Kingsley Wood

Sir Howard Kingsley Wood (19 August 1881 – 21 September 1943) was a British Conservative politician. The son of a Wesleyan Methodist minister, he qualified as a solicitor, and successfully specialised in industrial insurance. He became a member of the London County Council and then a Member of Parliament.

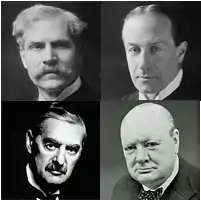

Sir Kingsley Wood | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |

| In office 12 May 1940 – 21 September 1943 | |

| Prime Minister | Winston Churchill |

| Preceded by | Sir John Simon |

| Succeeded by | Sir John Anderson |

| Lord Privy Seal | |

| In office 3 April 1940 – 12 May 1940 | |

| Prime Minister | Neville Chamberlain |

| Preceded by | Samuel Hoare |

| Succeeded by | Clement Attlee |

| Secretary of State for Air | |

| In office 16 May 1938 – 3 April 1940 | |

| Prime Minister | Neville Chamberlain |

| Preceded by | Philip Cunliffe-Lister |

| Succeeded by | Sir Samuel Hoare |

| Minister of Health | |

| In office 7 June 1935 – 16 May 1938 | |

| Prime Minister | Stanley Baldwin Neville Chamberlain |

| Preceded by | Hilton Young |

| Succeeded by | Walter Elliot |

| Postmaster General | |

| In office 25 August 1931 – 7 June 1935 | |

| Prime Minister | Ramsay MacDonald Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by | William Ormsby-Gore |

| Succeeded by | George Tryon |

| Member of Parliament for Woolwich West | |

| In office 14 December 1918 – 21 September 1943 | |

| Preceded by | Office Created |

| Succeeded by | Francis Beech |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Howard Kingsley Wood 19 August 1881 Kingston-Upon-Hull, England |

| Died | 21 September 1943 (aged 62) London, England |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouse |

Agnes Lilian (m. 1905) |

| Children | 1 daughter |

Wood served as junior minister to Neville Chamberlain at the Ministry of Health, establishing a close personal and political alliance. His first cabinet post was Postmaster General, in which he transformed the British Post Office from a bureaucracy to a business. As Secretary of State for Air in the months before the Second World War he oversaw a huge increase in the production of warplanes to bring Britain up to parity with Germany. When Winston Churchill became Prime Minister in 1940, Wood was made Chancellor of the Exchequer, in which post he adopted policies propounded by John Maynard Keynes, changing the role of HM Treasury from custodian of government income and expenditure to steering the entire British economy.

One of Wood's last innovations was the creation of Pay As You Earn, under which income tax is deducted from employees' current pay, rather than being collected retrospectively. This system remains in force in Britain. Wood died suddenly on the day on which the new system was to be announced to Parliament.

Early years

Wood was born in Hull, eldest of three children of the Rev. Arthur Wood, a Wesleyan Methodist minister, and his wife, Harriett Siddons, née Howard.[1] His father was appointed to be minister of Wesley's Chapel in London, where Wood grew up, attending nearby Central Foundation Boys' School.[2][3] He was articled to a solicitor, qualifying in 1903 with honours in his law examinations.[4]

In 1905 Wood married Agnes Lilian Fawcett (d. 1955); there were no biological children of the marriage, but the couple adopted a daughter.[3] Wood established his own law firm in the City of London, specialising in industrial insurance law. He represented the industrial insurance companies in their negotiations with the Liberal government before the introduction of Lloyd George's National Insurance Bill in 1911, gaining valuable concessions for his clients.[1]

Wood was first elected to office as a member of the London County Council (LCC) at a by-election on 22 November 1911, representing the Borough of Woolwich for the Municipal Reform Party.[1] His importance in the field of insurance grew over the next few years; his biographer Roy Jenkins has called him "the legal panjandrum of industrial insurance".[3] He chaired the London Old Age Pension Authority in 1915 and the London Insurance Committee from 1917 to 1918, was a member of the National Insurance Advisory Committee from 1911 to 1919, chairman of the Faculty of Insurance from 1916 to 1919 and president of the faculty in 1920, 1922 and 1923.[1] At the LCC he was a member of the council committees on insurance, pensions and housing.[3] He was knighted in 1918 at the unusually early age of 36. It was not then, as it later became, the practice to state in honours lists the reason for the conferring of an honour,[5] but Jenkins writes that Wood's knighthood was essentially for his work in the insurance field.[3]

Member of Parliament

Wood was elected to Parliament as a Conservative in the "khaki election" of 1918. His constituency, Woolwich West, was marginal, but he represented it for the rest of his life.[3] Before being elected, he had attracted notice by advocating the establishment of a Ministry of Health;[1] after the election he was appointed Parliamentary Private Secretary (an unpaid assistant to a minister, a traditional first rung on the political ladder) to the first Minister of Health, Christopher Addison.[3]

After the collapse of the coalition government in 1922, Wood was offered no post in the Conservative government formed by Bonar Law.[1] As a backbencher, Wood successfully introduced the Summer Time Bill of 1924. This measure, passed in the teeth of opposition from the agricultural lobby, provided for a permanent annual summer time period of six months from the first Sunday in April to the first Sunday in October.[6]

When Baldwin succeeded Law in 1924, Wood was appointed Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Health, as junior minister to Neville Chamberlain. The two served at the Ministry of Health from 11 November 1924 to 4 June 1929, becoming friends and firm political allies.[1] They worked closely together on local government reform, including a radical updating of local taxation, the "rates", based on property values.[7] Wood's political standing was marked by his appointment as a civil commissioner during the general strike of 1926,[1] and, unusually for a junior minister, as a privy councillor in 1928.[8] In 1930 he was elected as the first chairman of the executive committee of the National Union of Conservative and Unionist Associations.[1]

When the National Government was formed by Ramsay MacDonald in 1931, Wood was made Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Education. After the general election of November 1931 he was promoted to the office of Postmaster General.[8] The position did not entail automatic membership of the cabinet, but Wood was made a cabinet member in 1933.

Ministerial service

As minister in charge of the General Post Office (GPO), Wood inherited an old-fashioned organisation, not equipped to meet the needs of the 1930s. In particular its management of the national telephone system, a GPO monopoly, was widely criticised.[1] Wood considered reconstituting the whole of the GPO, changing it from a government department to what would later be called a quango, and he set up an independent committee to advise him on this. The committee recommended that the GPO should remain a department of state, but adopt a more commercial approach.[8]

Under Wood the GPO introduced reply paid arrangements for businesses,[9] and set up a national teleprinter service.[10] For the telephone service, still mostly dependent on manual operators, the GPO introduced a programme of building new automated exchanges.[11] For the postal service, the GPO built up a large fleet of motor vehicles to speed delivery, with 3,000 vans and 1,200 motor-cycles.[12] Wood was a strong believer in publicity; he set up an advertising campaign for the telephone system which dramatically increased the number of subscribers, and he established the GPO Film Unit which gained a high aesthetic reputation as well as raising the GPO's profile.[13] Most importantly, Wood transformed the senior management of the GPO and negotiated a practical financial deal with HM Treasury. The civil service post of Secretary to the Post Office was replaced by a director general with an expert board of management. The old financial rules, by which all the GPO's surplus revenue was surrendered to the Treasury had long prevented reinvestment in the business; Wood negotiated a new arrangement under which the GPO would pay an agreed annual sum to the Treasury and keep the remainder of its revenue for investment.[1]

When MacDonald was succeeded as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom by Baldwin in 1935, Wood was appointed Minister of Health. Despite its title, the Ministry was at that time at least as concerned with housing as with health. Under Wood, his biographer G. C. Peden writes, "the slum clearance programme was pursued with energy, and overcrowding was greatly reduced. There was also a marked improvement in maternal mortality, mainly due to the discovery of antibiotics able to counteract septicaemia, but also because a full-time, salaried midwifery service was created under the Midwives Act of 1936."[1] Jenkins comments that the housing boom of the 1930s was one of the two main contributors to such economic recovery as there was after the Great Depression.[13]

When Anthony Eden resigned from Chamberlain's government in March 1938, Wood moved to be Secretary of State for Air in the ensuing reshuffle. The UK was then producing 80 new warplanes a month. Within two years under Wood the figure had risen to 546 a month.[14] By the outbreak of the Second World War, Britain was producing as many new warplanes as Germany.[1] Wood's tenure as Secretary of State for Air coincided with the Phoney War, and during this time he limited RAF activity to dropping propaganda leaflets rather than strategic bombing. When Leo Amery urged him to destroy the Black Forest with incendiary bombs in reaction to the invasion of Poland, he is said to have replied "Are you aware it is private property?... Why, you will be asking me bomb Essen next!"[15] By early 1940, Wood was worn out by his efforts, and Chamberlain moved him to the non-departmental office of Lord Privy Seal, switching the incumbent, Sir Samuel Hoare, to the Air Ministry in Wood's place. Wood's job was to chair both the Home Policy Committee of the cabinet, which considered "all social service and other domestic questions and reviews proposals for legislation" and the Food Policy Committee, overseeing "the problems of food policy and home agriculture".[16] He held this position for only a few weeks; the downfall of Chamberlain affected Wood in an unexpected way.

In May 1940, as a trusted friend, Wood told Chamberlain "affectionately but firmly" that after the debacle of the British defeat in Norway and the ensuing Commons debate, his position as Prime Minister was impossible and he must resign.[17] He also advised Winston Churchill to ignore pressure from those who wanted Lord Halifax, not Churchill, as Chamberlain's successor.[1] Chamberlain agreed to resign on 9 May, but considered going back on his decision the next day as the German attack on the Western Front had begun; Wood told him that he had to go through with his resignation.[17] Both men acted on Wood's advice. Churchill became Prime Minister on 10 May 1940; Wood was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer on 12 May.[18]

Chancellorship of the Exchequer and death

One of the reasons for Wood's appointment to the Treasury seems to have been Churchill's urgent desire to be rid of the incumbent Chancellor of the Exchequer, Sir John Simon, whom Churchill detested.[17] Another may have been Wood's record of working well with politicians from other parties.[19] In peacetime, the Chancellor of the Exchequer is often the most important member of the cabinet after the Prime Minister,[17] but the exigencies of the war reduced the Chancellor's precedence. The Treasury temporarily ceased to be the core department of government. In Peden's words, "Non-military aspects of policy, including economic policy, were co-ordinated by a cabinet committee … The Treasury's main jobs were to finance the war with as little inflation as possible, to conduct external financial policy so as to secure overseas supplies on the best possible terms, and to take part in planning for the post-war period."[1]

Wood was Chancellor, as Jenkins notes, "for the forty key months of the Second World War".[20] He presented four budgets to Parliament. His first, in July 1940, passed with little notice, and brought into effect some minor changes planned by his predecessor. Of more long-lasting impact was his creation in the same month of a council of economic advisers, the most notable of whom, John Maynard Keynes, was quickly recruited as a full-time adviser at the Treasury. Jenkins detects Keynes's influence in Wood's second budget, in April 1941.[21] It brought in a top income tax rate of 19s 6d (97½ pence in decimal currency) and added two million to the number of income tax payers; for the first time in Britain's history the majority of the population was liable to income tax.[21] Keynes convinced Wood that he should abandon the orthodox Treasury doctrine that Chancellors' budgets were purely to regulate governmental revenue and expenditure; Wood, despite some misgivings on Churchill's part, adopted Keynes's conception of using national income accounting to control the economy.

With the hugely increased public expenditure necessitated by the war – it increased sixfold between 1938 and 1943 – inflation was always a danger.[21] Wood sought to head off inflationary wage claims by subsidising essential rationed goods, while imposing heavy taxes on goods classed as non-essential.[1] The last change he pioneered as Chancellor was the system of Pay As You Earn (PAYE), by which income tax is deducted from current pay rather than paid retrospectively on past years' earnings.[22] He did not live to see it come into effect; he died suddenly at his London home on the morning of the day on which he was due to announce PAYE in the House of Commons.[22] He was 62.

Wood was referred to in the book Guilty Men by Michael Foot, Frank Owen and Peter Howard (writing under the pseudonym "Cato"), published in 1940 as an attack on public figures for their failure to re-arm and their appeasement of Nazi Germany.[23]

Notes

- Peden, G. C. "Wood, Sir (Howard) Kingsley (1881–1943)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edition, May 2006.

- "Alumni". Central Foundation Boys' School. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- Jenkins, p. 394

- "The Law Society", The Times, 23 May 1903, p. 5

- "New Year Honours – The Official Lists", The Times, 1 January 1918, p. 7

- "'Summer Time' for Six Months", The Times, 31 January 1924, p. 14

- "Rating Reform – New Bill in the Commons", The Times, 14 May 1925, p. 16

- Jenkins, p. 395

- "Business Reply Cards – Post Office Innovation", The Times, 18 February 1932, p. 9

- "Teleprinters – Post Office Arrangements for Lease", The Times, 1 March 1932, p. 13

- "Four Exchanges in One – New London Telephone Building Opened", The Times, 9 November 1932, p. 6

- "The Post Office in 1933 – Sir Kingsley Wood on New Projects", The Times, 3 January 1933, p. 15

- Jenkins, p. 396

- Jenkins, pp. 396–397

- Bouverie, Tim (2019). Appeasement: Chamberlain, Hitler, Churchill, and the Road to War (1 ed.). New York: Tim Duggan Books. pp. 380-381. ISBN 978-0-451-49984-4. OCLC 1042099346.

- "A Reshuffle of the Government – Ministers Exchange Offices", The Times, 4 April 1940, p. 8

- Jenkins, p. 587

- "Names of New Ministers – Key Posts for Opposition – Sir K. Wood at the Exchequer", The Times, 13 May 1940, p. 6

- Jenkins pp. 394–396

- Jenkins, p. 393

- Jenkins, p. 399

- Jenkins, p. 400

- Cato (1940). Guilty men. London: V. Gollancz. OCLC 301463537.

References

- Jenkins, Roy (1998). The Chancellors. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-73057-7.

- Gault, Hugh (2014). Making the Heavens Hum Part 1: Kingsley Wood and the Art of the Possible 1881-1924. Cambridge: Gretton Books. ISBN 978-0-9562041-7-2.

- Gault, Hugh (2017). Making the Heavens Hum Part 2: Scenes from a Political Life: Kingsley Wood 1925-1943. Cambridge: Gretton Books. ISBN 978-0-9562041-9-6.

_(2022).svg.png.webp)