Superabsorbent polymer

A superabsorbent polymer (SAP) (also called slush powder) is a water-absorbing hydrophilic homopolymers or copolymers[1] that can absorb and retain extremely large amounts of a liquid relative to its own mass.[2]

Water-absorbing polymers, which are classified as hydrogels when mixed,[3] absorb aqueous solutions through hydrogen bonding with water molecules. A SAP's ability to absorb water depends on the ionic concentration of the aqueous solution. In deionized and distilled water, a SAP may absorb 300 times its weight[4] (from 30 to 60 times its own volume) and can become up to 99.9% liquid, and when put into a 0.9% saline solution the absorbency drops to approximately 50 times its weight. The presence of valence cations in the solution impedes the polymer's ability to bond with the water molecule.

The SAP's total absorbency and swelling capacity are controlled by the type and degree of cross-linkers used to make the gel. Low-density cross-linked SAPs generally have a higher absorbent capacity and swell to a larger degree. These types of SAPs also have a softer and stickier gel formation. High cross-link density polymers exhibit lower absorbent capacity and swell, and the gel strength is firmer and can maintain particle shape even under modest pressure.

Superabsorbent polymers are crosslinked in order to avoid dissolution. There are three main classes of SAPs:

1. Cross‐linked polyacrylates and polyacrylamides

2. Cellulose‐ or starch‐acrylonitrile graft copolymers

3. Cross‐linked maleic anhydride copolymers[1]

The largest use of SAPs is found in personal disposable hygiene products, such as baby diapers, adult diapers and sanitary napkins.[5] SAPs were discontinued from use in tampons due to 1980s concern over a link with toxic shock syndrome. SAPs are also used for blocking water penetration in underground power or communications cable, in self-healing concrete,[6][7] horticultural water retention agents, control of spill and waste aqueous fluid, and artificial snow for motion picture and stage production. The first commercial use was in 1978 for use in feminine napkins in Japan and disposable bed liners for nursing home patients in the USA. Early applications in the US market were with small regional diaper manufacturers as well as Kimberly Clark.[8]

Superabsorbent polymer: Polymer that can absorb and retain extremely large amounts of a liquid relative to its own mass.[9] Notes:

- The liquid absorbed can be water or an organic liquid.

- The swelling ratio of a superabsorbent polymer can reach the order of 1000:1.

- Superabsorbent polymers for water are frequently polyelectrolytes.

History

Until the 1920s, water absorbing materials were fiber-based products. Choices were tissue paper, cotton, sponge, and fluff pulp. The water absorbent capacity of these types of materials is only up to 11 times their weight and most of it is lost under moderate pressure.

In the early 1960s, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) was conducting work on materials to improve water conservation in soils. They developed a resin based on the grafting of acrylonitrile polymer onto the backbone of starch molecules (i.e. starch-grafting). The hydrolyzed product of the hydrolysis of this starch-acrylonitrile co-polymer gave water absorption greater than 400 times its weight. Also, the gel did not release liquid water the way that fiber-based absorbents do.

The polymer came to be known as “Super Slurper”.[10] The USDA gave the technical know-how to several USA companies for further development of the basic technology. A wide range of grafting combinations were attempted including work with acrylic acid, acrylamide and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA).

Today's research has proved the ability of natural materials, e.g. polysaccharides and proteins, to perform super absorbent properties in pure water and saline solution (0.9%wt.) within the same range as synthetic polyacrylates do in current applications.[11] Soy protein/poly(acrylic acid) superabsorbent polymers with good mechanical strength have been prepared.[12] Polyacrylate/polyacrylamide copolymers were originally designed for use in conditions with high electrolyte/mineral content and a need for long term stability including numerous wet/dry cycles. Uses include agricultural and horticultural. With the added strength of the acrylamide monomer, used as medical spill control, wire and cable water blocking.

Copolymer chemistry

Superabsorbent polymers are now commonly made from the polymerization of acrylic acid blended with sodium hydroxide in the presence of an initiator to form a poly-acrylic acid sodium salt (sometimes referred to as sodium polyacrylate). This polymer is the most common type of SAP made in the world today. According to U.S Food & Drug Administration, sodium polyacrylate is listed in Food Additive Status List, and there are strict limitations.[13]

Other materials are also used to make a superabsorbent polymer, such as polyacrylamide copolymer, ethylene maleic anhydride copolymer, cross-linked carboxymethylcellulose, polyvinyl alcohol copolymers, cross-linked polyethylene oxide, and starch grafted copolymer of polyacrylonitrile to name a few. The latter is one of the oldest SAP forms created.

Today superabsorbent polymers are made using one of three primary methods: gel polymerization, suspension polymerization or solution polymerization. Each of the processes have their respective advantages but all yield a consistent quality of product.

Gel polymerization

A mixture of acrylic acid, water, cross-linking agents and UV initiator chemicals are blended and placed either on a moving belt or in large tubs. The liquid mixture then goes into a "reactor" which is a long chamber with a series of strong UV lights. The UV radiation drives the polymerization and cross-linking reactions. The resulting "logs" are sticky gels containing 60-70% water. The logs are shredded or ground and placed in various sorts of driers. Additional cross-linking agent may be sprayed on the particles' surface; this "surface cross-linking" increases the product's ability to swell under pressure—a property measured as Absorbency Under Load (AUL) or Absorbency Against Pressure (AAP). The dried polymer particles are then screened for proper particle size distribution and packaging. The gel polymerization (GP) method is currently the most popular method for making the sodium polyacrylate superabsorbent polymers now used in baby diapers and other disposable hygienic articles.

Solution polymerization

Solution polymers offer the absorbency of a granular polymer supplied in solution form. Solutions can be diluted with water prior to application, and can coat or saturate most substrates. After drying at a specific temperature for a specific time, the result is a coated substrate with superabsorbency. For example, this chemistry can be applied directly onto wires and cables, though it is especially optimized for use on components such as rolled goods or sheeted substrates.

Solution-based polymerization is commonly used today for SAP manufacture of co-polymers, particularly those with the toxic acrylamide monomer. This process is efficient and generally has a lower capital cost base. The solution process uses a water-based monomer solution to produce a mass of reactant polymerized gel. The polymerization's own exothermic reaction energy is used to drive much of the process, helping reduce manufacturing cost. The reactant polymer gel is then chopped, dried and ground to its final granule size. Any treatments to enhance performance characteristics of the SAP are usually accomplished after the final granule size is created.

Suspension polymerization

The suspension process is practiced by only a few companies because it requires a higher degree of production control and product engineering during the polymerization step. This process suspends the water-based reactant in a hydrocarbon-based solvent. The net result is that the suspension polymerization creates the primary polymer particle in the reactor rather than mechanically in post-reaction stages. Performance enhancements can also be made during, or just after, the reaction stage.

Aviation

On 13 April 2010, Cathay Pacific flight 780 from Surabaya to Hong Kong encountered a dual engine stall descending whilst descending into Hong Kong International Airport, the aircraft landed safely with no fatalities. The investigation concluded that superabsorbent polymer (SAP) spheres, a component of a fuel filter monitor installed in a fueling dispenser at Juanda International Airport caused the main metering valves in the fuel metering unit to seize. It was discovered that salt water had contaminated the fuel supply at Juanda International Airport after, which led to damage of the filter monitors and release of SAP spheres into the aircraft's fuel, eventually entering the main fuel supply lines.[14]

Uses

- Artificial snow for motion picture and stage productions

- Candles

- Cement-based materials (e.g. concrete)[15]

- Composites and laminates

- Controlled release of insecticides and herbicides

- Diapers and adult diapers

- Drown-free water source for feeder insects

- Expandable water toys

- Expansion microscopy

- Filtration applications

- Fire-retardant gel

- Flood control

- Fragrance carrier

- Frog tape (high tech masking tape designed for use with latex paint)

- Fuel monitoring systems in aviation and vehicles

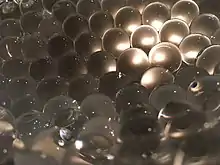

- Gel blasters (a cross between paintball and airsoft; used in China)[16]

- Hot and cold therapy packs

- Magical effects

- Medical waste solidification

- Motionless water beds

- Potting soil

- Spill control

- Surgical pads

- Waste stabilization and environmental remediation

- Water absorbent pads

- Water gel

- Water retention for supplying water to plants

- Wire and cable water blocking

- Wound dressings[17]

- Food additives[18][19]

Citations

- Hawaii Energy and Environmental Technologies (HEET) Initiative. July 2016.

- Horie, K, et al., 890.

- Kabiri, K. (2003). "Synthesis of fast-swelling superabsorbent hydrogels: effect of crosslinker type and concentration on porosity and absorption rate". European Polymer Journal. 39 (7): 1341–1348. doi:10.1016/S0014-3057(02)00391-9.

- Mignon, Arn; Vermeulen, Jolien; Snoeck, Didier; Dubruel, Peter; Van Vlierberghe, Sandra; De Belie, Nele (2017-10-28). "Mechanical and self-healing properties of cementitious materials with pH-responsive semi-synthetic superabsorbent polymers". Materials and Structures. 50 (6): 238. doi:10.1617/s11527-017-1109-4. ISSN 1871-6873. S2CID 255318116.

- Sun, Fang; Messner, Bernfried A. (December 5, 2006), Manufacture of web superabsorbent polymer and fiber, archived from the original on August 29, 2011

- Snoeck, Didier; Van Tittelboom, Kim; Steuperaert, Stijn; Dubruel, Peter; De Belie, Nele (2012-03-15). "Self-healing cementitious materials by the combination of microfibres and superabsorbent polymers". Journal of Intelligent Material Systems and Structures. 25: 13–24. doi:10.1177/1045389X12438623. hdl:1854/LU-6869809. S2CID 92983639.

- Mignon, Arn; Devisscher, Dries; Graulus, Geert-Jan; Stubbe, Birgit; Martins, José; Dubruel, Peter; De Belie, Nele; Van Vlierberghe, Sandra (2017-01-02). "Combinatory approach of methacrylated alginate and acid monomers for concrete applications". Carbohydrate Polymers. 155: 448–455. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.08.102. hdl:1942/22766. ISSN 0144-8617. PMID 27702534. S2CID 46760339.

- Mulder, Douglas C.; O'Ryan, David E. (December 31, 1985), Method and apparatus for powder coating a moving web: US 4561380 A

- Horie, K.; Barón, Máximo; Fox, R. B.; He, J.; Hess, M.; Kahovec, J.; Kitayama, T.; Kubisa, P.; Maréchal, E.; Mormann, W.; Stepto, R. F. T.; Tabak, D.; Vohlídal, J.; Wilks, E. S.; Work, W. J. (1 January 2004). "Definitions of terms relating to reactions of polymers and to functional polymeric materials (IUPAC Recommendations 2003)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 76 (4): 889–906. doi:10.1351/pac200476040889. S2CID 98351038.

- "SUPER SLURPER Compound with a super thirst". Agricultural Research: 7–9. June 1975.

- Zohuriaan-Mehr, M.J (2009). "Protein- and homo poly(amino acid)-based hydrogels with super-swelling properties". Polymers for Advanced Technologies. 20 (8): 655–671. doi:10.1002/pat.1395.

- Song, W., Xin, J., Zhang J. (2017). "One-pot synthesis of soy protein (SP)-poly (acrylic acid) (PAA) superabsorbent hydrogels via facile preparation of SP macromonomer". Industrial Crops and Products. 100: 117–125. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.02.018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Polymer Substances and Polymer Adjuvants for Food Treatment - 173.73 Sodium polyacrylate". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- Report on the accident to Airbus A330-342 B-HLL operated by Cathay Pacific Airways Limited at Hong Kong International Airport, Hong Kong on 13 April 2010 (PDF) (Report). Civil Aviation Department The Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. July 2013. Retrieved 10 Oct 2023.

- Jensen, Ole Mejlhede (2013). "Use of superabsorbent polymers in concrete" (PDF). Concrete International. 35 (1): 48–52.

- "水弹枪_百度图片搜索".

- Da Silva Jr., Macedo Carlos (January 31, 2008), ADHESIVE BANDAGE: United States Patent Application 20080027366

- "Food Additive Status List". U.S. Food & Drug Administration.

- "Safety of sodium polyacrylate, potassium polyacrylate". Socopolymer.

References

- K. Horie; M. Báron; R. B. Fox; J. He; M. Hess; J. Kahovec; T. Kitayama; P. Kubisa; E. Maréchal; W. Mormann; R. F. T. Stepto; D. Tabak; J. Vohlídal; E. S. Wilks & W. J. Work (2004). "Definitions of terms relating to reactions of polymers and to functional polymeric materials (IUPAC Recommendations 2003)" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 76 (4): 889–906. doi:10.1351/pac200476040889. S2CID 98351038.

- Katime Trabanca, Daniel; Katime Trabanca, Oscar; Katime Amashta, Issa Antonio (September 2004). Los materiales inteligentes de este milenio: Los hidrogeles macromoleculares. Síntesis, propiedades y aplicaciones (1 ed.). Bilbao: Servicio Editorial de la Universidad del País Vasco (UPV/EHU). ISBN 978-84-8373-637-1.

- Buchholz, Fredric L; Graham, Andrew T, eds. (1997). Modern Superabsorbent Polymer Technology (1 ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-19411-8.