether in Latin[8] or the later vernaculars — hence the term "Horatian Sapphic" for this modified model. But due to linguistic change, Horace's imitators split on whether they imitated his quantitative structure (the long and short syllables, Horace's metrical foundation), or his accentual patterns (the stressed or unstressed syllables which were somewhat ordered, but not determinative of Horace's actual formal structure).[9] Gasparov provides this double scansion of Ode 1.22 (lines 1-4), which also displays Horace's typical long forth syllables and caesura after the fifth:

/ × × / × × × / × / × – u – – – u u – u – ∩ Integer vitae | scelerisque purus × / × / × / × × × / × – u – – – u u – u – – Non eget Mauris | iaculis, neque arcu, × × × / × / × × × / × – u – – – u u – u – – Nec venenatis | gravida sagittis, / × × / × – u u – – Fusce, pharetra...[9] /=stressed syllable; ×=unstressed syllable; ∩=brevis in longo

Other ancient poets who used the Sapphic stanza are Statius (in Silvae 4.7), Prudentius, Ausonius, Paulinus of Nola and Venantius Fortunatus (once in Carmina 10.7).[8]

Usually, the lesser Sapphic line is found only within the Sapphic stanza; however, both Seneca the Younger (in his Hercules Oetaeus) and Boethius used the line in extended passages (thus resembling the stichic quality of blank verse more than a stanzaic lyric).[10]

Medieval

The Sapphic stanza was one of the few classical quantitative meters to survive into the Middle Ages, when accentual rather than quantitative prosody became the norm. Many Latin hymns were written in Sapphic stanzas, including the famous hymn for John the Baptist which gave the original names of the sol-fa scale:

Ut queant laxīs | resonāre fibrīs

Mīra gestōrum | famulī tuōrum

Solve pollūtī | labiī reātum

Sāncte Ioannēs

Accentual Sapphic stanzas that ignore Classical Latin vowel quantities are also attested, as in the 11th-century Carmen Campidoctoris, which stresses the 1st, 4th and 10th syllables of the lines while keeping the Horatian caesura after the fifth (here with a formal equivalent paraphrase):

Talibus armis | ornatus et equo |

Furnished with all these munitions and stallion, |

| —Carmen Campidoctoris, Stanza 32 |

English

Though some English poets attempted quantitative effects in their verse, quantity is not phonemic in English. So, imitations of the Sapphic stanza are typically structured by replacing long with stressed syllables, and short with unstressed syllables (and often additional alterations, as exemplified below).

The Sapphic stanza was imitated in English, using a line articulated into three sections (stressed on syllables 1, 5, and 10) as the Greek and Latin would have been, by Algernon Charles Swinburne in a poem he simply called "Sapphics":

So the goddess fled from her place, with awful

Sound of feet and thunder of wings around her;

While behind a clamour of singing women

Severed the twilight.[12]— "Sapphics", stanza 6

Thomas Hardy chose to open his first verse collection Wessex Poems and other verses 1898 with "The Temporary the All", a poem in Sapphics, perhaps as a declaration of his skill and as an encapsulation of his personal experience.

Change and chancefulness in my flowering youthtime,

Set me sun by sun near to one unchosen;

Wrought us fellowly, and despite divergence,

Friends interblent us.[13]— "The Temporary the All", lines 1-4

Rudyard Kipling wrote a tribute to William Shakespeare in Sapphics called "The Craftsman". He hears the line articulated into four, with stresses on syllables 1, 4, 6, and 10 (despite being called a "schoolboy error" by classical scholar L. P. Wilkinson due to Horace's regularisation of the 4th syllable as a long, stressing the 4th-syllable was a common approach in several Romance languages[14]). His poem begins:

Once, after long-drawn revel at The Mermaid,

He to the overbearing Boanerges

Jonson, uttered (if half of it were liquor,

Blessed be the vintage!)[15]— "The Craftsman", lines 1-4

Allen Ginsberg also experimented with the form:

Red cheeked boyfriends tenderly kiss me sweet mouthed

under Boulder coverlets winter springtime

hug me naked laughing & telling girl friends

gossip til autumn[16]— "τεθνάκην δ' ὀλίγω 'πιδεύης φαίνομ' ἀλαία", lines 1-4

The Oxford classicist Armand D'Angour has created mnemonics to illustrate the difference between Sapphics heard as a four-beat line (as in Kipling) versus the three-beat measure, as follows:

Sapphics A (4 beats per line):

Cőnquering Sáppho's nőt an easy búsiness:

Masculine ladies cherish independence.

Only good music penetrates the souls of

Lesbian artists.[17]

Sapphics B (correct rhythm, 3 beats per line):

Índependent métre is overráted:

What's the use if nobody knows the verse-form?

Wisely, Sappho chose to adopt a stately

regular stanza.[17]

Notable contemporary Sapphic poems include "Sapphics for Patience" by Annie Finch, "Dusk: July" by Marilyn Hacker, "Buzzing Affy" (a translation of "An Ode to Aphrodite") by Adam Lowe, and "Sapphics Against Anger" by Timothy Steele.

Other languages

Written in Latin, the Sapphic stanza was already one of the most popular verseforms of the Middle Ages, but Renaissance poets began composing Sapphics in several vernacular languages, preferring Horace as their model above their immediate Medieval Latin predecessors.[1]

Leonardo Dati composed the first Italian Sapphics in 1441, followed by Galeotto del Carretto, Claudio Tolomei, and others.[1]

The Sapphic stanza has been very popular in Polish literature since the 16th century. It was used by many poets. Sebastian Klonowic wrote a long poem, Flis, using the form.[18] The formula of 11/11/11/5 syllables[19] was so attractive that it can be found in other forms, among others the Słowacki stanza: 11a/11b/11a/5b/11c/11c.[20]

In 1653, Paul Gerhardt used the Sapphic strophe format in the text of his sacred morning song "Lobet den Herren alle, die ihn ehren". Sapphic stanza was often used in poetry of German Humanism and Baroque. It is also used in hymns such as "Herzliebster Jesu" by Johann Heermann. In the 18th century, amidst a resurgence of interest in Classical versification, Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock wrote unrhymed Sapphics, regularly moving the position of the dactyl.[1]

Esteban Manuel de Villegas wrote Sapphics in Spanish in the 17th century.[1]

Miquel Costa i Llobera wrote Catalan Sapphics in the late 19th century, in his book of poems in the manner of Horace, called Horacianes.[21]

Notes

- Swanson, Brogan & Halporn 1993, p. 1113.

- Hamer 1930, pp. 302–310.

- Edmonds 1922, p. 186.

- Quinn 1973, pp. 125, 241.

- Quinn 1973, p. 241.

- Quinn 1973, p. 127.

- Halporn, Ostwald & Rosenmeyer 1994, p. 100.

- Heikkinen 2012, p. 148.

- Gasparov 1996, p. 86.

- Halporn, Ostwald & Rosenmeyer 1994, p. 101.

- Montaner & Escobar 2000, p. 5, § Edición crítica.

- Swinburne 1866, p. 236.

- Hardy 1899, p. 1.

- Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo, Horacio en España (1885 ed, Madrid,) p. 313.

- Kipling c. 1919, p. 400.

- Ginsberg 1988, p. 735.

- D'Angour n.d.

- Pszczołowska 1997, p. 77.

- Sierotwiński 1966, p. 258.

- Darasz 2003, pp. 145–146.

- "Diccionari de la Literatura Catalana".

References

- Main

- Darasz, Wiktor Jarosław (2003). Mały przewodnik po wierszu polskim. Kraków. ISBN 9788390082967. OCLC 442960332.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gasparov, M. L. (1996). Smith, G. S.; Holford-Strevens, L. (eds.). A History of European Versification. Translated by Smith, G. S.; Tarlinskaja, Marina. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-815879-3. OCLC 1027190450.

- Halporn, James W.; Ostwald, Martin; Rosenmeyer, Thomas G. (1994) [1980]. The Meters of Greek and Latin Poetry (Rev. ed.). Indianapolis: Hackett. ISBN 0-87220-243-7. OCLC 690603221.

- Hamer, Enid (1930). The Metres of English Poetry. London: Methuen. pp. 302–310. OCLC 1150304609.

- Heikkinen, Seppo (2012). The Christianization of Latin Metre: A Study of Bede's De arte metrica [PhD diss.] (PDF). Helsinki: Unigrafia. pp. 147–152. ISBN 978-952-10-7807-1.

- Pszczołowska, Lucylla (1997). Wiersz polski: Zarys historyczny. Wrocław. ISBN 9788388631047. OCLC 231947750.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Quinn, Kenneth, ed. (1973). Catullus: The Poems (2nd ed.). London: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-333-01787-0. OCLC 925241564.

- Sierotwiński, Stanisław (1966). Słownik terminów literackich. Wrocław. OCLC 471755083.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Steele, Timothy (1999). All the Fun's in How you Say a Thing : an explanation of meter and versification. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. ISBN 0-8214-1260-4. OCLC 1051623933.

- Swanson, Roy Arthur; Brogan, T.V.F.; Halporn, James W. (1993). "Sapphic". In Preminger, Alex; Brogan, T.V.F.; et al. (eds.). The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. New York: MJF Books. p. 1113. ISBN 1-56731-152-0. OCLC 961668903.

- Verse specimens

- D'Angour, Armand (n.d.). "Mnemonics for metre". www.armand-dangour.com. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- Edmonds, J. M., ed. (1922). Lyra Graeca, Volume I: Terpander, Alcman, Sappho and Alcaeus. Loeb Classical Library (#142). London: William Heinemann.

- Ginsberg, Allen (1988). Collected Poems, 1947-1980. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-091494-3.

- Hardy, Thomas (1899). Wessex Poems and other verses. New York and London: Harper & Brothers. OCLC 503311523.

- Kipling, Rudyard (c. 1919). Rudyard Kipling's Verse : inclusive ed., 1885-1918. Toronto: Copp Clark. OCLC 697598774.

- Montaner, Alberto; Escobar, Angel (2000). "Carmen Campidoctoris o poema latino del Campeador [preprint version]". Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- Swinburne, Algernon Charles (1866). Poems and Ballads. London: John Camden Hotten. OCLC 459165016.

- Wickham, E[dward] C[harles], ed. (1912). The Odes of Horace : Books I-IV and the Saecular Hymn. Translated by Marris, William Sinclair. London: Oxford University Press. OCLC 1000697823.

External links

- http://www.aoidoi.org/articles/meter/intro.pdf

- https://digitalsappho.org/fragments-2/

- Shorey, Paul (1907). "Word-Accent in Greek and Latin Verse". The Classical Journal. 2 (5): 219–224.

.jpg.webp)