Sinus tachycardia

Sinus tachycardia is a sinus rhythm with an increased rate of electrical discharge from the sinoatrial node, resulting in a tachycardia, a heart rate that is higher than the upper limit of normal (90-100 beats per minute for adult humans).[1]

| Sinus tachycardia | |

|---|---|

| |

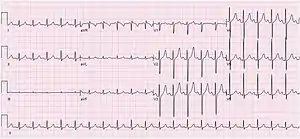

| ECG of a 29-year-old female with sinus tachycardia with a heart rate of 125 bpm | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

The normal resting heart rate is 60–90 bpm in an average adult.[2] Normal heart rates vary with age and level of fitness, from infants having faster heart rates (110-150 bpm) and the elderly having slower heart rates.[3] Sinus tachycardia is a normal response to physical exercise, when the heart rate increases to meet the body's higher demand for energy and oxygen, but sinus tachycardia can also indicate a health problem. Thus, sinus tachycardia is a medical finding that can be either physiological or pathological.[Note 1]

Signs and symptoms

Tachycardia is often asymptomatic. It is often a resulting symptom of a primary disease state and can be an indication of the severity of a disease.[4] If the heart rate is too high, cardiac output may fall due to the markedly reduced ventricular filling time.[5] Rapid rates, though they may be compensating for ischemia elsewhere, increase myocardial oxygen demand and reduce coronary blood flow, thus precipitating an ischemic heart or valvular disease.[4] Sinus tachycardia accompanying a myocardial infarction may be indicative of cardiogenic shock.

Cause

Sinus tachycardia is usually a response to physiological stress, such as exercise, or an increased sympathetic tone with increased catecholamine release, such as stress, fright, flight, and anger.[4] Other causes include:

- Pain[6]

- Fever[6]

- Anxiety[6]

- Dehydration[6]

- Malignant hyperthermia

- Hypovolemia with hypotension and shock

- Anemia[6]

- Hyperthyroidism[6]

- Mercury poisoning

- Kawasaki disease

- Pheochromocytoma

- Sepsis[6]

- Pulmonary embolism[6]

- Acute coronary ischemia and myocardial infarction

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Hypoxia

- Intake of stimulants such as caffeine, theophylline, nicotine, cocaine, or amphetamines[6]

- Hyperdynamic circulation

- Electric shock

- Drug withdrawal[6]

- Porphyria

- Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy

- Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome

- Mitral Valve Prolapse

- Metabolic Myopathies[7][8][9]

Diagnosis

Sinus tachycardia is usually apparent on an ECG, but if the heart rate is above 140 bpm the P wave may be difficult to distinguish from the previous T wave and one may confuse it with a paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia or atrial flutter with a 2:1 block. Ways to distinguish the three are:

- Vagal maneuvers (such as carotid sinus massage or Valsalva's maneuver) to slow the rate and identification of P waves

- administer AV blockers (e.g., adenosine, verapamil) to identify atrial flutter with 2:1 block

Heart sounds should also be listened to.[10]

ECG characteristics

Inappropriate sinus tachycardia

In inappropriate sinus tachycardia (also known as chronic nonparoxysmal sinus tachycardia), patients have an elevated resting heart rate and/or exaggerated heart rate in response to exercise. These patients have no apparent heart disease or other causes of sinus tachycardia. IST is thought to be due to abnormal autonomic control. IST is a diagnosis of exclusion.[11]

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome

Usually, in women with no heart problems, this syndrome is characterized by normal resting heart rate but exaggerated postural sinus tachycardia with or without orthostatic hypotension.

Metabolic myopathy

Upon exertion, sinus tachycardia can be seen in some inborn errors of metabolism that result in metabolic myopathies, such as McArdle Disease (GSD-V).[7] Metabolic myopathies interfere with the muscle's ability to create energy. This energy shortage in muscle cells causes an inappropriate rapid heart rate in response to exercise. The heart tries to compensate for the energy shortage by increasing heart rate to maximize delivery of oxygen and other blood borne fuels to the muscle cells.[7]

In one such category of metabolic myopathies, muscle glycogenoses (muscle GSDs), individuals are unable to create energy from muscle glycogen, and depending on the muscle GSD, may not be able to utilize blood glucose within the muscle cell either.[7] As skeletal muscle relies predominantly on glycogenolysis for the first few minutes as it transitions from rest to activity, as well as throughout high-intensity aerobic activity and all anaerobic activity, individuals with glycogenoses experience during exercise: sinus tachycardia, tachypnea, muscle fatigue and pain, during the aforementioned activities and time frames.[7][8] "In McArdle's, our heart rate tends to increase in what is called an 'inappropriate' response. That is, after the start of exercise it increases much more quickly than would be expected in someone unaffected by McArdle's."[9] Unique to McArdle Disease (GSD-V) is the phenomenon of second wind where after approximately 6–10 minutes of aerobic exercise, such as walking without an incline, the heart rate drops as blood borne fuels, predominantly from Free Fatty Acids, produce energy via oxidative phosphorylation.[7][8][12]

Rare diseases, such as McArdle disease, are often misdiagnosed.[7] "Ninety percent of people with GSD V received a misdiagnosis before a corrected diagnosis (GSD VII unknown), resulting in a median diagnostic delay of 29 years, which can seriously affect QoL [Quality of Life]… Of those who are misdiagnosed, 62% report being misdiagnosed more than once."[7] The inappropriate rapid heart rate in response to exercise may be misdiagnosed as inappropriate sinus tachycardia (which is a diagnosis of exclusion).

Treatment

Treatment for physiologic sinus tachycardia involves treating the underlying causes of the tachycardia response. Beta blockers may be used to decrease tachycardia in patients with certain conditions, such as ischemic heart disease and rate-related angina. In patients with inappropriate sinus tachycardia, careful titration of beta-blockers, salt loading, and hydration typically reduce symptoms. Patients who are unresponsive to such treatment can undergo catheter ablation to potentially repair the sinus node.[3]

Acute myocardial infarction

Sinus tachycardia can present in more than a third of the patients with AMI but this usually decreases over time. Patients with sustained sinus tachycardia reflects a larger infarct that are more anterior with prominent left ventricular dysfunction, associated with high mortality and morbidity. Tachycardia in the presence of AMI can reduce coronary blood flow and increase myocardial oxygen demand, aggravating the situation. Beta-blockers can be used to slow the rate, but most patients are usually already treated with beta-blockers as a routine regimen for AMI.

IST and POTS

Beta blockers are useful if the cause is sympathetic overactivity. If the cause is due to decreased vagal activity, it is usually hard to treat and one may consider radiofrequency catheter ablation.

Notes

- In this context, the adjectives physiological and pathological are opposites.

See also

- Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI)

- Inappropriate Sinus Tachycardia (IST)

- Metabolic Myopathies

- Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (PoTS)

- Second Wind (exercise phenomenon)

References

- Crawford, Michael H., ed. (2017). Current diagnosis & treatment cardiology (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 9781259641268. OCLC 973336660.

- MD, Howard E. LeWine (2011-12-21). "Increase in resting heart rate is a signal worth watching". Harvard Health. Retrieved 2022-04-05.

- Jameson, J. N. St C.; Dennis L. Kasper; Harrison, Tinsley Randolph; Braunwald, Eugene; Fauci, Anthony S.; Hauser, Stephen L; Longo, Dan L. (2005). Harrison's principles of internal medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division. pp. 1344–58. ISBN 978-0-07-140235-4.

- Lilly, Leonard S. Pathophysiology of heart disease: a collaborative project of medical students and faculty (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 9781469897585. OCLC 925544683.

- Emergency Care And Transportation Of The Sick And Injured. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2010. ISBN 978-1-4496-1589-5.

- Olshansky, Brian; Sullivan, Renee M (2018-06-19). "Inappropriate sinus tachycardia". EP Europace. 21 (2): 194–207. doi:10.1093/europace/euy128. PMID 29931244.

- Lucia A; Martinuzzi A; Nogales-Gadea G; Quinlivan R; Reason S; et al. (International Association for Muscle Glycogen Storage Disease study group) (28 October 2021). "Clinical practice guidelines for glycogen storage disease V & VII (McArdle disease and Tarui disease) from an international study group". Neuromuscul Disord (published December 2021). 31 (12): 1296–1310. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2021.10.006. PMID 34848128. (Erratum: PMID 35140027)

- Scalco RS; Chatfield S; Godfrey R; Pattni J; Ellerton C; Beggs A; Brady S; Wakelin A; Holton JL; Quinlivan R (July 2014). "From exercise intolerance to functional improvement: the second wind phenomenon in the identification of McArdle disease". Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 72 (7): 538–541. doi:10.1590/0004-282x20140062. PMID 25054987.

- Wakelin, Andrew (2017). Living With McArdle Disease (PDF). IAMGSD (International Association of Glycogen Storage Disease). p. 15.

- Allison Henning; Conrad Krawiec (2020). "Sinus Tachycardia". StatPearls. PMID 31985921.

- Ahmed A; Pothineni N; Charate R; et al. (June 2022). "Inappropriate Sinus Tachycardia: Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Management". J Am Coll Cardiol. 79 (24): 2450–2462. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.04.019. PMID 35710196.

- Salazar-Martínez E; Santalla A; Valenzuela PL; Nogales-Gadea G; Pinós T; Morán M; Santos-Lozano A; Fiuza-Luces C; Lucia A (15 October 2021). "The Second Wind in McArdle Patients: Fitness Matters". Front Physiol. 12 744632: 744632. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.744632. PMC 8555491. PMID 34721068.

- Hall, John E.; Guyton, Arthur C. (2000). Textbook of medical physiology. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-8677-6.

- Choudhury SR, Sharma A, Kohli V (February 2005). "Inappropriate sinus node tachycardia following gastric transposition surgery in children". Pediatric Surgery International. 21 (2): 127–8. doi:10.1007/s00383-004-1354-9. PMID 15654608. S2CID 39302980.

- Sinus tachycardia