Sicilian method

The Sicilian method was one of the first ways to extract sulfur from underground deposits. It was the only industrial method of recovering sulfur from elemental deposits until replaced by the Frasch process.[1] Most of the world's sulfur was obtained this way until the late 19th century.[2]

| |

| Process type | Extraction |

|---|---|

| Industrial sector(s) | Mining |

| Main technologies or sub-processes | Melting |

| Product(s) | Sulfur |

| Year of invention | Ancient |

In its most basic form the ores were piled in a mound and ignited. The semi-pure sulfur flowed down and the solidified mass was collected at a lower level. It gets its name from the center of sulfur production until the 19th century when it was replaced by the Frasch process.[3][4]

History

Sulfur, also known as brimstone (the stone that burns), has a variety of purposes such as bleaching agent, incense for religious rites, insecticides, and glue. The Romans used it to make fireworks and weapons. Sicilian industrial sulfur comes from the sedimentary Miocene rocks found about 200 meters underground.[5][6]

By the middle of the 19th century, Sicily produced 3/4 of the world's production. The excavation in Sicily was very easy and close to the surface. Local wages were low and underpaid children (carusu - 'mine boys') were used. Sicily also had easy transport by sea. The economy in Sicily was mostly agricultural, and the presence of sulfur mines helped support it. Nevertheless, extracting the sulfur created serious ecological hardship on the country. [7]

By 1912 the United States overtook Sicily for the worldwide production of sulfur. Large consistent bases of sulfur in Texas and Louisiana, as well as low-cost fuel and large quantities of water, made the newly invented Frasch process economical.[5]

After the Second World War, most of the mines in Sicily closed down.[8]

Process

Sulfur ore was carried up manually from shallow mines and placed in fire pits. The stones are heated to separate the sulfur from its other elements. However, the method is relatively inefficient as a significant part is burned instead of melting. There is also a large amount of pollution coming from sulfur dioxide.[9]

Sulfur, with a melting point of 115 °C (239 °F), is heated until it melts and flows downward with gravity. As it moves away from the heat source, it resolidifies and is collected. The sulfur obtained is not very pure.[8]

The Sicilian method went through four different phases of improvement. The first two were the main methods used in Sicily.

Calcarelle

Calcarelle was the most basic approach. A stack of ore was made of about 10 square feet (0.93 m2) in a ditch, and the floors were beaten hard and sloped downward, allowing the molten sulfur to flow to the bottom. The most significant pieces were stacked at the bottom with smaller pieces on top as the stack grew higher. This stack was then set on fire and by the third-day molten ore started to flow from an opening called a Morto (Death). Ore in the center melted more than the outside, which oxidized.[8] The yield could be as low as 6%.[10]

It was a very polluting approach and was not very efficient. Much of the product was destroyed and probably only yielded 1/3 of the total sulfur entering the furnace. The process could take days, depending on the weather. The side facing the wind tended to burn rather than melt, and efficiencies in the winter were lower.[10][11]

This archaic technology had the disadvantage of producing large quantities of sulfur dioxide and other compounds highly polluting and harmful for the health of workers, agriculture, and all the surrounding environment. It was required to install these rudimentary facilities at a distance of at least 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) from inhabited areas.[12] In 1870 there were about 4,367 Calcarelle in Sicily.[10]

Calcaroni

Calcaroni was a more prosperous and efficient method and replaced the Calcarelle method after around 1850.

Workers built a circular stone wall on an inclined slope. In front was the Morto (Death) or outlet, having a height of four to six feet and a width of two feet; over it is erected a wooden shelter for the workman in charge. Calcaroni may contain about 6 long tons (6.1 t). These could last ten years. The largest pieces of ore were selected for the first layer, leaving spaces between them, and the size of the lumps gradually diminished as the height increased. Narrow channels, about 2 feet (0.61 m) apart, are left for air to carry the heat down. The whole is covered with a layer of refuse from previous operations.[10] The internal floor inclined about ten degrees ending at the bottom.[8] The sulfur melts slowly downwards and, collected from the inclined floor, runs towards the exit. When the Morto was opened, the sulfur cooled into ingots called balate.[8] The process treated about 2000 cubic meters of ore at a time, and the process lasted for about 20-30 days. [8]

Although the number of pollutants and losses was considerably lower, Calcaroni produced a considerable mineral waste. Its yield was only around 50% due to the burning of the sulfur necessary for the heating process, which also caused environmental pollution.[8]

Doppioni

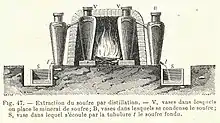

Doppioni (or Doppione) means double in Italian. Two terracotta vessels connected with a pipe, and workers heated one of the vessels, and workers put sulfur stones inside. The sulfur evaporated and passed through the pipe to cool down and poured into molds. This was more a process of distillation than melting. This process was used in other areas of Italy, such as Romagna, because of the need for fuels to heat the process other than sulfur, which Sicily lacked.[10]

Gill kiln

The Gill kiln was a continuous furnace developed in 1880 and named after its inventor, the engineer Roberto Gill. It employed a series of chambers to preheat and set fire to the next chamber. Each chamber had a floor with several openings for moving the molten sulfur. Each of the openings would move a shot of sulfur at different times and allow small amounts of sulfur to be processed. It was a costly system to put in place, but it also reduced many gas and pollution that entered into the air. It had yields of over 60%.[8]

Replacement

The Sicilian method was replaced slowly after 1894 by the Frasch process, or American approach. Workers processed the sulfur in the ground by superheating steam through a pipe to melt the sulfur in the ground extracting as it came up. This process led to a much purer form of sulfur, using fewer workers and less waste. This process needed a lot of fresh water and fuel, so it was never employed in water-poor Italy.[13][10]

See also

References

- Alden P. Armagnac (December 1942). "Strange mines tap sulphur". Popular Science. Popular Science Publishing Co. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- Stuart Bruchey (1960). "Brimstone, The Stone That Burns: The Story of the Frasch Sulphur Industry by Williams Haynes". Journal of Economic History. 20 (2): 326–327. JSTOR 2114864. It was a simple but not environmentally sound process.Walter Botsch (2001). "Chemiker, Techniker, Unternehmer: Zum 150. Geburtstag von Hermann Frasch". Chemie in unserer Zeit. 35 (5): 324–331. doi:10.1002/1521-3781(200110)35:5<324::AID-CIUZ324>3.0.CO;2-9.

- "Learn More About Sulphur - Introduction". The Sulphur Institute. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- Gray, C.W. (1920). Fundamentals of Chemistry. p. 76.

- Ingraham, John L. (7 May 2012). March of the Microbes. ISBN 9780674054035.

- Hunt, Walter Frederick (1915). "The origin of the sulphur deposits of Sicily". Economic Geology. 10 (6): 543–579. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.10.6.543.

- Mormino, Vincenzo. "Sulfur in Sicily". Archived from the original on 9 June 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- Kutney, Gerald (30 September 2013). Sulfur. History, Technology, Applications & Industry (2nd ed.). ISBN 978-1-895198-67-6.

- Notizie sullo zolfo di Sicilia e i suoi trattamenti Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- LOCK., WARNFORD (February 1885). "SULPHUR AND ITS EXTRACTION". Popular Science Monthly. 26: 482–495.

- Meyer, Beat (11 September 2013). Sulfur, Energy, and Environment. pp. 173–175. ISBN 9781483163468.

- La calcarella Archived 21 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Sulfur, Production History". Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2019.