Single Grave culture

The Single Grave culture (German: Einzelgrabkultur) was a Chalcolithic culture which flourished on the western North European Plain from ca. 2,800 BC to 2,200 BC.[1] It is characterized by the practice of single burial, the deceased usually being accompanied by a battle-axe, amber beads, and pottery vessels.[2] The Single Grave culture was a local variant of the Corded Ware culture, and appears to have emerged as a result of a migration of peoples from the Pontic–Caspian steppe. It was succeeded by the Bell Beaker culture, which according to the "Dutch model" appears to have been ultimately derived from the Single Grave culture. More recently, the accuracy of this model has been questioned.

| |

| Geographical range | Western North European Plain |

|---|---|

| Period | Chalcolithic |

| Dates | ca. 2,800–2,200 BC[1] |

| Preceded by | Corded Ware culture, Funnelbeaker culture, Pitted Ware culture |

| Followed by | Bell Beaker culture |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

History

Origins

The Single Grave culture was an offshoot of the Corded Ware culture, which was itself an offshoot of the Yamnaya culture of the Pontic–Caspian steppe. On the western North European Plain, the Single Grave culture replaced the earlier Funnelbeaker culture.[3]

Distribution

The Single Grave culture came to encompass the western part of the European Plain. In Denmark, Single Grave sites are concentrated in Jylland, where its appearance is accompanied by large-scale forest clearance and an expansion of animal husbandry, particularly cattle. In eastern Denmark, the Single Grave culture, the Pitted Ware culture, and the Funnelbeaker culture appear to have co-existed for some time.[4] It maintained close connections to other cultures of the Corded Ware horizon.

End

The Single Grave culture was succeeded by the Bell Beaker culture. According to the "Dutch Model," the Bell Beaker culture is thought to have been derived from the Protruding-Foot Beaker culture (PFB), which was a variant of the Single Grave culture.[5] More recently, this model has been questioned for its accuracy.[6]

Research

The term Single Grave culture was first introduced by the Danish archaeologist Andreas Peter Madsen in the late 1800s. He found Single Graves to be quite different from the already known dolmens, long barrows and passage graves.

In 1898, Danish archaeologist Sophus Müller was first to present a migration-hypothesis stating that previously known dolmens, long barrows, passage graves and newly discovered single graves may represent two completely different groups of people, stating "Single graves are traces of new, from the south coming tribes".[7]

Relative and absolute chronology

Frequent reburials in the mounds allow horizontal stratigraphic observations. In Jutland, three phases can be distinguished, which were originally proposed by Sophus Müller, verified by P. V. Glob and also by E. Hübner, who additionally verified the relative chronology in absolute time (calendar years). These phases are called under-grave, ground-grave, and upper-grave period.[8][9]

In the under-grave period, the graves are deepened into the soil. In the floor-grave period they are laid out at ground level. In the upper-grave period they are laid out above ground level. The Danish scholar P. V. Glob applied the observation that so-called A-axes can be placed early in the Lower Grave Period to the entire area of the Corded Ware. This led to the assumption of a simultaneous, common European A-horizon.[8][10] This has since been falsified.[11] However, the classification originally proposed by Glob has been verified, at least for Jutland and Schleswig-Holstein, and provided with absolute dates. The Younger Neolithic (YN) I corresponds to the Lower Grave Period (2850-2600 BC), the YN II to the Lower Grave Period (2600-2450 BC) and the YN III to the Upper Grave Period (2450-2250 BC).[9] For northern Germany this could be roughly verified, but not with the same accuracy.[12] The JN IIIb overlaps with the beginning of the Late Neolithic (also dagger period, Early Bronze Age in Central European terminology).

Characteristics

Burials

The Single Grave culture is known chiefly from its burial mounds. Thousands of such mounds have been discovered.[13] These are typically low, circular earthen mounds. Originally, the mounds were surrounded by a circle of split timbers. In low mounds, grave would contain one, or even two, plank coffins. Each coffin contained a single individual. Occasionally, new graves and mounds would be added on top of previous ones. Males were typically buried with battle axes, large amber discs and flint tools. Females were buried with amber necklaces made of small beads. Both genders were buried with a ceramic beaker. This probably contained some form of fermented beverage, possibly beer.[3]

Economy

The Single Grave people were engaged in animal husbandry, particularly the raising of cattle. They also engaged in agriculture, with barley as the main crop. Hunting and fishing also played a role, as numerous settlement finds in Jutland, Schleswig-Holstein, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and the Netherlands prove.[14]

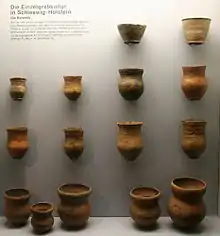

Pottery

The Single Grave people produced pottery with cord impressions similar to those of other cultures of the Corded Ware horizon. The cultural emphasis on drinking equipment already characteristic of the early indigenous Funnelbeaker culture, synthesized with newly arrived Corded Ware traditions. Especially in the west (Scandinavia and northern Germany), the drinking vessels have a protruding foot and define the Protruding-Foot Beaker culture (PFB) as a subset of the Single Grave culture.[15]

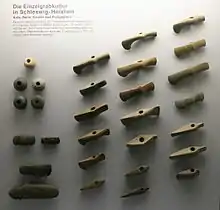

Battle axes

Many archaeological cultures are defined by their pottery and internally structured (typochronologically) by them. For the Single Grave Culture, however, the battle axes are to be regarded as the main item for structuring this archaeological culture chronologically. The battle axes form well differentiated types, which are also chronologically significant. In general, on the basis of Glob's study[8] and Hübner's[9] based on this, types A to L can be distinguished, in each case with several subtypes.

In the JN I, types A to F were used. The A1 axe is a form that is found supra-regionally and is referred to in many places as the A axe (or pan-European hammer axe). The A2 and A3 axes, on the other hand, are forms that occur almost exclusively in the area of the Single Grave culture; especially in Jutland, less so already in Schleswig-Holstein. Similarly, for most of the other forms of types B to L, it can be stated that the greatest variety and the most elaborated forms occur in Jutland. From here, the diversity decreases continuously.

In JN II, axes of the H, G and I variants were mainly used. The I axes are also referred to as boat axes because of their shape.

In JN III, mainly the K and L axes were used. The K-axes have shaft holes that are slightly to strongly offset towards the neck. This is a late development; prior to this, medium shaft holes predominated. Moreover, in the late Single Grave Culture (JN III acc. to Hübner), both very long and artistically designed battle axes (e.g. type K1) can be observed alongside very small and clumsy variants (K5).[9] This suggests that the importance of the battle axe is diversifying. This is further supported by the practice of integrating battle axes into multi-object hoards, which was not practised until late in the JN III.[14]

Contrary to established opinions, most battle axes are not known from burial contexts, but represent isolated finds.[14]

Genetics

In a genetic study published in Nature in June 2015, the remains of a Single Grave male buried in Kyndeløse, Denmark c. 2850 BC-2500 was examined. He was determined to be a carrier of the paternal haplogroup R1a1a1 and the maternal haplogroup J1c4.[16][17] Like other people of the Corded Ware horizon, he notably carried Western Steppe Herder (WSH) ancestry.[18]

A genetic study published in January 2021 examined the remains of individuals from the Single Grave culture in Gjerrild, Denmark. The male carried the paternal haplogroup R1b1 and maternal haplogroup K2a. The female carried mtDNA haplogroup HV0.[19] The remains are dated to c. 2500 BC.

See also

References

- Frei 2019.

- Davidsen 1978, p. 10.

- Price 2015, pp. 161–169.

- Price 2015, p. 160.

- Fokkens 1998, p. 105.

- Fokkens 2012.

- Trigger 1989, pp. 155–156.

- Glob 1944: P. V. Glob, Studier over den jyske Enkeltgravskultur. Aarbøger 1944.

- Hübner 2005: E. Hübner, Jungneolithische Gräber auf der Jütischen Halbinsel. Typologische und chronologische Studien zur Einzelgrabkultur. Nordiske Fortidsminder Serie B 24:1 (Kopenhagen 2005).

- Struve 1955: K. W. Struve, Die Einzelgrabkultur in Schleswig-Holstein und ihre kontinentalen Beziehungen. Offa-Bücher N. F. 11 (Neumünster 1955).

- Furholt, Martin (December 2014). "Upending a 'Totality': Re-evaluating Corded Ware Variability in Late Neolithic Europe". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 80: 67–86. doi:10.1017/ppr.2013.20. ISSN 0079-497X. S2CID 130766572.

- Brozio, Jan Piet (2019-11-22), Zur absoluten Chronologie der Einzelgrabkultur in Norddeutschland und Nordjütland [Supplement], heiDATA, doi:10.11588/data/hbavwg, retrieved 2021-10-05

- "The Single Grave Culture". National Museum of Denmark. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- Schultrich, Sebastian (2018-12-31). Das Jungneolithikum in Schleswig-Holstein. ISBN 978-90-8890-742-5.

- Fagan et al. 1996, pp. 89, 217.

- Allentoft et al. 2015, Supplementary Information, pp. 40-42, Supplementary Table 9, RISE61.

- Mathieson et al. 2018, Supplementary Table 1, Row 352, RISE61.

- Malmström et al. 2019, p. 6.

- Egfjord, Anne Friis-Holm; Margaryan, Ashot; Fischer, Anders; Sjögren, Karl-Göran; Price, T. Douglas; Johannsen, Niels N.; Nielsen, Poul Otto; Sørensen, Lasse; Willerslev, Eske; Iversen, Rune; Sikora, Martin (2021-01-14). "Genomic Steppe ancestry in skeletons from the Neolithic Single Grave Culture in Denmark". PLOS ONE. 16 (1): e0244872. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1644872E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0244872. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 7808695. PMID 33444387.

Sources

- Allentoft, Morten E.; et al. (June 10, 2015). "Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia". Nature. Nature Research. 522 (7555): 167–172. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..167A. doi:10.1038/nature14507. PMID 26062507. S2CID 4399103. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- Davidsen, Karsten (1978). The Final TRB Culture in Denmark: A Settlement Study. Akademisk Forlag. ISBN 9788750017967.

- Fagan, Brian M.; Beck, Charlotte; Michaels, George; Scarre, Chris; Silberman, Neil Asher (1996). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195076189.

- Fokkens, Harry (1998). Drowned Landscape: The Occupation of the Western Part of the Frisian-Drentian Plateau, 4400 BC-AD 500. Koninklijke Van Gorcum. ISBN 9789023233053.

- Frei, Karin Margarita (August 21, 2019). "Mapping human mobility during the third and second millennia BC in present-day Denmark". PLOS One. PLOS. 14 (8): e0219850. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1419850F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0219850. PMC 6703675. PMID 31433798.

- Fokkens, Harry (2012), "Background to Dutch Beakers. A critical review of the Dutch model" (PDF), in Fokkens, Harry; Nicolis, Franco (eds.), Background to Beakers. Inquiries in Regional Cultural Backgrounds of the Bell Beaker Complex, Sidestone Press

- Malmström, Helena; et al. (October 9, 2019). "The genomic ancestry of the Scandinavian Battle Axe Culture people and their relation to the broader Corded Ware horizon". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Royal Society. 286 (1912): 20191528. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.1528. PMC 6790770. PMID 31594508.

- Mathieson, Iain; et al. (February 21, 2018). "The genomic history of southeastern Europe". Nature. Nature Research. 555 (7695): 197–203. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..197M. doi:10.1038/nature25778. PMC 6091220. PMID 29466330.

- Price, T. Douglas (2015). Ancient Scandinavia: An Archaeological History from the First Humans to the Vikings. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190231972.

- Trigger, Bruce G. (1989). A History of Archaeological Thought. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521338189.