Submarine earthquake

A submarine, undersea, or underwater earthquake is an earthquake that occurs underwater at the bottom of a body of water, especially an ocean. They are the leading cause of tsunamis. The magnitude can be measured scientifically by the use of the moment magnitude scale and the intensity can be assigned using the Mercalli intensity scale.

| Part of a series on |

| Earthquakes |

|---|

|

|

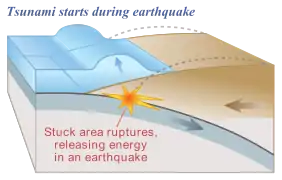

Understanding plate tectonics helps to explain the cause of submarine earthquakes. The Earth's surface or lithosphere comprises tectonic plates which average approximately 50 miles in thickness, and are continuously moving very slowly upon a bed of magma in the asthenosphere and inner mantle. The plates converge upon one another, and one subducts below the other, or, where there is only shear stress, move horizontally past each other (see transform plate boundary below). Little movements called fault creep are minor and not measurable. The plates meet with each other, and if rough spots cause the movement to stop at the edges, the motion of the plates continue. When the rough spots can no longer hold, the sudden release of the built-up motion releases, and the sudden movement under the sea floor causes a submarine earthquake. This area of slippage both horizontally and vertically is called the epicenter, and has the highest magnitude, and causes the greatest damage.

As with a continental earthquake the severity of the damage is not often caused by the earthquake at the rift zone, but rather by events which are triggered by the earthquake. Where a continental earthquake will cause damage and loss of life on land from fires, damaged structures, and flying objects; a submarine earthquake alters the seabed, resulting in a series of waves, and depending on the length and magnitude of the earthquake, tsunami, which bear down on coastal cities causing property damage and loss of life.

Submarine earthquakes can also damage submarine communications cables, leading to widespread disruption of the Internet and international telephone network in those areas. This is particularly common in Asia, where many submarine links cross submarine earthquake zones along Pacific Ring of Fire.

Tectonic plate boundaries

The different ways in which tectonic plates rub against each other under the ocean or sea floor to create submarine earthquakes. The type of friction created may be due to the characteristic of the geologic fault or the plate boundary as follows. Some of the main areas of large tsunami producing submarine earthquakes are the Pacific Ring of Fire and the Great Sumatran fault.

Convergent plate boundary

The older, and denser plate moves below the lighter plate. The further down it moves, the hotter it becomes, until finally melting altogether at the asthenosphere and inner mantle and the crust is actually destroyed. The location where the two oceanic plates actually meet become deeper and deeper creating trenches with each successive action. There is an interplay of various densities of lithosphere rock, asthenosphere magma, cooling ocean water and plate movement for example the Pacific Ring of Fire. Therefore, the site of the sub oceanic trench will be a site of submarine earthquakes; for example the Mariana Trench, Puerto Rico Trench, and the volcanic arc along the Great Sumatran fault.[1]

Transform plate boundary

A transform-fault boundary, or simply a transform boundary is where two plates will slide past each other, and the irregular pattern of their edges may catch on each other. The lithosphere is neither added to from the asthenosphere nor is it destroyed as in convergent plate action. For example, along the San Andreas fault strike-slip fault zone, the Pacific Tectonic Plate has been moving along at about 5 cm/yr in a northwesterly direction, whereas the North American Plate is moving south-easterly.[2]

Divergent plate boundary

Rising convection currents occur where two plates are moving away from each other. In the gap, thus produced hot magma rises up, meets the cooler sea water, cools, and solidifies, attaching to either or both tectonic plate edges creating an oceanic spreading ridge. When the fissure again appears, again magma will rise up, and form new lithosphere crust. If the weakness between the two plates allows the heat and pressure of the asthenosphere to build over a large amount of time, a large quantity of magma will be released pushing up on the plate edges and the magma will solidify under the newly raised plate edges, see formation of a submarine volcano. If the fissure is able to come apart because of the two plates moving apart, in a sudden movement, an earthquake tremor may be felt for example at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Africa.[3]

List of major submarine earthquakes

The following is a list of some major submarine earthquakes since the 17th century.

| Date | Event | Location | Estimated moment magnitude (Mw) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 11, 2011 | 2011 Tōhoku earthquake | The epicenter is 130 kilometers (81 mi) off the east coast of the Oshika Peninsula, Tōhoku, with the hypocenter at a depth of 32 km (20 mi). | 9.0 | This is the largest known earthquake to hit Japan |

| December 26, 2006 | 2006 Hengchun earthquakes | The epicenter is off the southwest coast of Taiwan, in the Luzon Strait, which connects the South China Sea with the Philippine Sea. | 7.1 | |

| December 26, 2004 | 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake | The epicenter is off the northwestern coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. | 9.1 | This is the third largest earthquake in recorded history and generated massive tsunamis, which caused widespread devastation when they hit land, leaving an estimated 230,000 people dead in countries around the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean. |

| May 4, 1998 | A part of the island of Yonaguni was destroyed by a submarine earthquake. | |||

| May 22, 1960 | 1960 Valdivia earthquake | The epicenter is off the coast of South Central Chile. | 9.5 | This is the largest earthquake ever recorded. |

| December 20, 1946 | 1946 Nankai earthquake | The epicenter is off the southern coast of Kii Peninsula and Shikoku, Japan. | 8.1 | |

| December 7, 1944 | 1944 Tōnankai earthquake | The epicenter is about 20 km off the coast of the Shima Peninsula in Japan. | 8.0 | |

| November 18, 1929 | 1929 Grand Banks earthquake | The epicenter is at Grand Banks, off the south coast of Newfoundland in the Atlantic Ocean. | 7.2 | |

| June 15, 1896 | 1896 Sanriku earthquake | The epicenter is off the Sanriku coast of northeastern Honshū, Japan. | 8.5 | |

| April 4, 1771 | The epicenter is near Yaeyama Islands in Okinawa, Japan. | 7.4 | ||

| January 26, 1700 | 1700 Cascadia earthquake | The epicenter is offshore from Vancouver Island to northern California. | ~9.0 | This is one of the largest earthquakes on record. |

Storm-caused earthquakes

A 2019 study based on new higher-resolution data from the Transportable Array network of USArray found that large ocean storms could create undersea earthquakes when they passed over certain areas of the ocean floor, including Georges Bank near Cape Cod and the Grand Banks of Newfoundland.[4] They have also been observed in the Pacific Northwest.[5]

See also

References

- Convergent Plate Boundaries - Convergent Boundary - Geology.com Archived 2007-05-01 at the Wayback Machine URL accessed January 23, 2007

- Understanding plate motions [This Dynamic Earth, USGS, Archived 2019-05-16 at the Wayback Machine, URL accessed January 23, 2007

- Divergent Plate Boundaries - Divergent Boundary - Geology.com Archived 2007-05-01 at the Wayback Machine URL accessed January 23, 2007

- "Stormquakes! They're real — and happening off New England". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 2019-10-28. Retrieved 2019-10-27.

- "Short Wave - Discovering 'Stormquakes'". NPR.org. 2020-01-29. Archived from the original on 2021-04-19. Retrieved 2021-04-15.