Sitti Nurbaya

Sitti Nurbaya: Kasih Tak Sampai (Sitti Nurbaya: Unrealized Love, often abbreviated Sitti Nurbaya or Siti Nurbaya; original spelling Sitti Noerbaja) is an Indonesian novel by Marah Rusli. It was published by Balai Pustaka, the state-owned publisher and literary bureau of the Dutch East Indies, in 1922. The author was influenced by the cultures of the west Sumatran Minangkabau and the Dutch colonials, who had controlled Indonesia in various forms since the 17th century. Another influence may have been a negative experience within the author's family; after he had chosen a Sundanese woman to be his wife, Rusli's family brought him back to Padang and forced him to marry a Minangkabau woman chosen for him.

Cover of the 44th printing | |

| Author | Marah Rusli |

|---|---|

| Original title | Sitti Nurbaya: Kasih Tak Sampai |

| Country | Indonesia |

| Language | Indonesian |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | Balai Pustaka |

Publication date | 1922 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 291 (45th printing) |

| ISBN | 978-979-407-167-0 (45th printing) |

| OCLC | 436312085 |

Sitti Nurbaya tells the story of two teenage lovers, Samsul bahri and Sitti Nurbaya, who wish to be together but are separated after Samsul bahri is forced to go to Batavia. Not long afterwards, Nurbaya unhappily offers herself to marry the abusive and rich Datuk Meringgih as a way for her father to escape debt; she is later killed by Meringgih. It ends with Samsulbahri, now a member of the Dutch colonial army, killing Datuk Meringgih during an uprising and then dying from his wounds.

Written in formal Malay and including traditional Minangkabau storytelling techniques such as pantuns, Sitti Nurbaya touches on the themes of colonialism, forced marriage, and modernity. Well-received upon publication, Sitti Nurbaya continues to be taught in Indonesian high schools. It has been compared to Romeo and Juliet and the Butterfly Lovers.

Writing

Sitti Nurbaya was written by Marah Rusli, a Dutch-educated Minangkabau from a noble background with a degree in veterinary science.[1] His Dutch education led him to become Europeanized. He abandoned some Minangkabau traditions, but not his view of the subordinate role of women in society. According to Bakri Siregar, an Indonesian socialist literary critic, Rusli's Europeanisation affected how he described Dutch culture in Sitti Nurbaya, as well a scene where the two protagonists kiss.[2] A. Teeuw, a Dutch critic of Indonesian literature and lecturer at the University of Indonesia, notes that the use of pantuns (a Malay poetic form) shows that Rusli was heavily influenced by Minangkabau oral literary tradition, while the extended dialogues show influence from the tradition of musyawarah (in-depth discussions by a community to reach an agreement).[3]

Indonesian critic Zuber Usman credits another, more personal, experience as influencing Rusli in writing Sitti Nurbaya and his positive view of European culture and modernity. After expressing interest in choosing a Sundanese woman to become his wife, which "caused an uproar among his family", Rusli was told by his parents to return to his hometown and marry a Minangkabau woman chosen by them; this caused conflict between Rusli and his family.[4]

Plot

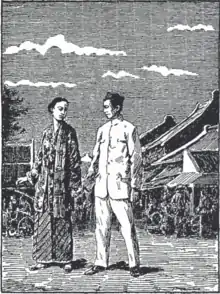

In Padang in the early 20th century Dutch East Indies, Samsulbahri and Sitti Nurbaya–children of rich noblemen Sutan Mahmud Syah and Baginda Sulaiman–are teenage neighbours, classmates, and childhood friends. They begin to fall in love, but they are only able to admit it after Samsu tells Nurbaya that he will be going to Batavia (Jakarta) to study. After spending the afternoon at a nearby hillside, Samsu and Nurbaya kiss on her front porch. When they are caught by Nurbaya's father and the neighbours, Samsu is chased out of Padang and goes to Batavia.

Meanwhile, Datuk Meringgih, jealous of Sulaiman's wealth and worried about the business competition, plans to bankrupt him. Meringgih's men destroy Sulaiman's holdings, driving him to bankruptcy and forcing him to borrow money from Meringgih. When Meringgih tries to collect, Nurbaya offers to become his wife if he will forgive her father's debt; Datuk Meringgih accepts.

Writing to Samsu, Nurbaya tells him that they can never be together. However, after surviving Meringgih's increasingly violent outbursts, she runs away to Batavia to be with Samsu. They fall in love again. Upon receiving a letter regarding her father's death, Nurbaya hurries back to Padang, where she dies after unwittingly eating a lemang rice cake poisoned by Meringgih's men on his orders. Receiving news of her death by letter, Samsu seemingly commits suicide.[5]

Ten years later, Meringgih leads an uprising against the Dutch colonial government to protest a recent tax increase. During the uprising, Samsu (now a soldier for the Dutch) meets Meringgih and kills him, but is mortally wounded himself. After meeting with his father and asking for forgiveness, he dies and is buried next to Nurbaya.

Characters

- Sitti Nurbaya

- Sitti Nurbaya (sometimes spelled Siti Nurbaya; abbreviated Nurbaya) is the title character and one of the main protagonists. Indonesian short-story writer and literary critic Muhammad Balfas describes her as a character who is capable of making her own decisions, indicated by her decision to marry Datuk Meringgih when he threatens her father, willingness to take control with Samsulbahri, and dismissal of Datuk Meringgih after the death of her father. She is also independent enough to move to Batavia to look for Samsulbahri on her own. Her actions are seen as being heavily against adat—the strong Indonesian cultural norms—and this eventually leads to her being poisoned.[6] Her beauty, to the point that she is called "the flower of Padang", is seen as a physical manifestation of her moral and kind nature.[7]

- Samsulbahri

- Samsulbahri (sometimes spelled Sjamsulbahri; abbreviated Samsu) is the primary male protagonist. He is described as having skin the colour of langsat, with eyes as black as ink; however, from afar he can be confused with a Dutchman. These physical attributes have been described by Keith Foulcher, a lecturer of Indonesian language and literature at the University of Sydney, as indicating Samsu's mimicry and collaborationist nature.[8] His good looks are also seen as a physical manifestation of his moral and kind nature.[7]

- Datuk Meringgih

- Datuk Meringgih is the primary antagonist of the story. He is a trader who originated from a poor family, and became rich as a result of shady business dealings. Indonesian writer and literary critic M. Balfas described Meringgih's main motivations as greed and jealousy, being unable to "tolerate that there should be anyone wealthier than he".[9] Balfas writes that Datuk Meringgih is a character that is "drawn in black and white, but strong enough to create serious conflicts around him."[6] He later becomes the "champion of anti-colonist resistance", fuelled only by his own greed; Foulcher argues that it is unlikely that Datuk Meringgih's actions were an attempt by Rusli to insert anti-Dutch commentary.[10]

Style

According to Bakri Siregar, the diction in Sitti Nurbaya does not reflect Marah Rusli's personal style, but a "Balai Pustaka style" of formal Malay, as required by the state-owned publisher. As a result, Rusli's orally-influenced story telling technique, often wandering from the plot to describe something "at the whim of the author",[lower-alpha 1] comes across as "lacking".[lower-alpha 2][11]

Sitti Nurbaya includes pantuns (Malay poetic forms) and "clichéd descriptions",[12] although not as many as contemporary Minangkabau works.[13] The pantuns are used by Nurbaya and Samsul in expressing their feelings for each other,[3] such as the pantun

Padang Panjang dilingkari bukit, |

Padang Panjang is surrounded by hills, |

Its main messages are presented through debates between characters with a moral dichotomy, to show alternatives to the author's position and "thereby present a reasoned case for [its] validation". However, the "correct" (author's) point of view is indicated by the social and moral standing of the character presenting the argument.[15]

Themes

Sitti Nurbaya is generally seen as having an anti-forced marriage theme or illustrating the conflict between Eastern and Western values.[9] It has also been described as "a monument to the struggle of forward-thinking youth" against Minangkabau adat.[1]

However, Balfas writes that it is unjust to consider Sitti Nurbaya as only another forced marriage story, as the marriage of Nurbaya and Samsu would have been accepted by society.[6] He instead writes that Sitti Nurbaya contrasts Western and traditional views of marriage, criticising the traditionally accepted dowry and polygamy.[12]

Reception

Rusli's family was not pleased with the novel; his father condemned him in a letter, as a result of which Rusli never returned to Padang.[4] His later novel, Anak dan Kemenakan (1958) was even more critical of older generation's inflexibility.[16]

Until at least 1930, Sitti Nurbaya was one of Balai Pustaka's most popular works, often being borrowed from lending libraries. After Indonesia's independence, Sitti Nurbaya was taught as a classic of Indonesian literature; this has led to it being "read more often in brief synopsis than as an original text by generation after generation of Indonesian high school students".[1] As of 2008, it has seen 44 printings.[17]

Sitti Nurbaya is generally considered one of the most important works of Indonesian literature,[18] with its love story being compared to William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet and the Chinese legend of the Butterfly Lovers.[19] Some Western critics, including Dutch critic A. Teeuw and writer A. H. Johns, consider it to be the first true Indonesian novel, as opposed to Azab dan Sengsara,[20] which was less developed in its theme of forced marriage and the negative aspects of adat.[18]

Teeuw wrote that the moral messages and sentimentality in Sitti Nurbaya are overdone, similar to Azab dan Sengsara. However, he considers the plot of Sitti Nurbaya more interesting for a reader from a Western background than the older novel.[3]

Siregar wrote that Rusli "in many things acts as a dalang",[lower-alpha 3] or puppet master, occasionally removing the characters in order to speak directly to the reader, making the message too one-sided. He considered the plot to be forced in places, as if the author were preventing the story from flowing naturally.[13] He considered Rusli a mouthpiece of the Dutch colonial government, who had controlled Indonesia since the early 17th century, for making Samsul, "the most sympathetic character",[lower-alpha 4] a member of the Dutch forces and Datuk Meringgih, "the most antipathetic character",[lower-alpha 5] the leader of Indonesian revolutionary forces, as well as for Rusli's antipathy to Islam in the novel.[21]

Sitti Nurbaya inspired numerous authors, including Nur Sutan Iskandar, who stated that he wrote Apa Dayaku Karena Aku Perempuan (What Am I to Do Because I Am a Girl, 1924) as a direct result of reading it; Iskandar later wrote Cinta yang Membawa Maut (Love that Brings Death, 1926), which deals with the same themes. The Sitti Nurbaya storyline has often been reused, to the point that Balfas has referred to similar plots as following "the 'Sitti Nurbaya' formula".[12]

Adaptations

Sitti Nurbaya has been translated into numerous languages, including Malaysian in 1963.[18] It has been adapted into a sinetron (soap opera) twice. The first, in 1991, was directed by Dedi Setiadi, and starred Novia Kolopaking in the leading role, Gusti Randa as Samsulbahri, and HIM Damsyik as Datuk Meringgih.[22][23] The second, starting in December 2004, was produced by MD Entertainment and broadcast on Trans TV. Directed by Encep Masduki and starring Nia Ramadhani as the title character, Ser Yozha Reza as Samsulbahri, and Anwar Fuady as Datuk Meringgih, the series introduced a new character as a competitor for Samsul's affections.[19]

In 2009, Sitti Nurbaya was one of eight classics of Indonesian literature chosen by Taufik Ismail to be reprinted in a special Indonesian Cultural Heritage Series edition; Sitti Nurbaya featured a West Sumatran-style woven cloth cover.[24][25] Actress Happy Salma was chosen as its celebrity icon.[26]

In 2011, Sitti Nurbaya was translated into English by George A Fowler[27] and published by the Lontar Foundation.[28]

Notes

Explanatory notes

- Original: "... menurut kesenangan dan selera hati [penulis] ..."

- Original: "... kurang baik ..."

- Original: "Dalam banjak hal penulis bertindak sebagai dalang ... "

- Original: "... Samsulbahri, tokoh jang paling simpatetik ... "

- Original: "... Datuk Meringgih, tokoh jang paling antipatik ... "

References

Footnotes

- Foulcher 2002, pp. 88–89.

- Siregar 1964, pp. 43–44.

- Teeuw 1980, p. 87.

- Foulcher 2002, p. 101.

- Kaya, Indonesia. "Warisan Sastra Indonesia Dalam Lantunan Lagu Dan Tarian Di Drama Musikal 'Siti Nurbaya (Kasih Tak Sampai)' | Liputan Budaya - Situs Budaya Indonesia". IndonesiaKaya (in Indonesian). Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- Balfas 1976, p. 54.

- Foulcher 2002, p. 91.

- Foulcher 2002, p. 90.

- Balfas 1976, p. 53.

- Foulcher 2002, p. 98.

- Siregar 1964, pp. 51–52.

- Balfas 1976, p. 55.

- Siregar 1964, p. 52.

- Rusli 2008, p. 48.

- Foulcher 2002, pp. 96–97.

- Mahayana, Sofyan & Dian 2007, p. 131.

- Rusli 2008, p. iv.

- Mahayana, Sofyan & Dian 2007, p. 8.

- KapanLagi 2004, broadcast.

- Balfas 1976, p. 52.

- Siregar 1964, p. 48.

- Eneste 2001, p. 48.

- KapanLagi 2004, auditions.

- Febrina 2009.

- Veda 2009.

- Jakarta Post 2009, Happy Salma.

- Rusli, Marah (31 July 2011). Sitti Nurbaya. BookCyclone.

- "Sitti Nurbaya | lontar". Retrieved 4 January 2022.

Bibliography

- Balfas, Muhammad (1976). "Modern Indonesian Literature in Brief". In Brakel, L. F. (ed.). Handbuch der Orientalistik [Handbook of Orientalistics]. Vol. 1. Leiden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-04331-2. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- Eneste, Pamusuk (2001). Bibliografi Sastra Indonesia [Bibliography of Indonesian Literature] (in Indonesian). Magelang, Indonesia: Yayasan Indonesiatera. ISBN 978-979-9375-17-9. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- Foulcher, Keith (2002). "Dissolving into the Elsewhere: Mimicry and ambivalence in Marah Roesli's 'Sitti Noerbaja'". In Foulcher, Keith; Day, Tony (eds.). Clearing a Space: Postcolonial Readings of Modern Indonesian Literature. Leiden: KITLV Press. pp. 85–108. ISBN 978-90-6718-189-1. OCLC 51857766. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- Mahayana, Maman S.; Sofyan, Oyon; Dian, Achmad (2007). Ringkasan dan Ulasan Novel Indonesia Modern [Summaries and Commentary on Modern Indonesian Novels] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Grasindo. ISBN 978-979-025-006-2. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- Rusli, Marah (2008) [1922]. Sitti Nurbaya: Kasih Tak Sampai [Sitti Nurbaya: Unrealized Love]. Jakarta: Balai Pustaka. ISBN 978-979-407-167-0. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- Siregar, Bakri (1964). Sedjarah Sastera Indonesia [History of Indonesian Literature]. Vol. 1. Jakarta: Akademi Sastera dan Bahasa "Multatuli". OCLC 63841626.

- Teeuw, A. (1980). Sastra Baru Indonesia [New Indonesian Literature] (in Indonesian). Vol. 1. Ende: Nusa Indah. OCLC 222168801.

Online sources

- Febrina, Anissa S. (31 August 2009). "Revitalizing the Classics". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- "Happy Salma encourages literacy". The Jakarta Post. 15 June 2009. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- "Sitti Nurbaya Versi Baru akan di Tayangkan di Trans TV" [The New Version of Sitti Nurbaya will be Broadcast on Trans TV]. KapanLagi.com (in Indonesian). 2004. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- "Trans TV Audisi untuk 'Siti Nurbaya'" [Trans TV Auditions for 'Siti Nurbaya']. KapanLagi.com (in Indonesian). 2004. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- Veda, Titania (12 June 2009). "Reviving a Nation's Literary Heritage". Jakarta Globe. Archived from the original on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2011.