Capture of Savannah

The Capture of Savannah, sometimes the First Battle of Savannah (because of the siege of 1779), or the Battle of Brewton Hill,[3][4] was an American Revolutionary War battle fought on December 29, 1778 pitting local American Patriot militia and Continental Army units, holding the city, against a British invasion force, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell. The British capture of the city led to an extended occupation and was the opening move in the British southern strategy to regain control of the rebellious Southern provinces by appealing to the relatively strong Loyalist sentiment there.

| Battle of Savannah | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell (portrait by George Romney, c. 1792) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

850 infantry and militia 4 guns[1] |

3,500 infantry and militia unknown artillery[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

83 killed 11 wounded 453 captured[2] |

7 killed 17 wounded[2] | ||||||

General Sir Henry Clinton, the Commander-in-Chief, North America, dispatched Campbell and a 3,100-strong force from New York City to capture Savannah, and begin the process of returning Georgia to British control. He was to be assisted by troops under the command of Brigadier General Augustine Prevost that were marching up from Saint Augustine in East Florida. After landing near Savannah on December 23, Campbell assessed the American defenses, which were comparatively weak, and decided to attack without waiting for Prevost. Taking advantage of local assistance he flanked the American position outside the city, captured a large portion of Major General Robert Howe's army, and drove the remnants to retreat into South Carolina.

Campbell and Prevost followed up the victory with the capture of Sunbury and an expedition to Augusta. The latter was occupied by Campbell only for a few weeks before he retreated to Savannah, citing insufficient Loyalist and Native American support and the threat of Patriot forces across the Savannah River in South Carolina. The British held off a Franco-American siege in 1779, and held the city until late in the war.

Background

In March 1778, following the defeat of a British army at Saratoga and the consequent entry of France into the American Revolutionary War as an American ally, Lord George Germain, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, wrote to General Sir Henry Clinton that capturing the southern colonies was "considered by the King as an object of great importance in the scale of the war".[5] Germain's instructions to Clinton, framed as recommendations, were that he should abandon Philadelphia and then embark upon operations to recover Georgia and the Carolinas; whilst making diversionary attacks against Virginia and Maryland.[6]

British preparations

In June and July 1778 Clinton removed his troops from Philadelphia back to New York.[7] In November, after dealing with the threat of a French fleet off New York and Newport, Rhode Island, Clinton turned his attention to the South. He organized a force of about 3,000 men in New York and sent orders to Saint Augustine, the capital of East Florida, where Brigadier General Augustine Prevost was to organize all available men and Indian agent John Stuart was to rally the local Creek and Cherokee warriors to assist in operations against Georgia.[8] Clinton's basic plan, first proposed by Thomas Brown in 1776, began with the capture of the capital of Georgia, Savannah.[9]

Clinton gave command of the detachment from New York to Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell. The force consisted of two battalions (the 1st and 2nd) of the 71st Regiment of Foot, the Hessian regiments von Wöllwarth and von Wissenbach, and four Loyalist units: one battalion from the New York Volunteers, two from DeLancey's Brigade, and one from Skinner's Brigade. Campbell sailed from New York on November 26 and arrived off Tybee Island, near the mouth of the Savannah River, on December 23.[10]

American defenses

The State of Georgia was defended by two separate forces. Units of the Continental Army were under the command of Major General Robert Howe, who was responsible for the defense of the entire South, and the state's militia companies were under the overall command of Georgia Governor John Houstoun. Howe and the Georgia authorities had previously squabbled over control of military expeditions against Prevost in East Florida, and those expeditions had failed.[11] These failures led the Continental Congress to decide in September 1778 to replace Howe with Major General Benjamin Lincoln, who had negotiated militia participation in events surrounding the British defeat at Saratoga.[12] Lincoln had not yet arrived when word reached Howe that Clinton was sending troops to Georgia.

In November 1778, British raids into Georgia became more and more threatening to the state's population centers.[13] Despite the urgency of the situation, Governor Houstoun refused to allow Howe to direct the movements of the Georgia Militia. On November 18, Howe began marching south from Charleston, South Carolina with 550 Continental Army troops, arriving in Savannah late that month. He learned that Campbell had sailed from New York on December 6. On December 23, sails were spotted off Tybee Island. The next day, Governor Houstoun assigned 100 Georgia militia to Howe.[14]

A council of war decided to attempt a vigorous defense of Savannah although it was thought that they were likely to be significantly outnumbered by the British and hoped to last until Lincoln's troops arrived. The large number of potential landing points forced Howe to hold most of his army in reserve until the British had actually landed.[15]

Order of battle

Continentals

- Commanding Officer, Major General Robert Howe

- 4th Georgia Regiment

- 500–550 Georgia and South Carolina Militia led by Brigadier General Isaac Huger

British

- Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Sir Archibald Campbell

- 71st Regiment of Foot (Highland Scots/Fraser's Highlanders)

- 4 Battalions of German Mercenaries

- North Carolina Royalist Battalion

- South Carolina Royalist Battalion

- New York Volunteers

- Artillery, commanded by Lieutenant Ralph Wilson

- Detachments from No. 1 Company, 4th Battalion, Royal Artillery

- No. 2 Company, 4th Battalion, Royal Artillery

- Detachments from No. 3 Company, 4th Battalion, Royal Artillery

- Detachments from No. 4 Company, 4th Battalion, Royal Artillery

- Detachments from No. 8 Company, 4th Battalion, Royal Artillery

Battle

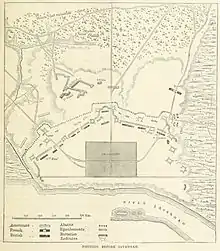

The place Campbell selected for landing was Girardeau's Plantation, located about 2 miles (3.2 km) below the city.[8][15] When word reached Howe that the landing had started on December 29, he sent a company of Continentals to occupy the bluffs above the landing site. Campbell realized that the bluffs would need to be controlled before the majority of his forces could land, and dispatched two companies of the 71st Regiment to take control of them. The Continentals opened fire at about 100 yards (91 m). The British, rather than returning fire, advanced rapidly with bayonets fixed, denying the Continentals a second shot. The Continentals retreated after they had killed four and wounded five at no cost to themselves. By noon, Campbell had landed his army and began to proceed cautiously toward the city.[16]

Howe held a council that morning and ground was chosen at which to make a stand. About one-half-mile (0.7 km) south of the city he established a line of defense in the shape of an open V, with the ends anchored by swampy woods. On the left, Howe placed Georgia Continentals and militia under Samuel Elbert, while on the right, he put South Carolina Continentals and militia under Isaac Huger and William Thomson. The line was supported by four pieces of field artillery, and light infantry companies guarded the flanks. Most of Howe's troops, including the Continentals, had seen little or no action in the war.[17]

When Campbell's advance companies spotted Howe's line around 2:00 pm, the main body stopped short of the field and Campbell went to see what he was up against. He viewed Howe's defenses as essentially sound, but a local slave told him that there was a path through the swamp on Howe's right.[18][19] Campbell ordered Sir James Baird to take 350 light infantry and 250 New York Loyalists and follow the slave through the swamp, while he arrayed his troops just out of view in a way that would give the impression he would attempt a flanking maneuver on Howe's left. One of his officers climbed a tree to observe Baird's progress. True to the slave's word, the trail came out near the Continental barracks, which had been left unguarded sice the Continentals were unaware they had been flanked. When they reached position, the man in the tree signaled by waving his hat, and Campbell ordered the regulars to charge.[20]

The first sounds of battle Howe heard were musket fire from the barracks, but these were rapidly followed by cannon fire and the appearance of charging British and German troops on his front. He ordered an immediate retreat, but it rapidly turned into a rout. His untried troops hardly bothered to return fire, some throwing down their weapons before attempting to run away through the swampy terrain. Campbell reported, "It was scarcely possible to come up with them, their retreat was rapid beyond Conception."[21] The light infantry in the Continental rear cut off the road to Augusta, the only significant escape route, which forced a mad scramble of retreating troops into the city itself. The Georgia soldiers on the right attempted to find a safe crossing of Musgrove Creek, but one did not exist, and many of the troops were taken prisoner.[22] Soldiers who did not immediately surrender were sometimes bayoneted. Colonel Huger managed to form a rear-guard to cover the escape of a number of the Continentals. Some of Howe's men managed to escape to the north before the British closed off the city, but others were forced to attempt swimming across Yamacraw Creek; an unknown number drowned in the attempt.[23]

Aftermath

Campbell gained control of the city at the cost to his forces of seven killed and seventeen wounded; including the four men killed and five wounded during preliminary skirmishing. Campbell took 453 prisoners, and there were at least 83 dead and 11 wounded from Howe's forces. The number of men who drowned during the retreat has been estimated at about 30.[24] When Howe's retreat ended at Purrysburg, South Carolina he had 342 men left, less than half his original army. Howe would receive much of the blame for the disaster, with William Moultrie arguing that he should have either disputed the landing site in force or retreated without battle to keep his army intact.[23] He was exonerated in a court martial that inquired into the event, but the tribunal pointed out that Howe should have made a stand at the bluffs or more directly opposed the landing.[25]

General Prevost arrived from East Florida in mid-January and soon sent Campbell with 1,000 men to take Augusta. Campbell occupied the frontier town against minimal opposition, but by then General Lincoln had begun to rally support in South Carolina to oppose the British.[26] Campbell abandoned Augusta on February 14, the same day a Loyalist force en route to meet him was defeated in the Battle of Kettle Creek. Although Patriot forces following the British were defeated at the March 3 Battle of Brier Creek, the Georgia backcountry remained in Patriot hands.[27]

Campbell wrote that he would be "the first British officer to [rend] a star and stripe from the flag of Congress."[23] Savannah was used as a base to conduct coastal raids which targeted areas from Charleston, South Carolina to the Florida coast. In the fall of 1779, a combined French and American siege to recapture Savannah failed and suffered significant casualties.[28] Control of Georgia was formally returned to its royal governor, James Wright, in July 1779,[29] but the backcountry would not come under British control until after the 1780 Siege of Charleston.[30] Patriot forces recovered Augusta by siege in 1781, but Savannah remained in British hands until 11 July 1782.[31]

Notes

- Wilson, p. 79

- Wilson, p. 80

- Heitman, pp. 670 and 681

- Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia. "U.S. National Archives: Founders Online: 'To George Washington from Major General Benjamin Lincoln, 5–6 January 1779': Explanatory notes: "The Battle, variously known as the Battle of Savannah and the Battle of Brewton Hill…"". U.S. National Archives. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- Morrill, p. 40

- Wilson, p. 61

- Wilson, p. 60

- Piecuch, p. 132

- Cashin, p. 73

- Wilson, p. 71

- Wilson, p. 67

- Wilson, p. 69

- Wilson, pp. 70–72

- Russell, p. 101

- Wilson, p. 72

- Wilson, pp. 73–74

- Russell, pp. 101–102

- Wison, p. 74

- Piecuch, p. 133

- Wilson, p. 75

- Wilson, p. 76

- Russell, p. 103

- Wilson, p. 77

- Ferling (2009), p. 325.

- Wilson, p. 78

- Russell, p. 104

- Russell, pp. 105–106

- "Revolutionary War in Georgia". Georgia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on September 19, 2008. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- Brooking, Greg (Winter 2014). "'Of Material Importance': Governor James Wright and the Siege of Savannah". Georgia Historical Quarterly. 98 (4). Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- Coleman, pp. 82–84

- Coleman, pp. 85–86

References

- Cashin, Edward (1999). The King's Ranger: Thomas Brown and the American Revolution on the Southern Frontier. New York: Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-1907-0. OCLC 246304277.

- Coleman, Kenneth (1991). A History of Georgia. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-1269-9. OCLC 21975722.

- Ferling, John (2009) [1977]. Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-1269-9. OCLC 21975722.

- Heitman, Francis B. (2000). Historical Register of the Officers of the Continental Army during the War of the Revolution: April, 1775, to December, 1783. Reprint of the New, Revised and Enlarged Edition of 1914. With Adenda by Robert H. Kelby, 1932. Baltimore: Clearfield. ISBN 0-8063-0176-7.

- Morrill, Dan (1993). Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution. Baltimore, MD: Nautical & Aviation Publishing. ISBN 978-0195382921.

- Piecuch, Jim (2008). Three peoples, one king : Loyalists, Indians, and Slaves in the Revolutionary South, 1775–1782. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-737-5. OCLC 185031351.

- Wilson, David K (2005). The Southern Strategy: Britain's Conquest of South Carolina and Georgia, 1775–1780. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-573-3. OCLC 232001108.

- Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia. "U.S. National Archives: Founders Online: 'To George Washington from Major General Benjamin Lincoln, 5–6 January 1779'". U.S. National Archives. Retrieved May 25, 2020.