Scipione

Scipione (HWV 20), also called Publio Cornelio Scipione, is an opera seria in three acts, with music composed by George Frideric Handel for the Royal Academy of Music in 1726. The librettist was Paolo Antonio Rolli. Handel composed Scipione whilst in the middle of writing Alessandro. It is based on the life of the Roman general Scipio Africanus. Its slow march is the regimental march of the Grenadier Guards and is known for being played at London Metropolitan Police passing out ceremonies.

Performance history

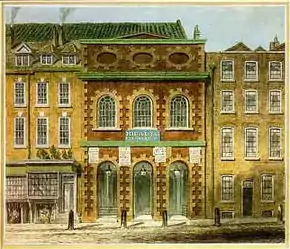

Scipione had its premiere on 12 March 1726 at The King's Theatre, Haymarket. Handel revived the opera in 1730, but it did not receive another UK production until October 1967, by the Handel Opera Society. In Germany, Scipione was revived at the Göttingen International Handel Festival in 1937 and at the annual Handel Festival in Halle in 1965.[1] With the revival of interest in Baroque music and historically informed musical performance since the 1960s, Scipione, like all Handel operas, receives performances at festivals and opera houses today.[2]

Roles

| Role[3] | Voice type | Premiere cast, 12 March 1726 |

|---|---|---|

| Scipione, commander of the Roman army | alto castrato | Antonio Baldi |

| Lucejo, Spanish prince, in disguise in the Roman army | alto castrato | Francesco Bernardi, called "Senesino" |

| Lelio, Roman general | tenor | Luigi Antinori |

| Berenice, prisoner | soprano | Francesca Cuzzoni |

| Armira, prisoner | soprano | Livia Constantini |

| Ernando, King of the Balearic Islands and father to Berenice | bass | Giuseppe Maria Boschi |

Prologue

The setting is New Carthage (Cartagena), 210 BCE, after the Roman army, led by Scipione has captured the city from the Carthaginians and their Spanish allies.

Act 1

Scipione leads a procession of captives into the city through the triumphal arch. He anticipates future conquests and salutes his officers, with a particular laurel for Lelio. Lelio, in return, offers the prisoner Berenice to Scipione. Scipione is immediately attracted to Berenice, but vows to respect her honour. Berenice is in love with the Spanish prince Lucejo, who is among the Roman army incognito. He vows to rescue her. Lelio himself is attracted to another prisoner, Armira, but she will not return the affection whilst a prisoner. This begins to draw Lelio in sympathy with the female prisoners, although he does advise Berenice to accept Scipione's affection.

The female prisoners are confined in a palace with a garden, but Scipione has forbidden strangers to enter. Still disguised, Lucejo breaches the garden, but hides when he hears Scipione approaching. Scipione tries to win over Berenice and proclaims his love for her. Lucejo cannot tolerate this, and betrays his presence by his exclamation. Berenice tries to protect Lucejo by calling him a madman and begging for mercy. Alone at the end of the act, Lucejo is unsure of Berenice's motives and begins to become jealous.

Act 2

Ernando, father to Berenice, has arrived to offer a ransom for his daughter and also friendship to Scipione. Scipione tries again to woo Berenice, but she again rejects his advances. After Scipione has left, Lucejo reappears, but she dismisses him. This confirms Lucejo's initial jealous suspicions, but Berenice feels emotionally torn. Even with his jealous feelings, Lucejo does not completely break with Berenice, but he does pretend to express affection for Armira, in the expectation that Berenice will overhear this. Both Berenice and Armira are distressed at the situation, and Scipione arrives, angry to see Lucejo in the garden. Lucejo now confesses his identity and his plans, and challenges Scipione to a duel. Scipione orders the arrest of Lucejo. Berenice then admits that she could love a Roman, if she had not promised herself to another.

Act 3

Scipione offers Ernando freedom for Berenice, on condition that he may marry her. Ernando replies that he would willingly give up his life and kingdom, but that he cannot break his earlier promise to Lucejo of Berenice in marriage. This nobility impresses Scipione, who then plans to send Lucejo to Rome as a prisoner. He further ponders the situation, and resolves to sacrifice his own personal desires for the greater happiness of the others. He tells Berenice of his change of mind and heart. He accepts the ransom offer from Ernando and frees Berenice, saying that she may marry Lucejo. Furthermore, he gives the ransom to the couple as a wedding present. All present praise Scipione's generosity, and Lucejo vows loyalty to Rome for himself and his subjects.[4]

Context and analysis

The German-born Handel, after spending some of his early career composing operas and other pieces in Italy, settled in London, where in 1711 he had brought Italian opera for the first time with his opera Rinaldo. A tremendous success, Rinaldo created a craze in London for Italian opera seria, a form focused overwhelmingly on solo arias for the star virtuoso singers. In 1719, Handel was appointed music director of an organisation called the Royal Academy of Music (unconnected with the present day London conservatoire), a company under royal charter to produce Italian operas in London. Handel was not only to compose operas for the company but hire the star singers, supervise the orchestra and musicians, and adapt operas from Italy for London performance.[5][6]

Within the year 1724–1725, Handel wrote three great operas in succession for the Royal Academy of Music, each with Senesino and Francesca Cuzzoni as the stars, Giulio Cesare,Tamerlano, and Rodelinda.[4]

The directors of the Royal Academy of Music decided to increase the appeal of the operas by bringing another internationally famous singer, the soprano Faustina Bordoni, to join the established London stars Cuzzoni and Senesino, as was reported in the London press - the Daily Journal wrote on 31 August 1725

'We hear that the Royal Academy (of) Musick, in the Hay Market, have contracted with famous Chauntess for 2500 l. who is coming over from Italy against the Winter'[4] with the London Journal adding "'Signiora Faustina, a famous Italian Lady, is coming over this Winter to rival Signiora Cuzzoni".[4]

However Faustina did not arrive when expected, which meant that the opera Handel was composing to feature two equally important leading ladies, Alessandro, was not suitable for the gap in the opera house's schedule which had to be filled. For this reason he composed Scipione in three weeks and it received its first performance ten days after he finished composing it.[4]

The haste in which Scipione was put together perhaps shows in the finished work, although it was successful with London audiences and contains much beautiful music, as 18th century musicologist Charles Burney wrote:

though the first act of this opera is rather feeble, and the last not so excellent as that of some of his other dramas, the second act contains beauties of various kinds sufficient to establish its reputation, as a work worthy of its great author in his meridian splendor.[7]

Ellen Harris has discussed Handel's specific use of musical keys in the opera, noting, for example, that the opera starts and concludes in G major.[8] Winton Dean has noted that the opera originally contained the character of Rosalba, mother to Berenice. However, because the singer originally scheduled for the role of Rosalba was not available, that role was removed and the music and text transferred to other characters. In addition, Dean has commented on dramatic weaknesses in the plot of act 3.[1]

The opera is scored for two recorders, two flutes, two oboes, bassoon, two horns, strings, and continuo instruments (cello, lute, harpsichord).

Recordings

- Complete recording conducted by Christophe Rousset. Les Talens Lyriques. 3CDs FNAC 1994, reissue Aparté/Ambroisie 2010. Scipione: Derek Lee Ragin; Berenice: Sandrine Piau; Lucejo: Doris Lamprecht, mezzo-soprano; Ernando: Olivier Lallouette, baritone; Armira: Vanda Tabery, soprano; Lelio: Guy Fletcher, tenor.

References

Notes

- Dean, Winton, "Handel's Scipione (October 1967). The Musical Times, 108 (1496): pp. 902–904.

- "Handel:A Biographical Introduction". GF Handel.org. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- "G. F. Handel's Compositions". GF Handel.org. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- "Scipione". handelhendrix.org. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- Dean, W. & J.M. Knapp (1995) Handel's operas 1704-1726, p. 298.

- Strohm, Reinhard (20 June 1985). Essays on Handel and Italian opera by Reinhard Strohm. ISBN 9780521264280. Retrieved 2 February 2013 – via Google Books.

- Charles Burney: A General History of Music: from the Earliest Ages to the Present Period. Vol. 4, London 1789, reprint: Cambridge University Press 2010, ISBN 978-1-1080-1642-1, p. 306.

- Harris, Ellen T., "The Italian in Handel" (Autumn 1980). Journal of the American Musicological Society, 33 (3): pp. 468–500.

Sources

- Dean, Winton; Knapp, J. Merrill (1987), Handel's Operas, 1704–1726, Clarendon Press, ISBN 0193152193 The first of the two-volume definitive reference on the operas of Handel

External links

- Italian libretto

- Score of Scipione (ed. Friedrich Chrysander, Leipzig 1877)

- Scipione: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project