Severn and Wye Railway

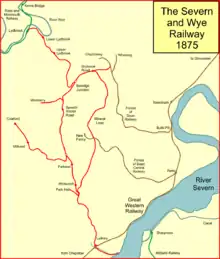

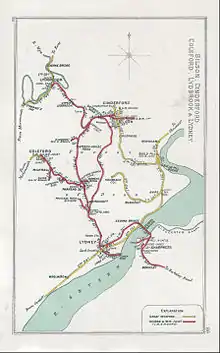

The Severn and Wye Railway began as an early tramroad network established in the Forest of Dean to facilitate the carriage of minerals to watercourses for onward conveyance. It was based on Lydney, where a small harbour was constructed, and opened its line to Parkend in 1810. It was progressively extended northwards, and a second line, the Mineral Loop was opened to connect newly opened mineral workings.

A section of the Severn and Wye Railway, now in use as a cycle and footpath. | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Locale | West Gloucestershire |

| Dates of operation | 1810–1977 |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge from 1872 |

| Previous gauge | 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) from 1810 to 1868 7 ft 1⁄4 in (2,140 mm) from 1868 to 1872 |

To facilitate transfer of traffic to the neighbouring South Wales Railway main line, the Severn and Wye Railway network was converted from a plateway to a locomotive-worked broad gauge edge railway, and then to a standard gauge railway. Extensions were made to Lydbrook, Cinderford and Coleford.

The company's finances were dependent on the mineral industry of the Forest of Dean, and in 1879 economic difficulties caused it to amalgamate with the Severn Bridge Railway. In fact this resulted in a worsening of the situation, and the combined company sold its business to the Great Western Railway and the Midland Railway jointly.

Further disappointing financial performance led to most of the passenger operation being discontinued in 1929, and after World War II inexorable decline in mineral extraction resulted in progressive closure of the network. None of the Severn and Wye Railway system is in commercial railway use today, but a heritage railway is active at Lydney.

Before railways

The Forest of Dean had been a centre of mineral extraction for centuries. A coal and iron ore industry had been carried on by freeminers, who had certain statutory rights to regulate their own affairs. Stone quarrying was also undertaken in the Forest. In the 18th and 19th centuries the timber of the Forest became an important resource for the construction of ships for the Royal Navy, creating tension with the miners, who required timber for supports in their mine workings.

Roads in the Forest were poor, and transport of heavy materials was a constant difficulty. The established rights of the miners made the deployment of capital for large-scale development very difficult, and the interests of the Royal Navy also militated against modernisation. This led to high costs, and the mining activity suffered from the competition of other locations.[1]

Early tramway proposals

In 1801 interested parties met at Ross-on-Wye and received a report from Benjamin Outram, indicating how lines of tramway might be constructed linking both Lydbrook and Lydney to the watercourses of the River Severn and the River Wye; the heavy minerals were to be transported onward to market by river and coastal shipping. The idea gained support, but it encountered fierce opposition too and the scheme foundered.

In 1806 the engineer John Rennie surveyed and proposed a route, subsequently developed with branches into a network, of tramways in the Forest, but his schemes too ended without definite action being taken.[1]

Lydney and Lydbrook Railway

The pressure to build some form of transport was unabated, and at length the Lydney and Lydbrook Railway (often rendered as Lydney and Lidbrook Railway)[2] was authorised by Act of Parliament on 10 June 1809.[3][4]

In fact it was to be a plateway, in which unflanged wagon wheels were to run on L-shaped plates; the guidance was provided by the upstand of the L-profile. The authorised capital was £35,000, to build from Lydbrook to Lower Forge by way of Mierystock and Parkend. There were to be eight branches. The railway company was not to be a carrier itself, but simply to provide the tramway on which independent carriers could run their own horse-drawn wagons.

Contracts were let in August 1809 for much of the construction, and by 4 June 1810 some mineral traffic was being carried, but dissatisfaction was already being expressed at deficiencies in the workmanship of the contractor.[1]

Severn and Wye Railway

In 1810 a deviation of the main line was authorised in a further Act of Parliament (of 21 June 1810) and the opportunity was taken to change the name of the company to the more memorable Severn and Wye Railway. An extension of the authorised capital, a further £20,000, was ratified by this Act, which also authorised the making of a harbour at Lydney and a canal giving access from there to the River Severn itself.

The line was to be a plateway, with a gauge of 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm).[note 1] (The nearby Bullo Pill tramway used 4 ft (1,219 mm).[1]) The plates were 3 feet (91 cm) long and weighed 42 pounds (19 kg); they were carried on stone blocks.

Operation had started in June 1810, but weighing machines were not yet properly provided; the company's power to charge tolls required the provision of weighing machines, and in their absence no tolls could legally be levied, so that much of the traffic travelled free at first.[5]

Dissatisfaction with the quality of the contractor's work continued to be expressed, and some track needed to be relaid at an early date. A third Act of Parliament was secured on 26 June 1811 authorised a further extension of the capital, of £35,000.[5]

On 16 March 1813 a directors’ meeting was held at which it was determined to circularise the shareholders:[1]

“The water was let into the canal and basin this day, and the railways being in a state of work, the undertaking may be considered as complete.”

However the dominant purpose of the meeting was to follow:

“A considerable debt has been incurred, to liquidate which, the sum of £10,000 must be immediately raised.”

If this was an invitation for someone to make a donation, it was in vain, and a fourth Act was obtained in May 1814 authorising a further increase in capital of £30,000.

The viability of the S&WR was in doubt with decreasing volumes of traffic due to other routes in existence or planned, giving access to the Forest, and due to its own obsolescent technology, as edge railways had by now become the normal form of railway.[5]

The South Wales Railway

In 1846, the South Wales Railway was preparing to build its line from near Gloucester to south-west Wales, intersecting the Severn and Wye Railway at Lydney. The South Wales Railway was aware of the mineral potential in the Forest of Dean and proposed a branch line alongside the Severn and Wye line. The S&WR made a counterproposal to sell their concern to the South Wales Railway, but their price was high, and the South Wales Railway did not wish to pay for the sum demanded for a declining and old-fashioned plateway.

Nevertheless, the South Wales Railway naturally wished to carry traffic originating in the Forest, and in 1847 it was authorised by Parliament to take over the Forest of Dean Railway (the former Bullo Pill line) and convert it to a broad-gauge edge railway, as a branch of its own network. The S&WR had opposed this in Parliament, but were bought off when the South Wales Railway agreed to give the S&WR £15,000 to modernise their line, adding a broad gauge edge railway alongside.[2]

The South Wales Railway opened its line between Gloucester and Chepstow in 1851, but the S&WR had done nothing to convert their line, so an interchange station was built at Lydney: minerals on the horse-drawn tramway were manually transshipped to broad-gauge wagons for onward conveyance.[1][5]

Limited modernisation

This arrangement made the obsolescent technology of the S&WR more obvious, and in 1851 a man called Blackwell was asked to prepare a scheme for the conversion and modernisation of the S&WR line. However Blackwell's scheme needed the approval of the Commissioners of Woods; the Commissioners made their approval subject to conditions that the S&WR board considered unreasonable, and the proposals foundered.

Not wishing to allow their line to stagnate, the Board decided to improve their line without conversion, and obtained an Act in August 1853; the existing tramway was to be renovated and locomotives introduced; the cost was £82,000, of which £14,000 was to come from the South Wales Railway contribution already committed. The company was empowered to become carriers themselves. Locomotive use on plateways was uncertain, because the plates were not always capable of carrying the heavy wheel loads that were likely to be imposed by practical locomotives.[1] Available adhesion was also an uncertain factor. The Act also authorised a further 3+1⁄2 miles (6 km) of tramway, but these were required to have a gauge of 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm).[2]

Nonetheless, in 1860 an 0-4-0 well-tank locomotive was ordered, and it seems to have been successful, as three more were delivered in 1864, and a fifth, this time an 0-6-0, in 1865.[6]

This progress was clearly inadequate, for the line was still a 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge plateway, and transshipment at Lydney to the mainline railway was an expensive inconvenience, while other branch lines were offering, or being planned to offer, direct interchange.

However MacDermot states that after March 1865 “much of the line was relaid with ‘compound edge rails or tramplates of a peculiar character,’ doubtless akin to the Monmouthshire Railway's combined rail and tramplate.”[6]: 402

In May 1867 the Board considered a more radical proposal: conversion of the line between Lydney and Parkend and Wimberry Junction, with a new line to Lydbrook. The cost was to be £95,298. On consideration, this was seen to be beyond the means of the company, and the scheme was limited to the conversion as far as Wimberry, at an estimated cost of £33,000.[5][1][4]

This was approved, and in 1868 a Board of Trade certificate was obtained authorising further capital of £38,000. The six-wheeled locomotive was to be converted, from 3 ft 6 in to 7 ft 1⁄4 in (2,140 mm) broad gauge, at a cost of £200. A new broad-gauge locomotive was obtained as well. These arrangements were brought into use on 19 April 1869. The line was no longer simply a toll line, of course, but it still did not own any rolling stock, and the Great Western Railway, successor to the South Wales Railway, provided wagons on request from consignors. In fact in March 1870 a broad-gauge brake van was ordered by the S&WR, as it was considered unsafe to continue working mineral trains without one. For two years or so, the S&WR therefore owned a single unit of rolling stock.[1][5]

The Mineral Loop

From the 1840s mining activity developed in the ridge of terrain southwest of Cinderford and traffic was being lost to the South Wales Railway's Forest of Dean branch, even though the dock facility at Bullo, to which that line led, was inferior to that at Lydney. Accordingly, the Board planned a new line, the Mineral Loop, connecting to many of the new pitheads. It would be formed by extending the mainline from Wimberry Junction, near Cannop, to Drybrook Road, near Cinderford; with the loop running from there to reconnect with the mainline at Tufts Junction, near Whitecroft.

The new line would require a level crossing where it met the broad gauge branch of the Forest of Dean Central Railway at New Fancy and a 503-yard (460 m) tunnel at Moseley Green. Initially, it would follow a fairly moderate descent, before a 1-in-40 drop down to Tufts Junction.

The authorising Act was the Severn and Wye Railway and Canal Act 1869, receiving Royal Assent on 16 July.[note 2][7][1]

The Forest of Dean Central Railway, sponsored by the Great Western Railway, had opened a mineral branch line from Awre (on the Gloucester–Chepstow line) to New Fancy Colliery in 1868.[8]

Construction of the Mineral Loop started in September 1870, but in February 1871 the Great Western Railway, as successor to the South Wales Railway, informed the S&WR of their intention to convert the gauge of their mainline to standard gauge. The S&WR decided to lay the Mineral Loop in standard gauge and provide mixed gauge on the existing broad gauge mainline from Tufts Junction down to Lydney Junction. In fact, the futility of retaining broad gauge on the mainline was realised, and it was converted to standard gauge on the weekend of 11–12 May 1872.[5][1][2]

On 22 April 1872 traffic started on the lower part of the Mineral Loop, below Crump Meadow, and it was substantially complete at the middle of May. The five broad gauge engines were converted to standard gauge, and a further engine was ordered from Avonside Engine Company.

By mid June 1872 the mainline was extended from Wimberry Junction to Drybrook Road, but in February 1873 the junction at Bilson was still awaited. In fact commissioning of the junction at Bilson was delayed until 15 September 1873, and the through east–west iron ore traffic which had been foreseen was not started until November 1875, probably due to difficulties in agreeing rates.[5][1]

The Lydbrook Line

Forest iron ore was in demand at iron works in South Wales, and the Lydbrook branch was conceived to allow a more direct route to iron works at the Heads of the Valleys, in particular at Ebbw Vale and Dowlais. The line was to connect at Lydbrook Junction with the Ross and Monmouth Railway, then being planned. The S&WR Lydbrook branch was authorised on 12 May 1870.[5] There was to be a triangular junction at Lydbrook enabling direct running towards Ross-on-Wye, but this was never built.

The Ross and Monmouth Railway opened for traffic on 3 August 1873; it was worked by the GWR from the outset.[5][9][1]

Like most of the S&WR lines it was steeply graded, descending at 1 in 58 from Mierystock to Lydbrook Junction. Lydbrook viaduct was to have three spans, two outer spans of 120 feet (37 m) and a centre span of 150 feet (46 m).

The line opened for goods traffic on 26 August 1874. Passenger operation started on 23 September 1875.[5][9][1][2]

The junction with the main part of the S&WR was at Serridge, on the line from Bilson to Drybrook, which opened in June 1872 as part of the mineral loop. It faced towards Bilson.[10]

Controlling loaded mineral trains at the junction was difficult; they generally had to reverse there, and there was no siding facility on the main line, and the gradients were steep. Pope and Karau explain the procedure:

On arrival at Serridge the train would stop on the running line and, when the wagons were secured, the locomotive would run round to the rear of the train to collect the brake van. It would then run round the brake van using the third loop siding and put it onto the opposite end of the train. The locomotive would then run round again to couple to the opposite end of the train which was thus reformed for the reverse direction to Lydney. The difficult part of the operation was to propel the train onto the main line sufficiently clear of the junction points and fouling bar to enable the signalman to change them before the momentum of the ascending loaded wagons was lost and they rolled back down the gradient, forcing the loco back down the bank, hopefully on its way to Lydney. This was a difficult task for all concerned and co-ordination was vital. The manoeuvre began by hauling the train back up the Lydbrook branch to Speculation Curve in order to get a run at the opposing gradient on the main line. The driver then held the regulator wide open and stormed back down the branch, propelling the wagons for all he was worth past the sidings and onto the 1 in 40 bank on the main line. This must have been quite a spectacle. As their van passed the signal box the two guards jumped off ready to pin down the wagon brakes to help hold the train on the gradient, and, the very instant the loco was clear of the points, the vigilant signalman set the road for Lydney.[9]

The Coleford branch

On 18 July 1872, parliamentary authorisation was received for the Coleford branch, leaving the old main line at Coleford Junction, at Parkend. The Coleford Railway, sponsored by the Great Western Railway, was authorised in the same session of Parliament, to build from near Monmouth to Parkend, and a clause in the authorising Act stipulated that if the S&WR failed to reach the important Easter Iron Mine at Milkwall within two years, the Coleford Railway was authorised to extend its line to it; this was an outcome the S&WR wished to avoid at all costs. The Act required a joint station and end-on connection at Coleford, although that was never made.[9][1]

The Coleford line was steeply graded, following the course of the old Milkwall tramway; the gradient was 1 in 31 falling from Milkwall to Coleford Junction, and its 3 mi 58 ch (5.99 km) extent was opened on 19 July 1875 to goods traffic; passenger opening followed on 9 December 1875[9][1][2] The junction near Parkend faced away from Lydney, so that through running from Coleford to Lydney involved a reversal there.[5][1]

The extensive sidings at Coleford Junction were completed by the previous April. The reversal was necessary for branch trains from Lydney and in practice ‘down’ goods trains left traffic at the junction for marshalling and collection by the Coleford branch engine.[10]

Coleford GWR station (the Coleford Railway station on the line from Monmouth) opened to passengers on 1 September 1883. The GWR cancelled published goods traffic rates between the S&WR station at GWR stations at once. No junction was made between the two lines, but in 1885 a connection within the sidings was made "temporarily", enabling transfer of goods wagons.[10]

The GWR Coleford branch from Wyesham Junction closed after 31 December 1916, but 71 chains (1.43 km) from Coleford to Whitecliff was retained to serve the quarry there. Access was via the transfer siding and involved four reversals, until 1951 when the siding was realigned.[9]

The Oakwood branch

This branch started as a 71-chain-long (1.43 km) broad-gauge siding to Tufts Loading Bank. It was extended along the former tramroad to Parkhill Level in 1874 and to Dyke's (or Whitecroft) Level in 1876. A further extension was made to Parkgutter in 1890–91.[1]

Passenger services on the S&WR

The S&WR Act of 1872 also authorised passenger operation on the line.[4] The S&WR was slow to implement this but in May 1875 stations were ready at Lydney Junction, Lydney Town, Whitecroft, Parkend, Speech House Road, Drybrook Road, and (possibly) Upper Lydbrook, and on the Coleford branch at Milkwall and Coleford. (Passenger excursions had previously been run, with the passengers conveyed in goods vehicles.)[9][1]

However the inspection by Col. F. M. Rich of the Board of Trade was disappointing; this was necessary to permit passenger operation, but permission was refused. A number of signalling alterations were required, chiefly facing point locks and signal repeaters; in addition, the company had no passenger rolling stock yet.

A reinspection on 13 August also resulted in refusal, but passenger operation was at last started on 23 September 1875. The service ran from Lydney to Lydbrook, with Upper Lydbrook, Lower Lydbrook, Lydbrook Junction added to the list of main line stations.[5]

The early passenger service consisted of two trains a day throughout from Lydney to Lydbrook and two from Lydney to Coleford. There were a number of short workings as well. This service was progressively reduced and by 1879 there was only one train a day from Lydney to Lydbrook and Lydney to Coleford, again with some short workings.

The Coleford branch connection faced away from Lydney. Northbound trains from Lydney usually comprised five or six carriages, the rear two of which formed the Coleford portion. On arrival at the junction these were detached and, after the Cinderford portion had continued on its way with two others from Coleford, the Coleford branch engine backed onto them.

The public joined branch trains at Parkend, but the workmen from David & Sant's nearby stoneworks were able to buy tickets from Coleford Junction signal box and board the train from a special platform at the junction. By the early 1890s the S&WR were issuing permits for this which enabled the workmen to travel to Milkwall and Coleford at a concessionary fare of 3d. It is not clear when this practice was established, but by June 1895 the platform had fallen into a dilapidated condition and had been removed. The workmen consequently trespassed on the line and climbed into the train while it was being divided.[10]

Drybrook Road served as the station for Cinderford, and as the latter was one of the more important communities in the Forest, this was clearly unsatisfactory. Extension to Cinderford itself would have involved passenger trains negotiating the flat crossing of the Trafalgar Colliery Company's tramway, and the Board of Trade had evidently indicated that this would not be permitted without proper signalling safeguards.

To avoid that expense, the S&WR constructed a "drop platform" 1⁄2 mile (0.8 km) beyond Drybrook Road, alongside the Bilson branch connection. This was approved as a temporary measure, although the location was on a steep gradient. Bilson Platform opened in September 1876. The permanent arrangement was to be a new Cinderford station further on, and this was finally opened on 29 September 1878, replacing Bilson Platform.

When passenger services were introduced in 1875 Lydbrook trains from Lydney were not allowed to reverse at Serridge, so they had to continue to Drybrook Road and reverse there. When the passenger services were extended to Cinderford (the Bilson Road station) the return journey past the junction was considerably longer.[10]

The travel writer A. O. Cooke described the working:[11]

From Speech House Road station we pass through Drybrook Road and reach Cinderford. Thence, after several bustling manoeuvres on the part of the little engine, we travel back to Drybrook Road and past Trafalgar Colliery. At Serridge Junction the train, hitherto running south-west now leaves the Speech House line and bends sharply round by Speculation Colliery, heading due north towards Upper Lydbrook.

A platform was provided at Serridge in 1878 for the use of the keeper at Serridge Lodge. Because of the difficult climb to Drybrook Road only down trains called, after the guard had been notified, but it seems it was little used and last appeared in Bradshaw in October 1879. The platform was situated on the up side close to where a forest ride crossed the line.[9]

Quick gives more detail: Serridge Platform, Speech House: In timetable from July 1877 to October 1879; Saturdays only, one way only. A note in the timetable stated that passengers for Lydbrook could alight here on informing the guard at Speech House Road; it looks as if they had to buy a ticket to Lydbrook but could get off here if more convenient.[12]

The Severn Bridge Railway

A railway had long been contemplated crossing the River Severn in the vicinity of Lydney, and on 18 July 1872 the authorising Act of the Severn Bridge Railway was passed. The railway company was to build a bridge 4,162 feet (1,269 m) in length crossing the River Severn, and connecting the Midland Railway's route between Gloucester and Bristol at Berkeley Road to Lydney Junction on the S&WR. Sharpness was an important intermediate industrial and shipping location. A northwards spur at the Berkeley end would be built by the Midland Railway, giving that company direct access to the Forest network of the S&WR.

Notwithstanding its financial commitment to its own network extensions, the S&WR subscribed £25,000 to the Severn Bridge Company, and agreed to work the line when it was complete.

In 1878 the Severn Bridge Railway found that its construction far exceeded its financial resources, and it sought a financial injection from the Midland Railway and the S&WR. The Midland declined unless it was given running powers over the entire S&WR system. That proposal had been made in the past and refused by the S&WR, concerned about its relationship with its more immediate neighbour, the GWR.

Now the resolution was for the Severn Bridge Railway Company and the Severn and Wye Railway to amalgamate. Financial assistance would be provided by the Midland Railway, which would get the running powers it had previously had refused. The Severn and Wye Railway and the Severn Bridge Railway would amalgamate, but would remain independent of the larger networks. In exchange for granting the Midland Railway running powers, the S&WR would get running powers over the Midland to Nailsworth and Stroud; although these were local centres of industry, the running powers from the Forest to those places were of little value as the Midland was dominant in taking traffic to its own large network.

It was determined that the amalgamation would take place when the Severn Bridge Railway opened to traffic, and as that event drew near, an authorising Act of Parliament was obtained on 21 July 1879.

The Severn Bridge was formally opened on 17 October 1879, and S&WR trains ran as far as Berkeley Road only. The amalgamation duly took place, forming the Severn and Wye and Severn Bridge Railway Company, although internal accounts were maintained for the two constituent companies separately until 1888. (They were known as the Forest, or Wye, section, and the Bridge section respectively.) The Lydney Junction S&WR station was replaced by a new station on the curved connection leading to the Severn Bridge. Seven passenger trains crossed the bridge daily, although only two ran through to Lydbrook Junction and one to Coleford, the remainder running between Berkeley Road and Lydney Junction only.[5][1][4]

The Great Western Railway provided a new connection giving through running from the Chepstow direction onto the Severn Bridge Railway east of Lydney in 1879. The location was named Otters Pool Junction.[8][13]

Cinderford stations

By the early 1870s the developing town of Cinderford, with its neighbouring collieries and thriving ironworks, was growing in importance as an industrial centre. However, the Severn and Wye Railway was at a disadvantage in reaching Cinderford, due to the Forest of Dean Railway which ran to the west of the town and crossed its path.

When the Bilson branch opened in 1873, it was provided only to exchange traffic with the GWR. It had been authorised in 1869 as a broad gauge branch off the Mineral Loop, but was actually constructed to standard gauge. It formed an extension of the main line from Drybrook Road to a triangular junction with the GWR's Churchway branch at Laymoor to the northwest of Cinderford. Immediately to the west of the junction the railway crossed Brain's Tramway on the level; the tramway was used to convey coal from Trafalgar Colliery to interchange sidings at Bilson yard on the GWR's Forest of Dean branch.

Bilson Junction opened for traffic on 15 September 1873. In practice it was worked as part of Bilson yard. The north and south connections were used for traffic received from and passed to the GWR respectively, and through running did not normally take place.

Drybrook Road was the nearest point to Cinderford that the first passenger service of 1875 reached. The station was originally to be named Nelson Road. The Board of Trade inspecting officer required certain improvements on his inspection on 8 June 1875, and delays in providing signalling equipment frustrated the intention of opening at an early date.

Drybrook Road station was a mile and a half from Cinderford; it was the only station for this important community, as the GWR did not provide a passenger service on the Forest of Dean branch. Following complaints from local people, the company responded by approaching the Board of Trade for permission to extend the passenger service to a temporary 'drop platform' approximately 1⁄2 mile (0.8 km) nearer the town.

The halt was known as Bilson Platform; it consisted of a simple wooden platform approximately 80 feet (24 m) in length with a shelter measuring around 18 by 6 feet (5.5 by 1.8 m). It was situated at 9 mi 65 ch (15.79 km) on a 1 in 55.8 gradient. The intention was to build a permanent station at Bilson Junction itself, but the S&WR was unable to make arrangements to convey passengers across the tramway which would satisfy the Board of Trade.

Bilson Platform was opened for traffic on 1 September 1876 and was sanctioned by the Board of Trade for one year only, until a permanent station could be built and 'this exceptional method of working be done away with'. There was a satisfactory level of passenger receipts shortly after opening, and the S&WR asked the Board of Trade in September 1878 for an extension of one further year; they said that the existing arrangements had proved sufficient for the traffic and they had not constructed the new station. The Board of Trade consented to this, but warned that they were not prepared to allow their sanction to continue after this time.

This motivated the S&WR to build a station nearer the town. It was on the north spur at Bilson Junction, and was known as Cinderford; it was finally opened for public use on 5 August 1878, although not sanctioned by the Board of Trade until 29 August. The decision to site the station no closer to the town than this was almost certainly dictated by the desire on the part of the S&WR not to incur the expense of crossing the Great Western's Churchway and Drybrook branches.

The intention was to operate a one-coach passenger train to the station, but the steep gradient was considered dangerous, and the Board of Trade inspecting officer insisted on a brake van being used on the trains.[9][1]

Financial problems

During the 1870s the world price of mineral commodities fell sharply, and coupled with miners' strikes, this had the effect of severely reducing trade in the Forest, and the income of the company. The massive expansion schemes already undertaken had been financed by the directors taking large personal loans at their own liability. A share issue in 1876 flopped and a further increase in capital authorised in 1877 was coupled with serious economy measures. An attempt was made to encourage tourist traffic, and advertising of the picturesque beauty of the Forest was published.

A further miners' strike from March 1883 had a heavy adverse effect on the company's finances, preventing it from paying debenture interest, and it was forced into administration. A scheme of arrangement released the company from that situation in July 1885.

On 1 September 1886 the Great Western Railway's Severn Tunnel opened, giving the Great Western Railway a through main line route from South Wales to Bristol and the south and east. Leading up to this time there had been a lengthy wrangle between the S&WR and the GWR over through rates for mineral traffic, but the operational convenience of the Severn Tunnel route put paid to any serious competition from the Bridge route.

A further depression in the coal trade struck the company in 1888, and the company had difficulty in paying its taxes. In 1891 it was identified that the locomotive fleet was in a seriously run down condition, but the appointment of a new locomotive foreman in 1892 seems to have retrieved the situation.

Nonetheless, the depression of trade, and the now uncompetitive cost of mineral extraction in the Forest led to a low volume of the traffic on which the company was dependent, and in 1893 the company was unable to meet its obligations, and went into receivership.

Now a coal strike in Derbyshire reversed the commercial position and for a time Forest of Dean coal was at a premium, and the company struggled to carry the traffic on offer. Welcome though this was, it was obvious that the respite could only be temporary.[5][1]

Selling the company

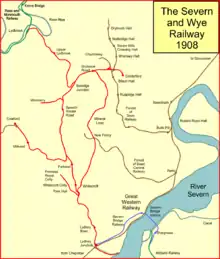

From time to time there had been consideration of selling the company to one of the neighbouring railways, the Midland Railway or the GWR. Now a definite proposal to sell to them jointly was tabled and in October 1893 the Board approved an arrangement. The sale, to include the Severn Bridge section of the merged company, was to realise a price of £477,300. The sum was about half of the capital expended in building the system, and after paying debts £131,381 was distributed among shareholders.[1] The sale went forward and on 1 July 1894 the sale was effected: the new owners were the Midland Railway and the Great Western Railway jointly.

An operating committee was established, also controlling other networks jointly owned by the two companies. The GWR was to attend to day to day matters of track and signalling, and the Midland to deal with locomotive provision and maintenance. This arrangement was altered from 1906, when the GWR attended to all maintenance matters from Coleford Junction north, and the whole of the Mineral Loop, and the Midland attended to the remainder. The Sharpness branch of the Midland Railway was also to be transferred to the new Joint Committee.[5][1][14]

A proper station for Cinderford

.jpg.webp)

The location of the Cinderford station had long been a source of complaint, and an extension into Cinderford itself was now planned; in 1894 and 1896 Parliamentary powers were sought and obtained. The new station opened on 2 July 1900, and the former unsatisfactory accommodation closed.

In 1907 the GWR decided to introduce a passenger service on the old Bullo Pill route. It was to be operated by rail motors and a new bay platform was to be provided at Newnham, on the main line, for connectional purposes. A new curve was built at Cinderford giving direct access to the S&WR station. This arrangement was implemented from 6 April 1908.[5][1][6]

At the turn of the century

Traffic was heavy on the southern core section of the old main line, and doubling of the line between Tufts Junction and Parkend was undertaken in this period, being completed in August 1898.

After 1904 changes were made to the regulation of mining in the Forest, and this enabled larger corporations to undertake more ambitious work; in particular this led to deep seams being worked in larger volumes, and in due time this led to new and considerably expanded traffic for the railway network.

From 1923

The railways of Great Britain were grouped following the Railways Act 1921; four large companies were established and the Midland Railway was a constituent of the new London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS); the Great Western Railway was augmented by the incorporation of other constituents. The new arrangement applied from the beginning of 1923; the Severn and Wye system continued to be jointly owned, now between the LMS and the GWR.[5]

Casserley points out that before grouping the network was known as the Great Western and Midland Severn and Wye Joint Railway, but after grouping was the LMS and GWR Severn and Wye Joint Railway; the reversal of precedence reflecting the capitalisation of the joint owners.[14]

The Severn and Wye network was demonstrably loss-making, and a number of economies were instituted. The most far-reaching of these was the discontinuation of passenger services north of Lydney Town; this took place after the last train on 6 July 1929.[2] The Railway Magazine reported:[15]

As from July 8 [1929], passenger train services were discontinued on the Severn & Wye Joint Railway north of Lydney Junction [sic: Lydney Town is meant] via Cinderford, to Lydbrook Junction. Motor trains continue to run between Newnham and Cinderford. Motor omnibus series have been instituted in replacement of the train services withdrawn. Trains continue to run between Berkeley Road, Lydney Junction and Lydney Town.

World War II brought considerable extra traffic to the Forest network, as it was extensively used for ammunition storage. The Mineral Loop was severed for a period to facilitate this, when from 1 April 1942 the Ministry of Works requisitioned Moseley Green Tunnel and the track was removed. By this time output from New Fancy was only 50 tons a week and the traffic was worked out via Drybrook Road.

However the severing of the line at Moseley Green was reversed, and the through line was reinstated on 29 December 1943. Nevertheless, the ordinary revenue-earning business of the Mineral Loop had declined sharply and in fact closure of the New Fancy Pit in 1944 left the Loop without any non-military use.[5]

After 1945

Mining activity declined steeply after 1945; apart from the Lydney Town passenger service, the network was almost wholly dependent on mining, so it too declined.

The network came under British Railways in 1948.

The booked goods service from Serridge Junction to Cinderford Junction was withdrawn on 25 July 1949, and the section was formally closed on 9 December 1951, although the section from the junction at Bilson to Drybrook Road was used intermittently to clear Acorn Patch depot. The closure included the whole of the mineral loop above Pillowell.[1][8]

The Lydbrook line goods business also declined steeply from 1951 and from 30 January 1956 it was closed from Mierystock to Lydbrook Junction.[1][8]

The residual passenger service on the Forest section of the Severn and Wye Railway was from Lydney Town to Berkeley Road, crossing the River Severn. On the night of 25 October 1960 an oil tank barge collided with a pier of the Severn Bridge causing a partial collapse of the bridge, and suspension of the train service over it. At first this was to be temporary, but in fact the closure of the passenger service on the Lydney side of the river became permanent.[16]

In 1960 declining mineral business resulted in closure of the old main line north of Speech House Road, and also the connection to Lydney Lower Dock.[8]

Casserley, writing in 1968 said:[14]

Practically all the lines in the Forest of Dean have been closed and abandoned, although the section from Lydney Junction to Parkend still has a daily goods [service], Mondays to Fridays in the summer of 1967, worked by a diesel hydraulic shunting locomotive of the D9500 class. The Coleford branch and beyond to Whitecliff Quarries was also in occasional use.

Heritage railway

The section between Parkend and Lydney is now restored and operating as the Dean Forest Railway.[17]

Many of the other parts of the route have been converted into cycleways.

Topography

Railways and Canals of the Forest of Dean | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Passenger stations

- Lydney Town; opened 23 September 1875; closed 26 October 1960;

- Lydney Junction; opened 23 September 1875; relocated alongside South Wales Railway station 20 October 1879; closed 26 October 1960; the former South Wales Railway part continues in use (as Lydney);

- Whitecroft; opened 23 September 1875; closed 8 July 1929;

- Parkend; opened 23 September 1875; closed 8 July 1929; known as Parkend Road in early years;

- Coleford Junction; used by workmen from 1899;

- Speech House Road; opened 23 September 1875; closed 8 July 1929;

- Serridge Platform; opened July 1877; closed October 1879; Saturdays only and in one direction only;

- Drybrook Road; opened 23 September 1875; closed 8 July 1929;

- Bilson Road Platform; opened 1 September 1876; also known as Bilson, and in local press as Cinderford; closed 5 August 1878;

- Cinderford first station; opened 5 August 1878; closed 2 July 1900;

- Cinderford second station; opened 2 July 1900; closed 3 November 1958 (in use by Newnham trains after suspension of S&WR passenger service).

- (Coleford Junction); above;

- Milkwall; opened 10 December 1875; closed 8 July 1929;

- Coleford; opened 10 December 1875; closed 8 July 1929.

- (Serridge Junction); above;

- Upper Lydbrook; opened 23 September 1875; closed 8 July 1929;

- Lower Lydbrook; opened 23 September 1875; closed 1 April 1903;

- Lydbrook; opened 4 August 1873; renamed Lydbrook Junction 1899; closed 5 January 1959.[12]

Tramway conversions

MacDermot gives the extent of conversion of the original S&WR tramways to edge railways; this is from the viewpoint of the Great Western Railway, and was written for publication in 1931.[6]

Severn and Wye Railway:

- Until 1869 this was a tramway of nearly 30 miles (48 km) in all, much of it opened in 1813. Gauge, 3 ft 8 in (1,118 mm).

At the date of sale to the GWR and Midland Railway jointly, mineral branches consisted of

- Lydney Lower Dock 1 mi 30 ch (2.21 km)

- Upper Dock 36 ch (0.72 km)

- Tufts Junction to Drybrook Road 6 mi 49 ch (10.64 km)

- Oakwood 71 ch (1.43 km)

- Parkend goods 26 ch (0.52 km)

- Parkend Royal 42 ch (0.84 km)

- Futterhill 21 ch (0.42 km)

- Sling 52 ch (1.05 km)

- Wimberry 76 ch (1.53 km)

- Drybrook Road to Cinderford Old station 67 ch (1.35 km)

- Cinderford South Loop 14 ch (0.28 km)

Tramways left unaltered:

- Bicslade 1 mi 5 ch (1.71 km)

- Howlerslade 1 mi 6 ch (1.73 km)

- Wimberry 46 ch (0.93 km)

- Total 2 mi 57 ch (4.37 km)

Gradients

The main line climbed away from Lydney Junction at 1 in 170 as far as Coleford Junction, the gradient stiffening there to 1 in 131, and after Speech House Road to 1 in 50 and 1 in 40 to a summit at Serridge Junction. It continued climbing at 1 in 40 to Drybrook Road, and then fell at the same gradient to the junctions at Bilson.

On the Lydbrook branch, the line fell from Serridge Junction to Mierystock at 1 in 507, and then descended steeply at 1 in 50 continuously, nearly as far as Lydbrook Junction.

The mineral loop climbed steeply at 1 in 40 from Tufts Junction moderating to 1 in 61 after New Fancy as far as Lightmoor, after which the line descended at 1 in 62 to Drybrook Road.

The Coleford branch climbed at 1 in 30 away from Coleford Junction as far as a point beyond Milkwall, from where it fell at 1 in 47 to the terminus.[1]

Tramway gazetteer

Baxter gives a gazetteer of the Severn and Wye and associated tramways, on page 195.[18]

See also

Notes

- 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) is given throughout Pope et al., and Paar. Casserley, page 121, gives 3 ft 8 in (1,118 mm) , as does MacDermot, volume II, page 402.

- Or 26 July according to Paar.

References

- Paar, H. W. (1963). The Severn and Wye Railway: a History of the Railways of The Forest of Dean: Part One. Dawlish: David & Charles.

- Christiansen, Rex (1981). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain. Volume 13: Thames and Severn. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-8004-4.

- Carter, E. F. (1959). An Historical Geography of the Railways of the British Isles. London: Cassell.

- Clarke, E. A. (November 1899). "The Severn and Wye Joint Railway". Railway Magazine.

- Pope, I.; How, B.; Karau, P. (1983). An Illustrated History of the Severn and Wye Railway. Volume One. Upper Bucklebury: Wild Swan Publications. ISBN 0-906-867-17-7.

- MacDermot, E. T. (1931). History of the Great Western Railway. Volume II: 1963–1921. London: Great Western Railway.

- Pope, Ian; Karau, Paul (2009). An Illustrated History of the Severn and Wye Railway. Volume 4. Didcot: Wild Swan Publications. ISBN 978-1-905184-66-8.

- Cobb, M. H. (2003). The Railways of Great Britain – A Historical Atlas. Shepperton: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 0-7110-3003-0.

- Pope, Ian; Karau, Paul (1988). An Illustrated History of the Severn and Wye Railway. Volume 3. Didcot: Wild Swan Publications. ISBN 0-906867-64-9.

- Pope, Ian; Karau, Paul (1985). An Illustrated History of the Severn and Wye Railway. Volume 2. Upper Bucklebury: Wild Swan Publications. ISBN 0-906867-28-2.

- Cooke, Arthur O. (1913). The Forest of Dean. New York: E. P. Button & Co.

- Quick, M. E. (2002). Railway Passenger Stations in England Scotland and Wales—A Chronology. The Railway and Canal Historical Society.

- Cooke, R. A. (1997). Atlas of the Great Western Railway as at 1947. Didcot: Wild Swan Publications. ISBN 1-874103-38-0.

- Casserley, H. C. (1969). Britain's Joint Lines. Shepperton: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0024-7.

- "What the Railways Are Doing". Railway Magazine. August 1929.

- Railway Magazine. December 1960.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - http://www.deanforestrailway.co.uk/section.php?xSec=23%7Cwork=Dean Dean Forest Railway

- Baxter, Bertram (1966). Stone Blocks and Iron Rails. Newton Abbot: David & Charles.