Shell money

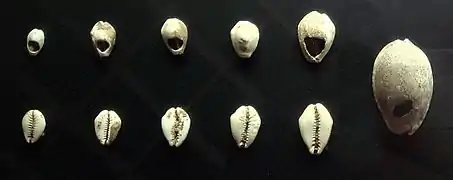

Shell money is a medium of exchange similar to coin money and other forms of commodity money, and was once commonly used in many parts of the world. Shell money usually consisted of whole or partial sea shells, often worked into beads or otherwise shaped. The use of shells in trade began as direct commodity exchange, the shells having use-value as body ornamentation. The distinction between beads as commodities and beads as money has been the subject of debate among economic anthropologists.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Economic, applied, and development anthropology |

|---|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

Shell money has appeared in the Americas, Asia, Africa and Australia. The most familiar form may be the wampum created by the Indigenous peoples of the East Coast of North America, ground beads cut from the purple part of marine bivalve shells. The shell most widely used worldwide as currency was the shell of Cypraea moneta, the money cowry. This species is most abundant in the Indian Ocean, and was collected in the Maldive Islands, in Sri Lanka, along the Malabar coast, in Borneo and on other East Indian islands, and in various parts of the African coast from Ras Hafun to Mozambique. Cowry shell money was an important part of the trade networks of Africa, South Asia, and East Asia.

North America

_(14777393065).jpg.webp)

On the east coast of North America, Indigenous peoples of the Iroquois Confederacy and Algonquian tribes, such as the Shinnecock tribe, ground beads called wampum, which were cut from the purple part of the shell of the marine bivalve Mercenaria mercenaria, more commonly known as the hard clam or quahog.[2] White beads were cut from the white part of the quahog or whelk shells. Iroquois peoples strung these shells on string in lengths, or wove them in belts.

The shell most valued by the Native American tribes of the Pacific Coast from Alaska to northwest California was Dentalium, one of several species of tusk shell or scaphopod. The tusk shell is naturally open at both ends, and can easily be strung on a thread. This shell money was valued by its length rather than the exact number of shells; the "ligua", the highest denomination in their currency, was a length of about 6 inches.

Farther south, in central California and southern California, the shell of the olive snail Olivella biplicata was used to make beads for at least 9,000 years. The small numbers recovered in older archaeological site components suggest that they were initially used as ornamentation, rather than as money.[3] Beginning shortly before 1,000 years ago, Chumash specialists on the islands of California's Santa Barbara Channel began chipping beads from olive shells in such quantities that they left meter-deep piles of manufacturing residue in their wake; the resulting circular beads were used as money throughout the area that is now southern California.[4] Starting at about AD 1500, and continuing into the late nineteenth century, the Coast Miwok, Ohlone, Patwin, Pomo, and Wappo peoples of central California used the marine bivalve Saxidomus sp. to make shell money.[5]

Africa

In Africa shell money was widely used as legal tender up until the mid 19th century. The shells of Olivella nana, the sparkling dwarf olive sea snail were harvested on Luanda Island for use as currency in the Kingdom of Kongo. They were even traded north as far as the Kingdom of Benin. In the Kongo they were called nzimbu or zimbo.[6] The shell of the large land snail, Achatina monetaria, cut into circles with an open center was also used as coin in Benguella.

In West Africa the cowrie shell was widely used, including regions far from the coast. By the early 16th century European traders were importing thousands of pounds of cowries to trade for cloth, food, wax, hides, and other goods as well as slaves. These currency flows were instrumental in the development of the powerful states of Benin, Ouidah and others along the coast.-[7]: 179–83 Between 1500 and 1875 at least 30 billion cowries were imported to the Bight of Benin, accounting for 44% of the total value of trade.[7]: 316 Around 1850 the German explorer Heinrich Barth found it fairly widespread in Kano, Kuka, Gando, and even Timbuktu. Barth relates that in Muniyoma, one of the ancient divisions of Bornu, the king's revenue was estimated at 30,000,000 shells, with every adult male being required to pay annually 1,000 shells for himself, 1,000 for every pack-ox, and 2,000 for every slave in his possession.

The shells were fastened together in strings of forty or one-hundred each, so that fifty or twenty strings represented a dollar.

As the value of the cowrie and the nzimbu was much greater in Africa than in the regions from which European traders obtained their supply, the trade was extremely lucrative. In some cases the gains are said to have been 500%. As these currency imports increased, however, inflation took hold and damaged the local economies.[7]: 201

The shells were used in the remoter parts of Africa until the early 20th century, but then gave way to modern currencies.

Asia

In China, cowries were so important that many characters relating to money or trade contain the character for cowry: 貝. Starting over three thousand years ago, cowry shells, or copies of the shells, were used as Chinese currency.[8] The Classical Chinese character radical for "money/currency", 貝, originated as a pictograph of a cowrie shell.[9]

_-_Jin_State.jpg.webp)

Cowries or kaudi were used as means of exchange in India since ancient times up to around 1830. In Bengal, where they were exchanged at a rate of 2560 to a rupee, the annual importation in early 19th century Bengal from the Maldives was valued at about 30,000 rupees. A single slave would sell for 25,000 cowries. In Orissa, India, the use of the kaudi was abolished by the British East India Company in 1805 in favor of silver. This was one of the causes of the Paik Rebellion in 1817.[10]

In Southeast Asia, when the value of the Siamese tical (baht) was about half a troy ounce of silver (about 16 grams), the value of the cowrie (Thai: เบี้ย bia) was fixed at 1⁄6400 baht.

Oceania and Australia

.jpg.webp)

In northern Australia, different shells were used by different tribes, one tribe's shell often being quite worthless in the eyes of another tribe.

In the islands north of New Guinea the shells were broken into flakes. Holes were bored through these flakes, which were then valued by the length of a threaded set on a string, as measured using the finger joints. Two shells are used by these Pacific islanders, one a cowry found on the New Guinea coast, and the other the common pearl shell, broken into flakes.

In the South Pacific Islands the species Oliva carneola was commonly used to create shell money. As late as 1882, local trade in the Solomon Islands was carried on by means of a coinage of shell beads, small shells laboriously ground down to the required size by the women. No more than were actually needed were made, and as the process was difficult, the value of the coinage was satisfactorily maintained.

Although rapidly being replaced by modern coinage, the cowry shell currency is still in use to some extent in the Solomon Islands. The shells are worked into strips of decorated cloth whose value reflects the time spent creating them.

On the Papua New Guinea island of East New Britain, shell currency is still used and can be exchanged for the Papua New Guinean kina.[11]

Middle East

In parts of West Asia, Cypraea annulus, the ring cowry, so-called because of the bright orange-colored ring on the back or upper side of the shell, was commonly used. Many specimens were found by Sir Austen Henry Layard in his excavations at Nimrud in 1845–1851.

See also

- Commodity money

- Olivella (gastropod), used as a currency by indigenous peoples of California

- Marginella, used as a currency by indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands

- Spondylus, used as a currency by indigenous peoples of the Andes and Gulf of Mexico

Notes

- Davies 1994, Mauss 1950, Trubitt 2003

- Geary, Theresa Flores. The Illustrated Bead Bible. Archived 2014-07-24 at the Wayback Machine London: Kensington Publications, 2008: 305. ISBN 978-1-4027-2353-7.

- Hughes and Milliken 2007

- Arnold and Graesch 2001

- Chagnon 1970; Milliken et al. 2007:117; Vayda 1967.

- Hogendorn, Jan; Johnson, Marion (1986). The Shell Money of the Slave Trade. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511563041. ISBN 978-0-5115-6304-1.

- Green, Toby (2020). A Fistful of Shells. UK: Penguin Books.

- Ardis Doolin (June 1985), "Money Cowries", Hawaiian Shell News, NSN #306

- References listed at Wiktionary: 貝 "貝 - Wiktionary". Archived from the original on 2017-10-17. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). - Chattopadhyay, Devasis (2020-11-27). "Cowries and the Slave Trade in Bengal". PeepulTree. Retrieved 2023-05-28.

- Sieber, Claudio (24 January 2019). "In Papua New Guinea, a Tribe Still Uses Shells as Money". www.vice.com. Retrieved 2023-04-18.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Shell-money". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 833.

- Allibert, C., 2000 "Des cauris et des hommes. Réflexion sur l'utilisation d'une monnaie-objet et ses itinéraires", in Allibert C; et Rajaonarimanana N. (eds), L'extraordinaire et le quotidien, variations anthropologiques. Paris, Karthala, pp. 57–79

- Arnold, J. E. and A.P. Graesch. 2001. The Evolution of Specialized Shellworking among the Island Chumash. In The Origins of a Pacific Coast Chiefdom: The Chumash of the Channel Islands., J.E. Arnold, ed., pp. 71–112. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- Chagnon, Napoleon A. 1970. Ecological and Adaptive Aspects of California Shell Money. Annual Reports of the University of California Archaeological Survey 12:1–25. University of California at Los Angeles.

- Davies, Glyn. 1994. A History of Money, from Ancient Times to the Present Day. University of Wales.

- Hughes, Richard D. and Randall Milliken 2007. Prehistoric Material Conveyance. In California Prehistory: Colonization, Culture, and Complexity Terry L. Jones and Kathryn A. Klar, eds. pp. 259–272. New York and London: Altamira Press. ISBN 978-0-7591-0872-1.

- Mauss, Marcel. 1950. The Gift. English translation in 1990 by W.W. North.

- Milliken, Randall, Richard T. Fitzgerald, Mark G. Hylkema, Randy Groza, Tom Origer, David G. Bieling, Alan Leventhal, Randy S. Wiberg, Andrew Gottsfield, Donna Gillete, Viviana Bellifemine, Eric Strother, Robert Cartier, and David A. Fredrickson. 2007. "Punctuated Culture Change in the San Francisco Bay Area." In California Prehistory: Colonization, Culture, and Complexity Terry L. Jones and Kathryn A. Klar, eds. pp. 99–124. New York and London: Altamira Press. ISBN 978-0-7591-0872-1.

- Trubitt, M.B.D. (2003). "The Production and Exchange of Marine Shell Prestige Goods". Journal of Archaeological Research. 11 (3): 243–277. doi:10.1023/A:1025028814962. JSTOR 41053199. S2CID 146870495.

- Vayda, Andrew. 1967. Pomo Trade Feasts. In Tribal and Peasant Economies, G. Dalton, ed., pp. 494–500. Garden City, NY: Natural History Press.

Further reading

- Pratt W. H. 1877–1880. Shell Money and Other Primitive Currencies. Proceeding Davenport Academy of Natural Sciences, volume II. page 38-46.

- Stearns, Robert E. C. (March 1869). "Shell-money". The American Naturalist. III (1): 1–5. doi:10.1086/270343.

- Stearns, R. E. C. (June 1877). "Aboriginal Shell Money". The American Naturalist. XI (6): 344–350. doi:10.1086/271901.

External links

- Cowry Shells, a trade currency Archived 2017-05-06 at the Wayback Machine, Museum of the National Bank of Belgium.

- The wealth of Africa; Money in Africa Money in Africa, The British Museum