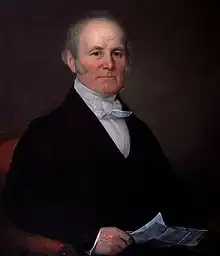

Samuel Cunard

Sir Samuel Cunard, 1st Baronet (21 November 1787 – 28 April 1865), was a British-Canadian shipping magnate, born in Halifax, Nova Scotia, who founded the Cunard Line, establishing the first scheduled steamship connection with North America.[1] He was the son of a master carpenter and timber merchant who had fled the American Revolution and settled in Halifax.[2]

Samuel Cunard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 21 November 1787 |

| Died | 28 April 1865 (aged 77) Kensington, London, England |

| Occupation | Shipping magnate |

Family and early life

Samuel Cunard was the second son of Abraham Cunard (1756–1824), a Quaker and Margaret Murphy (1758-1821),[3] a Roman Catholic. The Cunards were a Quaker family that originally came from Worcestershire, in Britain, but were forced to flee to Germany in the 17th century due to religious persecution, where they took the name Kunder. Samuel Cunard's great-great-grandfather had been a dyer in Crefeld there, but emigrated to Pennsylvania in 1683. In America they adopted the name Cunard. Later some of his descendants, including his grandfather, Samuel, changed their name to Cunard. Abraham Cunard was a Loyalist to the British Crown and moved to Halifax in 1783, after the American Revolution. He married Margaret Murphy, another Loyalist émigrée that year. Margaret's family were originally from Ireland and came to Halifax from South Carolina.[4][5] Abraham and Margaret had nine children, two girls and seven boys (William 1789–1823, Samuel 1787–1865, Edward 1798–1851, Joseph 1799–1865, John, Thomas and Henry).[6]

Abraham Cunard was a master carpenter who worked for the British garrison in Halifax and became a wealthy landowner and timber merchant.[6] Samuel Cunard's own business skills were evident early in his teens: he was managing his own general store from stock he obtained in broken lots at wharf auction. He later joined his father in the family timber business, which expanded into investments in shipping.[3]

Adulthood and career

During the War of 1812, Cunard volunteered for service in the 2nd Battalion of the Halifax Regiment militia and rose to the rank of captain. He held many public offices, such as volunteer fireman and lighthouse commissioner, and maintained a reputation as not only a shrewd businessman, but also an honest and generous citizen.[3]

Cunard was a highly successful entrepreneur in Halifax shipping and one of a group of twelve individuals who dominated the affairs of Nova Scotia. He secured mail packet contracts and provided a fisheries patrol vessel for the province. Cunard diversified his family's timber and shipping business with investments in whaling, tea imports and coal mining, as well as the Halifax Banking Company and the Shubenacadie Canal. The whaling ships, sent far into the Southern Atlantic, seldom if ever turned a profit.[3] He purchased large amounts of land in Prince Edward Island, at one point owning a seventh of the province, which involved him in the protracted disputes between tenants on the island and the absentee landlords who owned most of it.[7][3]

Steamships

Cunard experimented with steam, cautiously at first, becoming a founding director of the Halifax Steamboat Company, which built the first steamship in Nova Scotia in 1830, the long-serving and successful SS Sir Charles Ogle for the Halifax–Dartmouth Ferry Service.[3] The first steam boat had already been built by Aaron Manby in 1822.[1] Cunard became president of the company in 1836 and arranged for steam power for their second ferry, Boxer in 1838.[8] Cunard led Halifax investors to combine with Quebec business in 1831 to build the pioneering ocean steamship Royal William to run between Quebec and Halifax. Although Royal William ran into problems after losing an entire season due to cholera quarantines, Cunard learned valuable lessons about steamship operation. He commissioned a coastal steamship named Pochohontas in 1832 for mail service to Prince Edward Island and later purchased a larger steamship Cape Breton to expand the service.[9]

Cunard's experience in steamship operation, with observations of the growing railway network in England, encouraged him to explore the creation of a Transatlantic fleet of steamships, which would cross the ocean as regularly as trains crossed land. He went to the United Kingdom seeking investors in 1837. He set up a company with several other businessmen to bid for the rights to run a transatlantic mail service between the UK and North America. It was successful in its bid, the company later becoming Cunard Steamships Limited.

In 1840 the company's first steamship, the Britannia, sailed from Liverpool to Halifax, Nova Scotia, and on to Boston, Massachusetts, with Cunard and 63 other passengers on board, marking the beginning of regular passenger and cargo service. Establishing a long unblemished reputation for speed and safety, Cunard's company made ocean liners a success, in the face of many potential rivals who lost ships and fortunes. Cunard's ships proved successful, but their high costs saddled Cunard with heavy debts by 1842, and he had to flee to England from creditors in Halifax. However, by 1843, Cunard ships were earning enough to pay off his debts and begin issuing modest but growing dividends. Cunard divided his time between Nova Scotia and England but increasingly left his Nova Scotian operations in the hands of his sons Edward and William, as business drew him to spend more time in London.[10]

Cunard made a special trip to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in 1850, when his brother Joseph Cunard's timber and shipping businesses in New Brunswick collapsed in a bankruptcy that threw as many as 1000 people out of work. Cunard took out loans and personally guaranteed all of his brother's debts in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Boston. Joseph Cunard moved to Liverpool, England where Samuel helped him re-establish his shipping interests.

Views on segregation

Cunard throughout his personal life was not a religious man and was considered by many to be agnostic. His views on slavery in the 19th century were not known, but his statements regarding Frederick Douglass's segregated passage arranged by a Cunard Agent in Liverpool on one of his ocean liners in 1845 strongly suggests he was against any form of racial prejudice. "No one can regret more than I do the unpleasant circumstances surrounding Mr. Douglass's passage from Liverpool, but I can assure you that nothing of the kind will again take place on the steamships in which I am connected." His views on race reflected those of Britons of the time, who regarded mistreatment of black people as a moral wrong, even though they still considered them to be socially and intellectually inferior to white people.

Later life

Cunard owned a number of companies in Canada. After his death and changes to the British mail contract, his partners in England dropped his Canadian service and it would be 50 years before his ships returned to Canada.[11] His coal company in Nova Scotia, which he bought to fuel his liners, remained the family's major investment in Nova Scotia and continued into the 20th century as Cunard Fuels, later bought out by the Irving Family of New Brunswick.

In 1859 Cunard was made a baronet by Queen Victoria.[12]

Sir Samuel Cunard died at Kensington in London on 28 April 1865. He is buried at Brompton Cemetery in London.[11] He lies against the eastern wall.

Legacy

At the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, a substantial portion of the second floor is dedicated to his life, the Cunard Line and its famous ships.[13] A large bronze statue of Samuel Cunard was erected in October 2006 on the Halifax waterfront, beside the Ocean Terminal Wharves long used by Cunard's liners.[14] A stamp of Cunard's likeness was issued by Canada Post in 2004.[3]

Despite challenges from competing companies and changes in technology, the prosperous company grew, eventually absorbed many others such as the Canadian Northern Steamships Limited, and in 1934 its principal competition, the White Star Line, owners of the successful RMS Olympic and former owners of the ill-fated Titanic. After that, Cunard dominated the Atlantic passenger trade with some of the world's most famous liners such as the RMS Queen Mary[15] and RMS Queen Elizabeth.[16] His name lives on today in the Cunard Line, now a prestigious branch of the Carnival Line cruise empire.[17]

Family

Samuel Cunard was married to Susan, daughter of William Duffus, on 4 February 1815 (she died 28 February 1828 - see photo), by whom he had nine children,[18] two sons (Edward 1816–1869 and William 1825–1906) and seven daughters (Mary 1817–1885,[lower-alpha 1] Susan 1819–, Margaret Ann 1820–1901, Sarah Jane 1821–1902,[lower-alpha 2] Ann Elizabeth 1823–1862,[lower-alpha 3] Isabella 1827–1894[lower-alpha 4] and Elizabeth 1828–1889.[6]

Sir Samuel Cunard was succeeded in both the business and the baronetcy by his oldest son, Sir Edward Cunard, 2nd baronet, who married Mary Bache McEvers (daughter of Bache McEvers), and through whom the baronetcy was passed down. Their son, Bache Edward Cunard, 3rd baronet married the society hostess Emerald, Lady Cunard (1872–1948). They in turn had one daughter, Nancy Cunard (1896–1965), writer, heiress and political activist.

William Cunard, second son of Sir Samuel Cunard, married Laura Charlotte Haliburton, daughter of author and politician Thomas Chandler Haliburton. The couple had three sons and one daughter.[19] William built the Halifax School for the Deaf. Samuel Cunard's daughter Margaret married William Leigh Mellish (1813–1864), soldier, landowner and cricketer.

Notes

- Mary m. James Horsfield Peters

- Sarah Jane m. Gilbert William Francklyn, parents of Charles G. Francklyn

- Ann Elizabeth m. Ralph Shuttleworth Allen

- Isabella m. Henry Holden

References

- "United Kingdom – ERIH". www.erih.net. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- "Sir Samuel Cunard". Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- Langley 2006

- Lownds 1987, p. 3.

- Smy 1997.

- Blakeley, Phyllis R. (1976). "Cunard, Sir Samuel". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IX (1861–1870) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Boileau p. 94

- Boileau, p. 40

- Boileau, pp. 49–50

- Boileau, pp. 75–76

- Boileau, p. 96

- "No. 22235". The London Gazette. 1 March 1859. p. 953.

- "Mauretania/Lusitania Model Refit Completed", Cunard Steamship Society, Dec. 17, 2011

- Richard H. Wagner, "Sir Samuel and the New Queen Victoria", Beyond Ships, originally published in The Porthole, The World Ship Society, January 2007)

- "Queen Mary". Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- "Queen Elizabeth (1939)". Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- "WLCL Homepage". Retrieved 25 December 2008.

- "Mellish, Lt.–Col. Henry". Who's Who: 1093. 1919.

- Morgan, Henry James, ed. (1903). Types of Canadian Women and of Women who are or have been Connected with Canada. Toronto: Williams Briggs. p. 68.

Bibliography

- Langley, John G. (2006). Steam Lion: A biography of Samuel Cunard. Halifax, NS: Nimbus Publishing Ltd.

- Lownds, Russ, ed. (1987). Samuel Cunard Bicentennial 1787–1987. Halifax: Samuel Cunard Bicentennial Committee.

- Smy, William Arthur (Fall 1997). "Loyalist Cunards". Loyalist Gazette. 35 (2).

- Transatlantic by Stephan Fox

- John Boileau, Samuel Cunard: Nova Scotia's Master of the North Atlantic Halifax: Formac (2006)

- Sir Samuel Cunard Biography at Chris' Cunard Page