Shardlow

Shardlow is a village in Derbyshire, England about 6 miles (9.7 km) southeast of Derby and 11 miles (18 km) southwest of Nottingham. Part of the civil parish of Shardlow and Great Wilne, and the district of South Derbyshire, it is also very close to the border with Leicestershire, defined by the route of the River Trent which passes close to the south. Just across the Trent is the Castle Donington parish of North West Leicestershire.

| Shardlow | |

|---|---|

Main wharf, Shardlow | |

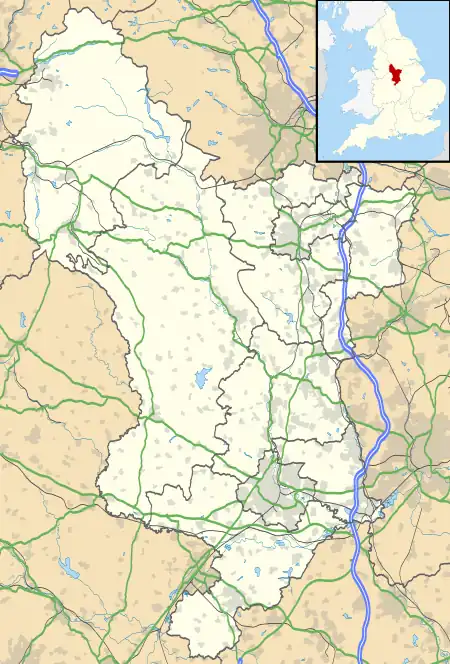

Shardlow Location within Derbyshire | |

| OS grid reference | SK437302 |

| Civil parish | |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | DERBY |

| Postcode district | DE72 |

| Police | Derbyshire |

| Fire | Derbyshire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

An important late 18th-century river port for the trans-shipment of goods to and from the River Trent to the Trent and Mersey Canal,[1] during its heyday from the 1770s to the 1840s it became referred to as "Rural Rotterdam" and "Little Liverpool".[2] Today Shardlow is considered Britain's most complete surviving example of a canal village,[2] with over 50 Grade II listed buildings and many surviving public houses within the designated Shardlow Wharf Conservation Area.[1][2]

History

Due to its location on the River Trent, which up to this point is easily navigable, there is much early evidence of human activity in the area, dating back to 1500 BC. In 1999 the 12-foot-long (3.7 m) 1300 BC Hanson Log Boat, a Bronze Age log boat was discovered at the nearby Hanson plc gravel pit. Sawn into sections so that it could be transported and conserved, the boat is now in Derby Museum and Art Gallery.[3] Five years later, a JCB in the quarry unearthed a bronze sword embedded in a vertical position in the gravel.[2] There is also a Stone Age tumulus at Lockington, an Iron Age settlement between Shardlow/Wilne and the river, and later Roman finds at Great Wilne.[1]

In 1009 Æþelræd Unræd (King Ethelred the Unready) signed a charter at the Great Council which recognised the position and boundaries of Westune.[4] The land described in that charter included the lands now known as Shardlow, Great Wilne, Church Wilne, Crich, Smalley, Morley, Weston and Aston-on-Trent. Under this charter Æþelræd gave his minister a number of rights that made him free from tax and to his own rule within the manor.[5] The manor of Shardlowe was the subject of a land deal in 1413.[6]

The village is listed as Serdelau in the Domesday Book[2] - translated as a settlement near a mound with a notch or indentation – but there have been up to 20 different spellings noted by historians.[2] The oldest surviving building today in the village is believed to be the "Dog & Duck" public house, located in the upper end of the village.[2]

Transport hub

The River Trent below Shardlow is navigable all the way to the Humber Estuary, as is the River Soar which joins 2 miles (3.2 km) further downstream. Resultantly Shardlow was always an important transport hub and trading point, as wide-beam ships and boats traded cargo commercially with the packhorse trails going across the region.[1] The tariffs charged for goods proceeding through the port enabled industrialist Leonard Fosbrooke to build Shardlow Hall,[2] and later led to skirmishes being fought locally during the English Civil War for control of the strategic transport hub.[2]

The original London to Manchester road (formerly an important turnpike road, authorised in 1738, and now the A6), passes through the village, having crossed the Trent at Cavendish Bridge, designed by the Duke of Devonshire's architect, James Paine.[2] By 1310 a rope-hauled ferry boat had replaced the last of a series of medieval bridges that crossed the Trent at what was known as Wilden Ferry. Later archaeological investigations in the Hemington Fields quarry revealed that the three wooden bridges were destroyed by floods between 1140 and 1309. During this period the unstable gravel bed of the Trent was affected by a succession of large floods, which meant that the river shifted its course significantly during this time, demolishing the bridges and an adjacent Norman mill weir.[7]

The charge to cross Paine's original 1758–1761 bridge during the years when it was subject to tolls was 2s 6d (12.5p) for carriages. It survived in service until 1947, when the Trent, swollen by a rapid thaw, swept its supports away. The British Army provided a temporary Bailey bridge, which was replaced by the present structure in 1957. Today the pediment of Paine's bridge survives as a preserved structure, with the toll charges engraved into it.[2]

Port

Due to the discovery in 1720 of heated flint being able to turn the North Staffordshire reddish-clay into a lustrous white-sheen ware, from the 18th Century volumes of cargo shipped through Shardlow accelerated, supplying product and shipping ware internationally from the Stoke-on-Trent potteries.

James Brindley built the Trent and Mersey Canal from 1766 to 1777. With a vision to connect all four of England's main rivers together – the Mersey, Trent, Severn and Thames – he created the only other comparative canal port to Shardlow in the town of Stourport-on-Severn.[2] Brindley developed his canal through Shardlow in 1770, to join the River Trent at Great Wilne 1⁄2 mile (0.80 km) further downstream at the junction with the River Derwent, which was also up to that point navigable. As a result, Shardlow quickly developed as an important UK river port, a transhipment point between the broad river barges and ships, and the canal's narrow boats. Shardlow later became the head office site of the Trent and Mersey Canal.[1]

The port outline as exists today was formed by 1816, when the 12 canal basins had been excavated.[1] But the warehouses around them were extensively reconstructed as trade developed, so that by 1820 the larger structures with the sunburst windows which exist today, had replaced the earlier buildings.[1] The wharves and associated warehouses each had designated functions, which included: coal; timber; iron; cheese; corn; and salt.[1] Other businesses which developed alongside the port included: boat builders; ropewalks; stables; offices, including the head office site of the Trent and Mersey Canal;[1] plus workers' cottages and owner's houses. Two families particularly made their fortunes: the Soresburys with rapid horse-drawn 'fly boats' on the Trent; and the Suttons with their barges and narrow boats.[1]

The importance and vitality of the port resulted in the town becoming referred to as "Rural Rotterdam" and "Little Liverpool",[2] with the population rising from 200 in 1780 to a peak of 1,306 in 1841.[1][2]

1840s-1950s

However, the subsequent arrival of the Midland Railway and associated railway branches to the area in the 1840s signalled the beginning of the end; by 1861 the population had fallen to 945, of whom 136 were in the workhouse.[2] By 1886 the port was virtually abandoned,[2] yet the end only came with the formation of the nationalised British Waterways in 1947, which quickly resulted in the removal of the formal designation of Shardlow as a port.[1]

In 1816, a large group of parishes from Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire erected a joint workhouse to the west of Shardlow, which had required the UK Parliament to approve the "Shardlow and Wilne Poor Relief Act".[8] But with an expanding number of poor people to cope with, the Union negotiated from 1834 to expand to 46 parishes encompassing a population of 29,812, ranging in population scale from Hopwell (23) to Castle Donington (3,182).[8] The "Shardlow Poor Law Union" formally came into existence on 30 March 1837, governed by an elected board of 57 guardians. The building was enlarged by Derby-based architect Henry Isaac Stevens at a cost of £2,800 in 1838–1839, to increase its capacity to 230.[8]

Shardlow and Great Wilne had been included in the parish of Aston-on-Trent until 1838.[4] But with the formation of the poor union, the combined parishes agreed to fund a parish church for the town, resulting in the opening of St James's Church designed by H.I. Stevens,[2] so that in the following year Shardlow became a parish in its own right.[2][4]

In 1905, the workhouse started its conversion to a hospital, with new buildings to its south. Post World War II under the National Health Service it formally became "The Grove" hospital,[8] which was closed in 2005 and subsequently demolished in 2007.[8]

Present

The last grain-carrying narrow boat delivered its cargo to Shardlow in the early 1950s. In 1957 the stable block which had housed over 100 towing horses was demolished, latterly followed by some of the smaller warehouses and buildings over the next twenty years. A campaign led by the newly-formed Trent & Mersey Canal Society resulted in the designation in 1975 of the Shardlow Wharf Conservation Area, which today encompasses over 50 Grade II listed buildings.[2]

During the 1970s, the men-only "Pavilion Club" flourished in the old cricket club. Then uniquely owned and operated by its gay members, it burnt down in the late 1980s. The subsequent insurance payout went into a local trust, which supported LGBT causes in the area for many years.[9]

Today, the relatively small village is considered Britain's most complete surviving example of a canal village.[2] Most of the warehouses and other port buildings have been converted to other commercial uses, or as private dwellings.[1][2]

Notable people

- Dave Brailsford, British cycling coach, was born in the village

- Charles Ingram, convicted of cheating on Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? in 2001

- Hugh Trevor Lambrick, archaeologist, historian and administrator

- W. A. Robotham of Rolls-Royce was born in the village

- Elizabeth Scott, Duchess of Buccleuch, Scottish noblewoman, was born in the village

- Robert de Shardlow (1200-c.1257), Crown official, Sheriff and judge, was born in the village and took his name from it

References

- "Brief History of the Village". Shardlow Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- "The village of Shardlow, Derbyshire". Derbyshire Life. 3 December 2010. Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- Hanson Log Boat Archived 4 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Derby.gov.uk, accessed May 2011

- Aston on Trent Conservation Area History Archived 8 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine, South Derbyshire, accessed 25 November 2008

- Charter of Æthelred, The Great Council, 1009, accessible at Derby records

- "AALT Page".

- Brown, Anthony (2008). "Late Holocene channel changes of the Middle Trent: channel response to a thousand-year flood record". Geomorphology. 39 (1–2): 69–82. doi:10.1016/S0169-555X(01)00052-6.

- "Shardlow, Derbyshire". Workhouses.org.uk. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- Peter Scott-Presland. Amiable Warriors. p. Chapter 3.