Segregation (materials science)

In materials science, segregation is the enrichment of atoms, ions, or molecules at a microscopic region in a materials system. While the terms segregation and adsorption are essentially synonymous, in practice, segregation is often used to describe the partitioning of molecular constituents to defects from solid solutions,[1] whereas adsorption is generally used to describe such partitioning from liquids and gases to surfaces. The molecular-level segregation discussed in this article is distinct from other types of materials phenomena that are often called segregation, such as particle segregation in granular materials, and phase separation or precipitation, wherein molecules are segregated in to macroscopic regions of different compositions. Segregation has many practical consequences, ranging from the formation of soap bubbles, to microstructural engineering in materials science,[2] to the stabilization of colloidal suspensions.

Segregation can occur in various materials classes. In polycrystalline solids, segregation occurs at defects, such as dislocations, grain boundaries, stacking faults, or the interface between two phases. In liquid solutions, chemical gradients exist near second phases and surfaces due to combinations of chemical and electrical effects.

Segregation which occurs in well-equilibrated systems due to the instrinsic chemical properties of the system is termed equilibrium segregation. Segregation that occurs due to the processing history of the sample (but that would disappear at long times) is termed non-equilibrium segregation.

History

Equilibrium segregation is associated with the lattice disorder at interfaces, where there are sites of energy different from those within the lattice at which the solute atoms can deposit themselves. The equilibrium segregation is so termed because the solute atoms segregate themselves to the interface or surface in accordance with the statistics of thermodynamics in order to minimize the overall free energy of the system. This sort of partitioning of solute atoms between the grain boundary and the lattice was predicted by McLean in 1957.[3]

Non-equilibrium segregation, first theorized by Westbrook in 1964,[4] occurs as a result of solutes coupling to vacancies which are moving to grain boundary sources or sinks during quenching or application of stress. It can also occur as a result of solute pile-up at a moving interface.[5]

There are two main features of non-equilibrium segregation, by which it is most easily distinguished from equilibrium segregation. In the non-equilibrium effect, the magnitude of the segregation increases with increasing temperature and the alloy can be homogenized without further quenching because its lowest energy state corresponds to a uniform solute distribution. In contrast, the equilibrium segregated state, by definition, is the lowest energy state in a system that exhibits equilibrium segregation, and the extent of the segregation effect decreases with increasing temperature. The details of non-equilibrium segregation are not going to be discussed here, but can be found in the review by Harries and Marwick.[6]

Importance

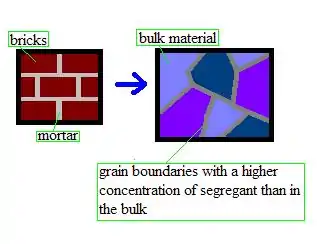

Segregation of a solute to surfaces and grain boundaries in a solid produces a section of material with a discrete composition and its own set of properties that can have important (and often deleterious) effects on the overall properties of the material. These 'zones' with an increased concentration of solute can be thought of as the cement between the bricks of a building. The structural integrity of the building depends not only on the material properties of the brick, but also greatly on the properties of the long lines of mortar in between.

Segregation to grain boundaries, for example, can lead to grain boundary fracture as a result of temper brittleness, creep embrittlement, stress relief cracking of weldments, hydrogen embrittlement, environmentally assisted fatigue, grain boundary corrosion, and some kinds of intergranular stress corrosion cracking.[7] A very interesting and important field of study of impurity segregation processes involves AES of grain boundaries of materials. This technique includes tensile fracturing of special specimens directly inside the UHV chamber of the Auger Electron Spectrometer that was developed by Ilyin.[8][9] Segregation to grain boundaries can also affect their respective migration rates, and so affects sinterability, as well as the grain boundary diffusivity (although sometimes these effects can be used advantageously).[10]

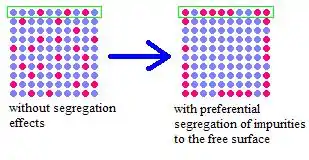

Segregation to free surfaces also has important consequences involving the purity of metallurgical samples. Because of the favorable segregation of some impurities to the surface of the material, a very small concentration of impurity in the bulk of the sample can lead to a very significant coverage of the impurity on a cleaved surface of the sample. In applications where an ultra-pure surface is needed (for example, in some nanotechnology applications), the segregation of impurities to surfaces requires a much higher purity of bulk material than would be needed if segregation effects did not exist. The following figure illustrates this concept with two cases in which the total fraction of impurity atoms is 0.25 (25 impurity atoms in 100 total). In the representation on the left, these impurities are equally distributed throughout the sample, and so the fractional surface coverage of impurity atoms is also approximately 0.25. In the representation to the right, however, the same number of impurity atoms are shown segregated on the surface, so that an observation of the surface composition would yield a much higher impurity fraction (in this case, about 0.69). In fact, in this example, were impurities to completely segregate to the surface, an impurity fraction of just 0.36 could completely cover the surface of the material. In an application where surface interactions are important, this result could be disastrous.

While the intergranular failure problems noted above are sometimes severe, they are rarely the cause of major service failures (in structural steels, for example), as suitable safety margins are included in the designs. Perhaps the greater concern is that with the development of new technologies and materials with new and more extensive mechanical property requirements, and with the increasing impurity contents as a result of the increased recycling of materials, we may see intergranular failure in materials and situations not seen currently. Thus, a greater understanding of all of the mechanisms surrounding segregation might lead to being able to control these effects in the future.[11] Modeling potentials, experimental work, and related theories are still being developed to explain these segregation mechanisms for increasingly complex systems.

Theories of Segregation

Several theories describe the equilibrium segregation activity in materials. The adsorption theories for the solid-solid interface and the solid-vacuum surface are direct analogues of theories well known in the field of gas adsorption on the free surfaces of solids.[12]

Langmuir–McLean theory for surface and grain boundary segregation in binary systems

This is the earliest theory specifically for grain boundaries, in which McLean[3] uses a model of P solute atoms distributed at random amongst N lattice sites and p solute atoms distributed at random amongst n independent grain boundary sites. The total free energy due to the solute atoms is then:

where E and e are energies of the solute atom in the lattice and in the grain boundary, respectively and the kln term represents the configurational entropy of the arrangement of the solute atoms in the bulk and grain boundary. McLean used basic statistical mechanics to find the fractional monolayer of segregant, , at which the system energy was minimized (at the equilibrium state), differentiating G with respect to p, noting that the sum of p and P is constant. Here the grain boundary analogue of Langmuir adsorption at free surfaces becomes:

Here, is the fraction of the grain boundary monolayer available for segregated atoms at saturation, is the actual fraction covered with segregant, is the bulk solute molar fraction, and is the free energy of segregation per mole of solute.

Values of were estimated by McLean using the elastic strain energy, , released by the segregation of solute atoms. The solute atom is represented by an elastic sphere fitted into a spherical hole in an elastic matrix continuum. The elastic energy associated with the solute atom is given by:

where is the solute bulk modulus, is the matrix shear modulus, and and are the atomic radii of the matrix and impurity atoms, respectively. This method gives values correct to within a factor of two (as compared with experimental data for grain boundary segregation), but a greater accuracy is obtained using the method of Seah and Hondros,[10] described in the following section.

Free energy of grain boundary segregation in binary systems

Using truncated BET theory (the gas adsorption theory developed by Brunauer, Emmett, and Teller), Seah and Hondros[10] write the solid-state analogue as:

where

is the solid solubility, which is known for many elements (and can be found in metallurgical handbooks). In the dilute limit, a slightly soluble substance has , so the above equation reduces to that found with the Langmuir-McLean theory. This equation is only valid for . If there is an excess of solute such that a second phase appears, the solute content is limited to and the equation becomes

This theory for grain boundary segregation, derived from truncated BET theory, provides excellent agreement with experimental data obtained by Auger electron spectroscopy and other techniques.[12]

More complex systems

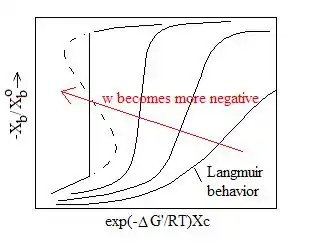

Other models exist to model more complex binary systems.[12] The above theories operate on the assumption that the segregated atoms are non-interacting. If, in a binary system, adjacent adsorbate atoms are allowed an interaction energy , such that they can attract (when is negative) or repel (when is positive) each other, the solid-state analogue of the Fowler adsorption theory is developed as

When is zero, this theory reduces to that of Langmuir and McLean. However, as becomes more negative, the segregation shows progressively sharper rises as the temperature falls until eventually the rise in segregation is discontinuous at a certain temperature, as shown in the following figure.

Guttman, in 1975, extended the Fowler theory to allow for interactions between two co-segregating species in multicomponent systems. This modification is vital to explaining the segregation behavior that results in the intergranular failures of engineering materials. More complex theories are detailed in the work by Guttmann[13] and McLean and Guttmann.[14]

The free energy of surface segregation in binary systems

The Langmuir–McLean equation for segregation, when using the regular solution model for a binary system, is valid for surface segregation (although sometimes the equation will be written replacing with ).[15] The free energy of surface segregation is . The enthalpy is given by

where and are matrix surface energies without and with solute, is their heat of mixing, Z and are the coordination numbers in the matrix and at the surface, and is the coordination number for surface atoms to the layer below. The last term in this equation is the elastic strain energy , given above, and is governed by the mismatch between the solute and the matrix atoms. For solid metals, the surface energies scale with the melting points. The surface segregation enrichment ratio increases when the solute atom size is larger than the matrix atom size and when the melting point of the solute is lower than that of the matrix.[12]

A chemisorbed gaseous species on the surface can also have an effect on the surface composition of a binary alloy. In the presence of a coverage of a chemisorbed species theta, it is proposed that the Langmuir-McLean model is valid with the free energy of surface segregation given by ,[16] where

and are the chemisorption energies of the gas on solute A and matrix B and is the fractional coverage. At high temperatures, evaporation from the surface can take place, causing a deviation from the McLean equation. At lower temperatures, both grain boundary and surface segregation can be limited by the diffusion of atoms from the bulk to the surface or interface.

Kinetics of segregation

In some situations where segregation is important, the segregant atoms do not have sufficient time to reach their equilibrium level as defined by the above adsorption theories. The kinetics of segregation become a limiting factor and must be analyzed as well. Most existing models of segregation kinetics follow the McLean approach. In the model for equilibrium monolayer segregation, the solute atoms are assumed to segregate to a grain boundary from two infinite half-crystals or to a surface from one infinite half-crystal. The diffusion in the crystals is described by Fick's laws. The ratio of the solute concentration in the grain boundary to that in the adjacent atomic layer of the bulk is given by an enrichment ratio, . Most models assume to be a constant, but in practice this is only true for dilute systems with low segregation levels. In this dilute limit, if is one monolayer, is given as .

The kinetics of segregation can be described by the following equation:[11]

where for grain boundaries and 1 for the free surface, is the boundary content at time , is the solute bulk diffusivity, is related to the atomic sizes of the solute and the matrix, and , respectively, by . For short times, this equation is approximated by:[11]

In practice, is not a constant but generally falls as segregation proceeds due to saturation. If starts high and falls rapidly as the segregation saturates, the above equation is valid until the point of saturation.[12]

In metal castings

All metal castings experience segregation to some extent, and a distinction is made between macrosegregation and microsegregation. Microsegregation refers to localized differences in composition between dendrite arms, and can be significantly reduced by a homogenizing heat treatment. This is possible because the distances involved (typically on the order of 10 to 100 μm) are sufficiently small for diffusion to be a significant mechanism. This is not the case in macrosegregation. Therefore, macrosegregation in metal castings cannot be remedied or removed using heat treatment.[17]

Further reading

- Lejcek, Pavel (2010). Grain boundary segregation in metals. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-642-12504-1.

- Shvindlerman, Günter Gottstein, Lasar S. (2010). Grain boundary migration in metals : thermodynamics, kinetics, applications (2nd ed.). Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781420054354.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

See also

References

- Lejcek, Pavel (2010). Grain boundary segregation in metals. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-642-12504-1.

- Shvindlerman, Günter Gottstein, Lasar S. (2010). Grain boundary migration in metals : thermodynamics, kinetics, applications (2nd ed.). Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781420054354.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McLean, Donald (1957). Grain Boundaries in Metals. Oxford University Press. p. 347.

- Westbrook, J. H. (1964). "Segregation at grain boundaries". Metallurgical Reviews. 9 (1): 415–471. doi:10.1179/mtlr.1964.9.1.415.

- Rellick, J. B.; McMahon, C. J. (1974). "Intergranular embrittlement of iron-carbon alloys by impurities". Metallurgical Transactions. 5 (11): 2439–2450. Bibcode:1974MT......5.2439R. doi:10.1007/BF02644027. S2CID 137038699.

- Harries, D. R.; Marwick, A. D. (1980). "Non-Equilibrium Segregation in Metals and Alloys". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 295 (1412): 197–207. Bibcode:1980RSPTA.295..197H. doi:10.1098/rsta.1980.0100. S2CID 123086175.

- Seah, M. P. (1979). "Quantitative prediction of surface segregation". Journal of Catalysis. 57 (3): 450–457. doi:10.1016/0021-9517(79)90011-3.

- Ilyin, A. M.; Golovanov, V. N. (1996). "Auger spectroscopy study of the stress enhanced impurity segregation in a Cr-Mo-V steel". Journal of Nuclear Materials. 233–237: 233–235. Bibcode:1996JNuM..233..233I. doi:10.1016/S0022-3115(96)00068-2.

- Ilyin, A. M. (1998). "Some features of grain boundary segregations in sensitized austenitic stainless steel". Journal of Nuclear Materials. 252 (1–2): 168–170. Bibcode:1998JNuM..252..168I. doi:10.1016/S0022-3115(97)00335-8.

- Seah, M. P.; Hondros, E. D. (1973). "Grain Boundary Segregation". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 335 (1601): 191. Bibcode:1973RSPSA.335..191S. doi:10.1098/rspa.1973.0121. S2CID 94481594.

- Seah, M. P. (1980). "Grain boundary segregation". Journal of Physics F: Metal Physics. 10 (6): 1043–1064. Bibcode:1980JPhF...10.1043S. doi:10.1088/0305-4608/10/6/006.

- Briggs, D.; Seah, M. P. (1995). Practical surface analysis Auger and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (2. ed., Reprint. ed.). Chichester [u.a.]: Wiley. ISBN 978-0471953401.

- Guttmann, M. (7 February 1980). "The Role of Residuals and Alloying Elements in Temper Embrittlement". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 295 (1413): 169–196. Bibcode:1980RSPTA.295..169G. doi:10.1098/rsta.1980.0099. S2CID 202574749.

- Guttmann, M.; McLean, D (1979). "Grain boundary segregation in multicomponent systems". In Blakely, J.M.; Johnson, W.C. (eds.). Interfacial Segregation: Papers presented at a seminar of the Materials Science Division of the American Society for Metals, October 22 and 23, 1977 (Reprinted ed.). Metals Park, Ohio: The Society. ISBN 978-0871700049.

- Wynblatt, P.; Ku, R. C. (1979). Blakely, J.M.; Johnson, W.C. (eds.). Interfacial Segregation: Papers presented at a seminar of the Materials Science Division of the American Society for Metals, October 22 and 23, 1977 (Reprinted ed.). Metals Park, Ohio: The Society. ISBN 978-0871700049.

- Rice, James R.; Wang, Jian-Sheng (January 1989). "Embrittlement of interfaces by solute segregation". Materials Science and Engineering: A. 107: 23–40. doi:10.1016/0921-5093(89)90372-9.

- Campbell, John (2003). Castings Principles: The New Metallurgy of Cast Metals (2nd ed.). Burlington, Mass.: Butterworth Heinemann. p. 139. ISBN 978-0750647908.