Semiconductor luminescence equations

The semiconductor luminescence equations (SLEs)[1][2] describe luminescence of semiconductors resulting from spontaneous recombination of electronic excitations, producing a flux of spontaneously emitted light. This description established the first step toward semiconductor quantum optics because the SLEs simultaneously includes the quantized light–matter interaction and the Coulomb-interaction coupling among electronic excitations within a semiconductor. The SLEs are one of the most accurate methods to describe light emission in semiconductors and they are suited for a systematic modeling of semiconductor emission ranging from excitonic luminescence to lasers.

Due to randomness of the vacuum-field fluctuations, semiconductor luminescence is incoherent whereas the extensions of the SLEs include[2] the possibility to study resonance fluorescence resulting from optical pumping with coherent laser light. At this level, one is often interested to control and access higher-order photon-correlation effects, distinct many-body states, as well as light–semiconductor entanglement. Such investigations are the basis of realizing and developing the field of quantum-optical spectroscopy which is a branch of quantum optics.

Starting point

The derivation of the SLEs starts from a system Hamiltonian that fully includes many-body interactions, quantized light field, and quantized light–matter interaction. Like almost always in many-body physics, it is most convenient to apply the second-quantization formalism. For example, a light field corresponding to frequency is then described through Boson creation and annihilation operators and , respectively, where the "hat" over signifies the operator nature of the quantity. The operator-combination determines the photon-number operator.

When the photon coherences, here the expectation value , vanish and the system becomes quasistationary, semiconductors emit incoherent light spontaneously, commonly referred to as luminescence (L). (This is the underlying principle behind light-emitting diodes.) The corresponding luminescence flux is proportional to the temporal change in photon number,[2]

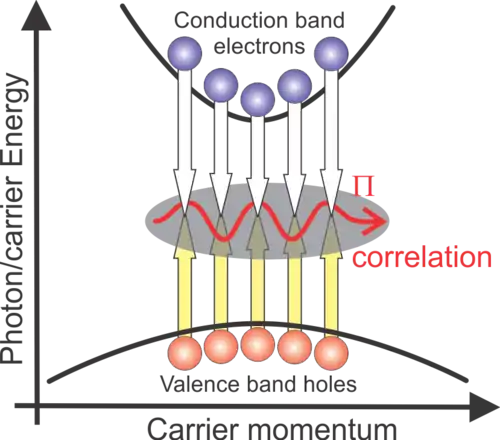

As a result, the luminescence becomes directly generated by a photon-assisted electron–hole recombination,

that describes a correlated emission of a photon when an electron with wave vector recombines with a hole, i.e., an electronic vacancy. Here, determines the corresponding electron–hole recombination operator defining also the microscopic polarization within semiconductor. Therefore, can also be viewed as photon-assisted polarization.

Many electron–hole pairs contribute to the photon emission at frequency ; the explicit notation within denotes that the correlated part of the expectation value is constructed using the cluster-expansion approach. The quantity contains the dipole-matrix element for interband transition, light-mode's mode function, and vacuum-field amplitude.

Principal structure of SLEs

In general, the SLEs includes all single- and two-particle correlations needed to compute the luminescence spectrum self-consistently. More specifically, a systematic derivation produces a set of equations involving photon-number-like correlations

whose diagonal form reduces to the luminescence formula above. The dynamics of photon-assisted correlations follows from

where the first contribution, , contains the Coulomb-renormalized single-particle energy that is determined by the bandstructure of the solid. The Coulomb renormalization are identical to those that appear in the semiconductor Bloch equations (SBEs), showing that all photon-assisted polarizations are coupled with each other via the unscreened Coulomb-interaction . The three-particle correlations that appear are indicated symbolically via the contributions – they introduce excitation-induced dephasing, screening of Coulomb interaction, and additional highly correlated contributions such as phonon-sideband emission. The explicit form of a spontaneous-emission source and a stimulated contribution are discussed below.

The excitation level of a semiconductor is characterized by electron and hole occupations, and , respectively. They modify the via the Coulomb renormalizations and the Pauli-blocking factor, . These occupations are changed by spontaneous recombination of electrons and holes, yielding

In its full form, the occupation dynamics also contains Coulomb-correlation terms.[2] It is straight forward to verify that the photon-assisted recombination[3][4][5] destroys as many electron–hole pairs as it creates photons because due to the general conservation law .

Besides the terms already described above, the photon-assisted polarization dynamics contains a spontaneous-emission source

Intuitively, describes the probability to find electron and hole with same when electrons and holes are uncorrelated, i.e., plasma. Such form is to be expected for a probability of two uncorrelated events to occur simultaneously at a desired value. The possibility to have truly correlated electron–hole pairs is defined by a two-particle correlation ; the corresponding probability is directly proportional to the correlation. In practice, becomes large when electron–hole pairs are bound as excitons via their mutual Coulomb attraction. Nevertheless, both the presence of electron–hole plasma and excitons can equivalently induce the spontaneous-emission source.

As the semiconductor emits light spontaneously, the luminescence is further altered by a stimulated contribution

that is particularly important when describing spontaneous emission in semiconductor microcavities and lasers because then spontaneously emitted light can return to the emitter (i.e., the semiconductor), either stimulating or inhibiting further spontaneous-emission processes. This term is also responsible for the Purcell effect.

To complete the SLEs, one must additionally solve the quantum dynamics of exciton correlations

The first line contains the Coulomb-renormalized kinetic energy of electron–hole pairs and the second line defines a source that results from a Boltzmann-type in- and out-scattering of two electrons and two holes due to the Coulomb interaction. The second line contains the main Coulomb sums that correlate electron–hole pairs into excitons whenever the excitation conditions are suitable. The remaining two- and three-particle correlations are presented symbolically by and , respectively.[2][6]

Interpretation and consequences

Microscopically, the luminescence processes are initiated whenever the semiconductor is excited because at least the electron and hole distributions, that enter the spontaneous-emission source, are nonvanishing. As a result, is finite and it drives the photon-assisted processes for all those values that correspond to the excited states. This means that is simultaneously generated for many values. Since the Coulomb interaction couples with all values, the characteristic transition energy follows from the exciton energy, not the bare kinetic energy of an electron–hole pair. More mathematically, the homogeneous part of the dynamics has eigenenergies that are defined by the generalized Wannier equation not the free-carrier energies. For low electron–hole densities, the Wannier equation produces a set of bound eigenstates which define the exciton resonances.

Therefore, shows a discrete set of exciton resonances regardless which many-body state initiated the emission through the spontaneous-emission source. These resonances are directly transferred to excitonic peaks in the luminescence itself. This yields an unexpected consequence; the excitonic resonance can equally well originate from an electron–hole plasma or the presence of excitons.[7] At first, this consequence of SLEs seems counterintuitive because in few-particle picture an unbound electron–hole pair cannot recombine and release energy corresponding to the exciton resonance because that energy is well below the energy an unbound electron–hole pair possesses.

However, the excitonic plasma luminescence is a genuine many-body effect where plasma emits collectively to the exciton resonance. Namely, when a high number of electronic states participate in the emission of a single photon, one can always distribute the energy of initial many-body state between the one photon at exciton energy and remaining many-body state (with one electron–hole pair removed) without violating the energy conservation. The Coulomb interaction mediates such energy rearrangements very efficiently. A thorough analysis of energy and many-body state rearrangement is given in Ref.[2]

In general, excitonic plasma luminescence explains many nonequilibrium emission properties observed in present-day semiconductor luminescence experiments. In fact, the dominance of excitonic plasma luminescence has been measured in both quantum-well[8] and quantum-dot systems.[9] Only when excitons are present abundantly, the role of excitonic plasma luminescence can be ignored.

Connections and generalizations

Structurally, the SLEs resemble the semiconductor Bloch equations (SBEs) if the are compared with the microscopic polarization within the SBEs. As the main difference, also has a photon index , its dynamics is driven spontaneously, and it is directly coupled to three-particle correlations. Technically, the SLEs are more difficult to solve numerically than the SBEs due to the additional degree of freedom. However, the SLEs often are the only (at low carrier densities) or more convenient (lasing regime) to compute luminescence accurately. Furthermore, the SLEs not only yield a full predictability without the need for phenomenological approximations but they also can be used as a systematic starting point for more general investigations such as laser design[10][11] and disorder studies.[12]

The presented SLEs discussion does not specify the dimensionality or the band structure of the system studied. As one analyses a specified system, one often has to explicitly include the electronic bands involved, the dimensionality of wave vectors, photon, and exciton center-of-mass momentum. Many explicit examples are given in Refs.[6][13] for quantum-well and quantum-wire systems, and in Refs.[4][14][15] for quantum-dot systems.

Semiconductors also can show several resonances well below the fundamental exciton resonance when phonon-assisted electron–hole recombination takes place. These processes are describable by three-particle correlations (or higher) where photon, electron–hole pair, and a lattice vibration, i.e., a phonon, become correlated. The dynamics of phonon-assisted correlations are similar to the phonon-free SLEs. Like for the excitonic luminescence, also excitonic phonon sidebands can equally well be initiated by either electron–hole plasma or excitons.[16]

The SLEs can also be used as a systematic starting point for semiconductor quantum optics.[2][17][18] As a first step, one also includes two-photon absorption correlations, , and then continues toward higher-order photon-correlation effects. This approach can be applied to analyze the resonance fluorescence effects and to realize and understand the quantum-optical spectroscopy.

See also

References

- Kira, M.; Jahnke, F.; Koch, S.; Berger, J.; Wick, D.; Nelson, T.; Khitrova, G.; Gibbs, H. (1997). "Quantum Theory of Nonlinear Semiconductor Microcavity Luminescence Explaining "Boser" Experiments". Physical Review Letters 79 (25): 5170–5173. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.79.5170

- Kira, M.; Koch, S. W. (2011). Semiconductor Quantum Optics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521875097.

- Li, Jianzhong (2007). "Laser cooling of semiconductor quantum wells: Theoretical framework and strategy for deep optical refrigeration by luminescence upconversion". Physical Review B 75 (15). doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.75.155315

- Berstermann, T.; Auer, T.; Kurtze, H.; Schwab, M.; Yakovlev, D.; Bayer, M.; Wiersig, J.; Gies, C.; Jahnke, F.; Reuter, D.; Wieck, A. (2007). "Systematic study of carrier correlations in the electron–hole recombination dynamics of quantum dots". Physical Review B 76 (16). doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.76.165318

- Shuvayev, V.; Kuskovsky, I.; Deych, L.; Gu, Y.; Gong, Y.; Neumark, G.; Tamargo, M.; Lisyansky, A. (2009). "Dynamics of the radiative recombination in cylindrical nanostructures with type-II band alignment". Physical Review B 79 (11). doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.79.115307

- Kira, M.; Koch, S.W. (2006). "Many-body correlations and excitonic effects in semiconductor spectroscopy". Progress in Quantum Electronics 30 (5): 155–296. doi:10.1016/j.pquantelec.2006.12.002

- Kira, M.; Jahnke, F.; Koch, S. (1998). "Microscopic Theory of Excitonic Signatures in Semiconductor Photoluminescence". Physical Review Letters 81 (15): 3263–3266. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.81.3263

- Chatterjee, S.; Ell, C.; Mosor, S.; Khitrova, G.; Gibbs, H.; Hoyer, W.; Kira, M.; Koch, S.; Prineas, J.; Stolz, H. (2004). "Excitonic Photoluminescence in Semiconductor Quantum Wells: Plasma versus Excitons". Physical Review Letters 92 (6). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.067402

- Schwab, M.; Kurtze, H.; Auer, T.; Berstermann, T.; Bayer, M.; Wiersig, J.; Baer, N.; Gies, C.; Jahnke, F.; Reithmaier, J.; Forchel, A.; Benyoucef, M.; Michler, P. (2006). "Radiative emission dynamics of quantum dots in a single cavity micropillar". Physical Review B 74 (4). doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.74.045323

- Hader, J.; Moloney, J. V.; Koch, S. W. (2006). "Influence of internal fields on gain and spontaneous emission in InGaN quantum wells". Applied Physics Letters 89 (17): 171120. doi:10.1063/1.2372443

- Hader, J.; Hardesty, G.; Wang, T.; Yarborough, M. J.; Kaneda, Y.; Moloney, J. V.; Kunert, B.; Stolz, W. et al. (2010). "Predictive Microscopic Modeling of VECSELs". IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 46: 810. doi:10.1109/JQE.2009.2035714

- Rubel, O.; Baranovskii, S. D.; Hantke, K.; Heber, J. D.; Koch, J.; Thomas, P. V.; Marshall, J. M.; Stolz, W. et al. (2005). "On the theoretical description of luminescence in disordered quantum structures". J. Optoelectron. Adv. M. 7 (1): 115.

- Imhof, S.; Bückers, C.; Thränhardt, A.; Hader, J.; Moloney, J. V.; Koch, S. W. (2008). "Microscopic theory of the optical properties of Ga(AsBi)/GaAs quantum wells". Semicond. Sci. Technol. 23 (12): 125009.

- Feldtmann, T.; Schneebeli, L.; Kira, M.; Koch, S. (2006). "Quantum theory of light emission from a semiconductor quantum dot". Physical Review B 73 (15). doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.73.155319

- Baer, N.; Gies, C.; Wiersig, J.; Jahnke, F. (2006). "Luminescence of a semiconductor quantum dot system". The European Physical Journal B 50 (3): 411–418. doi:10.1140/epjb/e2006-00164-3

- Böttge, C. N.; Kira, M.; Koch, S. W. (2012). "Enhancement of the phonon-sideband luminescence in semiconductor microcavities". Physical Review B 85 (9). doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.85.094301

- Gies, Christopher; Wiersig, Jan; Jahnke, Frank (2008). "Output Characteristics of Pulsed and Continuous-Wave-Excited Quantum-Dot Microcavity Lasers". Physical Review Letters 101 (6). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.067401

- Aßmann, M.; Veit, F.; Bayer, M.; Gies, C.; Jahnke, F.; Reitzenstein, S.; Höfling, S.; Worschech, L. et al. (2010). "Ultrafast tracking of second-order photon correlations in the emission of quantum-dot microresonator lasers". Physical Review B 81 (16). doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.81.165314

Further reading

- Jahnke, F. (2012). Quantum Optics with Semiconductor Nanostructures. Woodhead Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0857092328.

- Kira, M.; Koch, S. W. (2011). Semiconductor Quantum Optics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521875097.

- Haug, H.; Koch, S. W. (2009). Quantum Theory of the Optical and Electronic Properties of Semiconductors (5th ed.). World Scientific. p. 216. ISBN 978-9812838841.

- Piprek, J. (2007). Nitride Semiconductor Devices: Principles and Simulation. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH \& Co. KGaA. ISBN 978-3527406678.

- Klingshirn, C. F. (2006). Semiconductor Optics. Springer. ISBN 978-3540383451.

- Kalt, H.; Hetterich, M. (2004). Optics of Semiconductors and Their Nanostructures. Springer. ISBN 978-3540383451.