Sensor fish

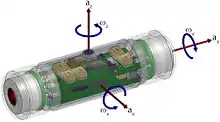

A sensor fish is a small, plastic tubular device containing sensors. It is designed to record information such as the physical stresses that a fish experiences while navigating currents from dam turbines.[1]

Description

Created by the US Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL), the tubular device is 9 cm (3.5 in) long, 2.5 cm (0.98 in) in diameter, and weighs 42 grams (1.5 ounces). It is roughly the same size as a juvenile salmon. The sensor fish has neutral buoyancy allowing it to remain underwater. Inside are sensors and a lithium-ion battery. Taking 2,048 measurements each second, it is able to record five minutes of turbulence, pressure, and acceleration, saving the data to flash memory. It records a maximum of 1.2 MPa (174 pounds per square inch) of external pressure, up to 200 gs of acceleration, temperatures ranging from -40 to 127 °C (-40 and +260 degrees F), and rotational velocity of up to 2,000 degrees per second.

Construction

The sensor fish is built manually at the Bio-Acoustics & Flow Laboratory within the PNNL. It receives funding from the Electric Power Research Institute and the US Department of Energy's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy.

Specifications

The following are the specifications as stated by the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory:[2]

- Power: rechargeable 3.7-volt lithium-ion battery

- Length: ~90 mm

- Diameter: ~25 mm

- Mass: ~42.1g

- Cost: $1,200 each

- Gyroscope: Model ITG-3200, InvenSense Inc.[3]

- Orientation: Model LSM303DLHC eCompass module made by STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland[3]

- Usage: Kaplan turbine; Francis turbine; small hydropower structures; pumped storage hydroelectric facilities

- Memory: ~5 minutes of data with flash memory

- Speed: 2,048 measurements per second

- Pressure: Model MS5412-BM, Measurement Specialties, Inc., made in Hampton, Virginia capable of 174 pounds per square inch of pressure

- Acceleration: Model ADXL377 accelerometer, Analog Devices, Inc.[3]

- Rotational velocity: 2,000 degrees per second

- Temperature range: -40 to +125 degrees Celsius using model TC1046 by Microchip Technology Inc.

- Buoyancy: neutral

- Other features:

- There is a device that releases two, small weights after a certain period of time causing the device to come to the surface for retrieval.

- Four LED lights for retrieval and diagnostics that flash orange, yellow and green

Purpose

Data collected from the sensor fish is used to help create new designs for dam turbines. Aging dams require retrofits and upgrades, and considerations about the impact on fish can be taken into account.

The sensor fish was initially designed to examine the effects of the most common kind of turbine in the Columbia River Basin, the Kaplan turbine. Most of the tests were carried out at the Ice Harbor Dam, a 100-foot-high structure. Inside the turbine of that dam, the pressure changes experienced are the same as moving from sea level to the peak of Mount Everest in an instant.[4]

In 2015, the sensor fish will evaluate a dam in Southeast Asia's Mekong River, irrigation structures in Australia, a conventional dam as well as three small hydro installations within the United States.[5]

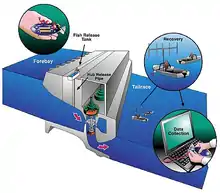

Data acquisition process

The fish sensor is deposited into the fish release tank at the top of the dam. There, it begins recording data as it travels down through the hub release pipe. It then enters and passes through the turbine. From there, it is flushed into the tailrace and is retrieved by boat.

The device is then placed into a docking station where it begins to recharge its battery and awaits transfer of the data it has gathered. The docking station sends the data to a laptop computer over USB using software developed by PNNL. The software can convert the raw, binary data into CSV format, enabling scientists to more easily plot the data.[3]

Earlier version

The first version was developed in the late 1990s and was called the "Flubber Fish".[6][7] It was created to increase the survival rate of salmon during their journey through the Columbia River Basin's dams. It was clear, rubber-coated, and looked like a fish.[8]

Future design

The second generation model will be able to accommodate other hydraulic structures and turbines. It has improved sensors for detecting pressure, better accelerometers, and better gyroscopes which detect rotational velocity. Within the device is a radio transmitter. Also, there is a device that releases two weights after a specific period of time. This allows the sensor fish to come to the surface for retrieval.

References

- "Sensor Fish show how hydroelectric dams will affect salmon". twwtn.com.

- "PNNL: News - Synthetic fish measures wild ride through dams". pnnl.gov.

- Z. D. Deng-J. Lu-M. J. Myjak-J. J. Martinez-C. Tian-S. J. Morris-T. J. Carlson-D. Zhou-H. Hou (2014). "Design and implementation of a new autonomous sensor fish to support advanced hydropower development". Review of Scientific Instruments. 85 (11): 115001. Bibcode:2014RScI...85k5001D. doi:10.1063/1.4900543. PMID 25430138.

- Michael Cooney (5 November 2014). "The Internet of fishy things". Network World.

- "Electronic 'Fish' Helps Us Understand the Trials of Salmon Migration". Nature World News. 6 November 2014.

- http://www.pnl.gov/main/publications/external/technical_reports/PNNL-15708.pdf

- "Synthetic fish measures wild ride through dams".

- "PNNL: Breakthroughs Magazine - Fall 2000: Special Report - Sensor fish make a splash". pnnl.gov.

External links

- Design and implementation of a new autonomous sensor fish to support advanced hydropower development, Z. D. Deng, J. Lu, M. J. Myjak, J. J. Martinez, C. Tian, S. J. Morris, T. J. Carlson, D. Zhou and H. Hou

- Technical report: Characterization of Fish Passage Conditions through the Fish Weir and Turbine Unit 1 at Foster Dam, Oregon, Using Sensor Fish, 2012, February 2013

- Synthesis of Sensor Fish Data for Assessment of Fish Passage Conditions at Turbines, Spillways, and Bypass Facilities – Phase 1: The Dalles Dam Spillway Case Study, December 31, 2007

- Evolution of the Sensor Fish Device for Measuring Physical Conditions in Severe Hydraulic Environments, T. J. Carlson, J. P. Duncan, February 2003