Serapeum of Saqqara

The Serapeum of Saqqara was the ancient Egyptian burial place for sacred bulls of the Apis cult at Memphis. It was believed that the bulls were incarnations of the god Ptah, which would become immortal after death as Osiris-Apis. a name which evolved to Serapis (Σέραπις) in the Hellenistic period, and Userhapi (ⲟⲩⲥⲉⲣϩⲁⲡⲓ) in Coptic. It is part of the Saqqara necropolis, which includes several other animal catacombs, notably the burial vaults of the mother cows of the Apis.[1]

Entrance ramp to the burial vaults | |

Shown within Northern Egypt | |

| Location | Saqqara |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 29.874722°N 31.2125°E |

| Type | Serapeum |

| History | |

| Builder | Amenhotep III - Cleopatra |

| Founded | c. 1400 BC |

| Abandoned | c. 30 BC |

| Periods | New Kingdom - Ptolemaic Egypt |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1850–1853; 2020–present |

| Archaeologists | Auguste Mariette |

| Public access | Limited |

Over a timespan of approximately 1400 years, from the New Kingdom of Egypt to the end of the Ptolemaic Period, at least sixty Apis are attested to have been interred at the Serapeum. For the earliest burials, isolated tombs were constructed. As the cult gained importance, underground galleries were dug that connected subsequent burial chambers. Above ground, the main temple enclosure was supplemented by shrines, workshops, housing and administrative quarters.[2]

The Serapeum was closed in the beginning of the Roman period, after 30 BC. In the subsequent centuries large-scale looting took place. Many of the superstructures were dismantled, the burial vaults broken into, and most of the mummified Apis and their opulent burial goods removed.

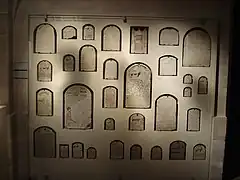

In 1850 Auguste Mariette rediscovered the Serapeum, and excavated it the following years. He found two undisturbed Apis burials, as well as thousands of objects related to centuries of cult activity. These included commemorative stela with dates relating to the life and death of the Apis and the construction of their burial vaults. This data was crucial for the establishment of an Egyptian chronology in the 19th century.

The Greater Vaults of the Serapeum, known for the large sarcophagi for the mummified bulls, are accessible to visitors.[3]

Map of Saqqara with the Avenue of Sphinxes leading to the Serapeum

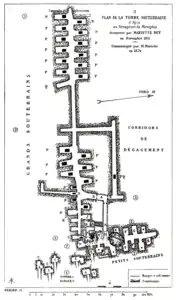

Map of Saqqara with the Avenue of Sphinxes leading to the Serapeum Plan of the burial vaults for the Apis

Plan of the burial vaults for the Apis

History

Use

The Apis cult dates back to very early times, possibly founded by pharaoh Menes, around 3,000 BC.[4]

The most ancient burials at the Serapeum, found in isolated tombs, date back to the reign of Amenhotep III of the Eighteenth Dynasty in the 14th century BC.

Khaemweset, working as an administrator during the reign of his father Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) in the Nineteenth Dynasty, ordered a tunnel with side chambers – now known as the "Lesser Vaults" – to be excavated, for the burial of the Apis bulls.

A second gallery of chambers, now called the "Greater Vaults", was commenced under Psamtik I (664–610 BC) of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty and extended during the Ptolemaic dynasty to approximately 350 m (1,150 ft) in length, 5 m (16 ft) tall and 3 m (9.8 ft) wide, along with a parallel service tunnel. From Amasis II to the end of the Ptolemaic dynasty, the sarcophagi for the Apis bulls were made from hard stone, weighing as much as 62 tonnes (68 short tons) each, including the lid.[5]

A long avenue, flanked by 370-380 sphinxes,[6] likely was built under Nectanebo I, (379/8–361/0 BC) the founder of the Thirtieth Dynasty (the last native one).

Disuse

The Serapeum was abandoned at the beginning of the Roman Period, shortly after 30 BC.[7] Strabo (64 BC–30 AD) noted that some of the Sphinxes of the dromos had been covered in sand by the wind.[8] Apis continued to be buried elsewhere in the Saqqara-Abusir region until the 3rd century AD.[9][10] Arnobius, around 300 AD, stated that the Egyptians penalized anyone who revealed the places in which Apis lay hidden.[11]

The looting of the Serapeum started at a time when hieroglyphs could still be read, as the names of the bulls were scratched out on many of the stelae. All tombs, except two, were plundered and desecrated. The bull mummies were torn to pieces, and stones were piled on the sarcophagi as a sign of contempt.[12][13]

Rediscovery

The temple was discovered by Auguste Mariette,[14] who had gone to Egypt to collect Coptic-language manuscripts, but later grew interested in the remains of the Saqqara necropolis.[15]

In 1850, Mariette found the head of one sphinx sticking out of the shifting desert dunes, cleared the sand and followed the avenue to the site. In November the following year he entered the catacombs for the first time.[8]

Unfortunately, Mariette left most of his notes unpublished. Many of them got destroyed when the Nile flooded the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities at Boulaq in 1878,[16][17] and the original diary of the excavations was borrowed by Eugène Grébaut but never returned.[18] Gaston Maspero released one volume of Le Sérapeum de Memphis based on the surviving manuscripts in 1882, a year after Mariette's death.[19]

Tourism

The Serapeum was open to visitors shortly after excavations, in the second half of the 19th century, Yet sands quickly made all parts but the Greater Vaults inaccessible.[20]

For guests, prior to the installation of electric lamps, a series of candles on wooden stands lightly illuminated the vaults, and bright magnesium light was used from time to time. When the then Prince of Wales, Edward VII visited the Serapeum, he had luncheon with his party in one of the sarcophagi.[21]

The 1992 Cairo earthquake caused cracks to appear on the tunnel walls, and the Serapeum was closed to the public.[22] In 2001 conservation work started, stabilizing the roofs and walls, which lasted until 2012.[23][24]

The majority of the Greater Vaults is accessible to tourists nowadays.

Renewed excavations

Due to the collapsed ceiling of the Lesser Vaults, Mariette left several tens of meters unexplored. In the mid 1980s, Mohamed Ibrahim Ali was the first to work there again, but he also had to give up because of the danger of collapse. In 2020 a mission began to remove the sands above the Lesser Vaults and to stabilize the bedrock, so that excavation work could be finally carried out.[25][26]

Rituals

Four events marked the career of an Apis: birth, installation, death and burial.[27] Diodorus Siculus (c. 90–30 BC) reported that the bulls were honored as gods and consecrated to Osiris, and seem to be connected to the Sed festival.[28]

Birth and installation

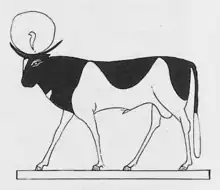

After the previous Apis had died the priests then sought out the young bull the soul of Osiris had migrated to, by identifying certain bodily marks. Herodotus reported that it needed to be black, with a three-cornered white spot on its forehead, the likeness of an eagle on its back, double tail-hairs and a knot under its tongue.[29] According to Aelian each of these marks had a specific meaning; They symbolized, for example, the stars, the shape of the crescent moon and universe, and when the Nile would rise.[30]

When the newly born Apis was found, the people stopped mourning. The calf it was kept at Nilopolis for forty days, after which a barge with a gilded stall brought it to the Temple of Ptah[31] (later Hephaestus) at Memphis. For the next forty days only women were allowed to look at the Apis, who revealed their generative parts to it. But at all other times women were forbidden in its presence.[32]

The mother-cows were said to have been made pregnant by the light of heaven or the moonlight, and could never conceive again. They were kept with the Apis at Memphis and buried in their own catacomb, the Iseum, under a kilometre (0.6 mi) north-east of the Serapeum.[33]

Death and burial

When an Apis died in the early days of the Serapeum, it was at least partially consumed and the remains conserved in a bituminous mass prior to interment.[34] In the Late Period, the time of the first large sarcophagi in the Greater Vaults, the burial ceremonies lasted for 70 days. According to the Apis Papyrus, the bulls were embalmed for 68 days, and in the last two days a series of funerary precession were held, the final one terminating in the Serapeum.[31]

The bulls were buried in splendor, reportedly 100 talents (2.6 tonnes (5,700 lb) of silver) were spent by the caretakers for the obsequies at the time of Diodorus, in the first century BC.[32]

... The sacred corpse was embalmed with spices, and the cere-cloths[Note 1] were of byssus, the fabric becoming for all the gods. His chambers were paneled with ket-wood, sycamore-wood, acadia-wood, and the best sorts of wood. Their carvings were the likeness of men in a chamber of state. A courtier of the king was appointed specially for the office of imposing a contribution for the work, on the inner country and the lower country of Egypt.[36]

...Indeed his majesty glorified him [as Horus had done to his father Osiris.] We made him (the Apis) a large sarcophagus of solid material of value, as we did before. [We made him clothes], we sent him his amulets and all his precious ornaments, they were more beautiful than any we had made so far.[37][38]

Sarcophagi

Nowadays 24 sarcophagi remain in the Greater Vaults. The oldest dates to the last great native ruler Amasis II, around 550 BC. The final was made some 500 years later, during the reign of the first Roman emperor Augustus.[39] Most are over 2 metres (6.6 ft) in width and height and almost twice as long. They weigh around 40 tonnes (88,000 lb), excluding their lids which are about half as heavy. The winches, rollers and rails found in the Serapeum might have been used to transport the stones through the narrow tunnels. The sarcophagi were lowered into their final position by removing sand the burial chambers were filled with beforehand. All surviving coffers are made out of "costly stone" (granite, basalt, diorite, etc.), whereas the older sarcophagi, which are now lost, may have been of limestone, Gunn argued.[40] Four bear inscriptions (dedications and/or spells of the pyramid texts), two of which have additional decorations.

Weight and dimensions

Linant de Bellefonds calculated one of the large sarcophagi of the Greater Vaults to have a total mass of 62 tonnes (137,000 lb) at most: 37.6 tonnes (83,000 lb) for the body and 24.4 tonnes (54,000 lb) for the lid. The stone had external dimensions of 2.32 metres (7.6 ft) in height and width, and 3.85 metres (12.6 ft) in length. Internally, the rectangular hollow was 1.73 metres (5.7 ft) high, 1.46 metres (4.8 ft) wide and 3.17 metres (10.4 ft) long. The lid had a height of 98 centimetres (3.22 ft).[5]

%252C_Box.png.webp)

%252C_LId.png.webp)

| Dimensions | Volume | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length | Width | Height | ||

| Sarcophagus | ||||

| Box | 3.85 m (12.6 ft) | 2.32 m (7.6 ft) | 2.32 m (7.6 ft) | 20.72 m3 (732 cu ft) |

| Hollow | 3.17 m (10.4 ft) | 1.46 m (4.8 ft) | 1.73 m (5.7 ft) | - 8.01 m3 (283 cu ft) |

| = 12.72 m3 (449 cu ft) | ||||

| 37.59 tonnes (82,900 lb) | ||||

| Lid | ||||

| Lid | 3.85 m (12.6 ft) | 2.32 m (7.6 ft) | 0.98 m (3.2 ft) | 8.75 m3 (309 cu ft) |

| Cut edges | 0.49 m (1.6 ft) | 0.26 m (0.85 ft) | - 0.49 m3 (17 cu ft) | |

| = 8.27 m3 (292 cu ft) | ||||

| 24.44 tonnes (53,900 lb) | ||||

Method of transport

Mariette recognized traces of rollers on the floor of the galleries, and found two wooden horizontal winches, each operated with eight levers, in one of the niches.[41] Heinrich Brugsch, visiting the Serapeum in 1853, noted that the "double-rails", on which the sarcophagi were rolled in, were still clearly preserved on the floor of the Ptolemaic service tunnel and the following passages.[42]

The floors of the burial chambers lie 2–3 metres (6.6–9.8 ft) below that of the hallway, thus the sarcophagi had to be lowered to their final positions. Mariette describes that the rooms would be filled with sand to the level of the hallway so that the sarcophagi could be moved in horizontally, then the sand would be gradually removed to gently lower them. For further protection, the ancient Egyptians cut recesses into the bedrock, about 1 metre (3.3 ft) deep, with the exact width and length of the sarcophagi. A special niche on each side allowed workers to remove the sand under the stones. Mariette found one sarcophagus that had only partially been let down into its recess, and conducted an experiment to test the aforementioned method. He was able to lower it with perfect regularity, even though its hollow was filled with rubble.[41]

According to a stela found in the Serapeum, it took 28 working days to transport one of the sarcophagi and its lid into its burial chamber, in the 37th year of Ptolemy II, circa 247 BC.[43]

[...] I constructed the aforementioned burial chamber and the ... in the year 33 (of Ptolemy II), Paopi day 4. I completed the construction in 6 months and 5 days. [...] I ordered the sarcophagus of the Apis and its lid to be moved into the burial chamber [which took 1 month and 5 days]. On 7 days no work was being done, the remainder is 28 (working) days.[43]

Inscriptions and decorations

Three of the 24 sarcophagi that remain in the Greater Vaults bear dedications by Amasis II, Cambyses II, and Khabash respectively; a fourth, inscribed with cartouches left empty, possibly dates to Ptolemy XII or Cleopatra.[44][7][45][46]

Amasis II

.jpg.webp)

A red granite sarcophagus was dedicated by Amasis II (c. 550 BC). It is very well crafted, with the exterior of the body being embellished with panelling and a spell of the pyramid texts running round close to the upper edge. The symbols were coloured green, except the white-black Apis sign.

The lid was separated from the coffer and now rests near the entrance ramp. It also bears an inscription, though no colour remains.[47][48]

[Titulary of King Amasis II] he dedicated his monument to the Living Apis, (namely) a great sarcophagus of granite. Now his Majesty found that it (a sarcophagus) had not been made in a costly stone by any king at any time. That he might be one who is given life for ever.

Cambyses II

Blocking the original entrance to the Greater Vaults is the "grey granite" sarcophagus dedicated by Cambyses II (c. 530 BC), first Persian ruler of Egypt. Only its lid is inscribed.[49]

[Titulary of Cambyses II] He made as his monument to his father Apis-Osiris a large granite sarcophagus, dedicated by the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Ms-tjw-Re, son of Re, Cambyses, endowed with all health and prosperity in perpetuity, all health, all joy, appearing as the king of Upper and Lower Egypt for eternity.

Khabash

A smaller sarcophagus stands at the entrance of an otherwise unused tunnel. A short text on its lid dates it to year 2 of Khabash (c. 336 BC), who had led a rebellion against the second Persian occupation. Its lid was found on the floor nearby. Brugsch argued that the two had never been brought together to enclose the deceased Apis. The lid was, however, put on top of the sarcophagus during past restoration works.[50]

Year 2, month Athyr, under the Majesty of King Khabash,

the friend of Apis-Osiris, of Horus "of Kakem" (a name for the locality of the Apis tombs)

Ptolemy XII or Cleopatra

Only one of the sarcophagi of the Ptolematic section is inscribed. The polished exterior is contrasted by the inscriptions and decorations which are merely scratched on and crudely formed. The cover is plain. Each side of the coffer bears a representation of a sarcophagus with a curved cornice and torus, of the Menkaure type. Panelling is found on all but the south side, which displays a house facade with a small bolted door. Along the torus, and between the double framing on each side are three lines of inscription, spells of the pyramid texts. The cartouches for the royal names were left empty. According to Gunn, because it remained to be seen under which king the Apis would die, which may point to the reign of Cleopatra and Ptolemy XIII (55-30 BC).[51] On the basis of the position of the coffer, towards the end of the Ptolemaic tunnel, it might date to year 7 of Ptolemy XII (73 BC).[7]

South side: O Apis-Osiris, someone shall stand behind thee, thy brother shall stand behind thee, he stands and shall not perish behind thee; (thou) shalt not perish, thou shalt not pass away, during the whole of eternity Apis-Osiris!

East side: O Apis-Osiris, Horus opens thine eyes for thee, that thou mayest see by them.

West side: Stand up for Horus, that he may spiritualize thee, and dispatch thee to mount up to heaven, Apis-Osiris!

Isolated Tombs

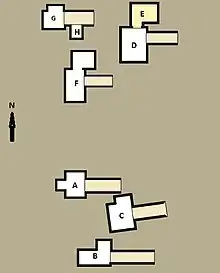

.png.webp)

.png.webp)

The oldest Apis burials in the confines of the Serapeum took place in Isolated Tombs, scattered here and there, without a regular plan. They consisted of a decorated chapel above ground with votive stela fixed to the exterior walls, dedicated to the deceased animal. In the bedrock beneath, a sloping passage led to a rectangular chamber which housed coffins with the remains of the bull, canopic jars and other burial items.

Isolated Tombs were constructed in the 18th and 19th dynasty of Egypt, during a timespan of about 160 years (c. 1390 – c. 1250 BC), between the reigns of Amenhotep III and Ramesses II. Thereafter underground galleries were dug which connected subsequent Apis burial chambers.

In this early time of the Serapeum, the bodies of the bulls seem to not have been mummified. They may have been consumed, and what remained was conserved in bitumen or resin and placed in canopic jars and nested coffins.

Six Isolated tombs for eight bulls have been identified; three burials were undisturbed (one in chamber E and two in G) when discovered by Auguste Mariette in 1852:[52][53]

- 18th Dynasty (from c. 1390 to 1290 BC)

- Isolated Tomb A – Amenhotep III

Tomb A yielded four canopic jars, magic bricks, and multiple vessels, some of which bear prince Thutmose's name. - Isolated Tomb B – Amenhotep III or IV

In tomb B canopic jars survived. - Isolated Tomb C – Tutankhamun

Tomb C contained canopic jars, pieces of the bull's wooden coffin and three glass pendants with the name of Tutankhamun. - Isolated Tomb D/E – Horemheb

Chamber D of double-tomb D/E had plastered walls with painted images of the Apis, the four sons of Horus, Isis and other figures. Only one canopic lid evaded robbery.

Chamber E was hidden by a false wall and found intact. Within a lidless stone-built sarcophagus laid a panelled wooden coffin with a vaulted lid, which contained the remains of the Apis. The bull's skull rested on a cloth-covered mass of bitumen and large bovine bones, suggesting that the bull had been consumed before burial. In the corners of the room stood canopic jars. Under the floor Mariette found a dozen large pots containing burnt bones and ashes.[54]

- Isolated Tomb A – Amenhotep III

- 19th Dynasty (from c. 1290 to 1250 BC)

- Isolated Tomb F – Seti I

Fourteen canopic vessels were also present in tomb F, along with four lids. Anything else had been robbed. - Isolated Tomb G/H – Ramesses II, years 16 & 30

Tomb G contained a pair of undisturbed burials, overseen by the fourth son of Ramesses II, Khaemweset. The two square wooden coffins were varnished black with resin, their lower halves gilt. They contained similar arrangements: Within another square nested coffin lay the lid of a third, which was anthropoid with a gilded face. Under it was a bituminous mass of fragments of small bovine bones. Unlike tomb E, no skulls were present.

The central, first burial was accompanied by four canopic jars and a gold pectoral was found within. The coffin beside it had been damaged by stones fallen from the ceiling, and contained ox-head shabtis and statuettes of royalty, carnelian amulets and other jewellery, and a large quantity of gold foil.

The walls of the tomb were decorated with paintings and gold leaf. Niches contained shabtis, two pottery jackals on pylon-shaped bases, and amulets. An additional 247 shabtis were found in cuttings in the floor. Furthermore, a life-sized gilded wood statue representing Osiris was found affixed to the wall.

On the entrance ramp, thirteen stelae were found, which revealed the dates of the deaths of the bulls.[55]

Room H was extensively robbed, but a surviving jar indicated it was a canopic room for the second bull of tomb G.[56]

- Isolated Tomb F – Seti I

- Shabtis and jewellery from coffins found in Isolated Tomb G

Lesser Vaults

New Kingdom

Working as an administrator during the reign of his father, Khaemweset, a son of Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) of the Nineteenth Dynasty, ordered that a tunnel be excavated at the site, and a catacomb of galleries – now known as the "Lesser Vaults" – be designed with side chambers to contain the sarcophagi for the mummified remains of the bulls. But for one, all chambers were found emptied of their contents except for a disarray of dedication stelae.[57][58][59]

- Gold mask and jewelry from tomb attributed to Khaemweset, in the Lesser Vaults

Shoshenq V

Two Apis died under Shoshenq V of the late 22nd Dynasty. The first one, installed in regnal year 2 of Pami, died and was buried in Shoshenq V's year 11. Its replacement in turn died and was buried in year 37. The latter's death was commemorated on several stelae, especially on the Stela of Pasenhor:[60]

This god was introduced to his father Ptah (i.e. was enthroned) in the Year 12, fourth day of month Parmouti, of King Aakheperre Shoshenq, given life. He was born in the year 11 of his majesty; he rested in his place in Tazoser (i.e. was buried) in the year 37, day 27 of month Hathor, of his majesty.[61]

Greater Vaults

.jpg.webp)

Late Period

When the Apis died around 612 BC, the Serapeum was in a state of decay. Pharaoh Psamtik I renovated the temple, and started a second underground gallery of burial chambers, now known as the "Greater Vaults".[36]

A stela, now located in the Louvre, attests the renovation of the Serapeum and its expansion:[62]

[Titulary of Psamtik I] In the year 52, under the reign of this god, information was brought to his Majesty: 'The temple of thy father Osiris-Apis, with what is therein, is in no choice condition. Look at the sacred corpses (the bulls), in what a state they are! Decay has usurped its place in their chambers.' Then his Majesty gave orders to make a renovation in his temple. It was made more beautiful than it had been before. His Majesty caused all that is due to a god to be performed for him (the deceased bull) on the day of his burial....[36]

Cambyses II

A sarcophagus dedicated by Cambyses II obstructs the original entrance way to the Greater Vaults.[62]

According to Herodotus, when Cambyses II returned to Memphis, the people were celebrating. Cambyses asked the local rulers why they had not done so on his previous arrival, they explained that the Egyptians rejoiced not because of him, but a god—the Apis—that had revealed himself. Judging this to be a lie, he put them all to death. Next, the priests were summoned before him, who gave the same account. Thus he ordered the Apis to be brought. On its arrival, Cambyses drew his dagger and stabbed the calf in the stomach and smote its thigh. He laughed: "Wretched wights, are these your gods, creatures of flesh and blood that can feel weapons of iron? That is a god worthy of the Egyptians. But for you, you shall suffer for making me your laughing-stock." The priests were punished and the festival ended. The Apis died of the leg wound and was buried without Cambyses' knowledge.[29]

Depuydt argues that the aforementioned sarcophagus was that for the predecessor of the Apis Cambyses allegedly slew, giving several reasons to corroborate Herodotus' story:[27]

- Herodotus speaks of a calf, whereas the bull attested would have been quite old.

- That the people celebrated the installation of the new calf, one of the few reasons for an Apis to appear before the people.

- That the calf was buried in secrecy, thus no sarcophagus would be expected for it in the vaults.

Darius I

Three Apis bulls were buried during the reign of Darius the Great. Since the entry way was essentially blocked by Cambyses' sarcophagus, a new makeshift entrance was cut closeby, that was used for the first two burials.

30 years later, for the burial of the third Apis, a considerably larger approach into the Greater Vaults was cut by extending the main ramp westwards beyond the old entrance stairway to a door in the bedrock, where a corridor was excavated to the south until it joined the Psamtik I gallery.

Khabash

A corridor was dug southwards, from the bottom of Darius' new entrance ramp, perhaps intended for a new set of tombs, though it was not used. One smaller sarcophagus was placed at its entrance, dating to year 2 of Khabash.[62]

Ptolemaic Egypt

| Apis | Burial Year |

|---|---|

| Ptol.1 | Ptolemy I, yr 6 |

| Ptol.2 | Ptolemy II, yr 5 |

| Ptol.3 | Ptolemy II, yr 29 |

| Ptol.4 | Ptolemy III, yr 15 |

| Ptol.5 | Ptolemy IV, yr 12 |

| Ptol.6 | Ptolemy V, yr 19 |

| Ptol.7 | Ptolemy VI, yr 17 |

| Ptol.8 | Ptolemy VIII, yr 27 |

| Ptol.9 | Ptolemy VIII, yr 52 |

| Ptol.10 | Ptolemy IX, yr 31 |

| Ptol.11 | Ptolemy XII, yr 7 |

| Ptol.12 | Cleopatra VII, yr 3 |

| Ptol.13 | Augustus (?) |

The cult continued to bury Apis bulls throughout the Ptolemaic dynasty, 305 to 30 BC. The main corridor of the Greater Vaults was enlarged and extended, ultimately totalling over 200 metres (660 ft) in length. Additionally, a "service tunnel" was dug, which bypassed earlier galleries. The votive stelae, previously fixed to the outside of the masonry that closed each burial chamber, were now put up collectively on the walls of the entrance and the new tunnel leading to the Ptolemaic section.[64]

The thirteen niches of the Ptolemaic gallery correspond to the thirteen bulls attested during this period, from the one that died in year 6 of Ptolemy I Soter to the bull Augustus refused to visit.[65] The presumably final sarcophagus was not transported all the way to its burial chamber but was abandoned in the "service tunnel".[7] The Serapeum fell into disuse shortly after and was swallowed by the sands.[8]

After this [Augustus] viewed the body of Alexander and actually touched it, whereupon, it is said, a piece of the nose was broken off. But he declined to view the remains of the Ptolemies, though the Alexandrians were extremely eager to show them, remarking, "I wished to see a king, not corpses." For this same reason he would not enter the presence of Apis, either, declaring that he was accustomed to worship gods, not cattle.[66]

— Cassius Dio, Roman History

Tunnel to the Ptolemaic section

Tunnel to the Ptolemaic section Niches in the "service tunnel" that once held stelae

Niches in the "service tunnel" that once held stelae Serapeum stelae at the Louvre

Serapeum stelae at the Louvre

Sarcophagus in the Ptolemaic section with displaced lid

Sarcophagus in the Ptolemaic section with displaced lid Roughly inscribed sarcophagus

Roughly inscribed sarcophagus Abandoned sarcophagus

Abandoned sarcophagus Lid of abandoned sarcophagus near the entrance

Lid of abandoned sarcophagus near the entrance

Superstructures

Main temple enclosure

The main temple enclosure was supplemented by shrines, workshops, housing and administrative quarters.[2]

Dromos

A dromos led from the temple of Nectanebo I to the main entrance gate of the Serapeum. It was bordered by low walls of dressed stone and flanked by a number of smaller structures.[67] Under the pavement, hundreds of bronze statuettes were found buried, representing all the deities of the Egyptian pantheon.[68]

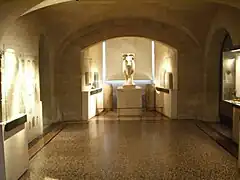

Semicircle of philosophers

.jpg.webp)

An exedra (a semicircular platform) of eleven life-sized statues of Greek poets and philosophers adjoined the dromos. The limestone sculptures that could still be identified depicted Pindar, Protagoras, Plato and Homer.[69][70]

.png.webp)

Smaller temples and shrines

In front of the precinct, a Greek Temple stood besides an Egyptian-style chapel.

Dromos during excavations in 1851. Apis statue being removed from a chapel.

Dromos during excavations in 1851. Apis statue being removed from a chapel. Apis statue now at the Louvre

Apis statue now at the Louvre The crypt of the Louvre

The crypt of the Louvre

Avenue of sphinxes

A long avenue flanked by 370-380 sphinxes was the main approach to the dromos of the Serapeum.[6] It was likely built under Nectanebo I, (379/8–361/0 BC) the founder of the Thirtieth Dynasty (the last native one).

Sphinxes of the avenue, now at the Louvre

Sphinxes of the avenue, now at the Louvre Frontal view of a sphinx of the avenue

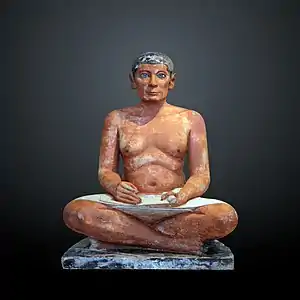

Frontal view of a sphinx of the avenue The Seated Scribe, found near the avenue

The Seated Scribe, found near the avenue

Stelae

Two bulls died under Amasis II, one in year 5, the other in year 23 of his reign. The sarcophagus of this latter still stands in situ in the Serapeum and is decorated with inscriptions and panelled reliefs. Its lid, now located at the main entrance, bears an inscription on the upper side.[48] The life of the second is documented on a stela, which was found fixed on the masonry wall that once sealed the burial chamber:[71][72]

.jpg.webp)

Year 23, month Pachons, day 15, under the reign of King Amasis, who bestows life forever, the god was carried in peace to the good region of the West. His interment in the nether-world was accomplished, in the place which his Majesty had prepared — never had the like been done since early times — after they had fulfilled for him all that is customary, in the chambers of purification; for his Majesty bore in mind what Horus had done for his father Osiris.

He had a great sarcophagus of rose granite made for him, because his Majesty found that it had not been made in a costly stone by any king at any time. He caused curtains of woven stuffs to be made for the north and south side (of the sarcophagus). He had his talismans put therein, and all his ornaments of gold and costly precious stones. They were prepared more splendidly than ever before, for his Majesty had loved the living Apis better than any other king.

The holiness of this god went to heaven in the year 23, month Phamenoth, day 6. His birth took place in year 5, month Tehuti, day 7; his inauguration at Memphis in the month Payni day 8. The full lifetime of this god amounted to 18 years, 6 months.'This is what was done for him by Aahmes-se-Nit, who bestows pure life forever'

A stela, dedicated to the first Apis that died in year 4 of Darius, states:[73]

Year 4, third month of the Season of the Harvest, day 13, under the majesty of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt Darius, endowed with life [as] Ra [forever...], this god was led in [peace] towards the beautiful west and was left to rest in the necropolis, in his place which is the place which his majesty had made for him - we had never [done the same thing before - after having done all the ceremonies] in the embalming room. Indeed his majesty glorified him [as Horus had done to his father Osiris].

We made him (the Apis) a large sarcophagus of solid material of value, as we did before. [We made him vestments], we sent him his amulets and all his excellent ornaments, they were more beautiful than what we did before.

Indeed his majesty loved [the living Apis] more than any king. The majesty of his god ascended to heaven in the year 4, the first month of the Season of Harvest, [it was born on day 4], in year 5, first month of the Season of the Emergence, day 29, [under] the majesty of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt [Ms-tjw-Re]. It was [installed] in the temple of Ptah in the year[,,, The beautiful lifespan] of the god was 8 years, 3 months and 5 days.

May Darius be, for him (the Apis), [endowed with life and prosperity forever.][37]

Stelae continued to be made during the Ptolemies, but instead of affixing them to the walls that closed each burial chamber, they were put up on the walls of the entrance and "service shaft".

A tablet commemorates the making of the underground burial chamber for the third Apis to live under Ptolemy II, including how long each phase took:[43][74]

| Creation of the burial chamber for the Apis of the mother-cow Ta-ranen | Time spent | Included

Rest Days | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Months | Days | ||

| Procuring materials for the interior of the burial chamber for the living Apis: | 3 | 15 | 17 |

| Excavation and construction of the burial chamber: | 6 | 5 | 33 |

| Transport of the sarcophagus and its lid into the burial chamber: | 1 | 5 | 7 |

| Completion of the whole edifice, after work had continued for: | 2 | 9 | 12 |

In year 18, month Phamenoth, of king Ptolemy, son of Ptolemy and Arsinoe, the gods' brothers, under construction was the burial vault of the living Apis of the cow Kerka, in Apis-year 3, for the living Apis in the Apieum.[75]

In year [...] month of Epip, day 2, of king Ptolemy, son of Ptolemy, in year 12 of the Apis of the cow Ta-ranni, which appeared in the city Teminhor, the burial vault was under construction for the Apis of the cow Ta-ranni, for the living Apis of the cow Ta-ranni in the Apieum.[76]

See also

Notes

- Waxed strips of fabric used for embalming[35]

References

- Dodson 2005, pp. 89–91.

- Marković 2017, p. 152.

- "Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities - Serapeum". egymonuments.gov.eg. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- Dodson 2005, p. 72.

- Mariette 1882, p. 113.

- Mariette 1882, p. 75.

- Dodson 2005, p. 88.

- Dodson 2000.

- Boutantin 2014.

- Marković 2018, p. 197.

- Arnobius. Seven Books against the Heathen. Vol. VI.

- Mariette 1856, p. 9.

- Brugsch 1855, p. 32.

- Málek 1983.

- Adès 2007, p. 274.

- Fagan, Brian (2003). Archaeologists: Explorers of the Human Past. Oxford University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-19-802807-9.

- "Cairo, Bulaq Museum".

- Marković 2014, p. 137.

- Mariette 1882.

- Ebers 1879, p. 181.

- Pollard 1896, pp. 152–153.

- Marković 2014, p. 138.

- Hamdy, Gehan (2021). "Stabilization of the Ancient Serapeum at Saqqara—Strengthening Proposals Using Advanced Composite Materials". Cities' Identity Through Architecture and Arts. Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation. pp. 15–24. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-14869-0_2. ISBN 978-3-030-14868-3. S2CID 229460576.

- "Egypt reopens historic Serapeum of Saqqara".

- "Louvre Museum - Resumption of excavations at Saqqara" (in French). 7 March 2022.

- Rondot, Vincent. "Musée du Louvre: La reprise des fouilles du Louvre au Serapeum de Saqqara" [The resumption of the excavations of the Louvre at the Serapeum of Saqqara.]. YouTube (in French).

- Depuydt 1995.

- Dodson 2005, p. 74.

- Herodotus (1920). "28-29". Histories. Vol. III.

- Aelian. "10". Characteristics Of Animals (De Natura Animalium). Vol. XI.

- Marković 2017, p. 145.

- Diodorus 1985, pp. 27–28, 109–114.

- Dodson 2005, p. 89.

- Dodson 2005, p. 77.

- "Cerecloth, Encyclopedia Britannica". britannica.com.

- Brugsch 1891, pp. 424–425.

- Posener 1936, pp. 36–41.

- "Lourve: Darius I Stela". 521.

- Dodson 2005, pp. 84–91.

- Gunn 1926b, p. 94.

- Mariette 1882, pp. 80–83.

- Brugsch 1855, p. 31.

- Brugsch 1884, p. 112.

- Mariette 1890, p. 119.

- Gunn 1926a.

- Gunn 1926b.

- Gunn 1926a, pp. 82–84.

- Gunn 1926b, p. 93.

- Posener 1936, pp. 35–36.

- Brugsch 1891, p. 429.

- Gunn 1926b, pp. 87–91.

- Dodson 1995, pp. 76–79.

- Mariette 1882, p. 60.

- Mariette 1882, p. 130.

- Mariette 1857, pp. 13–14.

- Dodson 2005, pp. 76–79.

- Mathieson et al. 1997.

- Mathieson et al. 1999.

- Dodson 2005.

- Kitchen 1996, §§ 84–5; Table 20.

- Breasted 1906, § 791.

- Dodson 2005, p. 85.

- Dodson 2005, p. 91.

- Dodson 2005, p. 86.

- Cassius Dio. "16.5". Roman History. Vol. 51.

- Cassius Dio. "16.5". Roman History. Vol. 51.

- Lauer 1976, p. 24.

- Mariette 1856, pp. 7–8.

- Wilcken 1917, pp. 160–173.

- Lauer 1976, p. 23.

- Brugsch 1891, p. 426See Gunn 1926b for correction.

- "Stela of bull that was born in year 5 and died in year 23 of Amasis" (in French). 570.

- "Lourve: Darius I Stela". 521.

- Brugsch 1891, p. 427English translation slightly inaccurate.

- Brugsch 1884, p. 117.

- Brugsch 1884, p. 131.

Bibliography

- Adès, Harry (2007). A Traveller's History of Egypt. chastleton Travel. ISBN 978-1-905214-01-3.

- Boutantin, Céline (2014). "Quelques documents de la région memphite relatifs au taureau Apis" [Some documents from the Memphite Region relating to the Apis bull]. BIFAO (in French). 113: 81–110.

- Breasted, James H. (1906). Ancient Records of Egypt, volume IV: the Twentieth to the Twenty-sixth Dynasties. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Brugsch, Heinrich (1855). Reiseberichte aus Aegypten: geschrieben in den Jahren 1853 und 1854 (in German). Leipzig.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Brugsch, Heinrich (1884). "Der Apiskreis aus den Zeiten der Ptolemäer nach den hieroglyphischen und demotischen Weihinschriften des Serapeums von Memphis" [The Apis-cycle from the time of the Ptolemies according to the hieroglyphic and demotic dedicatory inscriptions of the Serapeum of Memphis]. Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde (in German). 22: 110–136. doi:10.1524/zaes.1884.22.jg.110. S2CID 202553711.

- Brugsch, Heinrich (1886). "Der Apiskreis aus den Zeiten der Ptolemäer nach den hieroglyphischen und demotischen Weihinschriften des Serapeums von Memphis (Fortsetzung)". Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde (in German). 24: 19–40.

- Brugsch, Heinrich (1891). Egypt under the pharaohs: a history derived entirely from the monuments. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Depuydt, Leo (1995). "Murder in Memphis: The Story of Cambyses's Mortal Wounding of the Apis Bull (Ca. 523 B. C. E.)". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 54 (2): 119–126. doi:10.1086/373741. JSTOR 545470. S2CID 161192454.

- Diodorus (1985). Diodorus On Egypt. Translated by Murphy, Edwin. McFarland. ISBN 9780899501475.

- Dodson, Aidan (1995). "Of Bulls & Princes, the early years of the Serapeum at Sakkara". KMT. 6 (1): 18–32.

- Dodson, Aidan (2000). "The Eighteenth-Century Discovery of the Serapeum". KMT. 11 (3): 48–53.

- Dodson, Aidan (2005). "Bull Cults". Divine Creatures: Animal Mummies in Ancient Egypt. pp. 72–102. doi:10.5743/cairo/9789774248580.003.0004. ISBN 9789774248580.

- Ebers, Georg (1879). Ägypten in Bild und Wort: dargestellt von unseren ersten Künstlern (in German). Vol. 1. Stuttgart, Leipzig. pp. 177–182. doi:10.11588/DIGLIT.4991.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gunn, Battiscombe (1926a). "The Inscribed Sarcophagi in the Serapeum". Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte. Vol. 26. Le Caire, Imprimerie de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. pp. 82–91.

- Gunn, Battiscombe (1926b). "Two Misunderstood Serapeum Inscriptions". Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte. Vol. 26. Le Caire, Imprimerie de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. pp. 92–94.

- Kitchen, Kenneth A. (1996). The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 BC). Warminster: Aris & Phillips Limited. ISBN 0-85668-298-5.

- Lauer, Jean-Philippe (1976). "The Serapeum and Mariette's First Discoveries". Saqqara: The Royal Cemetery of Memphis: Excavations and Discoveries since 1850. Scribner. pp. 21–28, 33-49 (Fig. 1-14). ISBN 9780684145518.

- Málek, Jaromir (1983). "Who Was the First to Identify the Saqqara Serapeum?". Chronique d'Égypte. 58 (115–116): 65–72. doi:10.1484/J.CDE.2.308620.

- Malinine; Posener; Vercoutter (1968). Catalogue des Stèles du Sérapéum de Memphis (in French). Éditions des Musées nationaux.

- Mariette, Auguste (1856). Choix de monuments et de dessins découverts ou exécutés pendant le déblaiement du Sérapéum de Memphis [Selection of monuments and drawings discovered or executed during the clearing of the Serapeum of Memphis] (in French).

- Mariette, Auguste (1857). Le Sérapéum de Memphis (in French).

- Mariette, Auguste (1882). Maspero, Gaston (ed.). Le Sérapéum de Memphis (in French). Vol. 1. doi:10.11588/DIGLIT.4183.

- Mariette, Auguste (1890). Dickerman, Lysander (ed.). The monuments of Upper Egypt. Translated by Mariette, Alphonse.

- Marković, Nenad (2014). "The Cult of the Sacred Bull Apis: History Of Study". A History of Research Into Ancient Egyptian Culture in Southeast Europe. Archaeopress Publishing. pp. 135–144. ISBN 9781784910914.

- Marković, Nenad (2017). "The Majesty of Apis has Gone to Heaven: Burial of the Apis Bull in the Sacred Landscape of Memphis during the Late Period (664‒332 BCE)". Burial and Mortuary Practices in Late Period And Greaco-Roman Egypt. Budapest: Museum of Fine Arts. pp. 143–154.

- Marković, Nenad (2018). "Changes in Urban and Sacred Landscapes of Memphis in the Third to the Fourth Centuries ad and the Eclipse of the Divine Apis Bulls". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 104 (2): 195–204. doi:10.1177/0307513319856863. S2CID 202523841.

- Mathieson; Bettles; Clarke; Duhig; Ikram; Maguire; Quie; Tavares (1997). "The National Museums of Scotland Saqqara survey project 1993-1995". Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 83: 17–53. doi:10.1177/030751339708300103. S2CID 163675977.

- Mathieson; Bettles; Dittmer; Reader (1999). "The National Museums of Scotland Saqqara survey project 1990-1998". Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 85 (1): 21–43. doi:10.1177/030751339908500103. S2CID 193585077.

- Pollard, Joseph (1896). "Sakkarah". The land of the monuments: notes of Egyptian travel. London. pp. 145–156.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Posener, Georges (1936). La première domination Perse En Égypte (in French). Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale.

- Wilcken, Ulrich (1917). "Die griechischen Denkmäler vom Dromos des Serapeums von Memphis" [The Greek monuments of the dromos of the Serapeum of Memphis]. Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts (in German). Vol. 32. Deutsches Archäologisches Institut. pp. 149–203. doi:10.11588/diglit.44518.11.

- Thijs, Ad (2018). "The Ramesside Section of the Serapeum". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 47 (3): 293–318.