Self-propelled barge T-36

The self-propelled barge T-36 was a Soviet barge of the Project 306 type. Its waterline length is 17.3 m, width is 3.6 m, depth is 2 m, draft is 1.2 m. Tonnage is 100 tons, barge has two engines, speed is 9 knots.[1] The barge is known for drifting 49 days across the North Pacific Ocean in 1960, after being disabled, with all sailors on board surviving the journey by rationing a three-day's supply of food.

.png.webp) Philip Poplavsky - on the left. In the center - Askhat Ziganshin | |

| |

| Date | January 17th, 1960 |

|---|---|

| Duration | 49 days |

| Non-fatal injuries | 4 |

Background

In December 1959, all six of the self-propelled barges attached to the garrison of the Iturup island, were beached in order to wait out the period of winter storms and perform planned repairs. Ten-day emergency rations that were normally stored aboard, were sent to the depot. Shortly before January 17, 1960 the command had been alerted of a final supply ship's late arrival, and two of the six barges were dragged back to the water. Both received 1.5 tonnes of diesel fuel and, on January 15, a three-day supplies of water and food. Both, T-36 and T-97, were moored to a floating barrel approximately 500 feet offshore.[2]

Drift

Shortly after midnight of January 17, 1960, the barges were hit by a severe storm, accompanied with hurricane-force winds. The tackle was torn and the crew — Junior Sergeant tatar Askhat Ziganshin at the age 21; two ukrainians — Private Philip Poplavsky, Private Anatoly Kryuchkovsky at the age of 20; and one russian — Private Ivan Fedotov at the age 22 — started the barge's engines in attempt to stay away from the rocks. Weighing anchor away from the shore proved impossible due to poor visibility and strong winds; when, after 40–50 minutes' the wind pushed the barge too close to the shore, the engines were started again in order to navigate further away from it. This sequence repeated a few more times. Fighting with the storm continued for over 10 hours.

Eventually the eye of the storm passed over the island, and the wind reversed direction, this time pushing the barge away from the shore. The crew decided to run the barge aground, but when they attempted to do so, around 10 p.m., the engines ran out of fuel and stopped. The wind dragged the barge out of the lagoon and into the open ocean. The crew of T-97 had better luck and managed to successfully run their vessel aground.

The garrison command was aware of the crew struggle with the hurricane, but then radio communications ceased, as the barge's transmitter was rendered inoperable by the storm. As the storm subsided, search and rescue crew of 15 soldiers was deployed to sweep the seashore. The wreckage discovered by them, which included a lifebuoy and remnants of the wooden coal storage box, both marked with the barge's number, confirmed the suspicion that the barge has been sunk by the hurricane, and its crew perished. After the conclusion of search efforts, formal missing person notifications were sent to the families of the crew.

Ziganshin recorded the details into the vessel's deck log. From a recent newspaper found aboard, the crew learned that the area of the ocean the vessel was drifting towards (according to their personal estimate, which was later found to be incorrect) was being officially dedicated for ballistic missile testing for the period between January 15 and February 15. With that in mind, Ziganshin estimated that the chances of their rescue in the near future were extremely slim, and decided to strictly ration the available food and water. Nonetheless the crew manned the helm around the clock, "just in case".

On the second day of the drift, the crew performed the "stock-taking". The available supplies consisted of approximately two buckets of potatoes, a loaf of bread, three pounds of lard, a can and a half of canned meat, some fresh water in the teakettle (the 2-bucket-worth tank of fresh water was destroyed by the storm), a couple pounds of millet and dried peas, one carton of tea and one of coffee, and approximately fifty matches. The buckets of potatoes that were stored in the engine room got turned over by the storm, and the potatoes scattered over the floor and became sodden in diesel fuel. A significant amount, 120 litres (32 US gal), of fresh water, "red with rust, tasting like metal", was sourced from the engines' cooling system. In order to preserve even this supply, the crew, when possible, spread their bedsheets on the deck, allowing them to soak in rainwater, and then wrung the water out of them.

In order to keep themselves warm, the soldiers tended fire in the potbelly stove, utilizing available combustible materials, such as wooden crates, lifesavers, rags, paper scraps, old newspapers, and wooden planks from two of their beds. Once these easily available materials were exhausted, the crew eventually resorted to burning tires that served as the barge's fenders, filing pieces of rubber off them with a dull kitchen knife; each tire lasted about a week. After exhausting the available food supplies, the crew eventually ate their leather belts, wristlets, leather parts of their garmon and leather parts of their boots in attempts to quell the hunger.

Approximately 40 days' into their journey, they spotted a passing ship, but attempts to attract its attention failed; in the following days, two more ships passed by without noticing them. Finally, around 3 p.m. (local time) on March 7, after drifting for 49 days they were spotted by two S2Fs launched by USS Kearsarge in stormy waters 1,200 miles (1,900 km) off Wake Island, and consequently rescued.[3]

The drift of the crew was noticed by the worldwide press. Returning to the Soviet Union, the crew had popularity close to that of cosmonauts, and took a major role in Soviet popular culture.[4] The Soviet government expressed gratitude to the Kearsarge for its gesture.[5] The crew was soon returned home, first traveling to Paris on RMS Queen Mary and then flying to the USSR, as doctors recommended against taking a transatlantic flight.

Gallery

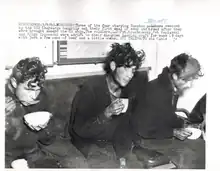

Kryuchkovsky, Poplavsky, Ziganshin consuming some soup and bread shortly after being rescued.

Kryuchkovsky, Poplavsky, Ziganshin consuming some soup and bread shortly after being rescued. Ivan Fedotov drinking coffee after being rescued. March 9, 1960.

Ivan Fedotov drinking coffee after being rescued. March 9, 1960. Askhat Ziganshin is being shaved for the first time in 49 days.

Askhat Ziganshin is being shaved for the first time in 49 days. Filipp Poplavsky getting a haircut for the first time in 49 days.

Filipp Poplavsky getting a haircut for the first time in 49 days. Fefotov, Ziganshin, Poplavsky on the deck of USS Kearsarge. March 14, 1960

Fefotov, Ziganshin, Poplavsky on the deck of USS Kearsarge. March 14, 1960

References

Citations

- (in Russian)

- Sergey Babakov (1999). ""Героем я себя никогда не считал"" [«I never considered myself a hero»]. Зеркало недели (in Russian). No. 11. Kyiv (published 1999-03-19). Archived from the original on 2020-06-26.

- "Deck Log Book of the U.S.S. Kearsarge CVS-33 — March 1960".

- (in Russian) Смена: 14.06.06. Асхат Зиганшин: «Кожаные сапоги мне дарят до сих пор» Archived 2012-02-08 at the Wayback Machine

- "USS Kearsarge Rescues Soviet Soldiers, 1960". History.navy.mil. Retrieved 2014-04-22.

Sources

- "Four Russians Adrift 49 Days Saved by U.S. Carrier in Pacific". The New York Times. New York. 1960-03-09. p. 1. ISSN 0362-4331.

- "Red Soldiers Recovering After Drifting 49 Days". The Honolulu Advertiser. Honolulu, Hawaii. 1960-03-09. p. 4 – via newspapers.com.

- "4 Russians Saved After Drifting 7 Weeks; Ate Shoes to Stay Alive". Chattanooga Daily Times. Chattanooga, Tennessee. 1960-03-09. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- "4 Russians Saved After Drifting 7 Weeks; Ate Shoes to Stay Alive". Chattanooga Daily Times. Chattanooga, Tennessee. 1960-03-09. p. 10 – via newspapers.com.

- "4 Rescued Soviet Seamen To Arrive in U.S. Today". Corpus Christi Times. Corpus Christi, Texas. 1960-03-15. p. 9 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- "For Rescued Red Sailors Reach S.F." Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Honolulu, Hawaii. 1960-03-15. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- "Moscow Hails Rescue Army Paper Notes U.S. Navy's Saving 4 Soldiers in Pacific". The New York Times. New York. 1960-03-13. p. 4. ISSN 0362-4331.

- "Russians Thank U.S. Sailors". The New York Times. New York. 1960-03-15. p. 12. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Max Frankel (1960-03-15). "U.S. Navy Rescue Pleases Moscow ; Finding of 4 Russians Adrift in Pacific Brings Wave of Goodwill to Americans". The New York Times. New York. p. 12. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Lawrence E. Davies (1960-03-16). "San Francisco Greets Four Russians Saved at Sea; 4 Soviet Sailors Welcomed in U.S." The New York Times. New York. p. 13. ISSN 0362-4331.

- "Khrushchev Halls U.S. For Rescue of 4 Sailors". The New York Times. New York. 1960-03-16. p. 17. ISSN 0362-4331.

- "4 Soviet Sailors Here; Men Rescued by U.S. Navy to Rest at Glen Cove". The New York Times. New York. 1960-03-18. p. 54. ISSN 0362-4331.

- "Saved at Sea Just in Time : U.S. Navy saves four Russians playing war". Time. Vol. 48, no. 11. 1960-03-21. pp. 26–27.

- "Soviet Sailors in Paris; Four Rescued by Americans Flying to Moscow Today". The New York Times. New York. 1960-03-29. p. 13. ISSN 0362-4331.

- "Moscow Lionizes 4 Rescued by U.S. Ship; Seamen Are Hailed on Return as New Communist Men". The New York Times. New York. 1960-03-29. p. 9. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Yevgeni Bugayenko, Stanislav Kalinichev, Alexander Turundayevsky (February 1981). "The Magnificent Four: Two Decades After". Soviet Life. pp. 48–54.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Public papers of the Presidents of the United States. Dwight D. Eisenhower 1960-61. Federal Register Division, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration. 1960-12-31. pp. 310–311.

- Alexey Timofeychev (2018-08-08). "49 days at sea: When the U.S. Navy saved Soviet soldiers in distress". Russia Beyond.

- Ruslan Budnik (2018-08-28). "49 days Adrift – USS Kearsarge Saved Soviet Sailors". War History Online.

- "USS Kearsarge Rescues Soviet Soldiers, 1960". Naval History and Heritage Command. 2018-05-04.