Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia

Shubenacadie (/ˌʃuːbəˈnækədi/ SHOO-bə-NAK-ə-dee) is a village located in Hants County, in central Nova Scotia, Canada. As of 2021, the population was 411.

Shubenacadie | |

|---|---|

Community | |

| |

Shubenacadie Shubenacadie in Nova Scotia | |

| Coordinates: 45°8′23.58″N 63°25′3.17″W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Nova Scotia |

| County | Hants County |

The name for the Mi'kmaw territory in which present-day Shubenacadie is located and the origin of its name is the Mi'kmaw word Sipekne'katik, which "place abounding in groundnuts" or "place where the wapato grows."[1][2] Historically, the Sipekne'katik region was a large stretch of territory that covered central Nova Scotia.

History

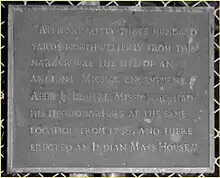

Father Louis-Pierre Thury sought to gather the Mi'kmaq of Peninsular Nova Scotia into a single settlement around Shubenacadie as early as 1699. Not until the Dummer's War between the New France-aligned Wabanaki Confederacy and English New England from 1722–1725, however, did Antoine Gaulin,[3] a Quebec-born missionary, erect a permanent mission at Shubenacadie (adjacent to Snides Lake and close to the former Residential school). He also made seasonal trips to Cape Sable, LaHave, and Mirlegueche.[4]

The Shubenacadie mission's dedication to Saint Anne speaks to a spirit of accommodation on the part of both the French and the Mi'kmaq. Anne, traditionally identified as the mother of Mary, was the grandmother of Jesus himself. The esteemed position of grandmothers in Mi'kmaw society was a point of agreement between Roman Catholicism and the Mi'kmaw worldview, and highlights the complexity and contingency of the 'conversion' process.[4]

In 1738, Abbé Jean-Louis Le Loutre arrived in October of that year at Mission Sainte-Anne, having spent the previous winter in Cape Breton learning the Mi'kmaw language with Abbé Pierre Maillard. During Dummer's War and King George's War, Mission Sainte-Anne was a sort of military base along with being a place of worship. Louis Coulon de Villiers' hardy troop passed this way on their brutal mid-winter march toward the Battle of Grand Pré in 1747, and Mi'kmaw warriors used the site as a staging point for their attacks on Halifax and Dartmouth during Father Le Loutre's War.[4] During Father Le Loutre's War, Captain Matthew Floyer arrived at the Mission on August 18, 1754 and recorded:

Half after Twelve we came to the Masshouse, which I think is the neatest in the Country, 'tis Adorned with a Fine lofty Steeple and a Weather Cock. The Parsonage House is the only Habitation here, the land is good & seems to be more so on the opposite side.

Floyer's map, which accompanied his written report, suggests the presence of three structures at the mission site.

Twelve months later, the Expulsion of the Acadians began during the French and Indian War and by October 1755, Mission Sainte-Anne appears to have been destroyed. Oral tradition says the Mi'kmaq destroyed the mission to prevent it from falling into the New Englanders possession and dumped it into Snides Lake, which was adjacent to the mission Historically-minded individuals like Henry Youle Hind and Elizabeth Frame in the late 19th century, and Douglas Ormond, F. H. Patterson, and others in the early 20th, rendered enough of this folklore into ink to save it from oblivion.

Demographics

- Shubenacadie part A

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, Shubenacadie part A had a population of 401 living in 176 of its 191 total private dwellings, a change of -45.4% from its 2016 population of 735. With a land area of 4 km2 (1.5 sq mi), it had a population density of 100.3/km2 (259.6/sq mi) in 2021.[5]

- Shubenacadie part B

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, Shubenacadie part B had a population of 10 living in 6 of its 7 total private dwellings, a change of -94.7% from its 2016 population of 187. With a land area of 2.12 km2 (0.82 sq mi), it had a population density of 4.7/km2 (12.2/sq mi) in 2021.[5]

Visitor attractions

Shubenacadie is connected to the Minas Basin by the Shubenacadie River which experiences a tidal bore on each incoming high tide; this area of Nova Scotia is recognized for having the world's highest tides. There are several companies in nearby Maitland where individuals can hire boats and guides to travel the tidal bore up the Shubenacadie River during the summer months.

The provincial Department of Natural Resources operates a helibase and forest fire fighting equipment depot in nearby Shubenacadie East. DNR also operates the Shubenacadie Wildlife Park at this property. Ducks Unlimited and DNR also operate the Greenwing Legacy Interpretive Centre on the property.[6] The wildlife park houses animals native to Nova Scotia, including black bears and moose, as well as several non-native species, including deer, and cougar. There are also several Sable Island Ponies. School programs are offered throughout the year, and interpretive programs are ongoing throughout the summer months. Shubenacadie Sam is a popular attraction around Groundhog Day when the rodent provides "projections" for the arrival of spring.

The community of Shubenacadie has a small museum called the Tinsmith Museum and Craft Shop.[7] Dating to the early 1890s, the building was used continuously as a milk can fabrication facility and hardware store until 2000. Its late owner Harry Smith left the property to the community. It converted the building to a museum. The museum features:

- A hardware store - with goods and supplies from the 1920s.

- Tinsmith shop - with all the original equipment intact from the 1890s.

- Craft shop and gift store, staffed and stocked by local Nova Scotian artists.

- Additional exhibits - veterans memorial, clothing, household goods, farm tools.

The Atlantic Motorsport Park is located in North Salem, approximately 11 kilometres northwest of Shubenacadie.[8] It is one of North America's only full-time road racing tracks that is owned and operated completely by volunteers.

Shubenacadie Residential School

Shubenacadie was the location of the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School, a Canadian residential school, that was operated from 1923 to 1967 by two Roman Catholic orders, the Sisters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul and the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate. This was the only Indian residential school in Atlantic Canada. The school building was destroyed in a fire in 1986 and today the property has been adapted for the Scotia Plastics factory.

Nora Bernard, a Mi'kmaw activist, attended the school for five years. Later in life, she was directly responsible for what became the largest class action lawsuit in Canadian history, compensation for an estimated 79,000 former students of the Canadian Indian residential school system.[9][10]

Notable residents

- Native American activist Anna Mae Aquash was born in nearby Indian Brook.

- Daniel N. Paul - Mi'kmaq elder, author, activist

- Jean-Baptiste Cope - Leader of Mi'kmaq militia

- Jean-Louis Le Loutre - Missionary Priest

- George Lang (builder)

- Shubenacadie Sam, a groundhog at the Shubenacadie Wildlife Park, gives predictions on Groundhog Day.

References

- Sable, Trudy; Francis, Bernard; Lewis, Roger J. (2012). The Language of this Land, Mi'kma'ki. Cape Breton University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-897009-49-9.

- ‘In the Micmac Indian dialect ākăde signifies a place[…]. The Shubenacadie River is called by the natives Saagaabenācăde, a place where their favourite root the sagaaban grows. The term Shubenacadie was given to the river, where such root plants were formerly very abundant. Alternatively, "Shubenacadie" is believed to translate to "I'm well in Acadia" pronounced in Chiac as "chu bien en Acadie". (Abraham Gesner, The industrial resources of Nova Scotia (Halifax, N.S.: A. & W. MacKinlay, 1849), p. 2)

- Dictionary of Canadian Biography

- Northeast Archaeological Research Archived 2012-10-11 at the Wayback Machine

- "Population and dwelling counts: Canada and designated places". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- Shubenacadie Wildlife Park

- Tinsmith museum website

- Atlantic Motorsport Park

- Halifax Daily News article on Bernard in 2006 Archived 2008-09-30 at the Wayback Machine Archived at Arnold Pizzo McKiggan

- "Foul play suspected in death". Archived from the original on 2018-10-31. Retrieved 2007-12-31.