Redvers Buller

General Sir Redvers Henry Buller, VC, GCB, GCMG (7 December 1839 – 2 June 1908) was a British Army officer and a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces. He served as Commander-in-Chief of British Forces in South Africa during the early months of the Second Boer War and subsequently commanded the army in Natal until his return to England in November 1900.

Redvers Buller | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 7 December 1839 Crediton, Devon |

| Died | 2 June 1908 (aged 68) Crediton, Devon |

| Buried | Holy Cross Churchyard, Crediton |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ | British Army |

| Years of service | 1858–1901 |

| Rank | General |

| Unit | King's Royal Rifle Corps |

| Commands held | Aldershot Command British Forces in South Africa Adjutant-General to the Forces Quartermaster-General to the Forces |

| Battles/wars | Second Anglo-Chinese War Anglo-Ashanti wars Xhosa Wars Anglo-Zulu War First Boer War Anglo-Egyptian War Mahdist War Second Boer War |

| Awards | |

Origins

Buller was the second son and eventual heir of James Wentworth Buller (1798–1865), MP for Exeter, by his wife Charlotte Juliana Jane Howard-Molyneux-Howard (d.1855), third daughter of Lord Henry Thomas Howard-Molyneux-Howard, Deputy Earl Marshal and younger brother of Bernard Howard, 12th Duke of Norfolk. Redvers Buller was born on 7 December 1839 at the family estate of Downes, near Crediton in Devon, inherited by his great-grandfather James Buller (1740–1772) from his mother Elizabeth Gould, the wife of James Buller (1717–1765), MP.[1]

The Bullers were an old Cornish family, long seated at Morval in Cornwall until their removal to Downes. The family estates, including Downes, inherited in 1874 by Redvers Buller from his unmarried elder brother James Howard Buller (1835–1874)[2] included 1,191 hectares (2,942 acres) of Devon and 880 hectares (2,174 acres) of Cornwall, which in 1876 produced an income of £14,137 a year.[3]

Early career

After education at Eton, he purchased a commission in the 60th Rifles in May 1858.[4] He served in the Second Opium War and was promoted captain before taking part in the Canadian Red River Expedition of 1870. In 1873–74, he was the intelligence officer under Lord Wolseley during the Ashanti campaign, during which he was slightly wounded at the Battle of Ordabai. He was promoted to major and appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath.

Zulu War and Victoria Cross

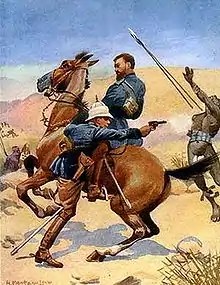

He then served in South Africa during the 9th Cape Frontier War in 1878 and the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. In the Zulu War he commanded the mounted infantry of the northern British column under Sir Evelyn Wood. He fought at the British defeat at the Battle of Hlobane, where he was awarded the Victoria Cross for bravery under fire. The following day he fought in the British victory at the Battle of Kambula. After the Zulu attacks on the British position were beaten off, he led a ruthless pursuit by the mounted troops of the fleeing Zulus. In June 1879, he again commanded mounted troops at the Battle of Ulundi, a decisive British victory which effectively ended the war.

His VC citation reads:

For his gallant conduct at the retreat at Inhlobana, on the 28th March, 1879, in having assisted, whilst hotly pursued by Zulus, in rescuing Captain C. D'Arcy, of the Frontier Light Horse, who was retiring on foot, and carrying him on his horse until he overtook the rear guard. Also for having on the same date and under the same circumstances, conveyed Lieutenant C. Everitt, of the Frontier Light Horse, whose horse had been killed under him, to a place of safely. Later on, Colonel Buller, in the same manner, saved a trooper of the Frontier Light Horse, whose horse was completely exhausted, and who otherwise would have been killed by the Zulus, who were within 80 yards of him.[5]

In an interview to The Register newspaper of Adelaide, South Australia, dated 2 June 1917, Trooper George Ashby of the Frontier Light Horse (also referred to as "Pulleine's Pets") attached to the 24th Regiment gave an account of his rescue by Col. Buller:

... it was discovered that the mountain was surrounded by a vast horde of Zulus. An attempt was made to descend on the side opposite to the pass. Cpl. Ashby and his little party endeavoured to fight their way down, and at last he and a man named Andrew Gemmell, now living in New Zealand, were the only ones left. With their faces to the foe, firing as they retired, they kept the Zulus at bay. Then an unfortunate thing happened, Cpl. Ashby's rifle burst, but, fortunately for him, Col. Buller, afterwards Sir Redvers Buller, who was one of the party, came galloping by, and offered to take him up behind him. Col. Buller was a heavy man, and his horse was a light one, and realizing this, Cpl. Ashby declined his generous offer. But the Colonel stayed with him, and, Cpl. Ashby having picked up a rifle and ammunition from a fallen comrade, the two men retired, firing whenever a foeman showed himself. They eventually reached the main camp, and for this service, as well as for saving the lives of two fellow-officers on the same occasion, Col. Buller received the Victoria Cross. Out of 500 men who made the attack on the Zjilobane Mountain, more than 300 met their death."[6]

First Boer War, Sudan and Ireland

In the First Boer War of 1881 he was Sir Evelyn Wood's chief of staff and the following year was again head of intelligence, this time in the Egypt campaign, and was knighted.

He had married Audrey, the daughter of the 4th Marquess Townshend, in 1882 and in the same year was sent to the Sudan in command of an infantry brigade and fought at the battles of El Teb and Tamai, and the expedition to relieve General Gordon in 1885. He was promoted to major-general. He was sent to Ireland in 1886, to head an inquiry into moonlighting by police personnel. He returned to the Army as Quartermaster-General to the Forces the following year and in 1890 promoted to Adjutant-General to the Forces, becoming a Lieutenant general on 1 April 1891.[7] He was appointed Honorary Colonel of the 1st (Exeter and South Devon) Volunteer Battalion, Devonshire Regiment, on 4 May 1892.[8] Although expected to be made Commander-in-Chief of the British Army by Lord Rosebery's government on the retirement of the Duke of Cambridge in 1895, this did not happen because the government was replaced and Lord Wolseley was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Army instead. On 24 June 1896 Buller was promoted to full General.[9]

Second Boer War and sacking

Buller became head of the troops stationed at Aldershot in 1898. He was sent as commander of the Natal Field Force in 1899 on the outbreak of the Second Boer War. On seeing the list of troops which would make up his Corps Buller is said to have remarked "well, if I can't win with these, I ought to be kicked." By early September 1899 he had serious thoughts that the Boers could not easily be browbeaten, and that White's forces in Natal might receive some punishment if they deployed too far forward. He arrived at the end of October.[10] He was defeated at the Battle of Colenso, during what was later to become known as Black Week. Defeats at the Battle of Magersfontein and Battle of Stormberg also involved forces under his command. Because of concerns about his performance and negative reports from the field he was replaced in January 1900 as overall commander in South Africa by Lord Roberts. Defeats and questionable ability as commander soon earned him the nickname "Reverse Buller" among troops. He remained as second-in-command and suffered two more setbacks in his attempts to relieve Ladysmith at the battles of Spion Kop and Vaal Krantz. On his fourth attempt, Buller was victorious in the Battle of the Tugela Heights, lifting the siege on 28 February 1900, the day after Piet Cronje at last surrendered to Roberts at Paardeberg.[11] After Roberts took Bloemfontein (13 March 1900), Buller correctly predicted that the Boers would take to guerrilla warfare.[12] Later he was successful in flanking Boer armies out of positions at Biggarsberg, Laing's Nek and Lydenburg. It was Buller's veterans who won the Battle of Bergendal in the war's last set-piece action.

Buller was also popular as a military leader amongst the public in England, and he had a triumphal return from South Africa with many public celebrations, including those on 10 November 1900 when he went to Aldershot to resume his role as General Officer Commanding Aldershot District,[13] later to be remembered as "a Buller day". He spent the following months giving lectures and speeches on the war, was promoted to a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (GCMG) in Nov 1900,[14] and received the Honorary Freedom of the Borough of Plymouth in April 1901.[15] However, his reputation had been damaged by his early reverses in South Africa, especially within the Unionist government. When public disquiet emerged over the continuing guerrilla activities by the defeated Boers, the Minister for War, St. John Brodrick and Lord Roberts sought a scapegoat.[16] The opportunity was provided by the numerous attacks in the newspapers on the performance of the British Army. The matter came to a head when a virulent piece written by The Times journalist Leo Amery was publicly answered by Buller in a speech on 10 October 1901. Brodrick and Roberts saw their opportunity to pounce and, summoning Buller to an interview on 17 October, Brodrick, with Roberts in support, demanded his resignation on the grounds of breaching military discipline. Buller refused and was summarily dismissed on half pay on 22 October.[17] His request for a court martial was refused, as was his request to appeal to the King.

Later life

There were many public expressions of sympathy for Buller, especially in the West Country, where in 1905 by public subscription a notable statue by Adrian Jones of Buller astride his war horse was erected in Exeter on the road from his home town of Crediton (facing away from Crediton to the annoyance of its inhabitants).

He received the Honorary Freedom of the borough of Blandford on 1 December 1902.[19]

Buller described himself as a Whig and a Liberal Unionist, but declined a number of offers, from both sides, to stand for Parliament at the 1906 election.[20] Buller continued his quiet retirement, until on 29 May 1907 he accepted the post of Principal Warden of the Goldsmiths' Company which he held until his death in 1908.

Marriage and offspring

In 1882, aged 43, he married Lady Audrey Jane Charlotte Townshend (d. 1926), widow of Greville Howard (son of Charles Howard, 17th Earl of Suffolk) by whom she had issue, and daughter of John Townshend, 4th Marquess Townshend by his wife Elizabeth Jane Crichton-Stuart, daughter of Lord George Stuart, younger son of John Crichton-Stuart, 1st Marquess of Bute. By his wife he had issue an only child and daughter:[21]

- (Audrey Charlotte) Georgiana Buller (1884–1953), awarded the Royal Red Cross (R.R.C.) and a Dame Commander, Order of the British Empire (1920), of Bellair House, Exeter. She served as an administrator of the War Hospitals in Exeter during World War I[2] and died unmarried in 1953.

Death, burial and succession

Buller died on 2 June 1908, at the family seat, Downes House, Crediton, Devon, and is buried in the churchyard of Holy Cross Church in Crediton. The entire western side of the chancel arch inside the church forms an elaborate monument to Sir Redvers.

As he died without male progeny he was succeeded in the family estates by his next surviving younger brother Arthur Tremayne Buller (born 1850), his father's fifth son.[2]

Legacy

Historian Richard Holmes (1946–2011) commented that Buller has gone down as "one of the bad jokes of Victorian military history", and quotes a famous verdict that he was "an admirable captain, an adequate major, a barely satisfactory colonel and a disastrous general". Viscount Esher called him "a gallant fellow but no strategist".[22] Wolseley praised his "stern determination of character". At least one recent historian has been kinder to his reputation:

Buller's achievements have been obscured by his mistakes. In 1909, a French military critic, General Langlois, pointed out that it was Buller, not Roberts, who had the toughest job of the war – and it was Buller who was the innovator in countering Boer tactics. The proper use of cover, of infantry advancing in rushes, co-ordinated in turn with creeping barrages of artillery: these were the tactics of truly modern war, first evolved by Buller in Natal.

Place name tributes

England

In England the Royal Corps of Transport barracks at Aldershot is named after him, as is a road in North Camp between Farnborough and Aldershot, and Buller Court in Farnborough (built upon the site of Buller House). Two adjacent roads in Tottenham, London, namely Redvers Road and Buller Road (adjacent to Mafeking Road), bear his name, as do a road in Brighton, Redvers Buller Road in Chesterfield, Derbyshire (adjacent to Baden Powell Road and Lord Roberts Road (after Lord Roberts of Kandahar)), Buller Street in Derby, Buller Road in Croydon and Buller Street and Mews in Bury, Lancashire (yards from the old Lancashire Fusiliers Wellington Barracks on Bolton Road). Chatham also has a Redvers Road and a Buller Road next to each other, opposite a Natal Road, and adjacent to roads and avenues named after some other Boer War Generals: Haig, Kitchener, Symons and White. Leicester also has a Buller Road adjacent to other streets named after Anglo Boer War Generals. Brighton also has a Redvers and a Buller Road, along with other references to the war: Mafeking Road, Ladysmith Road and Kimberley Road nearby. Buller Road in Exeter is close to Redvers Road, crossed by Nelson Road. Exeter School has a Buller House.

Canada

In British Columbia Buller Street in Ladysmith is named after him, near Roberts Street and Kitchener Street. The town of Redvers, in Saskatchewan, is named after him. In Ontario, Buller Street in Woodstock is named after him.

Trinidad and Tobago

Buller Street in Port of Spain is one of seven streets bearing the names of officers of the British Army who distinguished themselves during the Second Boer War: Roberts, Kitchener, Baden-Powell, Buller, Methuen, MacDonald and William Forbes Gatacre.

Monuments

His Victoria Cross is displayed at the Royal Green Jackets (Rifles) Museum in Winchester, England.

Winchester Cathedral

There is a memorial to Buller, in the form of his recumbent effigy, in the north transept of Winchester Cathedral, England.[24] The inscription reads, "A great leader – Beloved of his men."[25]

Exeter

A bronze equestrian statue of Buller by Adrian Jones (1905)[18] is situated in Exeter at the junction of New North Road and Hele Road, on the route between the city and Buller's home at Downes, Crediton, and since 1970[26][27] it has stood outside Exeter College. In January 2021, Exeter City Council voted to move the statue away from the college on the grounds that its connection to "British imperialism" meant it was "inappropriate" to be "outside an educational establishment which includes young people from diverse backgrounds".[28][29] In February 2021, the council abandoned plans to move the statue, though temporary information boards will be installed and the council will consider removing the words "He saved Natal" from the plinth.[30][31]

Crediton

The entire western side of the chancel arch inside Holy Cross Church in Crediton forms an elaborate monument to Buller, designed by William Douglas Caröe with sculpture of St George by Nathaniel Hitch (1845–1938).[32][33] A brass mural tablet was erected in Crediton Church by his only daughter Georgiana Buller. The Wetherspoons public house in Crediton bears his name.[34]

Citations

- Pirie-Gordon 1937, p. 279.

- Pirie-Gordon 1937, p. 278.

- Bateman 1883, p. 66.

- "No. 22142". The London Gazette. 21 May 1858. p. 2518.

- "No. 24734". The London Gazette. 17 June 1879. p. 3966.

- "A ROMANTIC CAREER". The Register. Vol. LXXXII, no. 22, 017. Adelaide. 2 June 1917. p. 6 – via National Library of Australia.

- "No. 26152". The London Gazette. 14 April 1891. p. 2061.

- Army List.

- "No. 26759". The London Gazette. 17 July 1896. p. 4095.

- Holmes 2004, p. 56.

- Holmes 2004, p. 97.

- Holmes 2004, p. 101.

- Beckett 2008.

- "No. 27306". The London Gazette. 19 April 1901. p. 2698.

- "General Buller at Plymouth". The Times. No. 36427. 12 April 1901. p. 8.

- Powell 1994, p. 199.

- "Sir Redvers Buller relieved of his command". The Times. No. 36593. London. 23 October 1901. p. 3.

- Pevsner & Cherry 2004, p. 436.

- "Court Circular". The Times. No. 36940. London. 2 December 1902. p. 10.

- Powell 1994, p. 203.

- Mural tablet erected by Georgiana Buller. Crediton Church.

- Holmes 2004, p. 39

- Pakenham 1979, p. 485.

- "War Memorials Online". Warmemorialsonline.org.uk. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- "Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel Redvers Henry Buller CB page Page 3 of 3". King's Royal Rifle Corps Association. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- "Exeter Memories - Exeter College". Exetermemories.co.uk.

- "University of Exeter". Exeter.ac.uk.

- "Council votes to remove statue to Victoria Cross-winning general over 'British imperialism' links". The Daily Telegraph. 12 January 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- "Councillors vote to apply for Exeter statue relocation after review". BBC News. 13 January 2021.

- "Army general statue in Exeter: Council drops relocation plan". BBC News. 10 February 2021.

- Malvern, Jack. "General Sir Redvers Buller sees off his foes in Exeter statue battle". The Times.

- "The Buller Memorial". Crediton Parish Church. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- Winbolt 1929.

- Adams, John (8 December 2003). "JD Wetherspoon Pubs". ucl.ac.uk.

General and cited references

- Bateman, John (1883). The Great Landowners of Great Britain and Ireland. Harrison and Sons.

- Beckett, Ian F. W. (January 2008) [2004]. "Buller, Sir Redvers Henry (1839–1908)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32165. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Holmes, Richard (2004). The Little Field Marshal: A Life of Sir John French. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-84614-0.

- Pakenham, Thomas (1979). The Boer War. Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-42742-3.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Cherry, Bridget (2004). The Buildings of England: Devon. London. p. 436.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Pirie-Gordon, Charles Harry Clinton (1937). Burke's Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry. Shaw cum Burke.

- Powell, Geoffrey (1994). Buller: A Scapegoat? A Life of General Sir Redvers Buller VC. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-4738-1287-1.

- Symons, Julian (1963). Buller's Campaign. Cresset Press.

- Winbolt, Samuel Edward (1929). Devon. Bell's pocket guides., English counties. London: G. Bell & Sons.

Further reading

- Dixon, Norman F. (1994). On the Psychology of Military Incompetence. Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-5889-8.

- Harvey, David (1999). Monuments to courage: Victoria Cross headstones and memorials. Kevin and Kay Patience.

External links

- Location of grave and VC medal (Devonshire)

- General Sir Redvers Buller Statue in Exeter Archived 13 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Crediton Parish Church article