Darnestown, Maryland

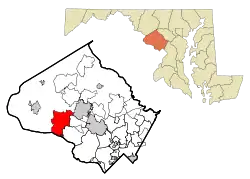

Darnestown is a United States census-designated place (CDP) and an unincorporated area in Montgomery County, Maryland. The CDP is 17.70 square miles (45.8 km2) with the Potomac River as its southern border and the Muddy Branch as much of its eastern border. Seneca Creek borders portions of its north and west sides. The Travilah, North Potomac, and Germantown census-designated places are adjacent to it, as is the city of Gaithersburg. Land area for the CDP is 16.39 square miles (42.4 km2). As of the 2020 census, the Darnestown CDP had a population of 6,723,[1] while the village of Darnestown is considerably smaller in size and population. Downtown Washington, D.C. is about 22 miles (35 km) to the southeast.

Darnestown, Maryland | |

|---|---|

| |

Location of Darnestown, Maryland | |

| Coordinates: 39°5′45″N 77°18′12″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 17.70 sq mi (45.8 km2) |

| • Land | 16.39 sq mi (42.4 km2) |

| • Water | 1.31 sq mi (3.4 km2) |

| Elevation | 377 ft (115 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 6,723 |

| • Density | 380/sq mi (150/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 20878, 20874, 20834 |

| Area code(s) | 301, 240 |

| FIPS code | 24-21825 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2389395 |

| Website | https://darnestowncivic.org/ |

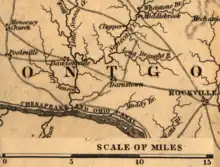

Within the Darnestown census-designated place at the intersection of what is now Darnestown Road and Seneca Road, the small village of Darnestown has existed since about 1800. The community had a population of 200 in 1878. The name Darnestown comes from William Darne, who owned the most land in the area at the beginning of the 19th century when the community post office opened. Settlement in the area began around 1750, and the tiny community was called Mount Pleasant, and then Darnes, before the name Darnestown began being used. The community thrived in the 19th century during the golden years of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, as the improved transportation facilities offered area farmers access to more markets. In the 1880 census, the United States Census Bureau began using a Minor Civil Division (MCD) category for aggregating populations, and the new Darnestown district had about 1,500 people. Growth stopped late in the 19th century when a new railway bypassed the community.

In the 1960s, affluent families began buying Montgomery County farmland for new housing and equestrian purposes. Today, many Darnestown CDP residents are wealthy and live in large homes on large lots, which is reflected in their high average income and low housing density. The median household income is nearly $228,000, and 73 percent of residents aged 25 years or more have at least a bachelor's degree or higher. The community benefits from its proximity to workplaces such as the Shady Grove Hospital area and the I-270 Technology Corridor. Washington is accessible by automobile or public transportation. Beginning with the 2000 census, the Census Bureau created a Darnestown census-designated place.

History

The first European (mostly Scottish and English) settlements in what would become Montgomery County, Maryland, were established in 1688, near Rock Creek and what was to become Rockville. The next stage of settlements was further west along the Potomac River near what is now Darnestown and Poolesville.[2] The land had been occupied by Native Americans of the Piscataway Confederation.[3] Ninian Beall was the first European landowner in the Darnestown area, settling around 1749.[4] His daughter Ruth Beall married Charles Gassaway, who built a brick home named Pleasant Hills around 1765. This was one of the first brick homes in what is now Montgomery County, and still stands today.[5] Gassaway purchased land from his father-in-law during the late 1700s—including land that would eventually become the Darnestown village. In the last half of the 18th century, a small village grew at the intersection of what is now Darnestown Road (Maryland Route 28) and Seneca Road (Maryland Route 112). At that time, Darnestown Road was called "the road from Georgetown to the mouth of the Monocacy River".[6] It was a Seneca Indian trail and is one of the oldest roads in Montgomery County.[7] Seneca Road led from Darnestown to the Seneca Mill and a landing on the Potomac River—a trip of less than four miles (6.4 km).[6][8]

Gassaway's daughter Elizabeth married William Darne in 1798. Darne was a civic leader who served in the Maryland House of Delegates, as a judge, and as director of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. He also became one of the area's biggest landowners.[9] The community was called Mount Pleasant until the establishment of a post office around 1803, when it gradually began being called "Darnes" in honor of its leading citizen.[10][Note 1] The Darnes name lasted until the mid–1820s, when the village became known as Darnestown.[13][Note 2] Darnestown's first store was kept by John Candler, and he is also cited as its first postmaster.[17] Leonard W. Candler was the Darnestown postmaster as early as 1828, and he was still listed as such in 1850 when Darnestown was one of 15 post offices in Montgomery County.[16][15][18] By the 1820s, the community had a wheelwright, mill, blacksmith, physician, and other businesses.[17]

Originally, Darnestown area land was used by European settlers for growing tobacco and corn. Construction of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (a.k.a. C&O Canal), which was operating between Georgetown and Seneca by June 1832, provided farmers with better access to markets. A network of roads and mills grew to connect farmers with the canal.[19] Mills in the area included the Seneca Mill (circa 1780), Black Rock Mill (built in 1815), and the DuFief Mill (established 1850).[19][6] Darne died in 1845, and his farm was eventually given to his son Alexander.[10] By 1860, farmers were growing corn, wheat and oats.[20] At the beginning of the American Civil War, Union Army leadership realized that the Potomac River area near Seneca was a possible crossing point for a Confederate invasion that could include Washington. The Darnestown area was occupied during 1861 by 18,000 Union troops. About half way between the canal and Darnestown, Major General Nathaniel P. Banks kept his headquarters at the Samuel Thomas Magruder farm where the Potomac River could be observed from high ground.[21] Troops from the 13th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment occupied the Pleasant Hills home originally built by the Gassaways.[22] After the war, Darnestown continued to be a farming community. An 1879 atlas lists 19 of 22 Darnestown "patrons" as farmers.[23]

In the 1870s, Darnestown's favorable transportation location suffered two setbacks that would affect future growth. First, freight traffic on the C&O Canal peaked in 1871, starting a downward trend that would end with the canal closing permanently in 1924.[24] Second, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad's new Metropolitan Branch opened in 1873 and bypassed Darnestown—running through Rockville, Gaithersburg, and Germantown.[25] These factors limited growth for Darnestown, as nearby communities on the new rail line had "unprecedented facilities" for "personal travel and transportation of productions and supplies".[26] The Darnestown Post Office, which had been operating for over 100 years, was discontinued May 31, 1911.[Note 3] The region around the Darnestown village did not exceed its 1890 population until after 1940, and the nearby villages of Hunting Hill, Travilah, and Seneca became essentially ghost towns.[Note 4] Darnestown grew very little until the 1960s, when wealthy families began buying farmland for living quarters and horseback riding. From 1970 to 1976, the population along Maryland Route 28 from Rockville to Darnestown nearly tripled.[30]

Historic places

The cornerstone for the Darnestown Presbyterian Church was laid on September 14, 1856 by a congregation organized in 1855. John L. DuFief, a community leader and owner of the DuFief Mill, donated 3 acres (1.2 ha) of land for the church. The completed structure was dedicated on May 22, 1858.[31] The building was expanded in the late 1890s, and a bell tower was added at that time. Stained glass windows were installed in 1905, and a rear wing was added in the 1950s. The church's cemetery contains the graves of some of the area's early settlers, including members of the Darne, Clagett, Offutt and Tschiffely families; Chesapeake and Ohio Canal lock keepers Pennifield, Violette, and Riley; and philanthropist Andrew Small.[32][31] Small's donation of $40,000 (equivalent to $879,400 in 2022) became the Andrew Small Academy, and its building was said to be the largest school house in the country at the time of its construction in 1869.[33] The three-story building became a public high school in 1907, and was demolished in 1955 when the present-day Darnestown Elementary School was built.[34]

Additional historic places include Black Rock Mill, located in Seneca Creek State Park.[35][36] The mill began operating in 1815, was run by Nicholas Offutt (a grandson of Ninian Beall) from 1866 until 1891, and continued operating into the 20th century.[37][38] The Samuel Thomas Magruder farmhouse, now privately owned, was headquarters for Major General Nathaniel P. Banks in 1861 during the American Civil War.[39][40][21] After Magruder and his wife died in the 1880s, the farm became the home of their daughter Mary and husband Wilson B. Tschiffely, who purchased the Seneca Mill in 1902.[40] Further south, Riley's Lock and Violette's Lock are located along the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (a.k.a. C&O Canal), and are now part of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park. The Pennyfield Lock, also part of the park, is located less than three miles (4.8 km) east of Violette's Lock—outside of the Darnestown census-designated place and within the Travilah census-designated place.[41][42] The community of Seneca exists on the edge of the Darnestown census-designated place, on Seneca Creek close to Riley's Lock and the Potomac River.[6] With the demise of the C&O Canal, Seneca lost its relevance. Today, a few homes, a schoolhouse, a store, ruins of two mills, and ruins of a quarry are all that remain.[43][44]

Geography

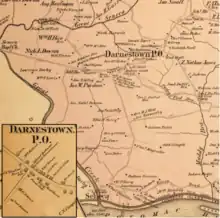

As an unincorporated area, Darnestown's boundaries are not officially defined. However, in 1878 the U.S. Census Bureau created a new Minor Civil Division (MCD) named Darnestown District (No. 6), that was used to aggregate portions of the county. The new district was created from the eastern portion of the Medley District and the western portion of the Rockville District.[17] The new Darnestown District was 40 square miles (100 km2) out of the county's total of 472 square miles (1,220 km2), making it fifth of eight districts in size.[45] The Darnestown/District 6 MCD was still used in the 1970 Census, and for Maryland it was shown as a county subdivision.[46] Little Seneca Creek and Great Seneca Creek formed the western border of this district. The Piney Branch and Dufief's Mill Road formed the District 6 eastern border. The Clarksburgh District (No. 2), which included Germantown, was on the north side of District 6, with Rockville Road forming the border. The Potomac River from Great Seneca Creek to the Piney Branch formed the southern border. Multiple C&O Canal Locks were included in District 6, and the communities of Seneca, Hunting Hill, and Travilah were part of District 6 in addition to Darnestown.[47]

In the 2000 census, the Census Bureau created a new Census-designated place (CDP) called Darnestown.[48] A Darnestown CDP was also used in the 2010 census. The Darnestown CDP has 16.39 square miles (42.4 km2) of land, which is smaller than the old Darnestown MCD.[49] The CDP uses the Muddy Branch, Turkey Foot Road, and Jones Lane for most of its eastern border instead of rivers further east. The MCD territory between Little Seneca Creek and the north side of Great Seneca Creek is also not part of the Darnestown CDP. Great Seneca Creek remains as the western border.[50] Washington, D.C. is roughly 25 miles (40 km) away.[51] The Travilah and North Potomac CDPs are along the Darnestown CDP's eastern border.[52] The United States Geological Survey lists ten Darnestown-related features, including the Darnestown Census Designated Place with an elevation of 377 feet (115 m) and the Darnestown populated place (a.k.a. Darnestown village) has an elevation of 440 feet (130 m).[53][Note 5]

ZIP codes

Despite having a post office for over 100 years until rural post offices were consolidated, there is no ZIP code used exclusively for Darnestown. ZIP codes for the area are mostly 20878 (which is also used for Gaithersburg and North Potomac) or 20874 (which is also used for Germantown). The region around Seneca uses 20834, which is a Poolesville ZIP code.[54] Examples of ZIP codes in various parts of the Darnestown CDP are 20878 for Darnestown Elementary School, 20874 for the former miller's house at Black Rock Mill, and 20834 at Riley's Lock.[55][38][56]

Climate

According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Darnestown has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[57] There are four distinct seasons, with winters typically cold with moderate snowfall, while summers are usually warm and humid. July is the warmest month, while January is the coldest. Average monthly precipitation ranges from about 2.5 to 4 inches (6.4 to 10.2 centimetres). The highest recorded temperature was 105.0 °F (40.6 °C) and the lowest recorded temperature was −13.0 °F (−25.0 °C).[58] There is a 50 percent probability that the first frost of the season will occur by October 21, and a 50 percent probability that the final frost will occur by April 16.[59]

| Climate data for Gaithersburg, MD (same zip code as part of Darnestown) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 40 (4) |

44 (7) |

53 (12) |

65 (18) |

73 (23) |

81 (27) |

85 (29) |

83 (28) |

76 (24) |

65 (18) |

55 (13) |

44 (7) |

64 (18) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 27 (−3) |

29 (−2) |

36 (2) |

46 (8) |

55 (13) |

64 (18) |

69 (21) |

67 (19) |

60 (16) |

48 (9) |

39 (4) |

31 (−1) |

48 (9) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.88 (73) |

2.81 (71) |

3.61 (92) |

3.22 (82) |

4.13 (105) |

3.49 (89) |

3.67 (93) |

2.90 (74) |

3.83 (97) |

3.29 (84) |

3.53 (90) |

3.00 (76) |

40.36 (1,026) |

| Source: Weather Channel[58] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 1,658 | — | |

| 1890 | 1,684 | 1.6% | |

| 1900 | 1,675 | −0.5% | |

| 1910 | 1,589 | −5.1% | |

| 1920 | 1,489 | −6.3% | |

| 1930 | 1,566 | 5.2% | |

| 1940 | 1,632 | 4.2% | |

| 1950 | 2,697 | 65.3% | |

| 1960 | 3,526 | 30.7% | |

| 1970 | 4,999 | 41.8% | |

| 2000 | 6,378 | — | |

| 2010 | 6,802 | 6.6% | |

| 2020 | 6,723 | −1.2% | |

| Note: Darnestown District 1880-1970 Darnestown CDP beg. 2000 Source: United States Census[Note 6] | |||

An 1879 history of Montgomery County describes the Darnestown village as having a population of 200 with a church, academy, public school, postmaster, two merchants, two millers, and 16 farmers.[64] The Darnestown District (No. 6) created around that time included the Darnestown village, Seneca, Hunting Hill, the small community eventually named Travilah, and farmland in between the communities.[47] The 1880 population for the Darnestown District was 1,658, while the population of the entire county was 24,759.[65]

2000 census

In the 2000 Census, a Darnestown census-designated place (CDP) was created.[48] County subdivision District 6 contained the Darnestown CDP, part of the city of Gaithersburg, part of the Germantown CDP, part of the North Potomac CDP, and part of the Travilah CDP.[66] The Darnestown CDP had a population of 6,378, with populations for the urban and rural portions of 3,391 and 2,987, respectively. No data were listed for 1990 and 1980.[63] The Darnestown CDP had 2,064 housing units, a total area of 17.69 square miles (45.8 km2), and a land area of 16.58 square miles (42.9 km2). (The difference between the two areas is water—mostly the Potomac River for Darnestown.) The average population per square mile of land (population density) was 384.6 inhabitants per square mile (148.5/km2), and the average number of housing units per square mile (housing density) was 124.5 (48.1 units per km2).[66]

2010 census

A portion of the Darnestown CDP is considered part of the Washington, DC–VA–MD Urbanized Area.[67] As of the 2010 U.S. census, the Darnestown CDP population was 6,802—a ranking of 162 for the state of Maryland.[68] Total land area was 16.39 square miles (42.4 km2) out of a total area of 17.70 square miles (45.8 km2)—which includes small differences from the areas used in the 2000 census. The population density was 415.0 inhabitants per square mile (160.2/km2). There were 2,275 housing units at an average density of 138.8 per square mile (53.6/km2).[69] These densities were much lower than county seat Rockville, where the District 4 portion had a population density of 4,403.3 inhabitants per square mile (1,700.1/km2) and a housing density of 1,779.3 units per square mile (687.0 units per km2).[70]

Current

As of 2018 estimates by the U.S. Census Bureau, Darnestown has a median household income of $227,962 and a poverty rate of 0.3 percent.[49] In Bloomberg's 2020 Index of the 200 richest communities within the United States, Darnestown was ranked 50th.[71] An estimated 2,209 households have an average of 2.9 persons living in them.[49] The percentage of residents under the age of 18 was 22.4, while 13.1 percent were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup was 52.0 percent male and 48.0 percent female.[49]

The racial makeup of the community was 74.6 percent White alone, 6.0 percent African American alone, 16.1 percent Asian alone, and 3.1 percent from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race was 6.9 percent of the population.[49] The educational attainment for the community is above the average for the United States, with 96.2 percent of Darnestown residents aged 25 years or more being a high school graduate or higher, while the same figure for the United States is 87.7 percent. A bachelor's degree or higher was attained by 72.6 percent of residents aged 25 or more.[49]

Government

Depending on which side of Darnestown Road they live, citizens of the Darnestown CDP are part of District 1, 2, or 3 of the Montgomery County Council.[72] The county council has representatives from each of five districts plus four at-large members. All members are elected at once and serve four-year terms.[73] In addition to the county council, Darnestown residents have an association that speaks for them. The Darnestown Civic Association is a volunteer organization that participates in numerous issues affecting the area and publishes a quarterly newsletter.[74]

Economy

The data based on the Census Bureau 2012 Survey of Business Owners lists 881 firms in Darnestown.[49] The number of firms with paid employees is 162, and those firms employ 1,068 people. The data are divided using the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS), and the Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services category (NAICS 54) is the leader in firms (78) and annual payroll ($16.3 million), while Retail Trade (NAICS 44-45) is the leader in number of paid employees (245) and sales ($74.7 million).[75] Educational Services (NAICS 61) is another important category.[75]

Darnestown is close to major employers such as Shady Grove Hospital and the technology companies along Interstate 270.[76] Over 25 biotech companies and over 25 technology companies have facilities in the I-270 Technology Corridor in the Rockville, Gaithersburg, or Germantown area.[77] Darnestown residents who commute further distances to work typically use Interstate 270 or River Road to the Capital Beltway. The Washington Metro system, especially the Red Line, is also available.[76]

Darnestown residents have a small set of shops located at the intersection of Darnestown Road and Seneca Road, including a grocery store, gas station, bank, and other stores. That intersection may also be the site of a lost cemetery that contained some members of the Darne family.[78] Two more shopping centers are located further east on Darnestown Road: Quince Orchard Market Place and The Shops at Potomac Valley.[79] Additional shopping is available at Germantown, North Potomac, and Gaithersburg. Closer to the Potomac River, the Potomac Village Shopping Center and Potomac Promenade are available in Potomac.[80] Based on 2012 census data, total retail sales for the Darnestown CDP were $64.1 million.[49]

Infrastructure

Transportation

Maryland Route 28, a state highway, connects Darnestown with Rockville and provides access to Interstate 270.[50] Other major roads in the Darnestown CDP are Germantown Road/Maryland Route 118, Seneca Road/Maryland 112, and River Road/Maryland Route 190.[50] Maryland's Interstate 270 is a major north–south interstate highway east of Darnestown that connects with Washington's Capital Beltway (a.k.a. Interstate 495).[81] Interstate 370 and the Intercounty Connector toll road (MD 200) are nearby major east–west highways that connect to Interstate 95.[82]

Portions of the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority's Metrorail system are located in Montgomery County, and Red Line stations on the west side of the county are closest to Darnestown.[83] Among those west side Metro stations are Shady Grove (Gaithersburg), Rockville, and Twinbrook (south Rockville). Those approaching from River Road often use the Grosvenor-Strathmore station.[84] A Montgomery County Ride-On bus runs through the Darnestown village and connects riders with Shady Grove Metro station via a route that includes stops at Seneca-Darnestown and Quince Orchard-Darnestown on Darnestown Road.[85]

Utilities

Darnestown's electric power is provided by Pepco (Potomac Electric Power Company), which serves much of Montgomery County, portions of Prince George's County, and all of the District of Columbia.[86] Washington Gas provides natural gas service to residents and businesses.[87] Curbside garbage, recycling, and yard waste collection and disposal are not provided by the county, and independent contractors must be used. The Shady Grove Processing Facility and Transfer Station, a county waste collection facility located in Rockville, is available for drop off of garbage, recycling, and yard debris.[88] The Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission (WSSC) provides water and wastewater treatment for Darnestown.[89] Drinking water comes from the WSSC treatment facility on the Potomac River, while sewage is treated at a plant in the District of Columbia.[90]

Healthcare

The nearest general hospital is the Adventist HealthCare Shady Grove Medical Center in Rockville.[91] This medical facility has a five-star rating from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.[92] Adventist Health Care has multiple satellite locations, including its Adventist HealthCare Germantown Emergency Center on Germantown Road.[93] MedStar Health Urgent Care in Gaithersburg is located in The Shops at Potomac Valley on Darnestown Road near Quince Orchard High School.[94]

Education

Darnestown is served by Montgomery County Public Schools. The majority of public high school students attend Northwest High School, while a small number of residents on the eastern side attend Quince Orchard High School.[95] Northwest High School is located in Germantown.[96] Quince Orchard High School is located at the intersection of Quince Orchard Road and Darnestown Road, and uses a Gaithersburg address.[97] Elementary schools include Darnestown Elementary and Jones Lane Elementary.[55][98] Private schools in the area include Butler Montessori, Mary of Nazareth Catholic School, and Seneca Academy.[99][100][101]

Higher education

Montgomery College has a Germantown campus known as the Pinkney Innovation Complex for Science and Technology.[102] It also has a campus in Rockville and a training center in Gaithersburg.[103] The Universities at Shady Grove is located within North Potomac and offers select degree programs from nine public Maryland universities.[104] Instead of being a university itself, this campus partners with other universities and offers courses for 80 upper-level undergraduate, graduate degree, and certificate programs. The participating universities handle admissions.[105] Johns Hopkins University has a campus in Rockville near the Universities at Shady Grove.[106]

Public library

Several libraries are located not far from Darnestown, including three that are part of the Montgomery County Public Library system. Quince Orchard library is closest to the Darnestown village, located across the street from Quince Orchard High School in North Potomac.[107] Germantown Library opened in 2007, and is located north of Northwest High School in Germantown.[108][109] Rockville Memorial Library, a larger library also part of the county system, is located in Rockville three blocks from the Rockville Metro station.[110] While the Rockville Memorial Library celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2001, Quince Orchard Library was only a year old at that time.[111] A fourth county library is close to those who live near River Road.[112] Potomac library opened in 1985, and has been upgraded since that time.[113] Priddy Library is part of the University of Maryland Libraries system and is located at the Universities at Shady Grove in North Potomac.[114] The Priddy Library opened in 2007.[115]

Culture

Arts

Close to the intersection of Darnestown Road and Seneca Road is the 0.6-acre (0.24 ha) Darnestown Heritage Park, which is a small county park that functions as an outdoor museum using a series of historical markers that tell the history of Darnestown.[116] Black Rock Mill is a partially restored mill in Seneca Creek State Park that exhibits the workings of a mill from the 19th century.[117] Riley's Lock and lock house are part of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park, and a history program run by local Girl Scouts includes tours of the lock house during spring and fall afternoons.[118][119]

Darnestown does not have art centers of its own, but some museums can be found in adjacent communities. The Beall–Dawson House, built circa 1815, contains exhibits on life in 19th century Rockville.[120] The Gaithersburg Community Museum is located in an old Baltimore and Ohio Railroad complex in Olde Town Gaithersburg, and focuses on educating children about Gaithersburg history.[121] Glenstone Modern Art Museum is east of Darnestown near the intersection of Travilah Road and Glen Road, and has indoor and outdoor exhibits.[122] The Strathmore Music and Arts Center in North Bethesda has a concert hall and art exhibits.[123]

Parks and recreation

Seneca Creek State Park is an irregular-shaped park of 6,300 acres (2,500 ha) that follows Seneca Creek for 14 miles (23 km) from beyond Clopper Lake (northern part of Darnestown CDP) to the Potomac River (southern part of Darnestown CDP). The park has 50 miles (80 km) of trails for hiking, horseback riding and biking.[124][125] Riley's Lock and Violette's Lock are two canal locks in the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park that are within the Darnestown CDP, and the Pennyfield Lock is nearby.[126][127][128] These locks are used by kayakers, bikers, and hikers, and are also good places to observe wildlife.[129] The 40–acre (16 ha) Dierssen Waterfowl Sanctuary is located at towpath marker 20.0 between Violette's Lock and the Pennyfield Lock.[130]

The Darnestown CDP has six county parks and an undeveloped conservation area. The Berryville Road Neighborhood Conservation Area is 3.83 acres of undeveloped woodland located between Seneca Road and Seneca Creek.[131] Darnestown Heritage Park and Darnestown Local Park are located in the Darnestown village. The local park is 10 acres (4.0 ha) in size, and has a playground, softball field, small multi-use field, and two tennis courts.[132] More county parks are located close to the Potomac River, including the Seneca Landing Special Park that has a boat landing near Riley's Lock.[133] The 630-acre (250 ha) Blockhouse Point Conservation Park, which has views of the Potomac River and ruins from the American Civil War, is also located along the Potomac River and C&O Canal.[134] The Callithea Farm Special Park is a 91-acre (37 ha) horse farm.[135] A sixth park, Muddy Branch Stream Valley Park, is 876 acres (355 ha) that follow the Muddy Branch and contains the Muddy Branch Greenway Trail.[136]

The Montgomery County Park System has over 200 miles (320 km) of hiking trails.[137] Among those trails is the Muddy Branch Greenway Trail, which passes North Potomac's Potomac Horse Center on a 9-mile (14 km) route between Darnestown Road and Blockhouse Point Conservation Park near the Potomac River.[138] The Potomac Horse Center, located adjacent to the Darnestown CDP, is a special county park that offers training for horses and riders.[139] Construction of the Powerline Trail (a.k.a. Pepco Trail) began in 2018, and this trail will connect Muddy Branch Stream Valley Park with the South Germantown Recreation Park, which is the home of the Maryland SoccerPlex.[140][141] The Maryland SoccerPlex is located less than 5 miles (8.0 km) from the Darnestown village and has indoor and outdoor facilities for soccer and other activities.[142]

Notes

Footnotes

- A post office called "Darnes" is listed in an 1803 post office directory.[11] Another post office source uses 1804 as the start date for the Darnes Post Office. (To find United States Post Office start and end dates for Darnestown, go to the Postmaster Finder web site and select Maryland from the drop-down box. Click Search to process.[12]

- One source says the post office called the village "Darnes" from 1804 until 1824, and then it was called "Darnestown".[14] A post office directory for 1816 confirms that the post office called the community Darnes at that time.[15] An 1828 post office directory lists a Darnestown Post Office.[16]

- To find United States Post Office start and end dates for Darnestown, go to the Postmaster Finder web site and select Maryland from the drop-down box. Click Search to process.[12]

- The Hunting Hill Post Office closed in 1905, and its only store was converted to a residence in 1929.[27] The Seneca school closed in 1910.[28] In 1918, the Travilah Hall Company defaulted on its mortgage for the community's town hall.[29]

- The Darnestown CDP has a latitude of 390545N and a longitude of 0771812W.[53] The Geographic Names Information System uses an ANSI Code for Darnestown of 02389395 and a Place Identifier of 2421825. Darnestown has a GIS ID of 287 and a FID of 286. The State FIPS code is 24 and the Place FIPS is 21825.[52]

- Source for 1880 and 1890, is the 1890 Census.[60] Other sources are: for 1900-1920, the 1920 Census;[61] for 1930-1950, the 1950 Census;[62] and for 1960 and 1970, the 1970 Census.[46] The 2000 U.S. Census lists a Darnestown population for 2000, but is blank for 1990 and 1980.[63] The source for 2010 and 2020 is the 2020 Census.[1]

Citations

- "QuickFacts: Darnestown CDP, Maryland". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- Boyd 1879, p. 43

- Montgomery County Historical Society 1999, p. 3

- "Maryland Historical Trust Determination of Eligibility Form - Darnestown Historic District" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Maryland Government. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- "Montgomery County Historic Preservation Commission Staff Report - Pleasant Hills" (PDF). Montgomery Planning. Montgomery County Maryland Government. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- "Capsule Summary Seneca Creek State Park" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Maryland government. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- Curtis 2020, p. 76

- Fielding Lucas Jr. (1841). Map of the State of Maryland (from Lib. of Congress) (Map). Baltimore, Maryland: Fielding Lucas, Jr. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "Montgomery County Department of Parks - Facility Plan for Darnestown Square Urban Park" (PDF). Montgomery County Department of Parks. The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- "Capsule Summary for the Darne-Purdum Farm" (PDF). King Farm Dairy Mooseum. Maryland government and Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- United States Post Office Department 1803, p. 11

- "Postmaster Finder - Post Offices by State - Maryland Post Offices". United States Post Office. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- Kenny 1984, p. 75

- "Guide to the Checklist of Maryland Post Offices" (PDF). The Urban Historians. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- "Maryland Post Offices 1816". USGenWeb Archives. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- United States Post Office Department 1828, p. 28

- Scharf 1882, p. 761

- Tremayne 1850, p. 75

- Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, p. 12

- Montgomery County Historical Society 1999, pp. 6–7

- Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, p. 216

- Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, pp. 208–209

- Hopkins 1879, p. 28

- "Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park". National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- "The Montgomery County Story - Train Stations and Suburban Development Along the Old Baltimore and Ohio Railroad" (PDF). The Montgomery County Historical Society. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- Boyd 1879, p. 83

- "Individual Property/District Maryland Historical Trust Internal NR-eligibility Review Form - Hunting Hill Store and P.O." (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Maryland Government. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- Buglass 2015, p. 2

- "Maryland Historical Trust Inventory form for State Historic Sties Survey - Travilah Hall" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Maryland Government. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- Sableman, Mark (July 21, 1977). "Route 28: Road from the Rural Past to the Urban Present". Washington Post. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, p. 218

- Scharf 1882, pp. 761–762

- Scharf 1882, p. 762

- "Capsule Summary for Andrew Small Academy Site" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- Curtis 2020, p. 75

- "Seneca Creek State Park - Trail System and Maps" (PDF). Maryland Park Service. Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Addendum - Black Rock Mill" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Maryland Government. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Capsule Summary for Black Rock Miller's House" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Maryland Government. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- Orton, Kathy (February 8, 2013). "Maryland Farm has a Notable, and Notorious, History". Washington Post. Katharine Weymouth. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- "Capsule Summary for Samuel Thomas Magruder Farm" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Maryland Government. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- "C&O Canal – Pennyfield, Violette's and Riley's Locks". Maryland/DC Birding Guide. Maryland Ornithological Society. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- "Lock 23 (Violettes Lock) & Dam No. 2". C&O Canal Trust. C&O Canal Trust. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- "Tour of Historic Seneca Maryland with the Historical Society of Washington, DC". DC Preservation League. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- "Tschiffely Mill at Seneca". Gaithersburg Then and Now. Shaun Curtis. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- Hopkins 1879, p. 36

- United States Census Bureau 1973, p. 22-18

- G. M. Hopkins (1879). Atlas of Fifteen Miles Around Washington...Image 26 Darnestown Dist. No. 6 (from Lib. of Congress) (Map). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: F. Bourquin's Steam Lithographic Press. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- United States Census Bureau 2003, p. III-6

- "Quick Facts - Darnestown CDP, Maryland". United States Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

- "Darnestown, CDP, Maryland - Place Selection Map". United States Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

- "Montgomery County, MD: Close to the Action". Visit Montgomery. Conference and Visitors Bureau of Montgomery County, MD, Inc. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Maryland Census Designated Areas - Census Designated Places 2010 (Data Tab with Darnestown, MD, USA search)". Maryland.gov. Maryland government. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- "Darnestown CDP". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. February 19, 2008. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

- "Service Regions and ZIP codes in Montgomery County". Montgomery County, Maryland government. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- "Darnestown Elementary". Montgomery County Public Schools. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- "Riley's/Seneca Parking". C&O Canal Trust. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- "Updated World Map of the Koppen-Geiger Climate Classification". Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. European Geosciences Union. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "Gaithersburg, MD Monthly Weather". The Weather Channel. TWC Product and Technology LLC. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- "Freeze / Frost Occurrence Data (Rockville, Maryland)" (PDF). NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- United States Census Bureau 1895, p. 178

- United States Census Bureau 1925, p. 454

- United States Census Bureau 1953, p. 20-10

- United States Census Bureau 2003, p. 16

- Boyd 1879, pp. 126–127

- Scharf 1882, p. 655

- United States Census Bureau 2003, p. 9

- United States Census Bureau 2012, p. IV-2

- United States Census Bureau 2012, p. 44

- United States Census Bureau 2012, pp. 28–29

- United States Census Bureau 2012, p. 18

- Locke, Taylor (February 21, 2020). "These are the Top 10 Richest Places in America". CNBC. CNBC LLC, a Division of NBC Universal. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- "Montgomery County Council (map)". Montgomery County Council. Montgomery County Government. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- "Montgomery County Council - About the Council". Montgomery County Council. Montgomery County Government. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- "Welcome to Darnestown - Official Website of the Darnestown Civic Association". Darnestown Civic Association. Darnestown Civic Association. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- "Darnestown, CDP, Maryland - Statistics for All U.S. Firms by Industry, Gender, Ethnicity, and Race for the U.S., States, Metro Areas, Counties, and Places: 2012". United States Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- Straight, Susan (February 8, 2013). "Neighborhood Profile: Flints Grove". Washington Post. Katharine Weymouth. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "I 270 Technology Corridor Report". Germantown-Gaithersburg Chamber of Commerce. Germantown-Gaithersburg Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- Aguilar, Louis (February 27, 1994). "Development Plans Unearth Grave Concerns". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- "Montgomery County Planning Department - Darnestown Valley—WHM LLC and Darnestown Valley Petroleum WHM LLC" (PDF). Montgomery Planning Board. Montgomery County Planning Department. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- "Montgomery County Planning Department - Potomac Village" (PDF). Montgomery Planning Board. Montgomery County Planning Department. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

- United States Department of Transportation & Maryland Department of Transportation 2002, p. 12

- "Intercounty Connector (ICC)/MD 200". Maryland Transportation Authority - Intercounty Connector (ICC)/MD 200. Maryland Transportation Authority. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "Montgomery, Maryland - Washington DC". MD DC Montgomery, Maryland. Conference and Visitors Bureau of Montgomery County, MD, Inc. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "Metro System Map" (PDF). Metro System Map. Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "Route 76 Weekday Schedule - Poolesville to Shady Grove". Montgomery County Department of Transportation. Montgomery County, Maryland, Government. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- "Pepco - About Us". Potomac Electric Power Company. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "Washington Gas Service Territory". Washington Gas. WGL Holdings, Inc. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "Shady Grove Processing Facility and Transfer Station". Department of Environmental Protection of Montgomery County, Maryland. Montgomery County Government. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "WSSC - Project Locations". Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "Public Water & Sewer Service (Where Does Your Water Come From?) and (Where Does Your Wastewater Go?)". Department of Environmental Protection of Montgomery County, Maryland. Montgomery County Government. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "Adventist HealthCare Shady Grove Medical Center". Adventist HealthCare. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "Adventist HealthCare Shady Grove Medical Center Earns Five-Star Rating from Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services". Adventist HealthCare. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "Adventist HealthCare Germantown Emergency Center". Adventist HealthCare. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- "MedStar Health Urgent Care in Gaithersburg, MD". MedStar Health. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- Montgomery County Public Schools (Maryland) (2020). Northwest HS Service Area 2021-2022 (PDF) (Map). Rockville, Maryland: Montgomery County Public Schools Division of Capital Planning. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Northwest High School". Montgomery County Public Schools. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- "Quince Orchard High School Map + Directions". Montgomery County Public Schools. Montgomery County Public Schools. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- "Jones Lane Elementary". Montgomery County Public Schools. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- "Butler Montessori". Butler Montessori. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- "Mary of Nazareth Catholic School". Mary of Nazareth School. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- "Seneca Academy". Seneca Academy. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- "Montgomery College Germantown Campus - Pinkney Innovation Complex for Science and Technology (PIC MC)". Montgomery College. Montgomery College. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- "Montgomery College". Montgomery College. Montgomery College. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "The Universities at Shady Grove - About USG". The Universities at Shady Grove. The Universities at Shady Grove. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "The Universities at Shady Grove - USG at a Glance" (PDF). The Universities at Shady Grove. The Universities at Shady Grove. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- "Johns Hopkins University - Montgomery County". Johns Hopkins University - Montgomery County. Johns Hopkins University - Montgomery County. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- "Montgomery County Public Libraries - Quince Orchard Library". Montgomery County Public Libraries. Montgomery County Government. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "Montgomery County Public Libraries - Germantown Library". Montgomery County Public Libraries. Montgomery County Government. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- "Friends of the Library - Germantown Chapter". Friends of the Library. Friends of the Library, Montgomery County, Maryland Inc. Retrieved August 25, 2020.

- "Montgomery County Public Libraries - Rockville Memorial Library". Montgomery County Public Libraries. Montgomery County Government. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- Ruben, Barbara (April 26, 2001). "Library Celebrates 50th Anniversary". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- "Montgomery County Public Libraries - Potomac Library". Montgomery County Public Libraries. Montgomery County Government. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- "CountyStat - Potomac Library Renovation". Montgomery County, Maryland. Montgomery County Government. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- "The Universities at Shady Grove - Priddy Library". The Universities at Shady Grove. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- Zdravkovska 2011, p. 135

- "Darnestown Heritage Park". Montgomery County, Maryland - Montgomery Parks. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- "Addendum Black Rock Mill" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- Oman, Anne H. (February 15, 1985). "Reliving the Lockhouse Life". Washington Post. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "Riley's Lockhouse (Girl Scouts)". C&O Canal Trust. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "Montgomery History - Beall-Dawson House". Montgomery County Historical Society. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- "Gaithersburg Community Museum". Gaithersburg, Maryland government. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- Ramanathan, Lavanya; Hahn, Fritz (October 3, 2018). "Going to Glenstone? Here's what you need to know about D.C.'s new must-see art museum". Washington Post. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- Mir, A.; Spivack, Matthew; Mosk, A. (February 6, 2005). "Strathmore A High Note For County". Washington Post. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- "Seneca Creek State Park". Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Maryland government. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Capsule Summary - Seneca Creek State Park" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Maryland Government. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- "Chesapeake & Ohio Canal - National Historical Park". National Park Service. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- "Riley's Lock & Seneca". C&O Canal Trust. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- "Lock 23 (Violettes Lock) & Dam No. 2". C&O Canal Trust. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- "C&O Canal – Pennyfield, Violette's & Riley's Locks". The Maryland Ornithological Society. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- "Dierssen Waterfowl Sanctuary". C&O Canal Trust. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "Berryville Road Neighborhood Conservation Area". Montgomery County, Maryland - Montgomery Parks. Montgomery County, Maryland. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- "Darnestown Local Park". Montgomery County, Maryland - Montgomery Parks. Montgomery County, Maryland. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Seneca Landing Special Park". Montgomery County, Maryland - Montgomery Parks. Montgomery County, Maryland. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Blockhouse Point Conservation Park & Trails". Montgomery County, Maryland - Montgomery Parks. Montgomery County, Maryland. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- "Callithea Farm Special Park". Montgomery County, Maryland - Montgomery Parks. Montgomery County, Maryland. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- "Muddy Branch Stream Valley Park". Montgomery County, Maryland - Montgomery Parks. Montgomery County, Maryland. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- "Montgomery County, Maryland - Montgomery Parks - Park Trails". Montgomery County, Maryland - Montgomery Parks. Montgomery County, Maryland. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "Montgomery County, Maryland - Montgomery Parks - Muddy Branch Greenway Trail". Montgomery County, Maryland - Montgomery Parks. Montgomery County, Maryland. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "Montgomery County, Maryland - Montgomery Parks - Potomac Horse Center Special Park". Montgomery County, Maryland - Montgomery Parks. Montgomery County, Maryland. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- Zimmermann, Joe (January 25, 2018). "Officials Break Ground on Trail Between North Potomac and Germantown". Bethesda Magazine. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- "Powerline Trail". Montgomery County, Maryland - Montgomery Parks. Montgomery County, Maryland. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- "Maryland SoccerPlex & Adventist Healthcare Fieldhouse". Maryland Soccer Foundation, Inc. Maryland Soccer Foundation, Inc. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

References

- Boyd, T. H. S. (1879). The History of Montgomery County, Maryland, From its Earliest Settlement in 1650 to 1879. Clarksburg, MD [Baltimore]: W.K. Boyle & Son. OCLC 79381943.

- Buglass, Ralph (2015). The Montgomery County Story (Teaching Yet Today: A Century of One- and Two-Room Schools) (PDF). Rockville, Maryland: Montgomery County Historical Society. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- Curtis, Shaun (2020). Around Gaithersburg. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-46710-462-3. OCLC 1124337558.

- Hopkins, Griffith Morgan (1879). Atlas of Fifteen Miles around Washington, Including the County of Montgomery, Maryland. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: F. Bourquin.

- Kelly, Clare Lise; Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission (2011). Places from the Past: The Tradition of Gardez Bien in Montgomery County, Maryland - 10th Anniversary Edition (PDF). Silver Spring, Maryland: Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission. ISBN 978-0-97156-070-3. OCLC 48177160. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- Kenny, Hamill (1984). The Place Names of Maryland, their Origin and Meaning. Baltimore, Maryland: Museum and Library of Maryland History, Maryland Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-93842-029-3. OCLC 11759536.

- Montgomery County Historical Society (1999). Montgomery County, Maryland - Our History and Government (PDF). Rockville, Maryland: Montgomery County Government Office of Public Relations.

- Scharf, J. Thomas (1882). History of western Maryland: Being a History of Frederick, Montgomery, Carroll, Washington, Allegany, and Garrett counties from the Earliest Period to the Present Day; Including Biographical Sketches of their Representative Men. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: L.H. Everts. OCLC 2955029. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- Tremayne, Edward (1850). Tremayne's Table of Post-offices in the United States: Arranged Alphabetically by States and Counties, Giving the Name of Post-office and Postmaster; Also, Exhibiting the Distances from the Capital of the United States to the Capital of the Several States and Territories. New York, New York: W.F. Burgess. OCLC 17215595.

- United States Census Bureau (1895). Eleventh Census of the United States, 1890. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 273634. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- United States Census Bureau (1925). Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 62443371. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- United States Census Bureau (1953). 1950 Census of Population. Volume 1 : Number of Inhabitants - Maryland (PDF). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 27693887. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- United States Census Bureau (1973). 1970 Census of Population. Volume 1 : Characteristics of the Population. Part 22 : Maryland. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 27693887. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- United States Census Bureau (2003). 2000 Census of Population and Housing, Population and Housing Unit Counts, Maryland. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-1-42898-581-0. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- United States Census Bureau (2012). Maryland: 2010 - Population and Housing Unit Counts (PDF). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- United States Department of Transportation; Maryland Department of Transportation (2002). Multi-Modal Corridor Study, Frederick and Montgomery Counties, Maryland - Draft Environmental Impact Statement and Section 4(f) Evaluation Volume 2 of 2. Baltimore, MD: Maryland Department of Transportation. OCLC 49960675. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- United States Post Office Department (1803). Volume 6: List of the Post-Offices in the United States [Manuscript/Mixed Material retrieved from the Library of Congress]. Washington City: Printed by Order of the Post-Master-General. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- United States Post Office Department (1828). United States Official Postal Guide. New York, New York: Hurd & Houghton. OCLC 40371095. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- Zdravkovska, Nevenka (2011). Academic Branch Libraries in Changing Times. Oxford, U.K.: Chandos Pub. ISBN 978-1-78063-270-4. OCLC 1047817835.

External links

- Darnestown Civic Association

- Montgomery County Historical Society

- The Origins of Darnestown Historical Marker Database

- C&O Canal Trust - Montgomery County

- Darnestown Online features information about history, government, and links to nearby businesses and organizations.