School violence prevention through education

School violence prevention through education is the attempt to reduce violence and bullying through comprehensive approaches and interventions within the education sector. It aims to create a safe and non-violent learning environment. Acceptable practices include strong leadership; a safe and inclusive school environment; developing knowledge, attitudes, and skills; effective partnerships; implementing mechanisms for reporting and providing appropriate support and services, and collecting and using evidence.[1]

Background

School violence includes physical, psychological, and sexual violence and bullying and occurs in all countries. The root causes include gender and social norms and broader structural and contextual factors such as income inequality, deprivation, marginalization, and conflict. It is estimated that 246 million children and adolescents experience school violence in some form every year.[2]

Violence and bullying in schools violate the rights of children and adolescents, including their right to education and health. Studies show that school violence and bullying harm the academic performance, physical and mental health, and emotional well-being of those who are victimized.[2] It also has a detrimental effect on perpetrators and bystanders. An atmosphere of anxiety, fear, and insecurity that is incompatible with learning has a negative impact on the wider school environment.[2][3]

Education sector response

Different approaches can reduce violence and bullying and can also contribute to improving academic achievement and enhancing children’s social skills and well-being. UNESCO recommends that an effective and comprehensive education sector approach to school violence and bullying encompasses the following elements:[2]

- Leadership: developing and enforcing national laws and policies that protect children and adolescents from violence and bullying in schools; and allocating adequate resources to address school violence and bullying.

- School environment: creating safe and inclusive learning environments; strong school management; developing and enforcing school policies and codes of conduct, and ensuring that staff who violate these are held accountable.

- Capacity: training and support for teachers and other staff to ensure they have the knowledge and skills to use curriculum approaches that prevent violence and to respond to incidents of school violence and bullying; developing the capacity of children and adolescents; and developing appropriate knowledge, attitudes, and skills to prevent violence among children and adolescents.

- Partnerships: promoting awareness of the negative impact of school violence and bullying; collaboration with other sectors at the national and local level; partnerships with teachers and teachers’ unions; working with families and communities; and the active participation of children and adolescents.

- Services and support: providing accessible, child-sensitive, confidential reporting mechanisms; making available counseling and support; and referral to health and other services.

- Evidence: implementing comprehensive data collection; rigorous monitoring and evaluation to track progress and impact; and research to inform the design of programmes and interventions.[2]

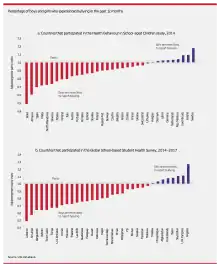

Changes in prevalence

According to studies, there was a decline in the prevalence of bullying in many countries, but fewer have seen a decrease in physical fights or physical attacks. Fewer than half of countries have seen a decrease in students in physical fighting. Of the 29 countries with trend data on involvement in a physical fight, 13 have seen a decrease, 12 have seen no change, and four have seen an increase. Physical attacks have decreased in half of the countries. Of 24 countries and territories with trend data on the prevalence of physical attacks, 12 have seen a decrease, 10 have seen no change and two have seen an increase in prevalence.[1][4]

Despite the prevalence of cyberbullying being low compared with other forms of school violence and bullying, it increases. In seven European countries, the proportion of children aged 11–16 years who use the Internet and reported that they had experienced cyberbullying increased from 7% in 2010 to 12% in 2014.[5]

Studies show that countries that have succeeded in reducing school violence and bullying or maintaining a low prevalence have nine factors in common. These key factors include:[1]

- Strong political leadership, a robust legal and policy framework, and consistent policies on violence against children, school violence and bullying, and related issues.

- Collaboration between the education sector and a wide range of partners at the national level, including non-education sector ministries, research institutions, and civil society organizations.

- Commitment to promoting a safe and positive school climate and classroom environment, including the use of positive discipline.

- Programmes and interventions based on research and evidence of effectiveness and impact on school violence and bullying.

- Strong commitment to child rights, empowerment and participation of children.

- Involvement and participation of stakeholders in the school community.

- Training and ongoing support for teachers.

- Mechanisms to provide support and referral to other services for students affected by school violence and bullying.

- Effective systems for reporting and monitoring school violence and bullying.[1]

See also

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO. Text taken from Behind the numbers: ending school violence and bullying, UNESCO. UNESCO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO. Text taken from Behind the numbers: ending school violence and bullying, UNESCO. UNESCO.

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO. Text taken from School violence and bullying: global status report, UNESCO. UNESCO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO. Text taken from School violence and bullying: global status report, UNESCO. UNESCO.

References

- UNESCO (2019). Behind the numbers: ending school violence and bullying. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100306-6.

- UNESCO (2017). School violence and bullying: global status report. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100197-0.

- Fry, Deborah, auteur. (18 May 2017). Child protection and disability : methodological and practical challenges for research. ISBN 978-1-78046-575-3. OCLC 1052491801.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Finkelhor, David; Ormrod, Richard K.; Turner, Heather A.; Hamby, Sherry L. (November 2005). "Measuring poly-victimization using the Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire". Child Abuse & Neglect. 29 (11): 1297–1312. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.06.005. ISSN 0145-2134. PMID 16274741.

- Mascheroni, G. and Cuman, A. 2014. Net children go mobile: Final report. Deliverables D6.4 & D5.2. Milano: Educatt.