Scincosaurus

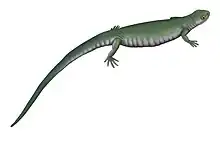

Scincosaurus is an extinct genus of nectridean lepospondyl within the family Scincosauridae.[1]

| Scincosaurus Temporal range: Late Carboniferous, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subclass: | †Lepospondyli |

| Order: | †Nectridea |

| Family: | †Scincosauridae |

| Genus: | †Scincosaurus Frič, 1876 |

| Type species | |

| †Scincosaurus crassus Frič, 1876 | |

| Species | |

|

†S. crassus Frič, 1876 | |

History

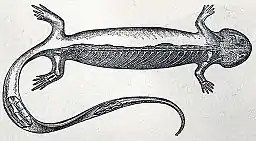

Scincosaurus crassus was first described by Bohemian paleontologist Antonín Frič in volume 1875 of "Sitzungsberichte der königlichen Böhmischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften in Prague", which at that time was the premiere scientific journal of Bohemia (the modern day Czech Republic). Frič's contribution to this volume was a list of Carboniferous animals he and his associates recently discovered at coal gas mines near the localities of Nýřany and Kounová. His list included short preliminary descriptions for many new genera and species of tetrapods, including Microbrachis, Branchiosaurus, Hyloplesion (at that time called Stelliosaurus), and Sparodus. Scincosaurus crassus was among the new tetrapods from Nýřany, and its short description (erroneously) considered it a robust lacertilian (lizard), possibly related to Sparodus.[2]

A much larger description was published in 1881 as part of one of Frič's personal monographs which focused entirely on the paleontology of Bohemia. Within this monograph, Frič identified Scincosaurus crassus as a nectridean and provided a comprehensive overview of the taxa's anatomy. He noticed a pair of prong-like bones near the back of the skull of one specimen, which he was convinced were examples of tabular horns. These horns, which form from the tabular bones at the rear of the skull, are characteristic of diplocaulids, and as a result Frič renamed Scincosaurus crassus to Keraterpeton crassum, a new species of the basal diplocaulid Keraterpeton.[3]

In 1895, the idea that Scincosaurus crassus was simply a species of Keraterpeton was reevaluated and subsequently refuted. While studying a specimen of Keraterpeton galvani (the type species of Keraterpeton), British paleontologist C.W. Andrews noticed that there were many differences between skulls of that species and Keraterpeton crassum (a.k.a. Scincosaurus crassus). K. galvani had fairly large eyes positioned close to each other on the skull, while K. crassum had small and widely separated eyes. The skull of K. crassum was more heavily sculptured by pits and grooves and did not possess a significant overhang of the braincase, in contrast to K. galvani. The purported tabular horns were seemingly separated from the rest of the skull by means of a ball-and-socket joint, while no such delineation existed for K. galvani, whose horns were simply rear branches of the tabular bones. As a result, he resurrected the genus Scincosaurus for "Keraterpeton" crassum, although he retained the misspelled specific name, "crassum".[4] Subsequent authors would correct this error by referring to the species as Scincosaurus crassus as Frič originally did in 1876. In 1903, German paleontologist Otto Jaekel noted that he could not find any evidence of the supposed jointed tabular horns on any Scincosaurus specimens. He supposed that Frič may have erroneously mistaken bones of the shoulder girdle (such as a scapula, or shoulder blade) for the horns.[5]

In 1909, Jaekel placed Scincosaurus within its own family, Scincosauridae. However, he did not consider scincosaurs to be part of Nectridea, which to him was restricted to the horned diplocaulids. Instead, scincosaurids were allied with the long-tailed urocordylids and snake-like ophiderpetontids in an order he called Urosauri. Urosaurs, nectrideans, and several other groups of early tetrapods were all considered to belong to the class Microsauria. Microsauria was kept separate from traditional linnean classes such as Reptilia, Mammalia, and Amphibia, due to paleontologists of the time being generally uncertain whether they were reptile-like amphibians or amphibian-like reptiles.[6] Following Jaekel's hypothesis, Robert Broom used Scincosaurus as a representative of microsaurs during his 1921 study on tetrapod ankle bones.[7]

As the 20th century proceeded, Scincosaurus fell into obscurity. However, by the 1960s sources which did discuss it once again considering it a member of Nectridea outside of Microsauria. During his 1963 monograph on the advanced diplocaulid Diploceraspis, J.R. Beerbower placed Scincosaurus as a basal diplocaulid closely related to Batrachiderpeton in a subfamily he called Batrachiderpetoninae.[8] Even so, Scincosaurus was still distantly related to microsaurs, as a growing body of evidence suggested that microsaurs were not reptiles, but relatives of the nectrideans within a subgroup of amphibians called Lepospondyli.[9][10]

In 1982, a second species of Scincosaurus was named by C. Civet: Scincosaurus spinosus. This species, which was found in Carboniferous deposits near Montceau-les-Mines in France, is well-preserved yet poorly described.[11] During their description of the urocordylid Montcellia in 1994, Jean-Michel Dutuit and D. Heyler considered that S. spinosus may not belong to Scincosaurus, but rather its French close relative Sauravus.[12] Phylogenetic studies on nectrideans conducted by Andrew Milner, Angela Milner, and Marcello Ruta have consistently found Scincosaurus to be a member of the order since 1978. One of these studies, Milner & Ruta (2009), included a large redescription and reinterpretation of Scincosaurus crassus.[1]

References

- Milner, Angela C.; Ruta, Marcello (2009). "A revision of Scincosaurus (Tetrapoda, Nectridea) from the Moscovian of Nýřany, Czech Republic, and the phylogeny and interrelationships of nectrideans". Special Papers in Palaeontology. 81: 71–90.

- Frič, Antonin (March 19, 1876). "Uber die Fauna der Gaskohle des Pilsner und Rakonitzer Beckens". Sitzungsberichte der königlichen böhmischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften in Prague. 1875: 70–78.

- Frič, Antonin (1881). "Fauna der Gaskohle und der Kalksteine der Permformation Böhmens". Self-published. Prague. 1 (3): 136–146.

- Andrews, C.W. (1895). "Notes on a specimen of Keraterpeton galvani, Huxley, from Staffordshire". Geological Magazine. 2 (2): 81–84. doi:10.1017/S0016756800005847. S2CID 129872725.

- Jaekel, Otto (1903). "Über Ceraterpeton, Diceratosaurus und Diplocaulus". Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geognosie, Geologie und Petrefaktenkunde. 1: 109–134.

- Jaekel, Otto (1909). "Über die Klassen der Tetrapoden". Zoologischer Anzeiger. 34: 193–212.

- Broom, R. (February 22, 1921). "On the structure of the reptilian tarsus". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 1921 (1–2): 143–155. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1921.tb03253.x.

- Beerbower, J.R. (November 1963). "Morphology, paleoecology, and phylogeny of the Permo-Pennsylvania amphibian Diploceraspis". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. 130 (2): 31–108.

- Baird, Donald (May 1965). "Paleozoic lepospondyl amphibians". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 5 (2): 287–294.

- Carroll, Robert L.; Baird, Donald (August 9, 1968). "The Carboniferous Amphibian Tuditanus [Eosauravus] and the Distinction Between Microsaurs and Reptiles" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (2337): 1–47.

- Civet, C. (1982). "Étude d'un nouvel Amphibien Fosile du Basin Houiller de Montceau-les-Mines Scincosuarus spinosus nov. sp". La Physiophile. Société d'Études des Sciences Naturelles et Historigues de Montceau-les-Mines. 96: 73–79.

- Dutuit, Jean-Michel; Heyler, D. (1994). "Rachitomes, Lépospondyles et Reptiles due Stephanien (Carbonifere superieur) du basin de Montceau-les-Mines (Massif central, France)". Mémoires de la section des Sciences. 12: 249–266.