Shi'er lü

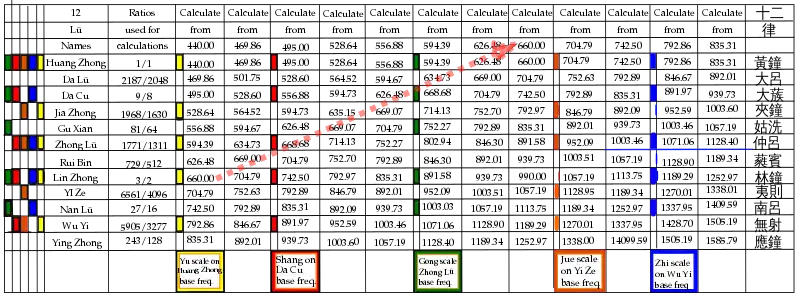

Shi'er lü (Chinese: 十二律; pinyin: shí'èr lǜ; lit. '12 pitches'; Mandarin pronunciation: [ʂɻ̩˧˥ aɚ˥˧ ly˥˩]) is a standardized gamut of twelve notes used in ancient Chinese music.[1] It is also known, rather misleadingly, as the Chinese chromatic scale; it was only one kind of chromatic scale used in ancient Chinese music. The shi'er lü uses the same intervals as the Pythagorean scale, based on 3:2 ratios (8:9, 16:27, 64:81, etc.). The gamut or its subsets were used for tuning and are preserved in bells and pipes.[2]

Unlike the Western chromatic scale, the shi'er lü was not used as a scale in its own right; it is rather a set of fundamental notes on which other scales were constructed.[3]

The first reference to "standardization of bells and pitch" dates back to around 600 BCE, while the first description of the generation of pitches dates back to around 240 CE.[3]

Note names

- 黃鐘 (黄钟) - Huáng Zhōng - tonic/unison - 1 : 1 - ⓘ

- 大呂 (大吕) - Dà Lǚ - semitone - 37 : 211 - ⓘ

- 太簇 - Tài Cù - major second - 32 : 23 - ⓘ

- 夾鐘 (夹钟) - Jiá Zhōng - minor third - 39 : 214 - ⓘ

- 姑洗 - Gū Xiǎn - major third - 34 : 26 - ⓘ

- 仲呂 (中吕) - Zhòng Lǚ - perfect fourth - 311 : 217 - ⓘ

- 蕤賓 (蕤宾) - Ruí Bīn - tritone - 36 : 29 - ⓘ

- 林鐘 (林钟) - Lín Zhōng - perfect fifth - 3 : 2 - ⓘ

- 夷則 (夷则) - Yí Zé - minor sixth - 38 : 212 - ⓘ

- 南呂 (南吕) - Nán Lǚ - major sixth - 33 : 24 - ⓘ

- 無射 (无射) - Wú Yì - minor seventh - 310 : 215 - ⓘ

- 應鐘 (应钟) - Yìng Zhōng - major seventh - 35 : 27 - ⓘ

There were 12 notes in total, which fall within the scope of one octave. Note that the mathematical method used by the ancient Chinese could never produce a true octave, as the next higher frequency in the series of frequencies produced by the Chinese system would be higher than 880 hertz.

See the article by Chen Ying-shi.[4]

See also

Further reading

- Reinisch, Richard (?). Chinesische Klassische Musik, p. 30. Books On Demand. ISBN 978-3-8423-4502-7.

Sources

- Joseph C.Y. Chen (1996). Early Chinese Work in Natural Science: A Re-examination of the Physics of Motion, Acoustics, Astronomy and Scientific Thoughts, p. 96. ISBN 962-209-385-X.

- Chen (1996), p.97.

- Needham, Joseph (1962/2004). Science and Civilization in China, Vol. IV: Physics and Physical Technology, p.170-171. ISBN 978-0-521-05802-5.

- 一种体系 两个系统 by 陈应时 (Yi zhong ti-xi, liang ge xi-tong by Chen Ying-shi of the Shanghai Conservatory), Musicology in China, 2002, Issue 4, 中国音乐学,2002,第四 期

External links

- Graham Pont. "Philosophy and Science of Music in Ancient Greece: The Predecessors of Pythagoras and their Contribution", Nexus Network Journal.