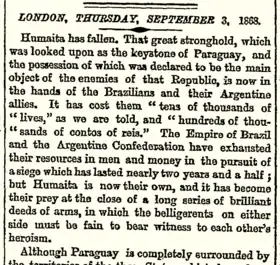

Siege of Humaitá

The siege of Humaitá was a military operation in which the Triple Alliance (Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay) flanked, besieged and captured the Fortress of Humaitá, a Paraguayan stronghold that was referred to as the Gibraltar of South America. It fell on 26 July 1868. It can be considered the key event of the Paraguayan War since the fortress had frustrated the allied advance into Paraguay for more than two years. However it did not surrender as the defenders escaped, most of them to fight another day.

The allies were severely criticised for the time it took them to take the installation, whose strength was belittled. But they were essentially a pre-professional army fighting a long way from home against an unaccustomed defence tactic: artillery in prepared, entrenched positions firing a hail of anti-personnel shot. Further, they were battling in unprecedented terrain — most of it impassible, all of it unmapped — in the wetlands of southern Paraguay. It gave the Paraguayans, who fought with exemplary courage despite being abysmally supplied, a huge advantage.

Moreover the allies, who at first had attempted to take the fortress by frontal attack from the Paraguay River, had instead suffered a catastrophic defeat; this had disorganised and demoralised their forces. Restoring their military effectiveness was a task that fell on the shoulders of the new commanding general the Marquess of Caxias. For political reasons he could not risk another disaster.

| Siege of Humaitá | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Paraguayan War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

At the beginning:[1]

At the end:[2] 1,324 |

At the beginning:[3]

| ||||||

| All numbers should be received with caution since 19th-century official military reports were often intended for public consumption. | |||||||

Context and importance

Brief recapitulation

The Paraguayan war was one of the major conflicts of the 19th century, and far and away the most lethal in the history of South America. Yet it is little known outside that continent.[4] It had three phases:

- Paraguay declares war on Brazil and Argentina — countries vastly more populous than itself[5] — invading three of their provinces.[lower-alpha 1] The two countries, plus Uruguay, sign the Treaty of the Triple Alliance, vowing never to lay down their arms until they have toppled Paraguay's leader Francisco Solano López.

- The Allies invade Paraguay, and at length capture its capital Asunción;

- Guerrilla warfare and the pursuit of López, who is finally killed by Brazilian cavalry after refusing to surrender.[6]

Its key event[lower-alpha 2] was the capture of the Fortress of Humaitá, which was the gateway to Paraguay, and had held up the allied advance for over two years.[7]

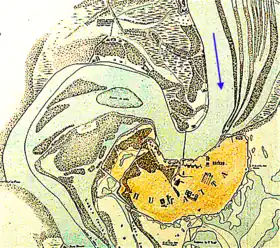

Location in heart of South America

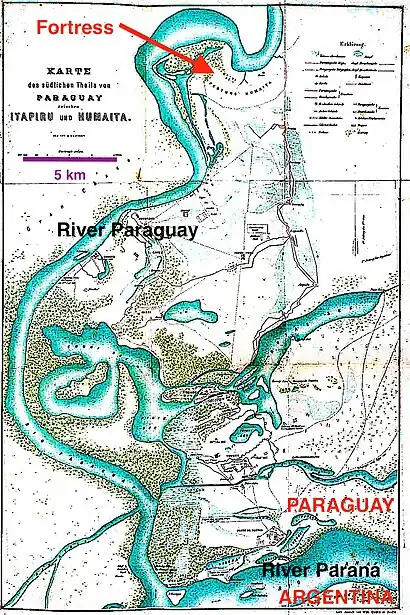

Location in heart of South America Context: wetlands of southern Paraguay

Context: wetlands of southern Paraguay

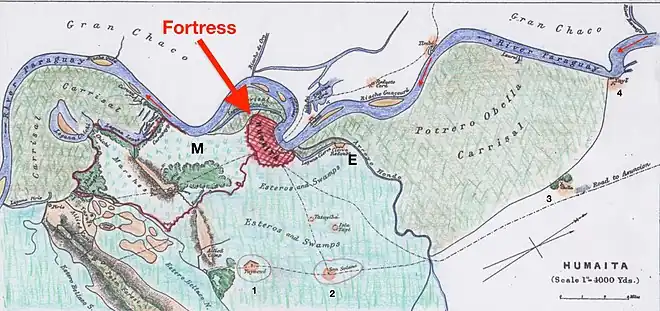

The maps show why the fortress was the key to Paraguay. The country is landlocked, but can be accessed from the sea; one must sail up two of South America's great rivers in succession:

- The River Paraná, which traverses many miles of Argentine territory. (A small portion of the Paraná is visible at the bottom of the Context map, marking the boundary between Argentina and Paraguay.)

- The River Paraguay, the country's principal highway,[8] and after which it is named.

As shown, Humaitá was a few miles up the river Paraguay. At first it was just a modest guardia or lookout point manned by a few soldiers.[9]

In the 1850s there had been two incidents in which Paraguay had been threatened by the naval flotillas of irate foreign powers, namely Brazil and the United States.[10] It became apparent that warships, though based in the Atlantic Ocean, could steam up into Paraguay quite rapidly.[11] Thus, the transition from sail to steam made the Paraguayan government realise that, far from being secure in the heart of South America, it was vulnerable.[12]

Accordingly, the Paraguayans had greatly strengthened the fortress of Humaitá. Its purpose was to bar the way in to Paraguay. Commanding a hairpin bend in the river, it had a formidable reputation.[lower-alpha 3]

Brazilian frustration

For the Brazilians the fortress was doubly vexing. It blocked the river route to their province of Mato Grosso, which lay hundreds of miles upstream, and had been occupied by Paraguay since the war began. It was by far the most convenient means of access to their territory,[13][14][15] a land about the size of Germany. Unless they got past Humaitá there seemed little prospect of recovering it.[16]

Attempt to take fortress by storm

Hoping for a quick result, the Allies tried to take the fortress by frontal assault from the river Paraguay.

On 22 September 1866 they landed troops on the edge of the only substantial piece of firm ground, a meadow marked M on the map Terrain. To attack in that place was a rational decision in itself, for they had hit upon a weak spot, and they might well have prevailed, greatly shortening the war. But their commands were divided, they dithered and delayed, and the Paraguayans built a defensive earthwork in the nick of time.[17]

Armed with artillery firing a hail of grapeshot and canister,[18] it destroyed the allied attack; many Argentine and Brazilian soldiers, advancing over open ground, were killed.

The Paraguayans, staying behind their defences, had few losses.[19]

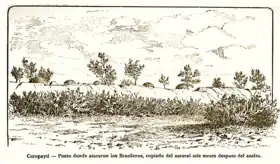

This was the battle of Curupayty, the allies' first major setback, and their worst defeat of the war.[20]

Summary: situation in October 1866

Thus, the allied armies, having landed in Paraguay, controlled only 9 square miles (2,330 hectares) of its territory:[21] inhospitable wetlands. Their advance was stymied by this seemingly invincible fortress; and, as will now appear. they were thoroughly demoralised.

Aftermath of the Battle of Curupayty

The allied advance into Paraguay came to a complete halt after the disaster of Curupayty.[22]

Command changes in the Allied army

The defeat caused dissension among the allied commanders and no one knew what to do next.[24]

After the battle, Joaquim Marques Lisboa, the Viscount of Tamandaré and commander of the Imperial Brazilian Navy, Polidoro Jordão, commander of the 1st Brazilian Army Corps, and Venancio Flores,[25] commander of the Uruguayan army, left their positions.[26] Tamandaré was replaced by Joaquim José Inácio[26] and Flores was replaced by Enrique Castro; according to historian Thomas Whigham, Uruguayan participation in the war was now reduced to a "token force only nominally Uruguayan in composition".[22]

The question of who should lead the Imperial forces remained however.[27] In Brazil, emperor Pedro II was determined to continue the war despite Curupayty; the new cabinet, headed by prime minister Zacarias de Góis e Vasconcelos, of the Progressive League, which rose to power seven weeks before the battle, was tasked with continuing the war.[28]

The emperor then nominated an experienced and prestigious general to lead the Imperial forces in Paraguay: Luís Alves de Lima e Silva, then Marquess of Caxias, by a decree on 10 October 1866.[29][27][30] The decree did not give Caxias command of the Brazilian navy; thus on paper it did not unify command of the Brazilian land and naval forces; despite this, the navy also fell under Caxias' command, and would no longer operate separately as it had done since the start of the war.[31] There was a concern on the part of the Brazilian government not to leave the navy under Argentine president Bartolomé Mitre's command.[30][32]

Caxias took his first steps by creating the 3rd Army Corps in Rio Grande do Sul already on 18 October 1866, while still in Rio de Janeiro.[33] He departed aboard the steamer Arinos on 29 October 1866, stopping at Montevideo on 2 November, Buenos Aires on 6 November, Rosario on 9 November and Corrientes on 14 November, finally reaching the allied camp in Tuyutí on 18 November. Upon his arrival, he issued his Order of the Day No.1, in which he stated to the troops that "if I didn't already know you, I would recommend you valour; but in the countless battles that have taken place to date, you have given ample proof of this military virtue"; the next day he assumed unified command of the 1st and 2nd Brazilian Army Corps.[26][34][35][36]

Epidemics and overall state of the army

At that point several diseases had spread in the battlefield, but a new cholera outbreak proved worst, killing or incapacitating thousands of soldiers;[37] the cholera epidemic became so serious that the Allied commanders tried to disguise it from both the Paraguayans and the civilian population in their respective countries, even prohibiting the use of the word "cholera" in official communications.[38] By March 1867 the epidemic had spread to Buenos Aires and Montevideo.[39] Less than a year later, on 2 January 1868, the illness was to kill Argentine vice-president Marcos Paz.[40]

The military camps did not follow basic hygiene practices and were filthy and disorganised.[41] The soldiers often drank contaminated water, which they got by excavacating the nearby sandbanks; the water was contaminated by dead bodies that were frequently buried near the water sources.[42] In order to cool a demijohn of water, the soldiers would dig a hole in the ground and bury it. Dionísio Cerqueira, a Brazilian soldier, later recalled, after having ordered a hole to be dug in his tent, that "as soon as the comrade had reached the bottom, we felt the characteristic smell of death. One more hoe hit and a rotten skull appeared. He plugged the hole and dug another one ahead".[43]

The sanitary conditions were not the only issue, for the organization and morale of the allied army were also abysmal.[44] Referring to the state of the 1st and 2nd Brazilian Army Corps, Caxias later stated that "they seemed to belong to two different nations", as each had their own administration, accounting, payment and promotion criteria.[45][26][46] This was also a problem in other units, especially the corps of Voluntários da Pátria (patriot volunteers).[46]

Another issue was the general lack of materiel: the cavalry lacked horses and the remaining ones were poorly fed;[47] the 2nd Army Corps, for example, was completely dismounted;[46] many soldiers had traded their uniforms and walked half-naked or barefoot; the Minié rifles used by the infantry needed a ramrod to function, many of which had been damaged; the artillery lacked heavy calibre guns, something that some observers pointed out as one of the causes for the allied defeat at Curupayty; there were also no ox carts or oxen to transport goods and troops.[46][48]

Federalist rebellions in Argentina

Ever since the signing of the Treaty of the Triple Alliance the commander-in-chief of all the allied forces had been Argentine president Bartolomé Mitre. After Curupayty, Mitre's prestige fell and growing 'federalist' rebellions in Argentina, headed by armed bands called montoneras, forced him to pay less attention to the war against Paraguay; this also meant that an increasing number of Argentine soldiers had to be diverted from the war to quell the rebellions in the Argentine interior, the most notable of which was led by Felipe Varela, a federalist and staunch opponent of Mitre, Brazil and the war against Paraguay.[49] For the Argentine federalists, Brazil was an enemy ever since its role in defeating Juan Manuel de Rosas during the Platine War fifteen years earlier.[50]

Suppression

In November 1866, 1,000 Argentine soldiers left the allied army and marched to Buenos Aires in order to join troops being raised there to put down the rebels; Mitre appointed general Wenceslao Paunero to command this army, but its effectiveness was limited and the rebellion continued; on 24 January 1867, 1,100 more Argentine soldiers were detached from the Allied army and sent back to Argentina in order to join Paunero's army; then, the Argentine president himself embarked on a steamer on 9 February 1867, heading back to Argentina with another 3,600 soldiers and leaving only four thousand Argentine troops in Paraguay under the command of general Gelly y Obes.[51]

Command of the allied army now de facto rested in Caxias' hands, who assumed it provisionally after Mitre's departure; such a reduced number of Argentine soldiers left in the front also meant the allied army strength now depended mostly on Brazil.[45][52] By April the rebellion was defeated; the rebels had received considerable aid from Chile, but could not resist the government force sent against them.[53] Mitre returned to Paraguay in July 1867, technically reassuming command of the Allied army, though Caxias continued to exercise extensive authority.[54]

The great reforms

Army reforms

The precarious state of the troops made a deep impression on Caxias, who concluded that serious measures were needed to make the army operable and continue the campaign.[55] The marquess later stated, after his return to Brazil, that "it was therefore necessary to call in everything, carrying out a new reorganisation and, for all of that, time was indispensable".[56] Caxias then set out to reorganise the army, step by step, gradually improving its morale, discipline and hygiene.[55] He took several months to reorganise and stabilise the front before deciding to resume allied actions; this made him a subject of mockery and criticism in the Brazilian press, which did not understand the issues surrounding the theatre of war.[24][26]

Sanitation reforms

Caxias' first measures upon assuming command applied to hospitals, ambulances, uniforms, food and transportation. He started to reorganise the Brazilian Army's depots in Argentina and Uruguay and the health service since his departure from Brazil.[26] The Brazilians had eleven hospitals in the region, four of which were in Paraguayan territory and all of which were overwhelmed by a large number of patients.[45][57] The allied army was in complete disarray. According to Francisco Doratioto, a third of the initial Brazilian force that had crossed the Paraná River into Paraguay was either sick or wounded by the time of Caxias' arrival, despite having received reinforcements.[45]

A medical commission led by Francisco Pinheiro Guimarães, a physician and colonel of Voluntários da Pátria who had already dealt with epidemics in Brazil, was nominated by Caxias to inspect the hospitals.[45] Guimarães isolated the cholera patients and instituted strict sanitation standards.[58] Caxias himself was meticulous in his habits, only drinking mineral water brought to him from Rio de Janeiro and ordering his quarters to be cleaned daily.[59] One of the goals of the commission was to inspect the hospitals to search for soldiers that were no longer sick and were overstaying with the doctors' connivance; fifteen days after the commission's creation, some twenty to twenty-five hundred soldiers were sent back to Tuyutí for active duty.[45][58]

In order to deal with the precarious state of the camps, Caxias also convened all division and brigade commanders for a meeting in which it was decided to create a Field Police Inspectorate. This unit would be responsible for inspecting whether the officers were following the organisation and sanitation norms or not.[60][61] The police inspectors' duties required them to be zealous for the camps' safety and order; for example, they included "not allowing games, gatherings, or disorder, and to patrol areas, especially the sutlers' districts'; and "list all existing female camp followers and make them rush to the hospitals as soon as the battle begins".[62] According to Aureliano Moura, this unit was the precurssor of what would later be the Brazilian Army's Police.[63] The marquess himself adopted the custom of making frequent morning visits to the brigades; in these visits he inspected the camps and the soldiers, paying close attention to their armament, uniforms and training.[64] Officers were often punished for sloppiness with the smallest details; some were even arrested.[65]

Army reorganisation

Parallel to the sanitation improvements, the marquess also reorganised the army. Caxias began by making changes to the army's administrative structure on 22 November by Order of the Day No. 2, merging several administrative divisions and creating others. He extinguished the post of chief of staff in the 1st and 2nd army corps while keeping it in his headquarters, along with two assistants, three engineers, four aides-de-camp, some officers and amanuenses. The next day, by Order No. 3, he started to reorganise the troops.[55] The units of Voluntários da Pátria were a great problem, for they were not standardised, with a varying number of companies and soldiers in each unit; on 20 December, they were restructured, with each one being assigned six companies.[66]

In addition, Caxias was also concerned with the tactics and procedures adopted by the troops in battle; he banned the use of any occupation badges in combat and reconnaissance missions, ordering the officers' kepi to be covered with a white tissue, similar to what the soldiers used; this demonstrated his willingness to set aside the old aristocratic pageantry if it interfered with the war.[34][61] During his routine visits, the marquess noticed that some officers were not following the battle formations provided for in the military regulations in effect at the time, especially the formation of squares against cavalry;[67] Order of the Day No. 5 had determined that whenever the infantry formed squares, it should do so in four rows.[61] Up until that point, new recruits were immediately handed guns and sent to battle, which could endanger the entire Allied army; to tackle this issue, from 7 December onwards all new recruits were given a fifteen day training on battle maneuvers and marching before being handed guns.[64]

The materiel deficiency was also remedied. The marquess convinced the imperial court in Rio de Janeiro to buy five thousand modern breech-loading Roberts and two thousand Spencer repeating rifles from the United States.[24] In order to teach the soldiers how to use the new breech-loading guns, Caxias ordered the 1st Army Corps to select 25 men who would be taught how to use them and then spread the knowledge to the rest of the troops.[66] An intense movement of provisions took place, with horses and mules being bought to be used in combat and in the transport of goods; the animals began to be fed alfalfa and corn, proper food that prevented them from falling ill.[68]

Caxias took fourteen months to implement these measures.[68] The results of his efforts were notable. The traveller Sir Richard Burton visited a Brazilian camp near Humaitá in August 1868 and was impressed by its hygienic cleanliness and how well the soldiers were sheltered, clothed and fed.[69] "Before he took charge, the Brazilian army was in the worst possible condition; now it can compare favourably as regards the appliances of civilization with the most civilized".[70]

Strategic decision: take Humaitá by siege

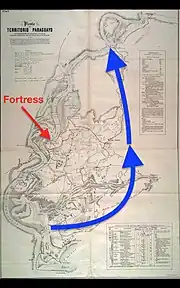

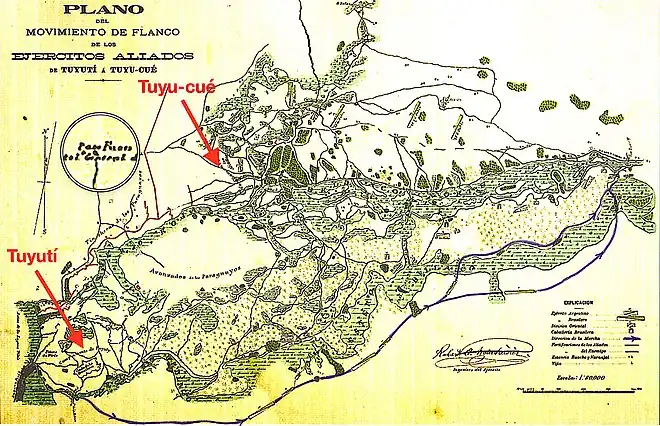

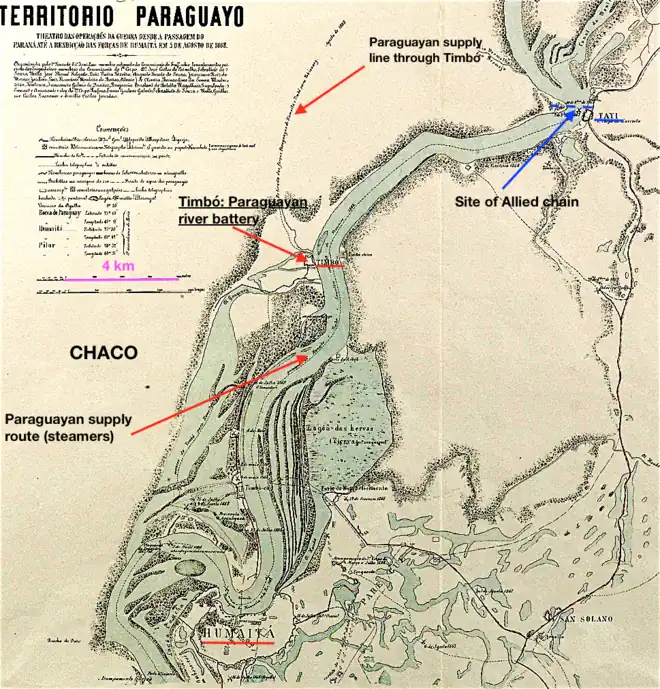

The plan that was to lead to the capture of Humaitá was as follows. Instead of attacking it frontally, it was to be broadly encircled from the rear and taken by siege. This required two operations, military and naval.

Allied troops, starting from their existing point of concentration — their base camp near the mouth of the river Paraguay — were to effect a flanking march well to the landward side of the fortress, giving its outer defences a wide berth, then marching to rejoin the river wherever it was convenient to do so. Thus the fortress would be cut off by land.[71]

But, though isolated by land, of course the Paraguayans would have continued to resupply the fortress by river, so it was necessary to cut it off by water too. Therefore the plan called for armoured Brazilian gunboats to force their way past Humaitá's batteries and deny the river to Paraguayan vessels. As explained in the article Passage of Humaitá, this was much easier said that done.

The plan had been proposed by Mitre and readily agreed by Caxias. (Long after the war, though, partisan Brazilian and Argentine journalists sought to belittle Mitre or Caxias and give sole credit to the other man.)[72]

When this plan was conceived the allies did not know where the river could be rejoined, since the local topography (carrizal, see below) makes this impossible in most places. Indeed López and his entourage came to believe the crucial information (that the river could be rejoined at a place called Tayí), and even the plan itself, was given to Caxias by a small group of Paraguayan defectors, including López's two brothers, Benigno and Venancio, the U.S. envoy to Paraguay being another one of the alleged conspirators.[73]

Implementation of the plan was nearly obstructed by the Brazilian navy, which refused to take orders from Mitre. Even after Caxias assumed supreme command they were very reluctant to proceed until forced into a corner, behaving heroically, though, when it came to the point.[lower-alpha 5]

The map shows the simple concept. In practice there were formidable difficulties to overcome.

Difficulties facing the Allies

Some foreign observers bitterly criticised the allies for the slowness with which they captured the fortress. It was even implied that corrupt motives might have to do with it.[74][75] In recent times some conspiracy theorists have reasoned that it was done deliberately as part of a Final Solution to exterminate the Paraguayan race.[76] Even Caxias himself, before he was given sole responsibility, grumbled that Mitre was in no hurry to get on with the war because Argentina was getting rich from it.[77]

The serious practical difficulties faced by the allies — who were operating without the benefit of hindsight — should therefore be described.

By water

Brazilian troops, artillery, ammunition and stores had to be brought to the vicinity of Humaitá from Rio de Janeiro by steamship: a 1,500 nautical mile (2,778 km) journey down the Atlantic ocean and up again through the rivers Plate, Paraná and Paraguay that took about a fortnight.[lower-alpha 6] Thus ocean-going ships had to steam up the Paraná river, where they risked running aground on its frequent sandbars.[78] The alternative, the overland route from Brazil to Paraguay was so bad that it was attempted only once, with disastrous results.[79]

Cavalry horses and draught animals died from eating "a poisonous herb called 'mio-mio',[lower-alpha 7] which abounds in the South of Paraguay, and which only animals reared in the district have the instinct to avoid".[80] Hence fodder had to be imported from downriver Buenos Aires or Rosario, its price rising to £8 gold[lower-alpha 8] per ton. According to Richard Burton, who visited the scene, "It was terribly wasted by exposure to wind and weather, and in places I have seen it used to bridge swamps. This unexpected obstacle added prodigiously to the difficulties and expenses of the invader".[81]

Terrestrial

The sea and river journey, though long, could be said to be the easy part. Cargoes were landed at Paso de Patria or Itapirú in southern Paraguay and had to be taken to their final destinations by mule cart. Convoys left once every two days and threaded their way through the marshlands.

By the time the allies had encircled the fortress, rejoining the river at Tayi, the route was many miles long. Those who went on it were liable to be ambushed and harassed by Paraguayan forces.[82]

When eventually the Brazilian armoured gunboats did dash past Humaitá and remake contact with the encircling land force they had to be resupplied via this tenuous route.

According to George Thompson

The Allies had to transport overland to Tayi all supplies and ammunition for their ironclads. They had to pay £2 10s for the transport of a 150-pounder shot, and £33 [say, $5,000 today] for the carriage of a ton of coal.[83]

Hence this vital line of communication — it was 70 km long[84] — might conceivably have been cut at any time if the Paraguayans had been bold and fortunate.

Hydrology and geology

To appreciate the wetlands terrain of southern Paraguay — where the allies were bogged down in an area of only a few square miles — it helps to understand some peculiarities of this portion of the river, called the Lower Paraguay.

The Lower Paraguay has a channel that is about 2,000 feet (600 metres) wide on average; it has a meandering pattern with an irregular and complex water regime. Its hydraulic gradient (mean slope) is very small (2 cm/km). When the water is high it cannot discharge into the Paraná fast enough: it backs up and causes extensive flooding. Not far above Humaitá it receives an enormous streamload of sediment, a mud brought from the slopes of the Andes by a tributary, the Bermejo River.

Thus, the Lower Paraguay is characterised by sediment erosion in the main channel and deposition in its floodplain channels. Although its left (eastern) bank is elevated, both banks are overflowed during the winter floods, as shown in the photographs from space, forming "meander scroll remnants, shallow lakes, ponds, marshes and long and narrow scroll-swamps"; the floodplain is poorly drained.[85] The local topography is continually changing, differing in summer and winter, and even from year to year.

Terrain

Once the Paraguayans had denied access to the meadow M at Curupayty, there were few pieces of firm ground upon which the allied troops could manoeuvre. Most of the surrounding terrain was almost impassible, and consisted of the following features; they were described by George Thompson, chief engineer of the Paraguayan army.

Carrizal. Extending from the river bank and up to three miles inland, it was land intersected by deep lagoons and deep mud, "and between the lagoons either an impassable jungle or long intertwined grass three yards high, equally impenetrable. When the river is high, the whole 'carrizal', with very few small exceptions, is under water, and when the river is low, and the mud has had time to dry, paths may be made between the lagoons".[86]

Esteros. Basically lagoons choked with stiff, gigantic aquatic plants, they surrounded the Paraguayan positions and formed their principal defence. "The water of these 'esteros'... is full of a rush[lower-alpha 9] which grows from 5 to 9 feet above the level of the water. The water in all standing ponds, is full of this rush..." These plants, called pirí, were triangular in section and grew perfectly straight.

These rushes grow about two inches apart only, and are consequently almost impassable in themselves. The bottom they grow on is always a very deep mud, and the water over this mud is from 3 to 6 feet deep. The 'esteros' are consequently impassable excepting at the passes, which are places where the rushes have been torn out by the roots, and sand gradually substituted for the mud at the bottom. In these passes, as in the rest of the 'esteros', the depth of water to be waded through is from 3 to 6 feet. In some places, one or even two or three persons, on very strong horses, can pass through the rushes ; but, after one horse has passed, the mud is very much worse on account of the holes made by the first horse's feet.[87]

The Chaco. On the opposite shore of the river began the Gran Chaco, a region so inhospitable it was never conquered by the Spanish Empire. Claimed by both Argentina and Paraguay, it was still uninhabited, except by the feared Toba people. The coastal region was almost impassible. Eventually, pressure of war obliged both sides to make quite extensive forays there; see below.

Lack of appropriate experience

The allies had no experience of fighting or manoeuvring in terrain such as just described. Open, mobile warfare was the preferred style in South America where wars were quick and decided through pitched battles.[88]

Both sides learned the folly of attack over open ground, the Paraguayans at the Battle of Tuyutí and the allies at Curupayty. Around Humaitá "there was a conglomeration of lagoons, marshes and patches of jungle connected by narrow strips of terra firma which the attacking side had to squeeze through on a narrow front": this conferred a huge advantage on the defence.[89]

Unaccustomed defence tactic

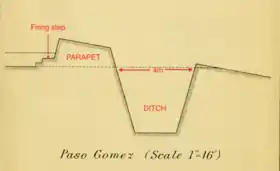

A simple defence tactic was employed which was unusual in South America.

"The Paraguayans had not many infantry, and they relied most on their artillery in case of an attack", said their chief engineer. The artillery would fire grapeshot or canister — a hail of small shot which was a crude predecessor of machine-gun fire. While this was commonplace in itself, what was unusual was its deployment from earthworks.

The earthworks were made by digging a ditch about 12 feet wide and 6 feet deep (~ 4 x 2 m). The soil was used to construct a thick parapet. The defenders sheltered behind the parapet and so the attackers had to cross the ditch before they could climb it. As practised in Paraguay the slope of the ditch and the parapet were made continuous; this made it particularly tall and hard to climb. Soil with such a steep slope will collapse e.g. as soon as it rains[90] and so it was revetted with thick sods cut from the grass-covered earth. To some extent this lining was fractured by enemy artillery rounds but turf in Paraguay was much harder than in Europe.

Infantrymen on the firing step fired at the enemy over the parapet. Small salient angles were made to allow the artillery guns to project forward, or they were raised on platforms to fire over the infantrymen's heads. Such an arrangement (en barbette) demanded courage from the artillerymen because they were unprotected, but on the other hand gave them the widest possible field for action. By resting the ends of the earthworks on the esteros or other impassible terrain they could not be flanked.[91]

As to the strength of such defences, cadets at West Point were taught general Horatio Gouverneur Wright's maxim: "A well intrenched line, defended by two ranks[92] of infantry cannot be carried by a direct attack".[93] (When the use of defensive earthworks had been resorted to in the Great Siege of Montevideo — the nearest precedent — it had baffled the attackers for 8 years.) As will be described, four times a direct attack was tried in this campaign. The attacker casualties were enormous and it did not work except against heavily outnumbered defenders.

Pre-professional officer corps

When an army faces an unprecedented situation much depends on the professionalism of its officer corps. "Until 1865, the Brazilian army was essentially pre-professional", wrote American scholar William S. Dudley: its officer corps did not awaken to the need for modernisation and renewal until after the war.[94][95] For Leslie Bethell, a modern, professional army was created by Caxias only in the course of the campaign itself.[96] The Argentine and Uruguayan officer corps certainly were not better prepared since, unlike the Brazilians, they did not even have an adequate supply of military engineers.[97]

No maps

While the Paraguayans were familiar with the ground, maps of the territory were, for the allies, non-existent. At first completely ignorant of the terrain, they did not even realise that Humaitá was protected by miles of earthworks.[98]

The allied base camp was frequently harassed by Paraguayan snatch squads that used to kidnap the sentries (see below). The allies did not realise why: they had placed their camp right next to a corner of the Humaitá trench works: the el Sauce corner. It was hidden from them by the thick vegetation.[lower-alpha 10]

There being no maps, they had to be created. The Brazilian cavalry frequently went out to reconnoitre but this branch was adapted for relatively open ground. At ground level men could not see far because of the vegetation. Two other methods were resorted to.

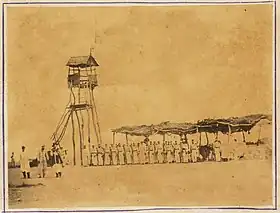

(a) Mangrullos

These were improvised watch towers. Richard Burton saw and described them;

The rough contrivance, varying from forty to sixty feet in height, is composed of four or more thin tree-trunks, planted perpendicularly, and supplied with platforms or stages of cross-pieces, mostly palms, the whole being bound together with the inevitable raw hide. The look-outs are ascended by notched palm-trunks, or ladders, which, after a little neglect, become dangerous... In so flat a country the mangrullo acts well.[99]

In August 1866 the Polish engineer Robert Adolf Chodasiewicz of the Argentine army, who had acquired his skills in the Crimean War, had made a preliminary map of the area south of Humaitá; he did so by triangulating from three mangrullos.[100]

Chodasiewicz added further refinements after the battle of Curupayty. With the consent of Caxias a copy of his map was given to Charles Washburn, the American envoy to Paraguay, who was passing through the allied lines, knowing Washburn would show it to Francisco Solano López. López was impressed by its accuracy and became convinced there was a traitor in his ranks who had sold the information to the allies. Suspicion fastened on his brother Benigno; in 1868 he was shot for treason.[20]

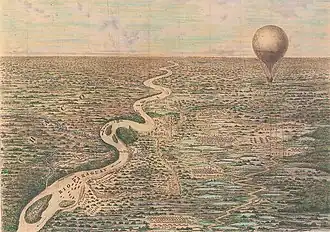

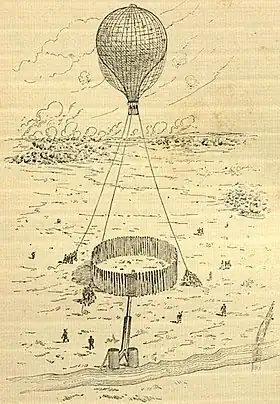

(b) Observation balloons

On the initiative of the Emperor Pedro II himself and the War Minister João Lustosa da Cunha Paranaguá, Marquess of Paranaguá,[101] the Brazilian government contracted the Allen brothers, veteran balloonists of the American Civil War, to establish a balloon surveillance unit. They were recommended by Professor T. S. C. Lowe, formerly chief aeronaut of the Union Army Balloon Corps.[102] The brothers imported two balloons. These had cotton envelopes, which were varnished to make them gas-tight, and were filled with hydrogen, which was made by mixing iron filings with sulphuric acid. It was the first time aviation was used in South American warfare. The balloons did not fly freely: they were tethered by manilla ropes and could be maneouvred by teams of 30 men trained for the purpose.

To the exasperation of Caxias the iron filings had not been despatched from Rio de Janeiro, so lump iron had to be substituted; hence the apparatus would not generate very much hydrogen. In consequence, ballooning was delayed, and the larger balloon, which could have carried more observers, was not used at all.[103] The smaller balloon had a diameter of 8.5 metres,[104] or 9 metres, according to another source.[105]

The first ascents were made in June and July 1867. In the second of those the balloon rose to 400–450 feet (120–130 m) and stayed up two hours. In the basket were Chodasiewicz and a Paraguayan scout. Recalled the Pole:

With the aid of a long distance eyepiece we could make out — for the first time — all those formidable lines of fortifications. We saw the whole Paraguayan Quadrilateral; its el Sauce corner, concealed in the jungle, bang in front of our army's extreme left ... also its SE corner redoubt united with Humaitá's [inner] trenches[105]

Barely a fortnight after this ascent, Caxias began his great flanking march.[106]

Although Caxias used the balloon again on his flanking march, he would not allow it to be used in advanced positions, and the Paraguayans took to making grass fires to obscure the area with smoke.[105][107][108] Altogether some 20 ascents were made.[109]

Paraguayan harassment

As a general López has been criticised for frequently sending units on attacking manoeuvres which, although audacious, had no clearly defined military objective, thus frittering away his scarce manpower.[110][111] Even so, by continually taking the initiative the Paraguayans helped to depress the allied soldiers, bored by their own side's caution.

"When López wanted news from the allied camp, he used to send some of his spies to kidnap a sentry, in which they were very successful", said Thompson. Sometimes a sentry would be snatched away[112] or be stabbed to death silently in the dark.[113] As noted, allied convoys were frequently attacked, and cavalry patrols led into ambushes.[82][114]

Paraguayan bravery and discipline

The Paraguayan soldier's indifference to danger was legendary. In his memoirs George Thompson, who rose to be a lieutenant colonel in the Paraguayan army, wrote "If a Paraguayan, in the midst of his comrades, was blown to pieces by a shell, they would yell with delight, thinking it a capital joke, in which they would have been joined by the victim himself had he been capable".[115]

Paraguayan soldiers were strictly disciplined. Even a corporal could give any soldier three blows with his cane on his own authority; a sergeant, twelve; an officer, almost any number.[116] Thompson recalled:

The Paraguayans were the most respectful and obedient men imaginable... A Paraguayan never complained of an injustice, and was perfectly contented with whatever his superior determined. If he was flogged, he consoled himself by saying, 'If my father did not flog me, who would?' Everyone called his superior officer 'his father', and his subordinate 'his son'. López was called 'taitá guasú',[lower-alpha 11] or big father.

As in the French army, all officers were promoted from the ranks. "Young men of good family, who were enlisted, had to take off their shoes and go barefooted, as none of the Paraguayan soldiers were allowed to wear shoes".[117]

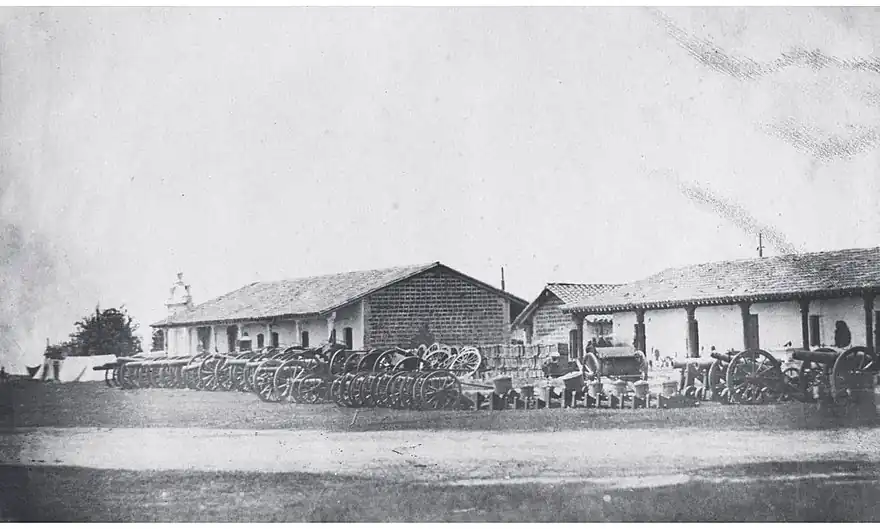

Strength of the fortress

Such was Humaitá's reputation for impregnability that it was referred to in the American or European press as the Gibraltar, Sebastopol or Vicksburg of South America.[lower-alpha 12] This led observers to expect a formidable structure of brick or masonry and they were disappointed when they saw the reality. However, the fortress' real strength lay in its natural defences.[118]

Its strategic purpose was to stop enemy ships invading Paraguay. The site was a tight, 2,500 yard, horseshoe bend in the river surmounted by a low cliff; a sequence of batteries overlooked the bend and could concentrate converging fire upon the shipping. To prevent enemy vessels dashing past the batteries at full speed there was a chain boom that could be raised to detain them under the guns.[119]

Around this time ironclads (vessels protected by thick iron plates) were being adopted in warfare, and Brazil had a number of these. Immensely strong, none were sunk by Paraguayan gunfire (although one was lost to a "torpedo", see below). However their disadvantage was that they were so heavy that they might run aground when the river Paraguay fell (which happened seasonally, by as much as 14 feet)[89] leaving them trapped.

Further to deter enemy ships there were "torpedos" — really, improvised naval mines — that could be tethered or released in the stream. These were very unreliable, and usually failed to go off on target, but as Burton remarked "even disciplined men feel a natural horror of, and are easily demoralized by, hidden mysterious dangers so swiftly and completely destructive".[120] Indeed, the Paraguayans did manage to sink one Brazilian ironclad, Rio de Janeiro, using these mines.[121]

They made the Brazilian naval command very reluctant to proceed.[122] They had to be cajoled and persuaded by the Brazilian government.

The fortress proper was protected on the landward size by natural defences (see above, Terrain), and by 8 miles (13 km) of earthworks.[123] The whole installation was defended by 400 artillery pieces.[124] (The illustration shows one of the most famous, the Cristiano, which survives today.)[125] A system of telegraph lines could send troops swiftly to any threatened point.

At this time the whole installation was garrisoned by a force of 20,000 troops, of which at least 10,000 were first class fighting men; Paraguayan soldiers were famed for their valour and ferocity.

After Humaitá was taken, some detractors said its strength had been grossly exaggerated (see below). Even if this was so, they said it after the event. At the time its reputation for invincibility, both naval and military, made it a formidable psychological barrier.[126]

The home front

Whatever the defects of the allied governments, and there were many, in their countries elections were held and people voted.[127] They had vociferous opposition parties — unlike Paraguay — and these could win.[128] Parties in power knew it, and could not afford to ignore public opinion. As to that, there was much war-weariness,[129] and in Argentina, outright rebellion. The war was badly affecting the allies' financial credit.

The situation in Argentina was particularly critical. Although the Argentine military contribution was, by now, modest in comparison with Brazil's, the country remained important strategically and geographically. The alliance with Argentina gave Brazil something invaluable — a good base of operations against Paraguay.[130] Had Argentina made peace it is not obvious how its allies would have continued.

For these reasons, the military simply could not risk another disaster like Curupayty. In the words of an Argentine diplomat, "If Caxias attacks but doesn't win this time, the situation will go to hell".[131] Caxias felt obliged to proceed cautiously — "painfully slowly" (said his detractors); "slowly but surely" (said his admirers).[132]

Argentina: Not yet a national state, but a deeply divided country

The federalists who were rebelling in Argentina were motivated by much more than anti-Brazilian sentiment. The catalyst was conscription in the Paraguayan war, which bore harshly on the sparsely populated western provinces[133] where "Mitre's governors had to use iron shackles to smooth their recruitment efforts".[134]

But these federalists hated Mitre and his Buenos Aires liberales anyway — on principle. Varela's slogan was

Down with those who usurp the revenues and rights of the provinces for the benefit of Buenos Aires, a vain, despotic, and indolent people.

Argentina had not yet succeeded in building a national state; only recently had the secession of the State of Buenos Aires from the Argentine Confederation come to an end after nearly ten years of war. Constitutionally now, the struggle was between Liberal state-building under Buenos Aires domination and Federalist provincial autonomy. The antagonism, which had roots going back to the country's independence from Spain, was between town and country; "ethnic and class conflicts between the white Liberal urban elite and Federalist rural mestizo gauchos", said David Rock. Both sides engaged in political assassination and looting. Further, the Varela rebellion, which was in the Andean provinces, had the backing of the Chilean government. Before the Bourbon reforms the Cuyo provinces had been part of the Spanish empire in Chile, not Argentina, and the rebels declared it was their intention to restore them to Chilean rule.[135]

Indeed it has been argued that the Paraguayan war was only part of a broader conflict in Spanish America: "a struggle for mastery between the modernizing factions led by presidents Mitre and Sarmiento in Buenos Aires, who wanted to develop links with European capitalism and a world market, and the conservative opposition represented by Paraguay, the blancos of Uruguay, and the federalists of Argentina, who wished to cling to a traditional way of life".[136] For the latter, López was their champion; even before the war, the federalists of La Rioja province were jokingly dubbed the "Paraguayan Club".[137] In 1868 Varela, in conjunction with president Mariano Melgarejo of Bolivia, sent a representative to Paraguay to solicit funds for his Argentine revolution; Melgarejo promised 100,000 soldiers to support it.[138]

As it happened, these Argentine rebellions did not help Paraguay: they greatly prolonged the war and the ensuing loss of life: see below.

Difficulties facing the Paraguayans

A force of about 20,000 men — the bulk of the remaining Paraguayan army — defended Humaitá. They had to be fed. Cut off by swamp, it was a very difficult position to supply. Some supplies were brought in by steamships, or by a fleet of canoes, and landed by night to avoid the Brazilian navy, though the shipping was never enough.[139]

Scarcity of customary vegetable food

.jpg.webp)

The marshy soil was ill-adapted for growing the staples of the average Paraguayan's diet, manioc and maize; these were in short supply. The main foodstuff was poor quality beef. The unaccustomed fare[140] caused dysentery amongst the troops; the affliction was the biggest killer in the Paraguayan army.[141]

Precarious meat supply

Fresh beef would not keep, nor could it be salted because salt was almost unprocurable. Most beef was sent on the hoof. Cattle were driven towards Humaitá along a coastal road from the north. However, supplies were precarious, because parts of the route went through swampy terrain, and it flooded in winter.[142]

To the north of the fortress was a large carrizal called Potrero Obella which effectively acted as a holding pen for cattle. Seemingly inpenetrable, it had a single opening by which the incoming cattle were secretly introduced; furthermore, a single exit by which they were taken out, as required, to feed the garrison at Humaitá.[143] The discovery and capture of the entrance of Potrero Obella, see below, was therefore important.

Lack of dietary salt

Traditionally, Paraguay's salt was manufactured by women who extracted it from deposits at a place called Lambaré, but the war disrupted their activity and salt became almost unavailable,[144][145] according to one source not being enough even in hospitals.[146] Salt is lost by sweating and more so in diarrhoea (as in dysentery). Insufficient dietary salt causes weakness and, eventually, lethargy, apathy and final coma.[147]

Medicines

There was a serious shortage of medicines, notably calomel (used for internal parasites) and laudanum (an opiate, the only known treatment for dysentery).[148]

Cholera

In May 1867 cholera broke out in the Paraguayan encampment too. Two large cholera hospitals were established. Many officers and men died of it; a loss of manpower that López could ill afford. López himself thought he had it; according to Thompson he became enraged and accused his doctors of trying to poison him.[149]

Clothing

There was a serious shortfall in production of clothing for uniforms. Winters can be cold in southern Paraguay and attempts were made to manufacture leather overcoats, but the damp cold weather made them unmanageably stiff. "The Paraguayan soldier was barefoot, ragged, and usually malnourished". It was noted that captured allied soldiers were immediately stripped of their uniforms.[150]

Bad horses

In his memoir of the war George Thompson, chief engineer of the Paraguayan army, wrote

One of the greatest drawbacks with which the Paraguayans had to contend during the war was the wretched state of their horses. Aides-de-camp and commanders of corps were mounted on jades with nothing but skin and bone, and which could not possibly go beyond a poor walk; and they frequently stopped on the road, not being able to move another step...

The Paraguayan cavalry was very badly mounted; their miserable animals were continually dying off, and being replaced by wild horses, which the men had to tame. Notwithstanding this, the enemy's infantry could not stand a charge of the Paraguayan cavalry, nor could the Paraguayan infantry compete with the Allies' cavalry, which was well mounted.[151]

Condition of troops

In September 1867 G.F. Gould a British diplomat passing through the lines at Humaitá reported:

The Paraguayan forces amount altogether to about 20,000 men, of these 10,000 or 12,000, at most, are good troops, the rest are mere boys from 12 to 14 years of age, old men and cripples, besides 1,000 to 3,000 sick and wounded. The men are worn out with exposure, fatigue and privations. They are actually dropping down from inanition... Many of the soldiers are in a state bordering on nudity, having only a piece of tanned leather round their loins, a ragged shirt, and a poncho made of vegetable fibre... A great part of them are still armed with flint guns.[152][153][154]

Boy soldiers may seem an exaggeration, but it is confirmed by a López decree of March 1867.[155]

Despite this, continued Gould, Paraguayan soldiers fought bravely and well:

The Paraguayans are a fine, brave, hardy and obedient race of men... They neither give nor accept quarter [mercy], even when wounded. Paraguayan wounded have been seen, when lying in the field almost in the agony of death, to stab any enemy wounded in reach. Others ... refuse pertinaciously to surrender, and have to be run through where they lie.[152]

"The Paraguayan soldier ... destroyed himself by his own heroism", wrote Richard Burton.[156]

"Hunger continually stalked the Paraguayan soldiers" wrote Jerry W. Cooney. Already in 1866 the allies noticed that the corpses of Paraguayan soldiers were so emaciated that they could not be burned. They would not decompose. Thompson saw it with his own eyes ("These bodies were not decomposed, but completely mummified, the skin having dried on to the bones"),[157] and it is corroborated by Masterman, a British pharmacist doing duty in the hospitals of Asunción: he said the wounded from Humaitá who died there dried up without decomposition.[158] For Professor Cooney, it was the lack of food that doomed the defenders of Humaitá.[142]

The Allied flanking march

Starting point: allied base camp at Tuyutí

Several months after Curupayty, after being reinforced with an additional twenty thousand men of the newly created 3rd Army Corps, under the command of Manuel Luís Osório, and containing the cholera epidemic, Caxias finally resumed operations.[159] The Allied army now counted around forty-five thousand men: forty thousand Brazilians, less than five thousand Argentines and some six hundred Uruguayans.[3]

On 21 July 1867, the marquess issued his Order of the Day No. 2. The bulk of the men, 38,500 of them, Brazilians, Argentines, and what was left of the Uruguayans; infantry, cavalry and artillery; all were to march to Tuyu-Cué at dawn on the morrow; the rest of them, 13,000 men, were left as a garrison under the command of Manuel Marques de Sousa, then Viscount of Porto Alegre.[160] The next day, Caxias began the movement in order to flank and surround Humaitá.[68] The allies were on the move again.[106]

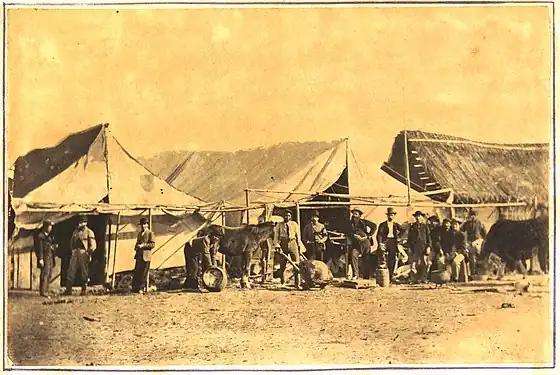

The starting place was at Tuyutí in the south, a low ridge not far from the river Paraná, where most of the allied troops were camped out, and had been since they crossed the river from Argentina more than two years before. By now the area was like a substantial town with many shops (see below, Second Battle of Tuyutí).

The march through the marshes

Tuyu-Cué was only about 5 miles from Tuyutí as the crow flies, but the Paraguayan trenches (marked as thin red lines in the map) barred their way. The allied forces had to go around, dealing with the Estero Bellaco, a notorious sedge marsh (bellaco translates as "tricky" or "cussed"). This marsh was partly an internal, flowing waterway connecting the rivers Paraná and Paraguay.[87] The roundabout route was 28 miles (45 km) long. It took them 10 days: it must have been the most difficult portion of the entire flanking march.

There survives a map drawn by the military engineer Chodasiewicz that highlights the challenge. In their way were both branches of the Estero Bellaco — north and south. The Argentine contingent crossed the south arm by a pass that had been discovered by the scouts; owing to some misunderstanding the Brazilians continued to march on beside the southern edge of the marsh and encountered soggy ground, which made for slow going. If López had had the presence of mind he would have attacked the Argentines, said a Paraguayan officer after the war,[161] for the Brazilians being on the other side of this sedge-choked waterway could not have come to their assistance.[162]

But at last they were north of the Bellaco. The ground was firmer. There were signs of human habitation and, as the map shows, there were usable trails. They made camp, some of them in the orange groves.

On the 30th a skirmish occurred with a Paraguayan force involving cavalry and artillery, The Paraguayans retired; according to Chodasiewicz they left 80 dead and three Congreve rocket stands.[163]

In the afternoon Mitre arrived in the camp, having put down the Argentine rebellions, and reassumed command.[163][164]

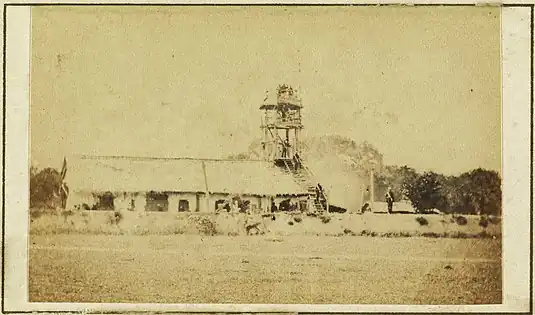

Tuyu-Cué: the allies' new headquarters on the edge of the marsh

Tuyu-Cué, significantly meaning "mud-that-used-to-be" in the indigenous language,[165] was a rare settlement on the edge of the marsh. A fairly typical Paraguayan capilla whose main building was a low, thatched church, it was now deserted on López's orders. The church would be commandeered as a field hospital.

Tuyu-Cué was to be the allies' headquarters throughout most of the siege. Bizarrely, López's headquarters at Paso Pucú was just two miles away: the closest he and Caxias ever got.

The siege begins to close

López builds an emergency road through the Chaco

Realising he was being flanked, and might have his communications cut off, López began to prepare an alternative supply road — and potential escape route — through the Chaco, on the other side of the river. The countryside there was very inhospitable,[166] but López had it explored. He decided to make a road cutting across the Chaco and rejoining the river Paraguay many miles north, at a place called Monte Lindo. Monte Lindo was in the inhabited part of Paraguay north of the Tebicuary River, a tributary of the river Paraguay.

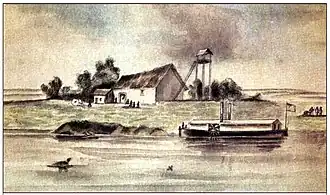

The nearest place opposite Humaitá where a landing could be made was called Timbó; it was the southern terminus of the road.

According to Thompson, who travelled it himself

This road through the Chaco was tolerably straight, and was fifty-four miles long. It did not follow the course of the River Paraguay, but went inland. The greater part of the road went through deep mud, and five deep streams had to be crossed, besides the River Bermejo. Almost the whole way the road lay between woods, which, long, narrow, and tortuous, are scattered over the whole of the Chaco. The land is perfectly flat, and is intersected by numerous 'esteros'. Posts were immediately established along the whole length of the road.[167]

A force under colonel Nuñez was sent to guard the pass over the Tebicuary. He was in charge of resupplying Humaitá by remitting the cattle, supplies, and correspondence through the new road in the Chaco. First, the cattle had to get to the Chaco. To do that they had to cross the river Paraguay, which at this point was 500 yards wide with a rapid current. Heroic methods were used to make them swim it, but many drowned until it was decided to tow them across in a pontoon.[168] After travelling south on this 54-mile road — which required them to get across the five deep streams plus the river Bermejo, of course — the animals were conveyed back across the river Paraguay in steamers to Humaitá.

It is hard to find that anyone had made any sort of road in the Chaco before, let alone one of this length. By building it López changed the dynamics of the siege.[169] Later, when it was tightened in earnest, he used it to escape with the bulk of his army, see below.

San Solano

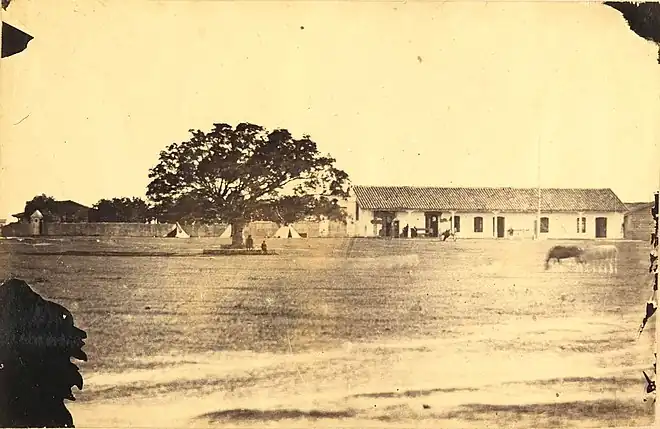

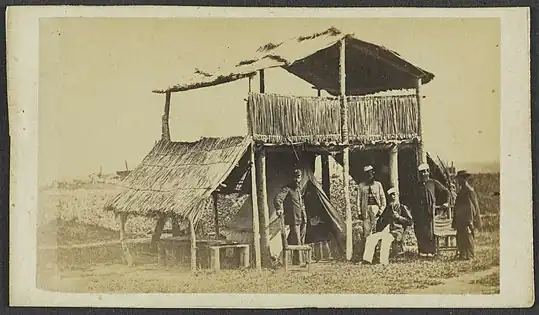

At the same time as the allies occupied Tuyu-Cué a detachment went further north to reconnoitre San Solano. This was a state farm opposite Humaitá, though about 6 miles away. There was a strip of dry ground[143] suitable for camping, and it was not far away from what Thompson called "the high road leading from Humaitá to Asunción[170] which, however, was a rough trail at best.[lower-alpha 14]

San Solano, dwelling of cavalry hero the Baron of Triunfo. Notice earthwork defence.

San Solano, dwelling of cavalry hero the Baron of Triunfo. Notice earthwork defence. Dry ground must have been a rare luxury — notice where the tent is pitched

Dry ground must have been a rare luxury — notice where the tent is pitched

Later, when the allies captured Tayí on the river, a force of 10,000 men was kept at Solano to reinforce them if need be.[171] As the surviving photograph shows, it was protected by earthworks. The main links in the allied chain encircling Humaitá were thus: Tuyutí, Tuyu-cué, San Solano and Tayí.

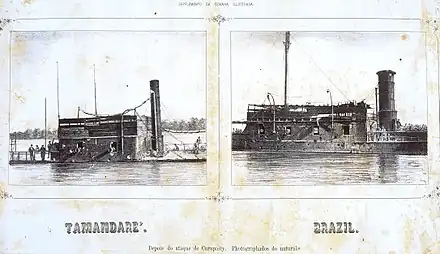

Passage of Curupayty

On 15 August 1867, in an event known as the Passage of Curupayty, ten Brazilian ironclads dashed past the guns of Curupayty, an outwork of the fortress of Humaitá near the scene of the fateful battle. They were able to do so even though the Paraguayans had brought most of their heavy guns from Humaitá, including El Cristiano. Despite the ferocity of the bombardment only 3 sailors were killed and 22 wounded.[lower-alpha 15] It made the Paraguayans realise their best guns could not stop these Brazilian armoured vessels.[172][173]

Peace proposals

Three days later a British diplomat, who had been sent to Paraguay to negotiate the release of some British citizens, framed some conditions of peace which (he said) the López government authorised him to put before the allies. The terms were quite favourable to Paraguay,[174] but López had to retire to Europe. The diplomat crossed the allied lines under a flag of truce, where the proposals were favourably received. However, on re-crossing the Paraguayan lines there was a setback: the Paraguayan government categorically denied the term about López retiring had ever been part of proposals. (The real reason, according to more than one source, was that López had changed his mind, having just learned of another revolution in Argentina — indeed, being urged not to make peace by an Argentine enemy of Mitre.)[175][176] In Professor Whigham's estimation,

These terms were the best he was offered during the war, and he spurned them... It was easier to conclude that the Marshal was willing “to sacrifice the last man, woman, and child of a brave, devoted, and suffering people, simply to keep himself for a little while longer in power".[177]

The ironclads were trapped between Curupayty and Humaitá for some months, but they were able to manoeuvre, and their gunfire sank the pontoons on which the great chain boom rested, sending it to the bottom of the river.[lower-alpha 16] The way past the fortress of Humaitá was now open.

Potrero Obella

Anticipating the siege, López decided to get in more food, which he did by introducing a large stock of cattle into Potrero Obella, the secret hiding place already mentioned. Brazilian cavalry discovered the entrance, which was several miles north of San Solano and was defended by a Paraguayan trench; and general Mena Barreto with 5,000 men was ordered to take it, which he did on 29 October[lower-alpha 17] with considerable loss on both sides, especially Brazilian; the heavily outnumbered defenders could not be expelled from their earthwork except by a barrage of artillery shells.[178][179][180]

Tayí: completing the circle...

On the next day Mena Barreto's reconnoitring cavalry reached Tayí. A disused guardia (lookout point), it was the first place on the river after Humaitá where the carrizal permitted a landing to be made. Thus, if the manoeuvre could be consolidated, the flanking march would be complete. Mena Barreto exchanged fire with two passing Paraguayan steamers and retired.

On 1 November, López, fearing the allies would place a battery at Tayí and interdict his shipping, sent a steamer with George Thompson to mark out a trench and a force of infantry and artillery to defend it. Mena Barreto was close by, and there was no time to complete the trench before he attacked next morning. The Paraguayans got below the low cliff but most were killed by the Brazilian force. Thompson thought that if he had been allowed to fortify the guardhouse instead of making the trench the Paraguayans could have held the position.

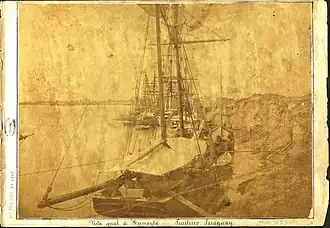

Three Paraguayan steamers began to bombard the Brazilians, who brought up artillery and fired with rifles, presumably Spencer repeaters, since they killed most of the crew. Two of the steamers, Olimpo and 25 de Mayo — the latter had been captured from Argentina at the start of the war — were sunk. The Brazilians immediately entrenched themselves and garrisoned the position with 6,000 men.[181]

The fortress of Humaitá was now cut off by land. López kept it a profound secret in Paraguay; it was not mentioned in the newspapers; at headquarters it was whispered on a need-to-know basis.[182]

... and blocking the river

Further, the allies stretched chains across the river Paraguay at Tayí and placed a battery. Paraguayan shipping could not run past, despite trying to improvise a rudimentary ironclad.[171] So Humaitá was cut off by water too, except that the Paraguayans could still resupply it through the emergency Chaco road and Timbó.

Two of their steamers had already passed downriver before the chains were stretched across. These vessels — the Tacuarí and the Ygurei, the best in the Paraguayan navy — were employed to ferry the supplies from the road's terminus at Timbó to Humaitá, about 10 miles. They were invisible to the Brazilian ironclads, who were still trapped between Curupayty and Humaitá.[183]

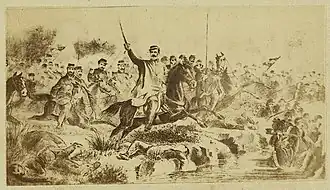

Second Battle of Tuyutí

With most of the Allied army dispersed between Caxias' base at Tuyu-Cué and Tayi, the Paraguayans noticed that Tuyutí became an easy target.[184] López decided that an attack on the allies' base camp at Tuyutí might force Mitre to redeploy from Tuyu-Cué, interfering with his encircling plan. He also wanted to capture some of the allied guns.[185][186] Tuyutí was garrisoned by the 2nd Brazilian Army Corps, under the command of Porto Alegre.[184]

At this camp the sedentary, bored soldiery, if they had the money, could go to sutlers' shops where almost anything could be bought — wines, cigars, canned oysters[187] and even ladies' frocks. There were dentists, barbers, dance halls, a billiards saloon, brothels, bath houses, a church, even a theatre. For those in need of cash, the enterprising Baron of Mauá had opened a branch of his bank.[188] Small change was procured by cutting silver dollars into quarters with a cold chisel.[189] "The sutlers and camp-followers were the vilest of the vile", observed Burton, frequently murdering one another.[190]

On 3 November 1867, the Paraguayans attacked the camp with 9,000 infantry and cavalry, at first driving back the allied soldiers with considerable losses. The surprise attack caused panic. According to Thompson, López had given his soldiers permission to loot the camp,[191] which the nearly starving men proceeded to do, giving Porto Alegre time to rally his men and retaliate. Porto Alegre, who had two horses shot from under him, behaved with conspicuous courage; he turned the tide. The Paraguayans were driven from the camp, but they took vast amounts of plunder, and some prisoners and guns. This is known as the Second Battle of Tuyutí.[192]

While some historians have considered the result to be a draw, Professor Whigham had a different evaluation. López lost perhaps one third of his troops in this battle, which achieved practically nothing. It was a loss which he simply could not afford.[192] Such losses forced the Paraguayans to reduce their defensive perimeter around Humaitá and concentrate in its interior.[184]

"At the Battle of Tuyutí", wrote Thompson, "the [Uruguayan] army, which the day before numbered forty men and a general, was reduced to a general and twenty men".[193]

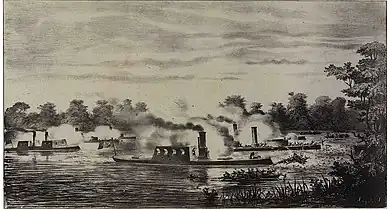

Passage of Humaitá; diversionary attacks

On 14 January 1868, cholera having killed the Vice-President of Argentina, Mitre left Paraguay for the last time to re-assume the presidency of his country. Caxias was now commander in chief without question.[40]

On 19 February 1868 six Brazilian ironclads at last summoned their resolution and dashed past the fortress of Humaitá. It turned out to be easier than they had thought, because they had sunk the chain boom and went by night. Nevertheless it caused a worldwide sensation. It restored the Brazilian Empire's financial credit and some authors have thought it was the turning point of the war.[lower-alpha 18]

To improve the navy's chances, a simultaneous diversionary attack was carried out by land. The allies opened fire with everything they had. Juan Crisóstomo Centurión, who was there, recalled:

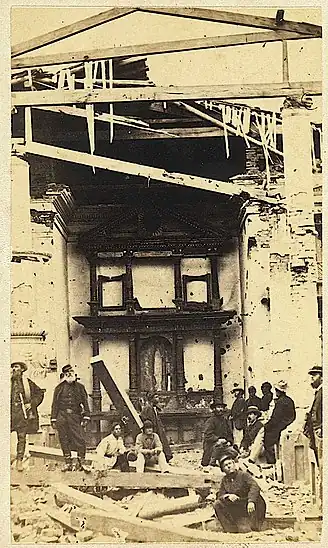

The immense allied encirclement around us spewed fire like a great volcano. Without interruption it launched bombs, solid shot, shells and rifle fire on our camp. It looked like a fantasy created by some poet, a theatrical exhibition! There was no need for such a fanfare [tanto aparato]. The naval operation was easy in itself, as events proved.[194]

Three of the ironclads, Bahia, Barroso and Rio Grande, steamed upriver, reaching Asunción on 22 February and bombarding it. López had ordered the city's population to be hastily evacuated already on 19 February and transferred the seat of government to Luque. Although the ironclads' bombardment was only a demonstration and did little material damage, it was the first time that the Paraguayan capital came under attack, which caused a psychological impact. The Palacio de los López, López's residence in Asunción, had one of its balconies destroyed.[195][196]

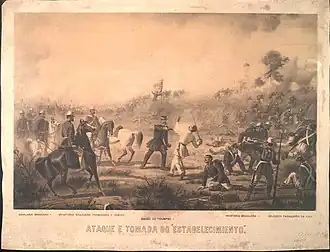

The capture of Estabelecimento

To coincide with the diversionary attack it was decided to capture a redoubt or small earthwork fort about 3,500 yards north of Humaitá, called "Estabelecimento novo" (by the Brazilians) or "Cierva" (by the Paraguayans). The allies thought it was an important military objective in its own right.

A Brazilian cavalry patrol, assisted by military engineers, had gone out to reconnoitre it. Their report said the installation was on the bank of the river. This was highly important: here was a landing place on the river Paraguay much nearer than Tayí. Not only could they draw the siege noose tighter — shortening their lines of communication — but they might send troops across to the Chaco to interdict the Paraguayan supply road. The fortress would now be totally cut off. Besides, surely such an elaborate installation must have been put there for a reason. It might be to protect a landing place for cattle.[197][198]

The installation (said the report) was held by only 50 men and some artillery, and could be approached from San Solano along a flat, dry road. It should be easy to hold indefinitely and there was good pasture nearby for the cavalry.

The report was highly misleading.

As the map shows Estabelecimento was not on the bank of the river Paraguay at all, but on the shores of a lagoon. What the reconnaissance party had seen, early in the morning and with the sun behind them, was not the river: it was the shimmering water of the lagoon.[199] In fact, said Thompson, the installation was a bluff. It never was of any use to Lopez; he had only built it to mystify the enemy.[200]

Misinformed, therefore, Caxias ordered a 7,000 man force, some equipped with Dreyse guns, to take Estabelecimento by storm, the attack to coincide with the naval passage of Humaitá. The site turned out to be well defended by a force of 500 men and 9 guns ensconced behind parapets. Wave after wave of attackers met a hail of grapeshot and canister. At last the Brazilians heard a Paraguayan soldier tell his officer their ammunition was exhausted. Encouraged, they seized the site. The defenders escaped in the Tacuarí and the Ygurey, which could steam into the lagoon through a small tributary called the Arroyo Hondo. The Brazilians sustained 1,200 casualties; the Paraguayans, 150.[201]

This incident demonstrated two things. First, how incomplete was the allies' knowledge of the local topography, even this late in the war.[83] Secondly, the high cost of storming entrenched artillery positions over open ground — as at Curupayty.

López escapes with the bulk of his army

With the passage of Humaitá and the capture of Estabelecimento, the allies further tightened the siege on the fortress.[202] Noticing the danger, López sent his long-term mistress Eliza Lynch and their children back to Asunción that same day.[203] He decided to escape Humaitá with a large portion of his army and head north to San Fernando. To reach it, however, he would need to cross the Paraguay River to the inhospitable Chaco and then cross back to the left bank, since Humaitá had been cut off by land and the river was blocked at Tayí. The escape route would be the road he had built in the Chaco.[202]

The Paraguayans attempt to seize two ironclads

Before leaving, however, López decided on a daring attack against the Brazilian ironclads; his goal was to take control of at least one of them, which were dispersed throughout the river. Five hundred men, called bogavantes, were selected for the task and given sabres and hand grenades; they also received training in swimming and boarding. On the night of 2 March 1868 they set out for the attack in canoes. The chosen target were the ironclads Cabral and Lima Barros, who laid anchored below Humaitá. The Brazilian watchmen who were in a guard boat saw the approaching Paraguayans and alerted the rest of their companions in the ironclads, but it was too late: a swarm of Paraguayans stormed the ships and took the Brazilians by surprise.[204]

The Paraguayans boarded the ships and killed the men who were sleeping topside to escape the heat inside the ironclads. Despite the initial surprise, the Brazilians managed to lock themselves inside the ironclads and retaliated with gunfire. The bogavantes vainly tried to break into the ships, striking their sabres against the iron doors; they also dropped grenades down the funnels, but most did not explode and the few that did caused only minimal damage. Upon becoming aware of what was happening, other Brazilian ships went to aid them. The first ironclad to the rescue was Silvado. Its skipper positioned it between Cabral and Lima Barros despite the danger of collision due to the pitch black night, and its crew opened a fire of grapeshot against the Paraguayans. The other vessels soon joined in. By the end of the fight many Paraguayans had been killed by gunfire, either on deck or trying to swim away. Most refused to surrender; only the badly wounded were captured. The attack had failed.[205][206]

The escape

Thus, having failed to capture an ironclad, López left Humaitá on the night of 3 March 1868 with twelve thousand of his soldiers;[202][207] he crossed the Paraguay River to Timbó, on the Chaco side.[166] He was followed soon after by generals Isidoro Resquín and Vicente Barrios with another ten thousand men.[202] López had ordered all the guns in the trenches surrounding Humaitá to be removed and sent to the fortress for transport to the Chaco, leaving only a few in Curupayty, Sauce and in the area between Angulo and Humaitá;[208][209] he also left Paulino Alén in command of the remaining garrison at Humaitá and Francisco Martínez as second in command.[207][210] The heavy artillery pieces had to be taken through the Chaco across deep streams; they were manhandled over improvised bridges. The sources do not explain how they were taken across the wide and rapidly flowing river Bermejo.[211]

The escape was possible because there were no Allied ships guarding the river between Humaitá and Timbó, to which López transported the artillery, provisions and men using his two steamers.[212] "Had the naval commanders left even one ironclad between Timbó and the fortress, its guns could have prevented López from escaping through the Chaco brush", wrote Whigham, but they "forgot" to plug the gap. Not all sources thus explain the omission; some have alleged that, later in the war, Caxias deliberately allowed López to escape.[213][146][214]

The gap was plugged on 22 March 1868[215][216] when, of the ironclads lying to the north of Timbó, two returned south — forcing the battery there — and found the Ygurey and Tacuarí at work. They sank the former; the latter, which was landing artillery (and was the only purpose-built warship in the Paraguayan navy), was scuttled to avoid capture. Not caring to repass the batteries of Humaitá, the ironclads sent down their reports in corked bottles. It was then that Resquín and Barrios escaped, fired upon by the ironclads.[217]

López had ordered Thompson to mount a battery at Monte Lindo.[218] He went north through the Chaco with his men and then crossed back to the left bank of the river, taking up a position in San Fernando, behind the Tebicuary River, where the Paraguayans built their new camp and defensive line.[219] López thought the wide and deep swamps along the Tebicuary would prevent the Allies from outflanking him from the east again as they had previously done with Humaitá.[220]

Final capture and destruction of Humaitá

Capture

News of López's escape reached the Allies on 11 March; it was deemed unsubstantiated at first. The Allies also did not know how many artillery and troops had escaped Humaitá.[221] To further close the siege, Caxias ordered general Argolo Ferrão, commander of the 2nd Army Corps, to attack and take Sauce; he also ordered generals Osório (commander of the 3rd Army Corps) and Gelly y Obes to capture Curupayty, Espinillo and Angulo, the main Paraguayan fortified positions south of the fortress. At that point these positions were weakly defended. The attacks took place on 21 March, with the Allies capturing the positions.[202] The next day the Paraguayans withdrew the rest of their units and artillery into Humaitá.[215]

Now that Humaitá had been isolated, Caxias had the option to starve it out or capture it by an assault after a previous artillery bombardment. This divided opinions among the Allies: some were against an assault for considering it too costly. Others held that the fortress should be immediately taken. Caxias chose the latter option.[222] In order to test Humaitá's strength, he ordered the navy and land artillery to bombard it throughout April.[221]

The Allies tried to persuade Paulino Alén to surrender by offering him material inducements, but he refused; desperate, he attempted suicide by gunshot on 12 July, wounding himself badly. He was replaced by Francisco Martínez.[223]

Since the surviving garrison of 2,000 men would not surrender — it was against their orders to do so — on 16 July 1868 Caxias ordered all the Allied land and naval artillery to bombard Humaitá.[224][225] The remaining Paraguayan garrison at the fortress did not fire back, which made Caxias believe it was empty; thus, he ordered Osório's 3rd Army Corps to reconnoitre and take the place by storm. They met yet another Paraguayan hailstorm of grapeshot and shrapnel. The attack was repelled with just over 1,000 casualties.[225]

Despite all the odds, the Paraguayans still had a tenuous line of communication with Humaitá from the north: rafts (or canoes) across the Chaco. To finish it off, Caxias dispatched general Ignacio Rivas, a Uruguayan-born serving in the Argentine army, with 2,000 men. This force had landed south of Timbó on 2 May and began searching for the Paraguayan trail. It was attacked by the Paraguayans, but managed to repel it after making contact with another 2,000 men strong Brazilian force. Rivas established himself in a ridge at a place called Andaí and cut off the Paraguayan telegraph lines he found there. The allies had begun to consolidate their position on the Chaco.[226]

The Paraguayans outside the fortress raided the Allies frequently.[227] López sent multiple requests to colonel Bernardino Caballero to carry out such raids. Caballero had built several redoubts between Timbó and Andaí and hoped to reopen the trail.[228] He did not have enough men for a frontal attack against the Allied position at Andaí, but envisioned he could trick Rivas into a trap.[228] Caballero's constant raids from his base at the Corá redoubt angered the Argentine general, who decided to attack it with a combined Argentine-Brazilian force on 18 July. The attack failed, with the Argentines suffering 400 casualties, including the death of colonel Miguel Martínez de Hoz, commander of the Rioja Battalion.[229]

The fortress' provisions had been exhausted at that point. Unable to resist any longer, Martínez, the Paraguayan commander, began to complete the evacuation of the fortress on the night of 24 July. People had been evacuated across the river to the Chaco in canoes since 11 July. In Whigham's estimation, "Since this departure was expected by the Allies, and since three more Brazilian ironclads had by now forced the batteries at Humaitá, it was shocking, almost criminal, that no one took note of the many trips taken across the river".[230]

On 25 July Martínez fired a 21-gun salute — it was López's birthday — and ordered the band to play music. Under cover of this ruse the rest of the men escaped the fortress and occupied Isla Poí. By next morning all the defenders had gone. Ten hours later, realising the fortress was empty, the allies occupied it at last.[231] Martínez and his men planned to join Caballero, who presumably was waiting for them on the Chaco. This time, however, the Allies were in position to block their escape.[232]

Surrender of the survivors

The territory in the Chaco opposite was a mixture of land, water and sandbars. Many evacuees (including the wounded colonel Alén carried in a stretcher) managed to escape in canoes at night through a lagoon that led north to near Timbó. The others had taken refuge on Isla Poí, a narrow spit of land and were under siege, since the allies by now had landed a very large force, commanded by general Rivas. It proceeded to bring a devastating fire against the survivors of Humaitá. Some defenders stood waist-deep in water; if wounded, they drowned.[233]

"The Paraguayans had eaten the last of their horses and now managed on berries and a little gun oil."[234] Burton inspected the scene not long afterwards: