Scientific socialism

Scientific socialism is a term which was coined in 1840 by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in his book What is Property?[1] to mean a society ruled by a scientific government, i.e., one whose sovereignty rests upon reason, rather than sheer will:[2]

Thus, in a given society, the authority of man over man is inversely proportional to the stage of intellectual development which that society has reached; and the probable duration of that authority can be calculated from the more or less general desire for a true government, — that is, for a scientific government. And just as the right of force and the right of artifice retreat before the steady advance of justice, and must finally be extinguished in equality, so the sovereignty of the will yields to the sovereignty of the reason, and must at last be lost in scientific socialism.

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

|

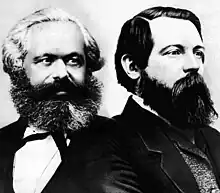

In the 1844 book The Holy Family, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels described the writings of the socialist, communist writers Théodore Dézamy and Jules Gay as truly "scientific".[3] Later in 1880, Engels used the term "scientific socialism" to describe Marx's social-political-economic theory.[4]

Although the term socialism has come to mean specifically a combination of political and economic science, it is also applicable to a broader area of science encompassing what is now considered sociology and the humanities. The distinction between Utopian and scientific socialism originated with Marx, who criticized the Utopian characteristics of French socialism and English and Scottish political economy. Engels later argued that Utopian socialists failed to recognize why it was that socialism arose in the historical context that it did, that it arose as a response to new social contradictions of a new mode of production, i.e. capitalism. In recognizing the nature of socialism as the resolution of this contradiction and applying a thorough scientific understanding of capitalism, Engels asserted that socialism had broken free from a primitive state and become a science.[4]

This shift in socialism was seen as complementary to shifts in contemporary biology sparked by Charles Darwin and the understanding of evolution by natural selection—Marx and Engels saw this new understanding of biology as essential to the new understanding of socialism and vice versa.

Examples

In Bangladesh after 1971, Jatiya Samajtantrik Dal was formed with an aim to exercise rule based on scientific socialism.[5][6]

In Japan, the Japanese Communist Party has an ideology based on scientific socialism.[7]

Methodology

Scientific socialism refers to a method for understanding and predicting social, economic and material phenomena by examining their historical trends through the use of the scientific method in order to derive probable outcomes and probable future developments. It is in contrast to what later socialists referred to as utopian socialism—a method based on establishing seemingly rational propositions for organizing society and convincing others of their rationality and/or desirability. It also contrasts with classical liberal notions of natural law, which are grounded in metaphysical notions of morality rather than a dynamic materialist or physicalist conception of the world.[8]

Scientific socialists view social and political developments as being largely determined by economic conditions, in contrast to the ideas of Utopian socialists and classical liberals, and thus believe that social relations and notions of morality are context-based relative to their specific stage of economic development. They believe that as economic systems, socialism and capitalism are not social constructs that can be established at any time based on the subjective will and desires of the population, but instead are the products of social evolution. An example of this was the advent of agriculture which enabled human communities to produce a surplus—this change in material and economic development led to a change in the social relations and rendered the old form of social organization based on subsistence-living obsolete and a hindrance to further material progress. The changing economic conditions necessitated a change in social organization.[4]

See also

- Anti-Duhring

- Critique of Dialectical Reason – 1960 book by Jean-Paul Sartre

- El Defensor del Obrero

- Evolutionary economics – A field in economics that considers economic evolution

- GOELRO, an early Soviet national plan for economic recovery which emphasised the importance of electrification

- Historical materialism – Marxist historiography

- Project Cybersyn, a decentralized form of cybernetic planning in Chile that was operational from 1971 until 1973.

- OGAS, a proposed national computer network for economic planning in the Soviet Union.

- Social science, one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among individuals within those societies.

- Socialism with Chinese characteristics, the official ideology of the Chinese Communist Party

- Scientific Outlook on Development, a socio-economic concept of the Chinese Communist Party

- Scientific communism, the Soviet Union curriculum requirements for understanding Soviet orthodoxy on the subject.

- Science and technology in the Soviet Union

- Siad Barre, who called his mixture of Marxism-Leninism and Islam "scientific socialism".

- Socialism: Utopian and Scientific

- Socialist mode of production

- The Open Society and Its Enemies – 1945 book by Karl Popper

- Why Socialism? - an article written by Albert Einstein which presented a critique of modern capitalism and advocated for a planned economy.

References

- Peddle, Francis K.; Peirce, William S. (2022-01-15). The Annotated Works of Henry George: The Science of Political Economy. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 269. ISBN 978-1-68393-339-7. Archived from the original on 2023-07-01. Retrieved 2022-01-16.

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph (1994). Proudhon: What is Property?. Cambridge University Press. p. 208. ISBN 9780521405560. Archived from the original on 2023-07-01. Retrieved 2021-12-04.

- Marx, K., and F. Engels, The Holy Family:Critique of Critical Criticism. Ch. VI 3. Online at: http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/holy-family/ch06_3_d.htm Archived 2021-05-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- Engels, Friedrich (1880). Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Ahmed Sofa (23 March 2015). "Jatia Samajtantrik Dal: A Sentimental Appraisal". Foreign Affairs Insights & Review. Retrieved 2022-07-10.

- Mitra, Subrata Kumar; Siegfried O. Wolf; Jivanta Schöttli (2006). A political and economic dictionary of South Asia. London. pp. 195–196. ISBN 978-0-203-40326-6. OCLC 912319314.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "How the Japanese Communist Party Developed its Theory of Scientific Socialism - jcpcc". www.jcp.or.jp. Archived from the original on 2021-12-09. Retrieved 2023-04-01.

- Ferri, Enrico (1912). Socialism and Modern Science. From "Evolution and Socialism" (p. 79): "Upon what point are orthodox political economy and socialism in absolute conflict? Political economy has held and holds that the economic laws governing the production and distribution of wealth which it has established are natural laws ... not in the sense that they are laws naturally determined by the condition of the social organism (which would be correct), but that they are absolute laws, that is to say, that they apply to humanity at all times and in all places, and consequently, that they are immutable in their principal points, though they may be subject to modification in details. Scientific socialism holds, on the contrary, that the laws established by classical political economy, since the time of Adam Smith, are laws peculiar to the present period in the history of civilized humanity, and that they are, consequently, laws essentially relative to the period of their analysis and discovery".