William Kingston

Sir William Kingston, KG (c. 1476 – 14 September 1540) was an English courtier, soldier and administrator. He was the Constable of the Tower of London during much of the reign of Henry VIII. Among the notable prisoners he was responsible for were Queen Anne Boleyn, as well as the men accused of adultery with her. He was MP for Gloucestershire in 1529 and 1539.[1]

Sir William Kingston | |

|---|---|

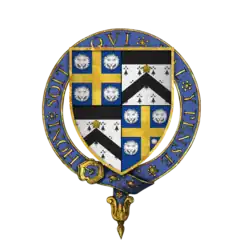

Arms of Sir William Kingston, KG | |

| Born | c. 1476 |

| Died | 14 September 1540 Painswick, Gloucestershire |

| Spouse(s) | Anne Berkeley Elizabeth (surname unknown) Mary Scrope |

| Issue | Sir Anthony Kingston Bridget Kingston |

Life

He was of a Gloucestershire family, settled at Painswick. William appears to have been a yeoman of the guard before June 1509. In 1512 he was an under-marshal in the army; went to the Spanish coast; was with Dr. William Knight in October of that year at San Sebastián, and discussed with him the course to be pursued with the disheartened English forces who had come to Spain under Thomas Grey, 2nd Marquess of Dorset. He fought at the battle of Flodden, was knighted in 1513, became sewer to the king, and later (1521) was a carver. He was appointed High Sheriff of Gloucestershire for 1514–15.

He seems to have been with Sir Richard Wingfield, the ambassador, at the French court early in 1520, for Wingfield wrote to Henry VIII (20 April) that the Dauphin took a shine to him. Kingston took part in the tilting at the Field of the Cloth of Gold, and was at the meeting with the Emperor Charles V in July. Henry seems to have liked him, and presented him with a valuable horse. For the next year or two, he was a diligent country magistrate and courtier, levying men for the king's service in the west, and living when in London with the Black Friars.

In April 1523 Kingston joined Dacre on the disturbed northern frontier, and with Sir Ralph Ellerker had the most dangerous posts assigned him; he was present at the capture of Cessford Castle, the stronghold of the Kers, on 18 May. He returned rather suddenly to London, and was made knight of the king's body and captain of the guard. On 30 August 1523 he landed at Calais in the army of Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk. Surrey wrote from the north lamenting his absence. On 28 May 1524, he became constable of the Tower at a salary of £100. He signed the petition to Pope Clement VII for the hastening of the king's divorce, on 13 July 1530.

In November 1530 Kingston went down to Sheffield Park, home of the Earl of Shrewsbury,[2] to take charge of Thomas Wolsey. The cardinal is said to have been alarmed at his coming because it had been foretold that he should meet his death at Kingston. Kingston tried to reassure him, and was with him at the time of his death, riding to London to acquaint the king with the circumstances. On 11 October 1532 he landed at Calais with Henry on the way to the second interview with Francis I of France at Boulogne, and on 29 May 1533 he took an official part in the coronation of Anne Boleyn.

He was elected MP for Gloucestershire in 1529 and 1539.

He seems to have become prematurely aged, but continued to be constable. He received Anne Boleyn on 2 May 1536, when committed a prisoner to the Tower, and with his wife, Mary, took charge of her and reported her conversations to Thomas Cromwell. To him, Anne made sardonic jokes. The information he passed on to the King helped seal the fate of the Queen and the five men accused with her.[3] Kingston's dispatches are today held as being one of the most important pieces of proof that Anne was entirely innocent, as were those who died with her.

Kingston was made controller of the household on 9 March 1539, and knight of the Garter on 24 April following. He had many small grants, and on the dissolution of monasteries received the site of the Flaxley Abbey, Gloucestershire.

He died at Painswick, Gloucestershire, on 14 September 1540. He was buried in the chantry chapel in a tomb of Purbeck marble. There were formerly monumental brasses to him and his wife, Elizabeth.[4]

Marriages and issue

Kingston's first two marriages were to a wife named Elizabeth whose surname is unknown, and to Anne (née Berkeley), the widow of Sir John Gyse or Guise (d. 30 September 1501), and daughter of Sir William Berkeley (d. 1501) of Weoley (in Northfield), Worcestershire, by Anne Stafford, daughter of Sir Humphrey Stafford of Grafton, Worcestershire, slain by Jack Cade 7 June 1450.[5][6] By his first two wives Kingston had a son and daughter:[7]

- Bridget Kingston, who married Sir George Baynham (d. 6 May 1546) of Clearwell, Gloucestershire, son and heir of Sir Christopher Baynham (d. 6 October 1557).[8] After the death of Bridget (née Kingston), George Baynham married Cecilia Gage, the daughter of Sir John Gage (1479–1556) of Firle.[9]

- Sir Anthony Kingston, who married firstly, before October 1524, Dorothy Harpur, the daughter of Robert Harpur, and secondly, by 1537, Mary Gainsford, widow of Sir William Courtenay (d. 1535) of Powderham, and daughter of Sir John Gainsford of Crowhurst, Surrey. He had no issue by either marriage, but by a mistress had two illegitimate sons, Anthony and Edmund.[10]

He married thirdly, Mary (née Scrope) (d. 25 August 1548), the widow of Edward Jerningham (d. 6 January 1515), and one of the nine daughters of Richard Scrope (d. 1485) of Upsall, Yorkshire, second son of Henry Scrope, 4th Baron Scrope of Bolton (4 June 1418 – 14 January 1459). She was the sister of Elizabeth Scrope (d. 1537), who married firstly William Beaumont, 2nd Viscount Beaumont, and secondly, John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford, and of Margaret Scrope (d. 1515), who married Edmund de la Pole, 3rd Duke of Suffolk.[11][12][13][14][15] Kingston had no issue by his third marriage.

Notes

- "KINGSTON, Sir William (by 1476-1540), of the Blackfriars, London and Elmore and Painswick, Glos. - History of Parliament Online". Historyofparliamentonline.org. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- "Cardinal Wolsey's Visit". Archived from the original on 20 January 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- p. 374, Eric Ives, Anne Boleyn

- Davis 1899, pp. 216–17.

- Richardson I 2011, pp. 117–19.

- Richardson II 2011, pp. 37–8, 378.

- Lehmberg 2004.

- Maclean 1881, pp. 149–51.

- Questier 2006, p. 524.

- Loades 2004.

- Norcliffe 1881, pp. 279–80.

- Cokayne 1949, p. 543.

- Cokayne 1945, p. 243.

- Raine 1865, pp. 297–8.

- A Who’s Who of Tudor Women: Sa-Sn Archived 21 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine, compiled by Kathy Lynn Emerson to update and correct Wives and Daughters: The Women of Sixteenth-Century England (1984) Retrieved 26 May 2013.

References

- Cokayne, George Edward (1945). The Complete Peerage, edited by H.A. Doubleday. Vol. X. London: St. Catherine Press. pp. 239–244.

- Cokayne, George Edward (1949). The Complete Peerage, edited by Geoffrey H. White. Vol. XI. London: St. Catherine Press. pp. 543–4.

- Davis, Cecil T. (1899). The Monumental Brasses of Gloucestershire. London: Phillimore & Co. pp. 216–17. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- Lehmberg, Stanford (2004). "Kingston, Sir William (c. 1476–1540)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15628. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Loades, David (2004). "Kingston, Sir Anthony (c. 1508–1556)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15626. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Maclean, John, ed. (1881). "The History of the Manors of Dene Magna and Abenhall". Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. Bristol: C.T. Jefferies. VI: 123–209. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- Norcliffe, Charles Best, ed. (1881). The Visitation of Yorkshire in the Years 1563 and 1564 made by William Flower. Vol. XVI. London: Harleian Society. pp. 279–80. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- Questier, Michael C. (2006). Catholicism and Community in Early Modern England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 524.

- Raine, James, ed. (1865). Testamenta Eboracensia. Vol. III. London: Surtees Society. pp. 297–99. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Vol. I (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 978-1449966379.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Vol. II (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 978-1449966386.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Archbold, William Arthur Jobson (1892). "Kingston, William (d.1540)". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 31. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 186–187.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Archbold, William Arthur Jobson (1892). "Kingston, William (d.1540)". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 31. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 186–187.