Smederevo

Smederevo (Serbian Cyrillic: Смедерево, pronounced [smêdereʋo] ⓘ) is a city and the administrative center of the Podunavlje District in eastern Serbia. It is situated on the right bank of the Danube, about 45 kilometres (28 miles) downstream of the Serbian capital, Belgrade.

Smederevo

| |

|---|---|

| City of Smederevo | |

From top: Republic Square, Church of Saint George, Courthouse in Smederevo, Town hall, Gymnasium in Smederevo, Smederevo Fortress, Obrenović Villa | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

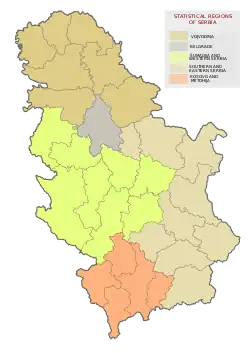

Location of the city of Smederevo within Serbia | |

| Coordinates: 44°40′N 20°56′E | |

| Country | Serbia |

| District | Podunavlje |

| Settlements | 28 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jovan Beč (SNS) |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 42.03 km2 (16.23 sq mi) |

| • Administrative | 484.30 km2 (186.99 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 72 m (236 ft) |

| Population (2022 census)[1] | |

| • Rank | 13th in Serbia |

| • Urban | 59,261 |

| • Urban density | 1,400/km2 (3,700/sq mi) |

| • Administrative | 97,930 |

| • Administrative density | 200/km2 (520/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code |

|

| Area code | +381(0)26 |

| Car plates | SD |

| Website | www |

According to the 2022 census, the city has a population of 59,261, with 97,930 people living in its administrative area.

Its history starts in the 1st century BC, after the conquest of the Roman Empire, when there existed a settlement by the name of Vinceia. The modern city traces its roots back to the Late Middle Ages when it was the capital (1430–39, and 1444–59) of the last independent Serbian state before Ottoman conquest.

Smederevo is said to be the city of iron (Serbian: гвожђе / gvožđe) and grapes (грожђе / grožđe).

Names

In Serbian, the city is known as Smederevo (Смедерево), in Latin, Italian, Romanian and Greek as Semendria, in Hungarian as Szendrő or Vég-Szendrő, in Turkish as Semendire.

The name of Smederevo was first recorded in the Charter of the Byzantine Emperor Basil II from 1019, in the part related to the Eparchy of Braničevo (a suffragan diocese of the Archdiocese of Ochrid. Another written record is found in the Charter of Duke Lazar of Serbia from 1381, by which he bestowed the Monastery of Ravanica and villages and properties 'to the Great Bogosav with the commune and heritage'’.

The Latin-Italian name also occurs in Belogradum et Semendria and Belgrado e Semendria, two of the short-lived 20th-century synonyms of the Latin titular bishopric of Belgrade, which was suppressed in 1948 in favor of the residential Latin Archdiocese of Belgrade (Beograd) and 'newly' established titular bishopric of Alba Marittima.

Coat of arms

Smederevo Coat of Arms uses two shades of blue, which deviates from the heraldic principles (only one shade of every color, contrasting those). Also, the bar with the year 1430 is placed over the shield. Emblem elements are six white discs arranged 3 + 2 + 1, which represents grapes, Smederevo Fortress, dark blue and white horizontal lines (representing the Danube).

History

Early

In the 7th millennium BC, the Starčevo culture existed for millennia, succeeded by the 6th millennium BC Vinča culture that prospered in the region. The Paleo-Balkan tribes of Dacians and Thracians emerged in the area in the 2nd millennia BC, with the Celtic Scordisci raiding the Balkans in the 3rd century B.C.

The Roman Empire conquered Vinceia in the 1st century BC. It was organized into Moesia, later Moesia Superior,[2] and in the administrative reforms of Diocletian (244–311) it was part of the Diocese of Moesia, then the Diocese of Dacia. It was a principal town of Moesia Superior, near the confluence of Margus and Brongus rivers.[3][4]

Middle Ages

The modern founder of the city was the Serbian Despot Đurađ Branković in the 15th century, who built Smederevo Fortress in 1430 as the new Serbian capital.[5] Smederevo was the residence of the Branković house and the capital of the Serbian Despotate from 1430 until 1439, when it was conquered by the Ottoman Empire after a siege lasting two months.

Sanjak of Smederevo

In 1444, in accordance with the terms of the Peace of Szeged between the Kingdom of Hungary and the Ottoman Empire the Sultan returned Smederevo to Đurađ Branković, who was allied to John Hunyadi.[6] On 22 August 1444 the Serb prince peacefully took possession of the evacuated town.[7] When Hunyadi broke the peace treaty, Đurađ Branković remained neutral. Serbia became a battleground between the Kingdom of Hungary and the Ottomans, and the angry Branković captured Hunyadi after his defeat at the Second Battle of Kosovo in 1448. Hunyadi was imprisoned in Smederevo fortress for a short time.

In 1454 Sultan Mehmed II besieged Smederevo and devastated Serbia. The town was liberated by Hunyadi. In 1459 Smederevo was again captured by the Ottomans after the death of Branković. The town became a Turkish border-fortress, and played an important part in Ottoman–Hungarian Wars until 1526. Due to its strategic location, Smederevo was gradually rebuilt and enlarged. For a long period, the town was the capital of the Sanjak of Smederevo.

In autumn 1476, a joint army of Hungarians and Serbs tried to capture the fortress from the Ottomans. They built three wooden counter-fortresses, but after months of siege, Sultan Mehmed II himself came to drive them away. After fierce fighting the Hungarians agreed to withdraw. In 1494 Pál Kinizsi tried to capture Smederevo from the Ottomans.[8] In 1512 John Zápolya unsuccessfully laid siege to the town.[6]

Modern

During the First Serbian Uprising in 1806, the city became the temporary capital of Serbia, as well as the seat of the Praviteljstvujušči sovjet, a government headed by Dositej Obradović. The first basic school was founded in 1806. During World War II, the city was occupied by German forces, who stored ammunition in the fortress. On 5 June 1941, a catastrophic explosion severely damaged the fortress, killing nearly 2,000 residents.

After World War II, Smederevo became an industrial and cultural center of Podunavlje District. Under the overall industrial development of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, the city received a boost in infrastructure. Due to the ideal geographical position of Smederevo, socialist government supported building of roads, apartment buildings and tens of factories.

Some of the most notable factories built and renewed in period between 1950s until the end of 1980s were Zelvoz (Heroj Srba during the period of SFRJ), renewed in 1966. and a new steel plant built on outskirts of Smederevo at that time, Sartid (MKS during the period of SFRJ) which was completely operational in 1971.

Settlements

Aside the city of Smederevo, the administrative area includes the following 27 settlements (number of population according to 2022 census in brackets[1]):

- Badljevica (315)

- Binovac (357)

- Dobri Do (810)

- Drugovac (1,302)

- Kolari (1,014)

- Kulič (229)

- Landol (1,210)

- Lipe (2,727)

- Lugavčina (2,516)

- Lunjevac (428)

- Mala Krsna (1,550)

- Malo Orašje (816)

- Mihajlovac (2,248)

- Osipaonica (2,873)

- Petrijevo (1,363)

- Radinac (4,714)

- Ralja (1,114)

- Šalinac (501)

- Saraorci (1,704)

- Seone (880)

- Skobalj (1,397)

- Suvodol (690)

- Udovice (1,764)

- Vodanj (1,085)

- Vranovo (2,456)

- Vrbovac (855)

- Vučak (1,751)

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 59,545 | — |

| 1953 | 66,132 | +2.12% |

| 1961 | 77,682 | +2.03% |

| 1971 | 90,650 | +1.56% |

| 1981 | 107,366 | +1.71% |

| 1991 | 115,617 | +0.74% |

| 2002 | 109,809 | −0.47% |

| 2011 | 108,209 | −0.16% |

| 2022 | 97,930 | −0.90% |

| Source: [9] | ||

Ethnic groups

The ethnic composition of the municipality:[10]

| Ethnic group | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| Serbs | 89,054 | 90,94% |

| Roma | 2,317 | 2,37% |

| Macedonians | 183 | |

| Yugoslavs | 144 | |

| Croats | 99 | |

| Montenegrins | 99 | |

| Hungarians | 62 | |

| Albanians | 46 | |

| Romanians | 40 | |

| Russians | 38 | |

| Muslims | 27 | |

| Bulgarians | 22 | |

| Slovaks | 20 | |

| Germans | 15 | |

| Vlachs | 14 | |

| Ukrainians | 13 | |

| Slovenes | 11 | |

| Bosniaks | 8 | |

| Bunjevci | 1 | |

| Others | 131 | |

| Regional affiliation | 17 | |

| Did not declare | 879 | |

| Unknown | 4,690 | |

| Total | 97,930 |

Economy

Smederevo has a recent history of heavy industry and manufacturing, which is a result of intense industrialization of the region during the 1950s-1960s era. Previously, this entire geographical region had a heavy focus on agricultural production.

The city is home to the only operating steel mill in the country - Železara Smederevo, previously known as Sartid, which is situated in the suburb of Radinac. This was privatized and sold to U.S. Steel in 2003 for $33 million.[11] Following the global economic crisis, U.S. Steel sold the plant to the government of Serbia for a symbolic $1 to avoid closing the plant. The plant was renamed Železara Smederevo and at the time employed 5,400 workers.[12] In 2016, the Serbian government managed to strike a deal with a Chinese conglomerate Hesteel Group, which purchased the effective assets for $46 million.[13]

The "Milan Blagojević" home appliance factory is the second largest industry company in the city. Smederevo is also an agricultural area, with significant production of fruit and vines. However, the large agricultural combine "Godomin" has been in financial difficulty since the 1990s and is almost defunct as of 2005. The grape variety known as Smederevka is named after the city. The "Ishrana" factory is an important supplier of bakery products in northern and eastern Serbia.

A U.S.-Dutch consortium, Comico Oil, planned to build a $250 million oil refinery in the industrial zone of the city in 2012.[14] However, the consortium lost its permit to build the refinery after it failed to meet payment deadlines for the land lease a year later.[15]

As of September 2017, Smederevo has one of 14 free economic zones established in Serbia.[16]

Transportation

The river traffic infrastructure of the city of Smederevo consists of Danube waterway, old port, marina, new port, terminal for liquid Naftna Industrija Srbije loads, as well as smaller piers (gravel pits) which are located along the bank in the industrial zone. The port is registered for international traffic and is located in the very center of the city of Smederevo.

It has reloading capacities which can realize 1.5 million freight tons a year. By 2019, the Government of Serbia invested 9.5 million euros for new railway construction built for the needs of Port of Smederevo.[17] It was also announced that starting in 2020, the Government of Serbia plans to invest 93 million euros for the construction of new Port Terminal.[17][18]

Tourism

Among the main tourist attractions in the city are the Smederevo Fortress and the Obrenović Villa.

There is an old white mulberry tree in the center of Smederevo. Called Karađorđev Dud ("Karađorđe's Mulberry"), it is estimated to be over 300 years old. Though there are no historical sources to specifically confirm that, it is believed that under this tree dizdar Muharem Guša, Ottoman commander of the fortress, handed over the keys to the city to Karađorđe on 8 November 1805, after the city was liberated during the First Serbian Uprising. In May 2018 the tree was declared a natural monument of the III category, as the first "living" monument in Smederevo. The three is supported by metallic pipes, but there is an initiative that two sculptures, shaped like a male and female hand, should be installed instead.[19]

Demographics

In the 2011 census, there was 108,209 residents in the city administrative area,[20] of which 101,908 were Serbs and 2,369 were Romani.[21]

See also

References

- AGE AND SEX, publikacije.stat.gov.rs; accessed 13 July 2023.

- p. 317. author. 1839. p. 317. Retrieved 31 August 2012 – via Internet Archive.

- William Smith (1857). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Little, Brown & Company. p. 1310.

- Aaron Arrowsmith, A grammar of ancient geography: compiled for the use of King's College School (1832), p. 108, Hansard (London)

- Bobot, Rajko; Rakić, Kosta, eds. (1985). Socialist Republic of Serbia. Jugoslovenska Revija. p. 187.

Smederevo..in medieval times the capital of the Serbian despotate, is among the oldest towns in Serbia. It was here, in 1430, that despot Djuradj Branković built a fortified palace (the so-called Little Castle or Smederevo Fortress)..Later he extended it into the Big Castle..

- Ágoston, Gábor (2021). The Last Muslim Conquest: The Ottoman Empire and Its Wars in Europe. Princeton University Press. p. 67, 145. ISBN 9780691205380.

- Fine, John V. A. (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. p. 549. ISBN 9780472082605.

- Tietze, Andreas (1985). Habsburgisch-osmanische Beziehungen (in German). Verlag. p. 8. ISBN 9783853696149.

- "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- "НАЦИОНАЛНА ПРИПАДНОСТ Подаци по општинама и градовима" (PDF). publikacije.stat.gov.rs. Republički zavod za statistiku. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- Reuters Editorial. "Serbia looks east for quick steel plant sale". Reuters. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - "Serbia buys U.S. Steel plant; Price: $1". CBSNews. 31 January 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- Insajder. "Zelezara Smederevo steel mill: China's offer accepted". Insajder.net. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- "Comico Oil Wins Permit to Build $250 Million Refinery in Serbia". Bloomberg L.P. 13 March 2012.

- "Serb City Scraps Comico Oil Refinery Project on Deadline". Bloomberg L.P. 5 February 2013.

- Mikavica, A. (3 September 2017). "Slobodne zone mamac za investitore". politika.rs (in Serbian). Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- "Mihajlović: Smederevo će biti čvorište za teretni saobraćaj". danas.rs (in Serbian). Beta. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "Predviđena ulaganja od pola milijarde evra u razvoj luka u Srbiji". b92.net (in Serbian). Tanjug. 24 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- Olivera Milošević (31 May 2018). "Karađorđev dud postao prirodno dobro" [Karađorđećs mulberry became natural monument]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 12.

- Census in the city of Smederevo, pop-stat.mashke.org; accessed 15 October 2016. (in Serbian)

- "Microsoft Word - tekst, REV.GN.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- "Ozvaničena saradnja Tangšana i Smedereva" (in Serbian). Danas. 5 June 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

Sources

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 616.

External links

- Official website

- Virtual walk through Smederevo www.360serbia.com (in Serbian)

- Visit Smederevo (Tourist Organization City of Smederevo) www.visitsmederevo (in English and Serbian)

- Smederevo's Autumn