Sigurd the Stout

Sigurd Hlodvirsson (c. 960 – 23 April 1014), popularly known as Sigurd the Stout from the Old Norse Sigurðr digri,[2] was an Earl of Orkney. The main sources for his life are the Norse Sagas, which were first written down some two centuries or more after his death. These engaging stories must therefore be treated with caution rather than as reliable historical documents.[3][Note 1]

Sigurd Hlodvirsson | |

|---|---|

| Earl of Orkney | |

| Title held | 991[1] to 1014 |

| Predecessor | Hlodvir Thorfinsson |

| Successor | Brusi, Sumarlidi and Einar Sigurdsson |

| Native name | Sigurðr digri - Sigurd the Stout |

| Died | 23 April 1014 Clontarf |

| Noble family | Norse Earls of Orkney |

| Spouse | Olith, daughter of Malcolm II of Scotland |

| Issue | Hunde, Brusi, Sumarlidi, Einar and Thorfinn |

| Father | Hlodvir Thorfinnsson |

| Mother | Eithne |

Sigurd was the son of Hlodvir Thorfinnsson and (according to the Norse sagas) a direct descendant of Torf-Einarr Rognvaldson. Sigurd's tenure as earl was apparently free of the kin-strife that beset some other incumbents of this title and he was able to pursue his military ambitions over a wide area. He also held lands in the north of mainland Scotland and in the Sudrøyar, and he may have been instrumental in the defeat of Gofraid mac Arailt, King of the Isles. The Annals of Ulster record his death at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, the earliest known reference to the earldom of Orkney.

The saga tales draw attention to Sigurd's conversion to Christianity and his use of a totemic raven banner, a symbol of the Norse God Odin. This ambiguous theme and the lack of detailed contemporary records of his life have led to a variety of interpretations of the saga material by modern scholars.

Sources

The sources for Sigurd's life are almost exclusively Norse sagas, none of which were written down at the time of the events they record. The Orkneyinga Saga was first compiled in Iceland in the early 13th century and much of the information it contains is "hard to corroborate".[6] Sigurd also appears briefly in St Olaf's Saga as incorporated into the Heimskringla and in the Eyrbyggja Saga. There are various tales about his exploits in the more fanciful Njal's Saga as well as the Saga of Gunnlaugr Serpent-Tongue, Thorstein Sidu-Hallsson's Saga, the Vatnsdæla Saga and in the tale of "Helgi and Wolf" in the Flateyjarbók.[7][8]

Family background

The Orkneyinga Saga reports that Sigurd was the son of Hlodvir, one of the five sons of Thorfinn Skull-Splitter, and Eithne. She is said to be a daughter of a "King Kjarvalr". The period after Earl Thorfinn's death was one of dynastic strife; three of Earl Hlodvir's brothers ruled before him, although he died in his bed before being succeeded by Sigurd,[9][10] probably in the 980s.[11]

Sigurd's patronymic is an unusual one and there would appear to be a connection with this name and the early roots of the modern French name "Louis".[12][Note 2]

Rule

Sigurd was in the fortunate position that on his accession to the earldom there seem to have been no other serious contenders. In this respect his rule was unlike that of the earlier generation of the sons of Earl Thorfinn and of the next generation in that it avoided the bitter feuding that beset the earldom during both of those periods.[2]

Sigurd's great-grandfather, Torf-Einarr, lost the udal rights of the Orkney and Shetland farmers as part of a deal he brokered with the Norwegian crown. These rights were restored by Sigurd.[15] The Burray hoard of silver ring-money has been dated to the period 997–1010, during Earl Sigurd's reign.[16]

Mainland Scotland

Sigurd's domain included not just Orkney itself but also Shetland, which formed part of the earldom and also extensive lands on mainland Scotland. For the latter his overlords were the Kings of Scotland rather than of Norway.[17] The extent of these mainland dominions is uncertain. According to the rather dubious source, Njal's Saga, they included Ross, Moray, Sutherland and the Dales. At the time Moray would have included districts on the west coast including Lochaber.[2] Smyth (1984) notes the density of dalr placenames on Scotland's west coast and it has even been suggested that "the Dales" is a reference to Dalriada, although it is more likely that it means Caithness.[2][18] During Sigurd's tenure the earldom approached its high point and his influence was perhaps only exceeded by that of his son Thorfinn.[2]

Sigurd's uncle Ljot had been killed in war against the Scots,[19] and Sigurd soon faced trouble from his southern neighbours. According to the Orkneyinga saga "Earl Finnleik" (Findláech of Moray) led an army against him which outnumbered Sigurd's forces by seven to one.[20] The saga then records Sigurd's mother's reply when he went to her for advice:

Had I thought you might live for ever I'd have reared you in my wool-basket. But lifetimes are shaped by what will be, not by where you are. Now, take this banner. I've made it for you with all the skill I have, and my belief is this: it will bring victory to the man it's carried before, but death to the one who carries it.[20]

The Raven banner worked just as Sigurd's mother said: he was victorious but three standard-bearers in succession were killed.[20]

A battle was fought between Norwegian forces and Malcolm II of Scotland at Mortlach c. 1005 which may have involved or been led by Sigurd. Although victory went to the Scots, the Norwegians had clearly spent some considerable time encamped in Moray and came equipped with a large fleet. However, Orcadian influence in this part of Scotland is likely to have been temporary and on other occasions, such as during his uncle Ljot's earldom, Scottish forces had pushed north into Caithness.[19][21]

The Hebrides

Sigurd the Stout also took control of the Hebrides,[23][24] and placed a jarl called Gilli in charge. Njal's Saga records an expedition that took place c. 980 in which Kari, Sigurd's bodyguard, plundered the Hebrides, Kintyre and "Bretland" (probably Strathclyde). On another occasion Kari sailed through The Minch in order to collect tribute from Gilli, whose base may have been either Colonsay or Coll.[18][21]

The Annals of Ulster record a raid by "the Danes" on Iona on Christmas Night in which the abbot and fifteen of the elders of the monastery were slaughtered and this may have been connected with the successful conquering of the Isle of Man by Sigurd and Gilli between 985 and 989.[21][25] Njal's Saga records a victory for Sigurd over Gofraid mac Arailt, King of the Isles with the former returning to Orkney with the spoils. The contemporary Annals of Ulster record a similar event in 987 although with the reverse outcome. Here it is claimed that 1,000 Norsemen were killed, among them the Danes who had plundered Iona.[26] Two years later Njal's Saga reports a second campaign in the southern Hebrides, Anglesey, Kintyre, Wales and a more decisive victory in Man. Irish sources report only the death of King Gofraid in Dál Riata, an event that Thomson (2008) ascribes to Earl Gilli's Gall-Ghàidheil forces.[26][Note 3]

The Eyrbyggja saga records the payment of silver tribute from Man to Sigurd, and, although this is a rather unreliable source, there is corroboration of such an event occurring in 989 in a Welsh source, with payment being made of a penny each from the local population to "the black host of the Vikings".[26] It has been suggested that the much later use of ounceland and pennyland assessments in the Gàidhealtachd may date from the time of Earl Sigurd and his sons.[29]

By 1004 the western isles' independence from Orkney had been re-asserted under Ragnal mac Gofraid, who died in that year. It is possible the rules overlapped, with Gilli's zone of influence to the north and Ragnal's to the south.[30] On Ragnal's death Sigurd re-asserted control, which he held until his own death a decade later[31][32] after which the islands may have been held by Håkon Eiriksson.[33]

Religion

According to the Orkneyinga saga, the Northern Isles were Christianised by King Olaf Tryggvasson in 995 when he stopped at South Walls on his way back to Norway from Dublin. The King summoned jarl Sigurd and said "I order you and all your subjects to be baptised. If you refuse, I'll have you killed on the spot and I swear I will ravage every island with fire and steel." Unsurprisingly, Sigurd agreed and the islands became Christian at a stroke.[34]

This tale is repeated in St Olaf's Saga, (although here Olaf lands at South Ronaldsay) as is a brief mention of Sigurd's son "Hunde or Whelp" who was taken as a hostage to Norway by King Olaf. Hunde was held there for several years before dying there. "After his death Earl Sigurd showed no obedience or fealty to King Olaf."[35]

Death and succession

The Orkneyinga Saga blandly reports that "five years after the Battle of Svolder" Earl Sigurd went to Ireland to support Sigtrygg Silkbeard and, after taking up the raven banner, was killed in a battle that took place on Good Friday.[36] (The chronology is slightly awry in that Sigurd's death is known to have taken place 14 years after Svolder.)[36]

Njal's Saga provides a little more detail, alleging that Gormflaith ingen Murchada prompted her son Sigtrygg into getting Sigurd to fight against her former husband, Brian Ború: "She sent him to Earl Sigurd to beg for help ... Then King Sigtrygg fared south to Ireland, and told his mother that the Earl had undertaken to come."[37]

The 12th-century Irish source, the Cogadh Gaedhil re Gallaibh, records the events of the Battle of Clontarf in 1014. The "foreigners and Leinstermen" were led by Brodir of the Isle of Man and Sigurd, and the battle lasted all day. Though Brian was killed in the battle, the Irishmen ultimately drove back their enemies into the sea, and Sigurd himself was killed.[36][38] His death is corroborated by the Annals of Ulster, which record that amongst the dead was "Siuchraid son of Loduir, iarla Innsi Orcc" (i.e. of Sigurd, son of Hlodvir, Earl of Orkney).[32] This is the earliest known contemporary reference to the earldom of Orkney.[39]

Sigurd left four sons: Brusi, Sumarlidi, Einar and Thorfinn, each of whom would also bear the title Earl of Orkney; the lands were initially divided amongst the three older brothers,[17] Thorfinn being only five years old at the time.[35] Thorfinn's mother is specifically stated to be a daughter of Malcolm II, the Norsemen's foe at Mortlach.[35][40]

Njal's Saga provides the names of various other relatives of Sigurd's. Havard, who was killed at Thraswick (the modern Freswick in Caithness) is referred to as his brother-in-law.[41] Sigurd is said to have given his sister Nereida (also called Swanlauga) in marriage to Earl Gilli.[42]

Issue

Sigurd is believed to have married twice, the name of his first wife is not recorded, however she is the mother of his four oldest sons:

- Sumarlidi, jointly Earl of Orkney with his brothers Brusi and Einar from 1014 until his death in 1018.

- Brusi, jointly Earl of Orkney with his brothers Sumarlindi and Einar from 1014 to 1018 and Einar until 1020. (died 1030/35)

- Einar, jointly Earl of Orkney with his brothers Sumarlindi and Brusi from 1014 to 1018 and Brusi until his own death in 1020.

- Hunde, predeceased his father, taken as a hostage in 995 by King Olaf of Norway, died several years later while in Olaf's custody.

Sigurd married second, Olith, youngest daughter of Malcolm II of Scotland, together they had one son:

- Thorfinn, Earl of Orkney, born c. 1009 and died c.1065.

Interpretations

Sigurd's earldom "exerted a magnetic attraction for high-born Icelanders" and inspired many tales of military prowess in their own family sagas.[2]

.jpg.webp)

"King Kjarvalr", Sigurd's supposed grandfather, appears as Kjarvalr Írakonungr in the Landnámabók and has been identified as Cerball mac Dúnlainge, King of Osraige who died in 888. There is clearly a chronological problem with Sigurd's mother being the daughter of a king who died more than 70 years before the death of his own grandfather, Earl Thorfinn. Furthermore, Thorstein "the Red" Olafsson (fl. late 9th century and Hlodvir's great-grandfather) was apparently married to a granddaughter of Kjarvalr. Woolf (2007) concludes that the saga writers may have confused this story about the provenance of Sigurd Hlodvirsson with one about Thorstein, a close ally of Sigurd Eysteinsson.[43][44]

Drawing on Adam of Bremen's assertion that Orkney was not conquered until the time of Harald Hardrada, who ruled Norway from 1043 to 1066, Woolf (2007) speculates that Sigurd may have been the first Earl of Orkney.[11] He also offers the hypothesis that the earldom was a created by the Danish king Harald Bluetooth, circa 980 rather than in the time of Harald Fairhair one hundred years earlier. He concludes that "If there were no earls in Orkney before Sigurð's time it might help to explain the islands' low profile in the annals since these, for the most part, record only the deaths of great men."[45] However, the absence of comment on this subject by Irish sources prior to Sigurd's death there is hardly surprising. Irish sources of the period were not well informed about and "not much concerned" with Orkney.[46][Note 4] Smyth (1984) is more sympathetic to the claims of the sagas and argues that Torf-Einarr "may be regarded as the first historical earl of Orkney".[48]

The conflict between Sigurd and Olaf Tryggvasson probably predates their chance meeting at Kirk Hope as the latter is known to have been raiding in the Sudrøyar during the period 991–94. His motives for a determined pursuit of Christian obedience are likely to have been essentially political rather than religious. His journey back to Norway was in order to bid for the kingship there, and securing a passive Orkney in advance of this was therefore greatly to his advantage.[40] Although Sigurd's marriage to an unnamed daughter of Malcolm of Scotland is mentioned in the Orkneyinga Saga immediately after the death of Hunde and the earl's consequent break with Olaf Tryggvasson, Thomson (2008) views this nuptial arrangement as a joint attempt by the Orcadians and Scots to align themselves against the "common threat from Moray" rather than as a slight to Norway.[40]

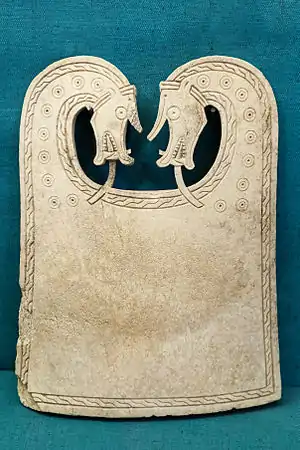

When the sagas were written down Orkney had been Christian for 200 years or more[49] and the conversion tale itself is "blatantly unhistorical".[50] When the Norse arrived in the Northern Isles they would have found organised Christianity already thriving there, although there is no mention of this at all in the sagas.[50] Furthermore, the Norse dragon motif of the whale-bone plaque found at the Scar boat burial was found in conjunction with the grave of an elderly woman who had died by 950 AD at the latest, and the weight of archaeological evidence suggests that Christian burial was widespread in Orkney by Sigurd's time.[51] The intention may have been to disown the influence of indigenous elements of Orcadian and Shetland culture and emphasise that positive cultural developments came from Scandinavia, whilst at the same time critiquing the unduly blunt method of Norwegian interference in this case.[50] The inclusion of the tale of the raven banner in the saga material may convey the idea of a revival of heathenism in Orcadian society and a reaction to Norwegian attempts to control the islands. However, in the Orkneyinga Saga there is a vivid contrast between Sigurd's death clutching the raven banner and the later career of his son Thorfinn, who is credited with several achievements in bringing Orkney into mainstream Christendom. Taken as a whole the intention may be to draw attention to this transition.[49]

References

Notes

- Alex Woolf, although critical of their historical value,[4] writes that by comparison with other source material the "Icelandic sagas appear more realist in style and seem to present a grittier image of the past that connects more easily with modern sensibilities" and of the Orkneyinga saga that "it is certainly a very good read".[5]

- Woolf (2007) states that "Sigurð's father would appear to have been the only Norseman to have borne this name [Hlöðvir] yet it is not unknown elsewhere in Norse literature."[12] For example, the name was given to Sigurd's son, Hunde, when he was baptised[13] and there is the use of "Hlöðvir" referring to the historical Frankish king Louis the Pious, son of Charlemagne.[14] Woolf presumably means that the name is not otherwise attested in Insular sources.

- Crawford (1987) also advances the connection between these "Danish" raids in Man and Earl Sigurd.[27] Etchingham (2001) examines the issue in detail and is more sceptical.[28]

- Contemporary documentation of this period of Scottish history is very weak. The presence of the monastery on Iona led to this part of Scotland being relatively well recorded from the mid-6th to the mid-9th century, but from 849 on, when Columba's relics were removed in the face of Viking incursions, written evidence from sources local to Argyll and the islands all but vanish for three hundred years.[47] Furthermore, Sigurd is the first of the Orkney earls to have any association with Ireland recorded by the Orkneyinga saga (excluding King Harald Finehair's disputed voyage to the west).

Footnotes

- Muir (2005) p. 27

- Thomson (2008) p. 59

- Woolf (2007) pp. 277–85

- Woolf (2007) p. 285

- Woolf (2007) p. 277

- Woolf (2007) p. 242

- Muir (2005) p. 28

- Thomson (2008) p. 66

- Orkneyinga Saga (1981) Chapters 9-11 pp. 33–36

- Ó Corrain, "Viking Ireland - Afterthoughts".

- Woolf (2007) p. 307

- Woolf (2007) p. 303

- Orkneyinga Saga (1981) Chapter 12 p. 37

- Norræna Fornfræðafélag (1828), Fornmanna sögur: eptir gömlum handritum, vol. 11, Kaupmannahofn, Prentaðar hjá H. F. Popp, p. 407

- Smyth (1984) p. 154

- Thomson (2008) p. 62

- Clouston (1918) p. 15

- Smyth (1984) p. 150

- Orkneyinga Saga (1981) Chapter 10 p. 36

- Orkneyinga Saga (1981) Chapter 11 pp. 36–37

- Thomson (2008) p. 60

- "Iona, St Martin's Cross. CANMORE. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- Hunter (2000) p. 84

- Ó Corráin (1998) p. 20

- Annals of Ulster. "U986.3". CELT. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- Thomson (2008) p. 61

- Crawford (1987) p. 66

- Etchingham (2001) pp. 177–79

- Thomson (2008) pp. 61–62

- Etchingham (2001) p. 181

- Gregory (1881) p. 5

- Woolf (2007) p. 243

- Woolf (2007) p. 246

- Thomson (2008) p. 69 quoting the Orkneyinga Saga chapter 12.

- Heimskringla. "Chapter 99 - History Of The Earls Of Orkney".

- Orkneyinga Saga (1981) Chapter 12 p. 38

- The Story of Burnt Njal (1861) "Chapter 153 - Kari goes abroad".

- Crawford (1987) p. 80

- Woolf (2007) p. 300

- Thomson (2008) p. 63

- The Story of Burnt Njal (1861) "Chapter 84 - Of Earl Sigurd".

- The Story of Burnt Njal (1861) "Chapter 88 - Earl Hacon fights with Njal's sons".

- Woolf (2007) pp. 283–84

- Crawford (1987) p. 54

- Woolf (2007) p. 308

- Thomson (2008) p. 25

- Woolf (2006) p. 94

- Smyth (1984) p. 153

- Thomson (2008) pp. 66–67

- Beuermann (2011) pp. 143–44

- Thomson (2008) p. 64

- General references

- Beuermann, Ian "Jarla Sǫgur Orkneyja. Status and power of the earls of Orkney according to their sagas" in Steinsland, Gro; Sigurðsson, Jón Viðar; Rekda, Jan Erik and Beuermann, Ian (eds) (2011) Ideology and power in the viking and middle ages: Scandinavia, Iceland, Ireland, Orkney and the Faeroes . The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 A.D. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. 52. Leiden. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-20506-2

- Clouston, J. Storer (1918) "Two Features of the Orkney Earldom". The Scottish Historical Review pp. 15–28. Edinburgh University Press/JSTOR. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- Crawford, Barbara E. (1987) Scandinavian Scotland. Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-7185-1197-2

- Etchingham, Colman (2001) "North Wales, Ireland and the Isles: the Insular Viking Zone". Peritia. 15 pp. 145–87

- DaSent, George W. (translator) (1861) The Story of Burnt Njal. Icelandic Saga Database. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- Gregory, Donald (1881) The History of the Western Highlands and Isles of Scotland 1493–1625. Edinburgh. Birlinn. 2008 reprint – originally published by Thomas D. Morrison. ISBN 1-904607-57-8

- Hunter, James (2000) Last of the Free: A History of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Edinburgh. Mainstream. ISBN 1-84018-376-4

- Muir, Tom (2005) Orkney in the Sagas: The Story of the Earldom of Orkney as told in the Icelandic Sagas. The Orcadian. Kirkwall. ISBN 0-9548862-3-2.

- Ó Corráin, Donnchadh (1998) Vikings in Ireland and Scotland in the Ninth Century CELT. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- Pálsson, Hermann and Edwards, Paul Geoffrey (translators) (1981). Orkneyinga Saga: The History of the Earls of Orkney. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044383-5

- Sturlson, Snorri Heimskringla. Wisdom Library. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- Smyth, Alfred P. (1984) Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80-1000. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-0100-7

- Thomson, William P. L. (2008) The New History of Orkney. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-84158-696-0

- Woolf, Alex "The Age of the Sea-Kings: 900–1300" in Omand, Donald (ed.) (2006) The Argyll Book. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-480-0

- Woolf, Alex (2007) From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070. Edinburgh. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1234-5