Ewen Cameron of Lochiel

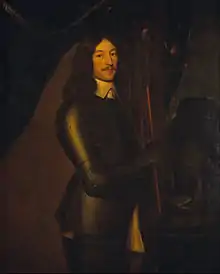

Sir Ewen Cameron of Lochiel (Scottish Gaelic: Eòghain Dubh Mac Dhòmhnaill Dubh; February 1629 – 12 June 1719) was a Scottish soldier and clan chief. He was Chief of the Clan Cameron—the 17th Lochiel—and renowned for his role as a Cavalier during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms in Scotland (1645–1658) and in the Jacobite rising of 1689. He is regarded as one of the most formidable Highland chiefs of all time.[2][3][4]

Sir Ewen Cameron of Lochiel | |

|---|---|

Sir Ewen Cameron, Laird of Lochiel | |

| Nickname(s) | Ulysses of the Highlands Eòghain Dubh ('Black Ewan') |

| Born | February 1629 Kilchurn Castle, Argyll, Scotland |

| Died | 12 June 1719 (aged 90) Achnacarry, Lochaber, Scotland |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1645–1689 |

| Relations | John Cameron, Lord Lochiel (son) Donald Cameron of Lochiel (grandson) |

Lord Macaulay described Lochiel as the "Ulysses of the Highlands".[5] An incident demonstrating his strength and ferocity in single combat, when he bit out the throat of an enemy,[6] inspired Sir Walter Scott's Lady of the Lake (canto v).[7] Among many legends, in 1680, Lochiel was said to have killed the last wolf in Scotland.[8][9][10]

Early years

Ewen Cameron of Lochiel was born in February 1629 at Kilchurn Castle, Loch Awe, the seat of his mother's family. He was the son of John Cameron, Master of Lochiel (died 1635) and Margaret Campbell, daughter of Sir Robert Campbell, 3rd Baronet, of Glenorchy.[7][11][12] He was the grandson of Allan Cameron of Lochiel, XVI Chief (c. 1567–1647), an elderly chief respected for many affrays.[13]

His father having predeceased him, Ewen was initially fostered by his brethren, the MacMartins of Letterfinlay, but then spent much of his youth as a hostage[14] of the Marquess of Argyll at Inveraray, by whose instruction he was tutored.[15] He was said to have been excessively fond of hunting, duelling and fencing—less inclined towards books—yet still bore great cunning and strength of mind.[16]

In 1647, he succeeded his grandfather as the chief of the Camerons, being one of the most important Highland clans.[6]

Appearance

Lord Lovat, who was at the court of Versailles, claimed that Lochiel bore a striking resemblance to Louis XIV, stating that "the resemblance was nearer than commonly that between two brothers; with this difference, that Sir Ewen was of a darker complexion, more brawny, and of a larger size". He was "unrivalled among the Celtic princes"—the Ulysses of the Highlands—according to Macaulay.[17]

James Philip of Almerieclos, a standard-bearer in the 1689 rebellion, authored the epic poem The Grameid in which he describes Lochiel's intimidating appearance and "Spanish countenance...with flashing eyes and a moustache curled as the moon horns".[18][19]

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

Legend of Montrose

The Camerons were always strong supporters of the Royal Stuarts. Ewen, Master of Lochiel witnessed the Battle of Inverlochy in 1645 during which his grandfather sent 300 highlanders to Montrose's aid, while he was forced to accompany Argyll.[20] That same year, he also witnessed Philiphaugh, the disastrous Royalist defeat. It is said that he developed Royalist sympathies after a secret meeting with Sir Robert Spottiswood on the eve of his execution by the Covenanters.[21] Furthermore, like many others, Lochiel was greatly inspired by James Graham, Marquis of Montrose.[19][22][20]

When Allan Cameron of Lochiel died in 1647, Lochiel finally left the clutches of Argyll and returned to his homeland of Lochaber, whence he was received joyously by his clansfolk. However Macdonald of Keppoch and Macdonald of Glengarry, thinking they could manipulate the novice Cameron chief, refused to pay their annual tribute to Lochiel who, in response, marched several hundred of his clansmen and forced the rebellious Macdonalds of Lochaber into submission.[23][24]

In April, 1650, Montrose was defeated at Carbisdale, betrayed, and shortly thereafter, hanged, drawn and quartered at Argyll's orders. Later that year, Lochiel received word from the exiled King Charles, requesting that he rally his men and join the Royalist army assembling at Stirling, whose defeat at Inverkeithing in 1651 led to Charles's fatal march to Worcester.[23]

Glencairn's Rising

Lochiel was present at a meeting of Scottish nobles at Lochearn in August, 1653, in which they elected to rebel against the Protectorate and restore the exiled King Charles to the throne. As such, he joined the army of William Cunningham, 9th Earl of Glencairn in the Royalist rising of 1653 to 1654, bringing with him several hundred Cameron warriors.[24]

At the Battle of Tullich on 10 February 1654, Lochiel was second-in-command to Glencairn and had the honour of commanding the outpost. He held the mountainous pass with his highlanders against the numerically superior forces of Robert Lilburne who was ultimately forced to retreat. He was personally commended by King Charles for his actions at Tullich, and hailed as the "deliverer of the Highland army".[25]

Further resistance

Lochiel continued fighting with Glencairn until 1654, when the latter was arrested for duelling and replaced in command by John Middleton. Among those involved in affrays was Lochiel's future father-in-law David Barclay, an officer serving under Middleton.[26] At the same time, George Monck became Governor of Scotland and kept the rebels hemmed in the Highlands. In a form of guerrilla warfare, Lochiel continued to resist for the next four years, becoming a paragon of Royalist resistance in the Highlands.[15][27]

A famous fight between Lochiel and a roundhead occurred during this period. He had encountered a group of English soldiers gathering firewood by Loch Eil, deep into Cameron territory, and in the ensuing fight Lochiel became separated from his men and grappled with an English officer who threw him onto his back, pinned to the ground and defenceless. Supposedly, Lochiel lunged at his victim's throat, biting down viciously and not letting go until he had torn out his windpipe for the 'sweetest bite ever he had'.[28][29][lower-alpha 1] He then proceeded to massacre a number of the garrison at Fort William and have their bodies mutilated and displayed as warning.[30]

Previously based at Tor Castle, Lochiel built a new seat at Achnacarry Castle in 1655 in order to keep his men further away from the government troops. It was only upon the death of Oliver Cromwell in 1658 that he did submit to general Monck and was received for his chivalrous conduct during the Civil War. Soon after, Lochiel accompanied Monck to London where the General called a meeting of Parliament to discuss the new status quo. After lengthy discussion and debate it was decided that the King would be invited back from exile and that the Royal House of Stuart would be restored to the throne after a Republican Interregnum period.

The Restoration

For his loyal service during the Civil War, Lochiel was received warmly by the newly-restored King Charles II in 1660, and later returned to his estates in Lochaber for a period of short-lived peace.

Highland feuds

Clan Cameron and Clan Mackintosh had been involved in a bitter, 360-year feud which began over the disputed lands of Loch Arkaig, Lochaber. On 20 September 1665, Lochiel ended this infamous feud with Clan Mackintosh after the stand-off at the Fords of Arkaig near Achnacarry.[31] After this, he was responsible for keeping the peace between his clansmen and their former enemies. However in 1668, whilst he was away at court in London, a feud broke out between Clan Donald and hostile elements of Clan Mackintosh, who headed the confederation of clans known as Clan Chattan. Lochiel’s clansmen made a significant contribution to the MacDonald victory against the Mackintosh’ at the Battle of Maol Ruadh (Mulroy), often considered to be the last clan battle.[32]

Among many legends, in 1680, Lochiel was said to have killed the last wolf in Scotland.[8][9][10]

The famous exploits of Lochiel were recited by Gaelic bards at his newly-built house of Achnacarry. One such bard described Achnacarry as "the generous house of feasting, pillared hall of princes, where wine goes round freely in gleaming glasses, music resounding under its rafters".[33] He became an acquaintance of James, Duke of York (later James VII and II).[34]

In 1681, Lochiel was knighted by the Duke of York. According to Balhaldie, after complimenting him on the successful outcome of his feud with the Mackintosh, he asked for Lochiel's sword, and attempted to draw it unsuccessfully; the Duke, after a second attempt gave it back to Lochiel and said "that his sword never used to be so uneasy to draw when the crown wanted his services". Lochiel unsheathed the sword and offered it to the Duke, who thereupon knighted him.[35][36]

Jacobite period

The Glorious Revolution was a disaster for Lochiel. In 1688, the Stuart King James VII and II was overthrown by William of Orange (In 1714, the Stuarts were then replaced by the Hanoverians). Lochiel, as a fervent Stuart loyalist, became one of the principal commanders in the Jacobite rising of 1689, having managed to rally a confederation of Highland clans loyal to that cause.

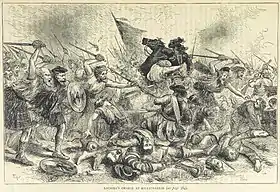

Commanding this force of highlanders, he fought alongside John Graham of Claverhouse, Viscount Dundee ("Bonnie Dundee") at the Battle of Killiecrankie – a stunning victory marred by Claverhouse’s death.[37] Alas, the Jacobite rebellion collapsed soon after as a result of arguments among the remaining leaders and the inept leadership of Alexander Cannon. By this time Sir Ewen, nearly sixty years old, had started to give his son John Cameron, Master of Lochiel greater responsibilities as he was unable to participate physically in military action. John Cameron led the clan for the remainder of the 1689 rebellion, and later also for the 1715 and 1719 risings. In 1717, he was made the Lord Lochiel in the Jacobite peerage by Prince James as recognition of his loyalty to the Jacobite cause.[35]

_-_Mary_of_Modena_(1658%E2%80%931718)%252C_Consort_of_James_VII_and_II_-_PG_976_-_National_Galleries_of_Scotland.jpg.webp)

Marriage and children

Sir Ewen married three times and had sixteen children. He married firstly the daughter of Macdonald of Sleat in a traditional Gaelic wedding ceremony of great splendour; she was said to have been very beautiful,[38] but died in 1657 without issue. His second wife was Isobel Maclean, daughter of Sir Lachlan Maclean, 1st Baronet, of Duart, and they had seven children. His final wife was Jean Barclay, daughter of David Barclay, Laird of Ury.[39]

Issue with Isobel Maclean:[40]

- John Cameron, 1st Lord Lochiel (1663–1747), succeeded as chief and was the father of Donald Cameron of Lochiel otherwise known as the Gentle Lochiel, who played an important role in the 1745 Jacobite rising[41]

- Major Donald Cameron of Clunes (died 1719), officer of the Dutch service who fought against his father at Killiecrankie

- Allan Cameron (died 1730), a Jacobite agent and courtier, married Isobel Fraser, daughter of Lord Lovat, and died in Rome

- Margaret Cameron, married Alexander MacGregor Drummond of Balhaldie, ephemeral chief of Clan Gregor

- Anne Cameron, married Allan Maclean, 10th of Ardgour

- Catherine Cameron, married William MacDonald of Boronaskittoch

- Janet Cameron, married John Grant of Glenmoriston

Issue with Jean Barclay:[42]

- James Cameron, died young

- Ludovic Cameron of Torcastle (died 1753), a Jacobite officer who fought alongside his nephew during the 1745 rising

- Christian Cameron, married Allan Cameron of Glendessary, mother of famed Jean Cameron of Glendessary[43]

- Jean Cameron, married Lachlan MacPherson, Chief of Clan MacPherson, and father of Cluny MacPherson

- Isobel Cameron, married Archibald Cameron of Dungallon

- Lucia Cameron, married Patrick Campbell of Barcaldine

- Ket Cameron, married to John Campbell of Achalader

- Una Cameron, married her cousin Robert Barclay of Ury (1732–1797)[44]

- Marjory Cameron, married Allan MacDonald of Morar

Death

Sir Ewen died of natural causes in 1719 at the age of ninety. He was buried with great ceremony at an ancient burial ground on the shores of Loch Eil. It was reported that thousands of Gaels and thirteen pipers gathered to his funeral.[45]

In literature

- The Lady of the Lake (canto v.), by Sir Walter Scott models the legendary fight of Lochiel and the roundhead for the fight scene between Roderick Dhu and FitzJames.

- Tales of a Grandfather, by Sir Walter Scott reproduced the apparent senility of Lochiel, who according to Thomas Pennant, "outlived himself, becoming a second child and even rocked in a cradle", juxtaposing this state with the great warrior of his youth.[34]

- The Grameid, an epic poem in Latin on the Claverhouse campaign of 1689 features Lochiel, written by James Philip of Almerieclos.

- The Jacobite Trilogy, a series of historical novels by D.K. Broster which focuses on the Cameron role in the 1745 rising.

Notes

- see Canto V, The Lady of the Lake

References

- "Ewan Cameron ancient burial mound at Loch Eil".

- "Remembering Sir Ewen Cameron of Lochiel - The Ulysses of the Highlands". The Oban Times. 11 November 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- MacPherson, Hamish (6 July 2021). "Clan Cameron: The origins and rise of the mighty Scottish clan". The National. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Stewart of Ardvorlich 1974, p. 84.

- Macaulay 1856, p. 252.

- Chisholm 1911.

- The Living Age. Vol. 175. 1887. p. 547.

- Shoberl, Frederic (1834). Natural History of Quadrupeds. J. Harris.

- Lovat-Fraser, James A. (March 1896). "The Wolf in Scotland". The Antiquary. 32: 75–76. ProQuest 6681122.

- Weymouth, Adam (21 July 2014). "Was this the last wild wolf of Britain?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Henderson 1886, p. 290.

- Stewart of Ardvorlich 1974, p. 56.

- Stewart of Ardvorlich 1974, p. 57.

- "Clan Cameron: Another Account of the Clan". www.electricscotland.com. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

- Sir Ewen Cameron, of Lochiel, 17th Chief of Clan Cameron. Clan Cameron Australia (Robert Cameron). 1996–2004. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- Drummond 1842, p. 24.

- Macaulay 1856, p. 251.

- Philip, James; Murdoch, Alexander Drimmie (1888). The Grameid: an heroic poem descriptive of the campaign of Viscount Dundee in 1689 and other pieces. Edinburgh: Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society. p. 130.

- Gibson, John S. (2019). Lochiel of the '45: The Jacobite Chief and the Prince. Edinburgh University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-4744-6845-9.

- Stewart of Ardvorlich 1974, p. 57–58.

- Drummond 1842, p. 30.

- The Living Age. 1887. p. 544.

Lochiel was by natural bent a cavalier. In secret, Montrose had long been his hero

- Stewart of Ardvorlich 1974, p. 59.

- The Living Age. 1887. p. 545.

- Stewart of Ardvorlich 1974, p. 60.

- Manganiello, Stephen C. (2004). The concise encyclopedia of the revolutions and wars of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1639 - 1660. Scarecrow Press. pp. 223–225. ISBN 978-0-8108-5100-9.

- MacKenzie 2008.

- Drummond of Balhaldie, John (1842). Memoirs of Sir Ewen Cameron of Locheill. Alpha Editions. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-150-68183-7.

- Wiseman, Andrew (17 April 2013). "The Calum Maclean Project: The Sweetest Bite: Cameron of Lochiel and the English Officer". The Calum Maclean Project. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- Stewart of Ardvorlich 1974, p. 63–64.

- MacKenzie 2008, p. 156.

- The Battle of Mulroy, clan-cameron.org. Accessed 28 December 2022.

- Stewart of Ardvorlich 1974, p. 83–84.

- Stewart of Ardvorlich 1974, p. 340–345.

- "Ewen Cameron of Lochiel". galton.org. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- Drummond 1842.

- "Scotland Back in the Day: Victory and death – the story of Bonnie Dundee". The National. 25 October 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

- The Living Age. 1887. p. 549.

- Stewart of Ardvorlich 1974, p. 82.

- De la Caillemotte de Massue de Ruvigny, Melville Amadeus Henry Douglas Heddle (1904). The Jacobite Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Grants of Honour. p. 97.

- Stewart of Ardvorlich 1974, p. 89.

- Stewart of Ardvorlich 1974, p. 85.

- Stewart of Ardvorlich 1974, p. 83.

- "BARCLAY ALLARDICE, Robert (1732–97), of Urie, Kincardine. | History of Parliament Online". www.historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- "Final resting place of revered clan chief discovered". www.scotsman.com. 11 February 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

Bibliography

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cameron of Lochiel, Sir Ewen". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Drummond, John (1842). Memoirs of Sir Ewen Cameron of Locheill. Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club.

- Furgol, Edward M. "Cameron, Sir Ewen, of Lochiel (1629–1719)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4440. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Henderson, Thomas Finlayson (1886). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 8. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Macaulay, Thomas Babington (1856). The History of England from Accession of James II. Harper & Brothers.

- MacKenzie, Alexander (2008). "The History of the Camerons". The Celtic Magazine. Vol. 9, no. 97. ISBN 978-0-559-79382-0. Modern reprint of November 1883 article with a detailed account of Sir Ewen's life from 1654 to 1665.

- Stewart of Ardvorlich, John (1974). The Camerons: A History of Clan Cameron. Edinburgh: Clan Cameron Association. ISBN 978-0950555102.

Further reading

- Memoirs of Sir Ewen Cameron of Locheill, by John Drummond of Balhaldie (Bannatyne Club, 1842)