Shunsuke Matsumoto

Shunsuke Matsumoto (松本 竣介, Matsumoto Shunsuke, 1912–1948) was a Japanese painter, who primarily painted in the Yōga ("Western painting") style.[1] Matsumoto is known for his urban landscapes. His works can be divided into two series: those depicting anonymous urban landscapes and people in cold blue tones in a montage style, and those depicting Tokyo and Yokohama landscapes in dull brown tones.[2] For a short period between 1947 and 1948, Matsumoto also painted Cubist-style works.[2]

Shunsuke Matsumoto | |

|---|---|

松本竣介 | |

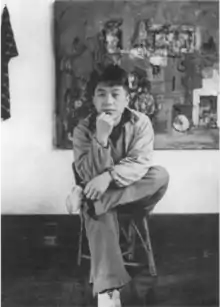

Shunsuke Matsumoto at his atelier in Shimoochiai (1940s) | |

| Born | Satō Shunsuke (俊介) April 19, 1912 |

| Died | June 8, 1948 (aged 36) |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Known for | Western painting |

| Notable work | Machi 1936 |

Biography

Early life and education in Iwate Prefecture (1912–1929)

Matsumoto was born on April 19, 1912, in Shibuya, Tokyo as Shunsuke Satō (佐藤俊介).[3] Matsumoto was the second son of father Katsumi and mother Hana, and had an elder brother, Akira, who was two years older than him.[4]: 7 Before his marriage in 1936, Matsumoto's maiden name was Satō (he took the surname Matsumoto after marrying Teiko Matsumoto 松本禎子). Matsumoto moved to Hanamaki, Iwate Prefecture, when he was two years old, following his father's participation in the apple wine brewing business, and to Morioka, Iwate Prefecture, when he was ten.[4]: 10, 14 Morioka is the hometown of his father Katsumi.[5]: 126 Matsumoto attended Iwate Normal Elementary School (岩手師範付属小学校), graduated at the top of his class in 1925, and entered Morioka Junior High School (岩手県立盛岡中学校) with the highest grades.[4]: 18 The day before the school entrance ceremony, he had a headache, but pushed himself to attend the ceremony and the next morning he contracted cerebrospinal meningitis which caused the loss of his hearing.[4]: 20–21 He was discharged from hospital in early autumn and started school in October 1925.[4]: 21 The future sculptor Yasutake Funakoshi was among his schoolmates and in the same grade.

Matsumoto’s father, Katsumi, wanted to send his son to the Military Training School, but Matsumoto himself wanted to become an engineer.[4]: 22 Since Matsumoto’s deafness cut off his path to a military career, Katsumi decided to let his son become an engineer as he wished, and bought him a camera and equipment for developing pictures.[4]: 22 Matsumoto was enthusiastic about it for a while, but soon lost interest in cameras.[4]: 22 At that time, Matsumoto’s elderly brother Akira bought a set of oil painting tools and sent them to his younger brother.[4]: 26–27 This led Matsumoto to start painting. From the summer of his second year of junior high school, Matsumoto became passionate about sketching, and in his third year he created a painting club at school.[4]: 26–27 He gradually began to aspire to become a painter.

Pacific Painting Institute and Ikebukuro Montparnasse (1929–1933)

In March 1929, Matsumoto dropped out Morioka Junior High School in his third year and moved to Tokyo. Matsumoto’s primary school teacher, Mizuhiko Sato, was working at Jiyū Gakuen, which was then located in Ikebukuro, and through his supports, Matsumoto rented a house next door to Sato's and began to live there.[4]: 30–31 From there, he began attending the Pacific Art Institute (太平洋画会研究所; later renamed the Pacific Art School 太平洋美術学校).[4]: 31 At the time, the Institute had a continuous conflict between the students and the management over tuition fees, and in the late autumn of 1930 the institute changed its name and re-started as an art school, which Matsumoto continued to attend.[4]: 33 Aimitsu, Chōzaburō Inoue, and Masao Tsuruoka also attended this institute (they stopped attending after the institute was converted to an art school), but they did not know each other at the time.[4]: 33 At the Pacific Art School, Matsumoto received training from Gorō Tsuruta.[4]: 36

At the time he was attending the Pacific Art School, Matsumoto was hugely interested in Modigliani's art and life.[4]: 44 Matsumoto formed a group called Akamame (赤荳), which is a Japanese translation of the name of a girl in the biographical novel of Modigliani, Les Montparnos, written by Georges Michel.[4]: 44 [5]: 131 With his fellow (mostly Marxists) artists at the Pacific Art School, Matsumoto co-founded a group called the Pacific Modern Art Study Group (太平洋近代藝術研究会), and published a magazine called Sen (線 meaning "Line"; the first issue was published in September 1931).[4]: 39–40 Matsumoto, however, did not agree with the Marxist theory of art and Sen was terminated after two issues.[4]: 42

In 1932, he rented an atelier with his fellow artists in Ikebukuro, where many artists lived and worked, and formed an artistic community called Ikebukuro Montparnasse.[5][4]: 45–46 At this time, he became romantically involved with a model, Masayo Iwamoto, but this caused a rift between the friends and the joint atelier was dissolved after five months.[4]: 49 During the period of the joint atelier, he underwent a conscription examination in his hometown, but was exempted from military service because of his deafness.[4]: 50 After the dissolution of the atelier, Matsumoto started living with his brother Akira.[4]: 49

Art of Life and marriage (1933–1936)

Matsumoto’s father Katsumi was originally a Christian, but converted to Nichiren Buddhism and later became a believer of the Seichō no ie.[4]: 55–56 Matsumoto’s elder brother Akira also became a believer of the Seichō no ie under the influence of his father's enthusiastic encouragement. Around 1930, Masaharu Taniguchi, the founder of the Seichō no ie, told Akira that he was going to publish an art magazine, Seimei no Geijutsu (生命の藝術; Art of Life) (first published in 1933), and Akira invited Matsumoto to take charge of its editing.[4]: 56–57 However, Matsumoto was not initially keen on this offer, and it was not until three years later in 1933 that he agreed to edit the magazine.[4]: 57 Together with Akira, Matsumoto began editing the Seimei no Geijutsu and continued until 1936. It was at this workplace that he met his future wife, Teiko Matsumoto.[4]: 59

In 1933, Matsumoto became acquainted with Aimitsu. In 1935, Matsumoto exhibited at the exhibition of the NOVA Art Association, founded by Masao Tsuruoka and others, and was immediately recommended as a full member of the association.: 83 [4] In the autumn of the same year, Matsumoto went to a museum in Ueno to show Teiko his paintings that had been selected for the Nika Exhibition for the first time, where he came into contact with the work of Hideo Noda for the first time, and was influenced for some time afterwards.[4]: 63–65, 100 The following year, in 1936, he exhibited City (Machi) at the Nika Exhibition, a work that was strongly influenced by Noda.[4]: 101 When Hideo Noda died suddenly in January 1937, Matsumoto bought a collection of Noda's works published in a limited edition of 500 copies.[4]: 102

On 3 February 1936, Matsumoto and Teiko were married in the Tokyo Kaikan in accordance with the Seichō no ie ceremony style.[4]: 67 At the beginning of the marriage, they lived in the household of Teiko’s family, but soon moved to another rented house, where they lived with their mother-in-law, Tsune, and two of Teiko's younger sisters (Yasuko and Eiko). The rented house was an elegant two-story Western-style house with an atelier.[4]: 67–68 While working as an editor of Seimei no Geijutsu (Art of Life), Matsumoto was a member of Seichō no ie. But Matsumoto became disconnected when it was converted into a religious organisation, and he wrote a letter to Taniguchi to part ways with the Seichō no ie.[4]: 71 At about the same time, his father Katsumi, his elder brother Akira, his wife Teiko and mother-in-law Tsune also left the Seichō no ie.[4]: 70–72

Miscellaneous Notes and first solo show (1936–1939)

Matsumoto stopped editing Seimei no Geijutsu (Art of Life), and in October 1936 he edited and published the first issue of the magazine Zakkichō (雑記帳; Miscellaneous Notes) by himself.[4]: 78 It was financed with the help of his brother Akira. It started with a first edition of 5,000 copies but sold very little and was reduced to a run of 3,000 copies, but it was no longer financially sustainable, and Miscellaneous Notes ended with the December 1937 issue (vol. 14).[4]: 93 A number of well-known figures contributed to the Miscellaneous Notes: among writers, Katsuichirō Kamei, Haruo Satō, Shūzō Takiguchi, Sakutarō Hagiwara, Murō Saisei, Tatsuji Miyoshi, and Yojūrō Yasuda; while among painters, in addition to the Ikebukuro Montparnasse members, Katsuzō Satomi, Seiji Tōgō, Tsuguharu Foujita and Sōtarō Yasui contributed articles and illustrations.[4]: 96

Meanwhile, his first child was born in April 1937, but died the following day due to premature birth.[4]: 86 At the beginning of 1939, a supporters' association for Matsumoto was set up to sell his paintings. Seiji Tōgō and Tamiji Kitagawa wrote letters of endorsement, but Matsumoto’s paintings did not sell well.[4]: 106 Instead, he earned a living by working as an illustrator for magazines and producing murals for beauty salons and coffee shops, which were run by his friends.[4]: 106 In July 1939 his first son Kan was born, and in the summer of 1940, Matumoto was awarded a special prize at the Nika Exhibition. In October of the same year, he held his first solo exhibition at the Nichidō Gallery in Ginza for three days.[4]: 111 He exhibited 30 works in this solo exhibition.

The Living Painter (1941)

Probably in the very end of 1940, Saburō Asō visited Matsumoto’s studio with the January 1941 issue of the art magazine Mizue.[4]: 126 The issue featured an 11-page roundtable discussion entitled “The National Defence State and Art: What Should Painters Do” (Kokubō kokka to bijutsu: Gaka wa nani o nasubeki ka). The speakers were Major Suzuki Kurazō (Army Information Section), Major Kunio Akiyama (Army Information Section), First Lieutenant Senkichirō Kuroda (Army Information Section), Takashi Kamigori (Mizue editor), and Hideo Araki (art critic).[3] None of the participants were artists. The speakers attacked the strawmen of pure art, art for art's sake, and demanded the new art that would be meaningful for the state and Japanese race.[3] Matsumoto had read this issue, and he and Asō spent a long time in Matsumoto’s studio talking secretly.[5]: 551 The details of what he and Asō were talking about at this time are unknown, as neither Asō nor Matsumoto gave details after the war.[5]: 551 After Asō’s visit, Matsumoto approached the president of Mizue with a request to write a rebuttal, and they agreed on publishing a manuscript of 20 pages.[4]: 129 The manuscript was written over the course of a month and published in the April issue of Mizue under the title "Ikiteiru gaika" (Living Painter").[3] The title is thought to have been inspired by Tatsuzō Ishikawa's banned novel Ikiteiru heitai (The Living Soldier).

After the war, Matsumoto has long been regarded as a "painter of resistance", based on this rebuttal article against the military authority in April 1941.[4]: 3 However, it is increasingly known today that he was not against the totalitarian state policy itself, and that he did produce several war propaganda posters during the war.[4]: 3

Painting Society of the New Man (1943–1945)

In the spring of 1943, Matsumoto visited Chōzaburō Inoue, who was living in Ikebukuro Montparnasse, to discuss the formation of new artist group.[4]: 139–140 Along with Inoue, Aimitsu, Masao Tsuruoka, Wasaburō Itozono, Gorō Ōno, Masaaki Terada, Saburō Asō, and others formed the Painting Society of the New Man (Shinjin Gakai; 新人画会), which held its first exhibition in April for ten days in a small gallery on the second floor of a music shop in Ginza.[4]: 149 Matsumoto exhibited five paintings. The office of the Painting Society of the New Man was set up in Matsumoto’s home. At the time, the art exhibitions were predominantly war paintings, but at the Painting Society of the New Man exhibitions, only landscapes and portraits were exhibited. Because of this, after the war, the Painting Society of the New Man was sometimes described as the only group of anti-war painters in Japan.[5]: 542 However, according to interviews with former member of the Painting Society of the New Man including Asō, Itozono, Inoue, Terada and others, there was no such anti-war statement shared among the group.[5]: 542–546

In October 1943, Matsumoto displayed three war propaganda posters in an exhibition in Iwate Prefecture.[4]: 151 In November, the Painting Society of the New Man held its second exhibition for six days in Ginza.[4]: 149 In September 1944, the third Painting Society of the New Man exhibition was held for three days at the Shiseidō Gallery.[4]: 149 From this time on, Matsumoto changed character of his name from Shunsuke (俊介) to Shunsuke (竣介).[4]: 149 In September 1944, the Cabinet Intelligence Bureau decided to ban exhibitions other than those organized or co-organized by the Bijutsu Hōkokai (美術報国会), and exhibitions by the Painting Society of the New Man were no longer possible thereafter.[4]: 152 In March 1945, when indiscriminate air raids on the Japanese mainland by the US military intensified, he evacuated his wife Teiko, his mother-in-law Tsune and his eldest son Kan to Matsue, while he himself remained in Tokyo.[4]: 152 On 10 April his first daughter Yōko was born.[4]: 153 on 25 May the Yamanote area in Tokyo was bombed and the Shimo-Ochiai area was also heavily bombed, but only the area around Matsumoto’s home escaped damage.

After the war (1945–1948)

In 1945, a two-person exhibition with Yasutake Funakoshi was held at a department store in their hometown of Morioka. In October 1945, at a time when the war responsibility discussion was raging, Matsumoto contributed an article to the Asahi Newspaper entitled “An artist's conscience” (Geijutsuka no ryōshin). The article was not accepted, but in it he argued that the theme of war painting itself had a timeless universality.[2]: 363 Around this time, Matsumoto was working with Saburō Asō and Yasutake Funakoshi on the idea of founding new art group. Matsumoto was invited to become a member by Seiji Tōgō of Second Section Society (Nika-kai), by Junkichi Mukai of Action Art Association (Kōdō bijutsu kyōkai) and by Ichirō Fukuzawa of the Art and Culture Association (Bijutsu bunka kyōkai), but he declined all of offers.[4]: 169 The following year, in January 1946, Matsumoto sent a pamphlet with an article, titled “Consult with All Japanese Artists” (Zennihon bijutsuka ni hakaru) to painters.[4]: 170 In November 1946, Matsumoto held a three-person exhibition with Saburō Asō and Yasutake Funakoshi at the Nichidō Gallery in Ginza. Around this time, Matsumoto’s rib pain and asthma began to worsen.[4]: 171 Matsumoto later joined the Free Artists' Association (Jiyū bijutsuka kyōkai) together with Saburō Asō, Masao Tsuruoka, Chōzaburō Inoue, and others, and in June 1947 exhibited at the 1st Art Group Union Exhibition (Bijutsu dantai rengōten), the 11th Free Artists' Association exhibition in July, and in October at a three-person exhibition in Gifu Prefecture with Aso and Funakoshi.[2]: 369 During the three-person exhibition in Gifu, his eldest daughter Yōko died of urinary poisoning, and in December Matsumoto himself fell ill with croup after catching a cold, but recovered in the beginning of the following year.[2]: 369

In February 1948, after the Free Artists' Association, Matsumoto told his wife Teiko of his intention to move to Paris.[4]: 177 Soon after, their second daughter Kyōko was born.[4]: 177 In March Matsumoto felt strong chest pains, but gave priority to the production of the 2nd Art Group Union Exhibition in May.[4]: 178 His health deteriorated further afterwards and he was even unable to bring the completed paintings to the exhibition venue himself, so they were brought in by his sisters-in-law and others.[2]: 224 Matsumoto was also unable to visit the exhibition.[2]: 224 On 24 May, Matsumoto’s friend Tetsurō Sawada brought him to a doctor at Keio Hospital because he had a high fever.[4]: 179 After examining him, the doctor told Matsumoto’s wife Teiko that he had tuberculosis.[4]: 179 As Matsumoto and Teiko could not afford the costs for hospitalization, he was resting at home, but his condition suddenly changed on the morning of 7 June and he died at the age of 36 on the following day, June 8, 1948, from heart failure aggravated by tuberculosis and bronchial asthma.[4]: 181 [3]

Gallery

self-portrait (1941)

self-portrait (1941) Portrait of Chuya Takahashi (1941)

Portrait of Chuya Takahashi (1941) Bridge in Y-City (1943)

Bridge in Y-City (1943) Tree-Lined Street (1943)

Tree-Lined Street (1943) Woman with sculpture (1948)

Woman with sculpture (1948)

Further reading

- Iwate Museum of Art, et. al., eds. Matsumoto Shunsuke ten: Seitan 100-nen, exh. cat., Sendai: NHK puranetto tōhoku, 2012.[2]

- Sandler, Mark H. "The Living Artist: Matsumoto Shunsuke's Reply to the State." Art Journal 55, no. 3 (Autumn 1996): 74–82.[3]

- Usami, Shō. Ikebukuro Monparunasu Taishō demokurashi no gakatachi, Tokyo: Shūeisha, 1995.[5]

- Usami, Shō. Kyūdō no gaka Matsumoto Shunsuke hitamuki no sanjūroku-nen, Tokyo: Chūōkōron shinsha, 1992.[4]

Notes

- Matsumoto Shunsuke - website of the Iwate Museum of Art (retrieved 2013-05-01)

- Iwate Museum of Art, ed. (2012). Matsumoto Shunsuke ten: Seitan 100-nen. Sendai: NHK puranetto tōhoku.

- Mark H. Sandler : The Living Artist: Matsumoto Shunsuke's Reply to the State. Art Journal, Vol. 55, No. 3, Japan 1868–1945: Art, Architecture, and National Identity (Autumn 1996), pp. 74–82

- Usami, Shō (1992). Kyūdō no gaka Matsumoto Shunsuke hitamuki no sanjūroku-nen. Tokyo: Chūōkōron shinsha.

- Usami, Shō (1995). Ikebukuro Monparunasu Taishō demokurashi no gakatachi. Tokyo: Shūeisha.