Second-rate

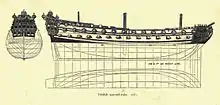

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a second-rate was a ship of the line which by the start of the 18th century mounted 90 to 98 guns on three gun decks; earlier 17th-century second rates had fewer guns and were originally two-deckers or had only partially armed third gun decks. A "second rate" was the second largest class of warships in a hierarchical system of six "ratings" based on size and firepower.

They were essentially smaller and hence cheaper versions of the three-decker first rates. Like the first rates, they fought in the line of battle, but unlike the first rates, which were considered too valuable to risk in distant stations, the second rates often served also in major overseas stations as flagships. They had a reputation for poor handling and slow sailing. They were popular as flagships of admirals commanding the Windward and/or Leeward Islands station, which was usually a Rear-admiral of the red.

Rating

Typically measuring around 2000 tons burthen and carrying a crew of 750, the second-rates by the second half of the 18th century carried 32-pounder guns on the gun deck, with 18-pounders instead of 24-pounders on the middle deck, and 12-pounders on the upper deck (rather than 18- or 24-pounders on first rates), although there were exceptions to this. Both first and second rates carried lighter guns (and, after 1780, carronades) on their forecastles and quarterdecks.

Three-decker v two-decker

The three-decker second-rate was mainly a British type, and was not built by other European navies to any great degree.[1] As speed is mainly determined by length along the waterline, the three-deck, second-rate was a slow sailer compared to both its two-deck equivalent and the first-rate ships.[2] Being the same height as a first-rate but shorter meant they handled poorly and had a tendency to sail to leeward; HMS Prince was described by one of her lieutenants as sailing "like a haystack".[3] Their poor sailing abilities prompted Nelson, at Trafalgar, to order Prince and HMS Dreadnought to approach the enemy at a lesser angle than the remainder of the column, in the hope that having more sail area exposed to the wind, would enable these two ships to keep up. A near disastrous example of the three-decker's maladroitness occurred on 25 December 1796 when, on sighting the enemy, the Channel Fleet attempted a hurried departure from Spithead: Four second-rates collided with each other while another ran aground.[4]

Apart from its unhandiness, in terms of sheer firepower it was matched or even out-gunned by many of the large 80-gun and 74-gun two-deckers used by the French and Spanish navies.[1] The additional height did, however, give the second rate an advantage in close combat with the further advantage of it being able to withstand punishment like a larger ship, but being much cheaper to build and maintain. It was sometimes mistaken by the enemy for a first-rate, which could possibly make enemy commanders reluctant to press an attack.

After the Napoleonic wars, new second rates in the Royal Navy mounted their guns (typically 90 or 91) on two decks once more, leaving the first rates as the only ships with three complete gun decks.

Term

The term "second-rate" has since passed into general usage as an adjective used to mean of suboptimal quality, inferior to something that is "first-rate".

Bibliography

- Bennett, G. The Battle of Trafalgar, Barnsley (2004). ISBN 1-84415-107-7.

- Gardiner, Robert (2004). Warships of the Napoleonic Era: Design, Development and Deployment. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-108-3.

- Rodger, N. A. M. The Command of the Ocean, a Naval History of Britain 1649–1815, London (2004). ISBN 0-7139-9411-8.

- Winfield, Rif, British Warships in the Age of Sail: 1603–1714, Barnsley (2009) ISBN 978-1-84832-040-6; British Warships in the Age of Sail: 1714–1792, Barnsley (2007) ISBN 978-1-84415-700-6; British Warships in the Age of Sail: 1793–1817, (2nd edition) Barnsley (2008). ISBN 978-1-84415-717-4; British Warships in the Age of Sail: 1817–1863, Barnsley (2014) ISBN 978-1-84832-169-4.

Citations

- Gardiner p. 14

- Gardiner p. 18

- Gardiner pp. 14–15

- Gardiner p. 15