Shawl

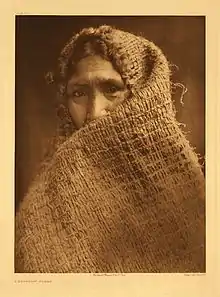

A shawl (from Persian: شال shāl,[1]) is a simple item of clothing, loosely worn over the shoulders, upper body and arms, and sometimes also over the head. It is usually a rectangular or square piece of cloth, which is often folded to make a triangle, but can also be triangular in shape. Other shapes include oblong shawls.[2] It is associated with the inhabitants of the northern Indian subcontinent—particularly Kashmir and Punjab—and Central Asia, but can be found in many other parts of the world.[3]

History

Kashmir was a pivotal point through which the wealth, knowledge, and products of ancient India passed to the world. Perhaps the most widely known woven textiles are the famed Kashmir shawls. The Kanikar, for instance, has intricately woven designs that are formalized imitations of Nature. The Chinar leaf (plane tree leaf), apple and cherry blossoms, the rose and tulip, the almond and pear, the nightingale—these are done in deep mellow tones of maroon, dark red, gold yellow and browns. Yet another type of Kashmir shawl is the Jamia Vr, which is a brocaded woollen fabric sometimes in pure wool and sometimes with a little cotton added.[4]

The floral design appears in a heavy, close embroidery-like weave in dull silk or soft pashmina (Persian, meaning "woolen"), and usually comprises small or large flowers delicately sprayed and combined; some shawls have net-like patterns with floral ensemble motifs in them. Still another type of Kashmir shawl is the double-sided Dourukha (Persian, meaning "having two faces"), a woven shawl that is so done as to produce the same effect on both sides. This is a unique piece of craftsmanship, in which a multi-coloured schematic pattern is woven all over the surface, and after the shawl is completed, the rafugar (expert embroiderer) works the outlines of the motifs in darker shades to bring into relief the beauty of design. This attractive mode of craftsmanship not only produces a shawl which is reversible because of the perfect workmanship on both sides, but it combines the crafts of both weaving and embroidery and religious beliefs expressed in different shawls.

The most expensive shawls, called shahtoosh, are made from the under-fleece of the Tibetan antelope or Chiru. These shawls are so fine that even a very tightly woven shawl can be easily pulled through a small finger ring.

The naksha, a Persian device like the Jacquard loom invented centuries later, enabled Indian weavers to create sinuous floral patterns and creeper designs in brocade to rival any painted by a brush. The Kashmir shawl that evolved from this expertise in its heyday had greater fame than any other Indian textile. Always a luxury commodity, the intricate, tapestry-woven, fine wool shawl had become a fashionable wrap for the ladies of the English and French elite by the 18th century. Supply fell short of demand and manufacturers pressed to produce more, created convincing embroidered versions of the woven shawls that could be produced in half the time. As early as 1803, Kashmiri needlework production was established to increase and hasten output of these shawls, which had been imitated in England since 1784 and even in France. By 1870, the advent of the Jacquard loom in Europe destroyed the exclusivity of the original Kashmir shawl, which began to be produced in Paisley, Scotland. Even the characteristic Kashmiri motif, the mango-shape, began to be known simply as the paisley.

The paisley motif is so ubiquitous to Indian fabrics that it is hard to realize that it is only about 250 years old. It evolved from 1600s floral and tree-of-life designs that were created in expensive, tapestry-woven Mughal textiles. The design in India originated from Persian motif called butta-jeghgha which represents a stylized cypress tree, the symbol of Iranians. Early designs depicted single plants with large flowers and thin wavy stems, small leaves and roots. As the designs became denser over time, more flowers and leaves were compacted within the shape of the tree, or issuing from vases or a pair of leaves. By the late 18th century, the archetypal curved point at the top of an elliptical outline had evolved. The elaborate paisley created on Kashmir shawls became the vogue in Europe for over a century, and it was imitations of these shawls woven in factories at Paisley, Scotland, that gave it the name paisley still commonly used in the United States and Europe. In the late 18th century and 19th century, the paisley became an important motif in a wide range of Indian textiles, perhaps because it was associated with the Mughal court. It also caught the attention of poorer and non-Muslim Indians because it resembles a mango. Cashmere Shawl is an evergreen shawl in all over india and in the world. "Rural Indians called an aam or mango a symbol of fertility".[5][6][7]

Shawls were also part of the traditional male costume in Kashmir. They were woven in extremely fine woollen twill, some such as the Orenburg shawl, were even said to be as fine as the Shatoosh. They could be in one colour only, woven in different colours (called tilikar), ornately woven or embroidered (called ameli).

Kashmiri shawls were high-fashion garments in Western Europe in the early- to mid-19th century. Paisley shawls, imitation Kashmiri shawls woven in Paisley, Renfrewshire, are the origin of the name of the traditional paisley pattern. Shawls were also manufactured in the city of Norwich, Norfolk from the late 18th century (and some two decades before Paisley) until about the 1870s.

Silk shawls with fringes, made in China, were available by the first decade of the 19th century. Ones with embroidery and fringes were available in Europe and the Americas by 1820. These were called China crêpe shawls or China shawls, and in Spain mantones de Manila because they were shipped to Spain from China via the port of Manila. The importance of these shawls in fashionable women's wardrobes declined between 1865 and 1870 in Western culture. However, they became part of folk dress in a number of places including Germany, the Near East, various parts of Latin America, and Spain where they became a part of Romani (gitana) dress especially in Andalusia and Madrid. These embroidered items were revived in the 1920s under the name of Spanish shawls. Their use as part of the costume of the lead in the opera Carmen contributed to the association of the shawls with Spain rather than China.

Some cultures incorporate shawls of various types into their national folk dress, mainly because the relatively unstructured shawls were much more commonly used in earlier times.

Usage

Shawls are used in order to keep warm, to complement a costume, and for symbolic reasons. One famous type of shawl is the tallit, worn by Jewish men during prayers and ceremonies. In Christianity, women have used shawls as a headcovering.[8] In addition to these aforementioned religious uses of shawls, they are worn for added warmth (and fashion) at outdoor or indoor evening affairs, where the temperature is warm enough for men in suits, but not for women in dresses and where a jacket might be inappropriate.[7]

Types

The Kashmir shawls

The Kashmir shawl is a type of shawl distinctive for its Kashmiri weave, and traditionally made of shahtoosh or pashmina wool. Known for its warmth, light weight and characteristic buta design, the Kashmir shawl was originally used by Mughal royalty and nobility. In the late 18th century, it arrived in Europe, where its use by Queen Victoria and Empress Joséphine popularised it as a symbol of exotic luxury and status. It became a toponym for the Kashmir region itself (as cashmere), inspiring mass-produced imitation industries in India and Europe, and popularising the buta, today known as the Paisley motif. [9]

"The shawls made in Kashmir occupy a pre-eminent place among textile products; and it is to them and to their imitations from Western looms that specific importance attaches. The Kashmir shawl is characterized by the elaboration of its design, in which the "cone" pattern is a prominent feature, and by the glowing harmony, brilliance, depth, and enduring qualities of its colours. The basis of these excellences is found in the very fine, soft, short, flossy under-wool, called pashm or pashmina, found on the shawl-goat, a variety of Capra hircus inhabiting the elevated regions of Tibet. There are several varieties of pashm, but the finest is a strict monopoly of the maharaja of Kashmir. Inferior pashm and Kerman wool — a fine soft Persian sheep's wool — are used for shawl weaving at Amritsar and other places in the Punjab, where colonies of Kashmiri weavers are established. Of shawls, apart from shape and pattern, there are only two principal classes: (1) loom-woven shawls called tiliwalla, tilikar or kani kar — sometimes woven in one piece, but more often in small segments which are sewn together with such precision that the sewing is quite imperceptible; and (2) embroidered shawls — amlikar — in which over a ground of plain pashmina is worked by needle a minute and elaborate pattern." from Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1911 [3]

Pashmina or kar Amir

The majority of the woollen fabrics of Kashmir, and particularly the best quality shawls, were and are still made of Pashm or Pashmina, which is the wool of Capra hircus, a species of the wild Asian mountain goat. Hence the shawls came to be called Pashmina. The fine fleece used for the shawls is that which grows under the rough, woolly, outer coat of the animal; that from the under-belly, which is shed on the approach of hot weather. Materials of an inferior grade were of the wool of the wild Himalayan mountain sheep or the Himalayan ibex. However, the best fleece wool is soft, silky and warm is of the wild goats, and painstakingly gathered from shrubs and rough rocks against which the animals rub off their fleece on the approach of summer. This was undoubtedly the soft fleece wool from which were made the famous and much coveted 'ring shawls' in Mughal times. Unfortunately very inferior and second rate wool taken from domesticated sheep and goats provide most of the wool used today on the looms of Kashmir.

The needle-worked Amlikar or Amli, made from Pashmina wool is a shawl embroidered almost all over with the needle on a plain woven ground. The colours most commonly seen on pashmina shawls are yellow, white, black, blue, green, purple, crimson and scarlet. The design motifs are usually formalised imitations of nature like the leaf, flower and tree designs mentioned above; they are always done in rich colours.

The embroidery stitch employed is rather like the parallel darning stitch and is rarely allowed to penetrate the entire fabric.

The outlines of the design are further touched up and emphasized with silk or woollen thread of different colours run round the finer details; the stitch used for this is at an angle overlapping darn stitch, all the stitches used are so minute and fine that individually they can be seen with the unaided eye only with difficulty. When Pashmina wool is used for the embroidery work, it is made to blend so intimately with the texture of the basic shawl material that it would be difficult to insert even a fine needle between the embroidery stitches and the basic fabric.

Do-Shalla

The Emperor Akbar was a great admirer of the shawls of Kashmir. [10] It was he who began the fashion of wearing them in duplicate, sewn back to back, so that the under surfaces of the shawls were never seen. During that time the most desired shawls were those worked in gold and silver thread or shawls with border ornamented with fringes of gold, silver and silk thread.

The Do-shala, as the name designates ("two-shawl"), are always sold in pairs, there being many varieties of them. In the Khali-matan the central field is quite plain and without any ornamentation. The Char-bagan is made up of four pieces in different colours neatly joined together; the central fluid of the shawl is embellished with a medallion of flowers. However, when the field is ornamented with flowers in the four corners we have the Kunj.

Perhaps the most characteristic of the Kashmir shawls is the one made like patchwork. The patterns are woven on the looms in long strips, about twelve to eighteen inches in length and from one half to two inches in width. These design strips, made on very simple and primitive looms, are then cut to the required lengths and very neatly and expertly hand sewn together with almost invisible stitches and finally joined by sewing to a plain central field piece. As a variation, pieces may be separately woven, cut up in various shapes of differing sizes and expertly sewn together and then further elaborated with embroidery. But there is a difference between these two types: while the patchwork loom shawls are made up from separate narrow strips, the patchwork embroidered shawls consists of a certain number of irregularly shaped pieces joined together, each one balancing the predominant colour scheme of the shawl.

Namda and Gabba

The basic material for a gubba is milled blanket dyed in plain colour. Embroidery is bold and vivid in designing and done with woollen or cotton threads. Gubbas have more of a folk flavour blankets cut and patched into geometric patterns, with limited, embroidery on joining and open space. It is more like appliqué work. Colours are bright and attractive. They are cheap and used for dewan covering or as floor covering—namdas.

Knit shawls

Triangular knit lace shawls are usually knitted from the neck down, and may or may not be shaped. In contrast, Faroese lace shawls are knitted bottom up and contain a centre back gusset. Each shawl consists of two triangular side panels, a trapezoid-shaped back gusset, an edge treatment, and usually also shoulder shaping.

Shalli

Shalli is a handwoven twill weaved shawl made of angora goat hairs.[11]

Stole

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

A stole is a woman's shawl, especially a formal shawl of expensive fabric, used around the shoulders over a party dress or ball gown. A stole is narrower than a typical shawl and of simpler construction than a cape; it is a length of a quality material, wrapped and carried about the shoulders or arms. Lighter materials such as silk and chiffon are simply finished, that is, cropped, hemmed, and bound; heavier materials such as fur and brocade are often lined as well.

A stole can also be a fur or set of furs, usually fox, worn as a stole with a suit or gown; the pelage or skin, of a single animal (head included) is generally used with street dress while for formal wear a finished length of fur using the skins of more than one animal is used; the word stole stands alone or is used in combination: fur stole, mink stole, the namesake of Dreamlander Mink Stole.

References

- Shawl.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - Bhatnagar 2005, p. 42-55.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 814.

- "Directorate of Sheep Husbandry, Kashmir Division, Government of Jammu & Kashmir". j&k sheep husbandry kashmir.nic.in. Archived from the original on 2018-01-04. Retrieved 2019-01-09.

- Bhatnagar 2005, p. 43.

- Bhatnagar 2005, pp. 42–56.

- Bhatnagar 2004, pp. 30–34.

- Zuck, RoyCheck B. (5 September 2006). Vital New Testament Issues: Examining New Testament Passages and Problems. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-59752-684-5.

- Irwin, John (1973). The kashmir shawl. London: H.M. Stationery Off. ISBN 0-11-290164-6. OCLC 3241655.

Although a garment so simple in shape and form undoubtedly has a long history in the Near East, the finest shawls of the modern era are synonymous with the name of Kashmir.

- The Art of Asian Costume: An Exhibition Presented at the University of Hawaii Art Gallery, November 13 to December 23, 1988. The Gallery. 1989. p. 34. ISBN 9780824813802.

- Wingate, Isabel Barnum (1979). Fairchild's dictionary of textiles. Internet Archive. New York : Fairchild Publications. p. 547. ISBN 978-0-87005-198-2.

Bibliography

- Bhatnagar, Parul (2004). Traditional Indian costumes & textiless. Chandigarh: abhishek. pp. 30–34, 95. ISBN 81-8247-002-1.

- Bhatnagar, Parul (2005). Decorative Design History In Indian Textiles and Costumes. Chandigarh: Abhishekh. pp. 42–56, 185. ISBN 978-81-8247-087-3. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Shawl". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 814.

Further reading

- Irwin, John (1973). The Kashmir Shawl. London: HMSO.

- Wilson, Kax (January–February 1981). "Kashmir Shawls from Europe and Asia". Art & Antiques: 69–73.

- Worth, Susannah (December 1995). "Early 20th Century Embroidered Shawls". Needle Arts. 26 (4): 38–41.

- Worth, Susannah (1986). "Embroidered China Crepe Shawls: 1800-1870". Dress. 12: 43–51. doi:10.1179/036121186803657490.