Simon Ganneau

Simon Ganneau[lower-alpha 1] (born circa 1805 in Lormes, died 14 March 1851 in Paris) was a French socialist, feminist, sculptor, and mystic.[1][2][3][4]

.jpg.webp)

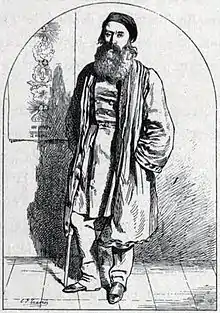

Simon Ganneau, le Mapah | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Contemporary caricature (1846) by Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard Grandville, preaching in front of a relief of masculine (sword, pipe) and feminine (corset, distaff) symbols. | |

| Born | circa 1805 Lormes, France |

| Died | 14 March 1851 Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

Like several other socialists of his time, Ganneau treated Christianity as a call for social reform.[3] He was influenced by Barthélemy Prosper Enfantin and Saint-Simonian philosophy,[2] particularly in viewing God as an androgynous or bisexual.[5] Ganneau's writings treat androgyny not only as a move towards religious salvation, the final stage of humanity, but also as embodying the socialist concept on unity and balance in the world.[2]

Adopting the title of the Mapah, a combination of mater and pater or maman and papa ("mother" and "father"), Ganneau presented himself as an androgynous prophet (with a beard and a woman's cloak)[6] of a new religion called "Evadaism" (French: Evadaïsme) based on his ideas for "a redefined humanity, Evadam" (from Eve-Adam) and for a new era of female emancipation, gender equality and social justice.[1][2][3][7] According to Éliphas Lévi, Ganneau also claimed to be the reincarnation of Louis XVII, and his wife claimed to be the reincarnation of Marie Antoinette.[6][8]

As a sculptor and a former phrenologist, he spread his ideas via pamphlets and plaster figurines, "of strange appearance, without doubt symbolically bisexual", both called "plasters".[2][3] His garret studio apartment on the Île Saint-Louis in Paris functioned in the late 1830s as a salon for discussing his ideas, and he influenced many of the socialists and feminists of his time, including Alexandre Dumas, Alphonse Esquiros, Flora Tristan and Éliphas Lévi (Abbé Constant).[2][3][9] Ganneau contributed to Tristan's 1844 collection The Worker's Union,[3] as well as to an 1848 paper titled La Montagne de la Fraternité.[2]

Ganneau had a wife[6] and child, who was five when Ganneau died in 1851, whom Théophile Gautier took under his wing: the Orientalist and archaeologist Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau.[4][10][11]

References

- Notes

- Also spelled Gannot or Gannau by some contemporaries, but always Ganneau by his closest followers.[1]

- Citations

- Julian Strube, Sozialismus, Katholizismus und Okkultismus im Frankreich des 9. Jahrhunderts: Die Genealogie der Schriften von Eliphas Lévi (2016), page 256

- Naomi Judith Andrews, Socialism's Muse: Gender in the Intellectual Landscape of French Romantic Socialism (2006), pages 40-41, 95, 102

- Susan Grogan, Flora Tristan: Life Stories (2002), pages 193-194

- Charles Nauroy (ed.), Le Curieux (1888), volume 2, page 239

- Sara E. Melzer, Leslie W. Rabine, Rebel Daughters: Women and the French Revolution (1992), page 284

- Gary Lachman, Revolutionaries of the Soul' (2014), page 43

- Francis Bertin, Esotérisme et socialisme (1995), page 53

- Éliphas Lévi, Histoire de la magie (Paris, Germer Baillière, 1860), pp. 519-525

- Stéphane Michaud, Flora Tristan - La Paria et son rêve (Paris, Presses Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2003), p. 110

- André Dupont-Sommer, "Un dépisteur de fraudes archéologiques : Charles Clermont-Ganneau (1846-1923), membre de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres", Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, April 1974, pp. 591-592

- Gustave Vapereau, Dictionnaire universel des contemporains, 5th edition (Paris, Hachette, 1880), p. 444

Further reading

- "Nouvelles ecclésiastiques", L'Ami de la religion, no. 2994, 17 July 1838; Baptême, Mariage (Paris, de Pollet, Soupe et Guillois, 1838)

- "Mort du créateur d'une religion nouvelle", A. Bonnetty, Annales de philosophie chrétienne, 4th series, (Paris, 1852), p. 164