Matsutarō Shōriki

Matsutarō Shōriki (正力 松太郎, Shōriki Matsutarō, April 11, 1885 – October 9, 1969) was a Japanese journalist, media proprietor, and police officer. He owned the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper, the main mouthpiece for the military dictatorship during the war, after the war it gained Japan’s highest readership while openly distributing nationalistic and pro-American agendas.

Matsutarō Shōriki | |

|---|---|

| 正力 松太郎 | |

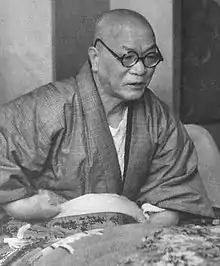

Shōriki in 1955 | |

| Born | 11 April 1885 |

| Died | 9 October 1969 (aged 84) |

| Alma mater | University of Tokyo |

| Occupation(s) | Businessman, journalist, judoka, police officer |

| Employer(s) | president of the Yomiuri Shimbun and the first president of Nippon Television Network Corporation |

| Known for | father of Japanese professional baseball "father of Japanese nuclear power" |

| Children | Tōru Shōriki |

|

Baseball career | |

| Member of the Japanese | |

| Induction | 1959 |

Investigated for war crimes, Shoriki was released without trial in 1947, and not long after began his covert career as an informant and propaganda agent for the CIA. He founded Japan's first commercial television station, Nippon Television Network Corporation in 1952. In 1955 he was elected to the House of Representatives, appointed to the House of Peers. Shoriki became head of Japan’s State Security Committee. He was the first chairman of the Japanese Atomic Energy Commission and is known as the “father of nuclear energy”.

Biography

Early life and education

Shōriki was born in Daimon, Toyama. He graduated from Tokyo Imperial University Law School, where he also was a competitive judoka in the Nanatei league. He was one of the most successful judo masters, receiving the extremely rare rank of 10th Dan after his death.[1][2]

Metropolitan Police

After graduating, he entered the Home Ministry in 1913 and joined the Metropolitan Police, rising high in the ranks.[3] Shoriki, as a report on the CIA files noted, gained notoriety by “his ruthless treatment of thought cases and by ordering raids on universities and colleges” and went on to be closely involved in the information policies of the wartime government.[4]

As a secretary of the Metropolitan Police Department, he was involved in the large-scale crackdown on the Japanese Communist Party in June 1923. In the aftermath of the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake on September 1, one of the most destructive natural disasters of the 20th century, that devastated much of Tokyo and the surrounding Kantō region, Shoriki himself was the first to consciously spread false rumors of rebellious riots by colonized Koreans through newspaper reporters.[5] As a result of these launched rumors, Korean and Chinese workers were attacked, and the military and police took the opportunity to mass murder socialists, communists, anarchists, and other dissidents during the Kantō Massacre. An estimated 6,000 to 9,000 people were slaughtered. Immediately after that, he became the Director of Police Affairs of the Metropolitan Police Department. After the Toranomon Incident, an assassination attempt on the Prince Regent Hirohito on 27 December 1923, Shoriki resigned assuming responsibility together with Superintendent of political affairs of Tokyo Metropolitan Police (警視庁, Keishichō) Kurahei Yuasa.[3] Although an amnesty cleared him of his disciplinary action, he did not return to public service.

Yomiuri Shimbun

After leaving the police Shōriki took over the presidency of the bankrupt newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun. In 1924, with the help of the powerful investor Home Minister Viscount Shinpei Goto,[3] he bought Yomiuri Shimbun. Shōriki's innovations included improved news coverage and a full-page radio program guide. The emphasis of the paper shifted to broad news coverage aimed at readers in the Tokyo area. By 1941 it had the largest circulation of any daily newspaper in the Tokyo area.

Baseball

Shōriki is known as the father of Japanese professional baseball. He organized a Japanese baseball All-Star team in 1934 that matched up against an American All-Star team. While prior Japanese all-star contingents had disbanded, Shōriki went pro with this group, which eventually became known as the Yomiuri Giants.[3]

Shōriki survived an assassination attempt by right-wing nationalists for allowing foreigners (in this case, Americans) to play baseball in Jingu Stadium.[3] He received a 16-inch-long scar from a broadsword during the assassination attempt.

Shōriki became Nippon Professional Baseball's (NPB) unofficial first commissioner in 1949. In 1950, Shōriki oversaw the realignment of the Japanese Baseball League into its present two-league structure and the establishment of the Japan Series. One goal Shōriki did not accomplish was a true world series.

World War II controversy

Shōriki was classified as a "Class A" war criminal after the Second World War, serving 21 months in the Sugamo Prison in the outskirts of Tokyo.[3] Shoriki, Yakuza boss Yoshio Kodama, his friend Ryōichi Sasakawa, a preeminent fascist political fixer, and Nobusuke Kishi, the future key man of the Liberal Democratic Party, lived in the same prison cell and were never judged. Their fraternity formed in the Sugamo Prison continued for the rest of their lives.[6]

On August 22, 1947, a recommendation was made to release Shoriki. He was suddenly released after the Americans determined that the accusations against him were mostly of an “ideological and political nature”. Shōriki later stated that his stay at "Sugamo University" was an ideal networking opportunity. Right-wingers would, with Shoriki's help, come back to rule Japan just four years after America signed a peace treaty with Japan in 1951.[3]

Nippon Television Network

In Japan, private television broadcasting began in the early 1950s thanks largely to the policies of the U.S. occupation authorities. In July 1952, just three months after the US occupation bureaucracy had formally ended, Shōriki was granted a broadcasting license for the new Nippon Television Network (NTV) by Japanese media regulators.

Nuclear power

In January 1956, Shōriki became chairman of the newly created Japanese Atomic Energy Commission, and in May of that year was appointed head of the brand-new Science and Technology Agency, both under the cabinet of Ichirō Hatoyama with strong support behind the scenes from the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency.[7] He also used his position as owner of the Yomiuri Shimbun to promote nuclear power in the popular media.[8]

In 1957, he joined the first Kishi cabinet as chairman of the National Public Safety Commission, and around the same time, the Japanese government entered into a contract to purchase 20 nuclear reactors from the United States of America. The Shoriki-LDP-CIA faction made a political decision that eventually led to the installation of 59 nuclear power plants across Japan. This corrupted relationship within the faction illustrated the root cause of the Fukushima nuclear disaster in the Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, in which the state and Tokyo Electric Power Company were held liable for the negligence of maintenance.[9]

In 2006, Tetsuo Arima, a professor specialising in media studies at Waseda University in Tokyo, published an article that proved Shōriki acted as an agent under the codenames of "podam" and "pojackpot-1" for the CIA to establish a pro-US nationwide commercial television network (NTV) and to introduce nuclear power plants using U.S. technologies across Japan. Arima's accusations were based on the findings of de-classified documents stored in the NARA in Washington, D.C.[10]

Shōriki is thus also now known as "the father of nuclear power."[3]

Death

Shōriki died October 9, 1969, in Atami, Shizuoka.

Tributes

In 1959, Shōriki was the first inductee into the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame. The Matsutaro Shoriki Award is given annually to the person who contributes the most to Japanese baseball.

The position of Chair of the Department of Asia, Oceania, and Africa at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is also named after Shōriki.[11]

Further reading

- De Lange, William (2023). A History of Japanese Journalism: State of Affairs and Affairs of State. Toyo Press. ISBN 978-94-92722-393.

- Uhlan, Edward and Dana L. Thomas. Shoriki: Miracle Man of Japan. A Biography. New York: Exposition Press, 1957. E-book at the Internet Archive.

References

- Profiles of Judo 10th Dan Holders — Judan

- John Stevens: The way of Judo, a Portrait of Jigoro Kano & his Students, Shambhala, 2013. Page 230; page 160-161

- "Matsutaro Shoriki: Japan’s Citizen Kane," The Economist (Dec 22, 2012).

- "Tessa Morris-Suzuki. The CIA and the Japanese media: A cautionary tale". 16 September 2014.

- 木村愛二. “(8-2)「朝鮮人暴動説」を新聞記者を通じて意図的に流していた正力”, www.jca.apc.org. Retrieved 25 August 2022

- Koichiro Osaka: The Imperial Ghost in the Neoliberal Machine (Figuring the CIA), e-flux Journal, Issue #100, May 2019

- "Nuclear policy was once sold by Japan's media". The Japan Times. 22 May 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- Wang, Jincao (2023-05-21). "Newspaper reports and the peaceful use of nuclear power from 1945 to 1963: an analysis of Japan's Asahi and Yomiuri Shimbun". Contemporary Japan: 1–17. doi:10.1080/18692729.2023.2214480. ISSN 1869-2729.

- Richard Krooth, Morris Edelson, Hiroshi Fukurai: Nuclear Tsunami, The Japanese Government and America’s Role in the Fukushima Disaster. Lexington Books, 2015, page 18.

- 有馬哲夫 (2006-02-16). "『日本テレビとCIA-発掘された「正力ファイル」』". 週刊新潮. ('CIA was excavated and NTV "Shoriki file"' by Tetsuo Arima)

- "Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Announces New Chair of Art of Asia, Oceania, and Africa." artdaily.org. 20 September 2008. Accessed 14 May 2009.