Schinderhannes bartelsi

Schinderhannes bartelsi is a species of hurdiid radiodont (anomalocaridid) known from one specimen from the lower Devonian Hunsrück Slates. Its discovery was astonishing because previously, radiodonts were known only from exceptionally well-preserved fossil beds (Lagerstätten) from the Cambrian, 100 million years earlier.[1]

| Schinderhannes bartelsi Temporal range: Early Devonian | |

|---|---|

| |

| The holotype of Schinderhannes. Credit: Steinmann Institute/University of Bonn | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | †Dinocaridida |

| Order: | †Radiodonta |

| Family: | †Hurdiidae |

| Genus: | †Schinderhannes |

| Species: | †S. bartelsi |

| Binomial name | |

| †Schinderhannes bartelsi Kühl, Briggs & Rust, 2009 | |

Discovery

The single specimen was discovered in the Eschenbach-Bocksberg Quarry in Bundenbach, and is named after the outlaw Schinderhannes who frequented the area. Its specific epithet bartelsi honours Christoph Bartels, a Hunsrück Slate expert. The specimen is now housed in the Naturhistorisches Museum, Mainz.[1]

Morphology

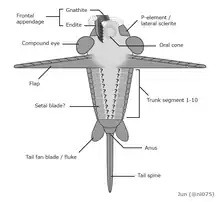

Schinderhannes is about 10 centimetres (3.9 in) long in full body length[1] (6.8cm long excluding telson[4]). Like other radiodonts, the head bears a pair of spiny frontal appendages, a radially-arranged ventral mouthpart (oral cone), and a pair of large lateral compound eyes.[1] Detailed morphology of the frontal appendages and oral cone are equivocal due to the limited preservation, but the former represent typical hurdiid features (e.g. subequal blade-like endites).[5][3] The eyes were in a relatively anterior position in contrast to other hurdiids.[3] There are traces of lateral structures originally thought to be the shaft regions of frontal appendages, which may rather represent P-elements (lateral sclerites) as seen in other radiodonts.[3] The boundary of head and trunk ('neck') was broad with a pair of long, ventrally-protruded flaps.[1] The trunk compose of 12 body segments indicated by soft dorsal cuticle[2] (originally thought to be rigid tergites[1]). The first 10 segments possess pairs of striated structures originally interpreted as biramous (branched) ventral flaps,[1] but later investigations from other radiodonts (e.g. Lyrarapax) suggest it may rather represent setal blades (dorsal gill-like structures of radiodont) and flap muscles.[2] The 11th segment bears another pair of shorter, rounded flaps.[1] The final segment lacking appendages and terminated with a long, spine-like telson.[1] A ventral anus located immediately before the telson.[4]

Ecology

The preserved contents of its digestive tract are typical of those of other predators',[6] and this lifestyle is supported by the raptorial nature of the spiny frontal appendages and the size of the eyes.[1] Schinderhannes may have been a swimmer (nekton), propelling itself with the long flaps attached to its head, and using its shorter flaps on the 11th segment to steer.[1] These flaps presumably derived from the lateral flaps of Cambrian radiodonts that used lobes along their sides to swim, but lacked the specializations as seen in Schinderhannes.[1]

Significance

As a Devonian radiodont, Schinderhannes's discovery was most significant because of the huge range extension of the radiodonts it caused: the group was only previously known from lagerstätten of the lower-to-middle Cambrian, 100 million years before. This underlined the utility of lagerstätten like the Hunsrück Slate: these exceptionally preserved fossil horizons may be the only available opportunity to observe non-mineralised forms.[7]

The discovery of Schinderhannes has also prompted novel hypothesis about the classification of basal arthropods. One classification scheme has Schinderhannes sister to the euarthropods (crown or 'true' arthropods) instead of other radiodonts, based on the characters which interpreted to be euarthropod-like (e.g. tergite, biramous appendage). This would mean that the euarthropod lineage evolved from a paraphyletic grade of radiodonts, and that the group of basal arthropods with 'great/frontal appendages' are not a natural grouping, and the biramous appendages of arthropods may then have arisen through fusion of radiodont lateral flaps and gills.[1] However, this scenario had been challenged by later investigations, as the putative euarthropod-like features were questioned to be rather radiodont-like characters (e.g. soft trunk cuticle, setal blades and paired flap muscles).[2] Phylogenetic analysis with focus on Radiodonta also repeatedly placed Schinderhannes within the radiodont family Hurdiidae.[8][9][10][4][3]

References

- Gabriele Kühl; Derek E. G. Briggs & Jes Rust (2009). "A great-appendage arthropod with a radial mouth from the Lower Devonian Hunsrück Slate, Germany". Science. 323 (5915): 771–773. Bibcode:2009Sci...323..771K. doi:10.1126/science.1166586. PMID 19197061. S2CID 47555807.

- Ortega-Hernández, Javier (2016). "Making sense of 'lower' and 'upper' stem-group Euarthropoda, with comments on the strict use of the name Arthropoda von Siebold, 1848: Upper and lower stem-Euarthropoda". Biological Reviews. 91 (1): 255–273. doi:10.1111/brv.12168. PMID 25528950. S2CID 7751936.

- Moysiuk, J.; Caron, J.-B. (2019-08-14). "A new hurdiid radiodont from the Burgess Shale evinces the exploitation of Cambrian infaunal food sources". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 286 (1908): 20191079. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.1079. PMC 6710600. PMID 31362637.

- Lerosey-Aubril, Rudy; Pates, Stephen (2018-09-14). "New suspension-feeding radiodont suggests evolution of microplanktivory in Cambrian macronekton". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 3774. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.3774L. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-06229-7. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6138677. PMID 30218075.

- Pates, Stephen; Daley, Allison C.; Butterfield, Nicholas J. (2019-06-11). "First report of paired ventral endites in a hurdiid radiodont". Zoological Letters. 5 (1): 18. doi:10.1186/s40851-019-0132-4. ISSN 2056-306X. PMC 6560863. PMID 31210962.

- Nicholas J. Butterfield (2002). "Leanchoilia, and the interpretation of three-dimensional structures in Burgess Shale-type fossils". Paleobiology. 28 (1): 155–171. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2002)028<0155:LGATIO>2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 3595514. S2CID 85606166.

- Nicholas J. Butterfield (1995). "Secular distribution of Burgess-Shale-type preservation". Lethaia. 28 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1995.tb01587.x.

- Vinther, Jakob; Stein, Martin; Longrich, Nicholas R.; Harper, David A. T. (2014). "A suspension-feeding anomalocarid from the Early Cambrian". Nature. 507 (7493): 496–499. Bibcode:2014Natur.507..496V. doi:10.1038/nature13010. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 24670770. S2CID 205237459.

- Cong, Peiyun; Ma, Xiaoya; Hou, Xianguang; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Strausfeld, Nicholas J. (2014). "Brain structure resolves the segmental affinity of anomalocaridid appendages". Nature. 513 (7519): 538–542. Bibcode:2014Natur.513..538C. doi:10.1038/nature13486. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 25043032. S2CID 4451239.

- Van Roy, Peter; Daley, Allison C.; Briggs, Derek E. G. (2015). "Anomalocaridid trunk limb homology revealed by a giant filter-feeder with paired flaps". Nature. 522 (7554): 77–80. Bibcode:2015Natur.522...77V. doi:10.1038/nature14256. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 25762145. S2CID 205242881.

External links

- Origin of claws seen in 390-million-year-old fossil

- Panda's Thumb: Schinderhannes bartelsi

- ScienceBlogs: Schinderhannes bartelsi, by PZ Myers showing a cladogram as proposed by G. Kühl et al., placing Schinderhannes (but not Anomalocaris) into the group of Euarthropoda.