Snake River Plain

The Snake River Plain is a geologic feature located primarily within the U.S. state of Idaho. It stretches about 400 miles (640 km) westward from northwest of the state of Wyoming to the Idaho-Oregon border. The plain is a wide, flat bow-shaped depression and covers about a quarter of Idaho. Three major volcanic buttes dot the plain east of Arco, the largest being Big Southern Butte.

Most of Idaho's major cities are in the Snake River Plain, as is much of its agricultural land.

Geology

The Snake River Plain can be divided into three sections: western, central, and eastern. The western Snake River Plain is a large tectonic graben or rift valley filled with several kilometers of lacustrine (lake) sediments; the sediments are underlain by rhyolite and basalt, and overlain by basalt. The western plain began to form around 11–12 Ma (million years ago) with the eruption of rhyolite lavas and ignimbrites. The western plain is not parallel to North American Plate motion and lies at a high angle to the central and eastern Snake River Plains. Its morphology is similar to other volcanic plateaus such as the Chilcotin Group in south-central British Columbia, Canada.

The eastern Snake River Plain traces the path of the North American Plate over the Yellowstone hotspot, now centered in Yellowstone National Park. The eastern plain is a topographic depression that cuts across Basin and Range mountain structures, more or less parallel to North American Plate motion. It is underlain almost entirely by basalt erupted from large shield volcanoes. Beneath the basalts are rhyolite lavas and ignimbrites that erupted as the lithosphere passed over the hotspot.

The central Snake River plain is similar to the eastern plain but differs by having thick sections of interbedded lacustrine (lake) and fluvial (stream) sediments, including the Hagerman fossil beds.

Island Park and Yellowstone Calderas formed as the result of enormous rhyolite ignimbrite eruptions, with single eruptions producing up to 600 cubic miles (2,500 km3) of ash. Henry's Fork Caldera, measuring 18 miles (29 km) by 23 miles (37 km), may be the largest symmetrical caldera in the world. The caldera formed when a dome of magma built up and then drained away. The center of the dome collapsed, leaving a caldera. Henry's Fork Caldera lies within the older and larger Island Park Caldera, which is 50 miles (80 km) by 65 miles (105 km). Younger volcanoes that erupted after passing over the hotspot covered the plain with young basalt lava flows in places, including Craters of the Moon National Monument.

Effects on climate

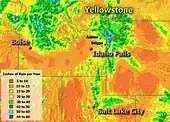

The Snake River Plain has a significant effect on the climate of Yellowstone National Park and the adjacent areas to the south and west of Yellowstone. Over time, the Yellowstone hotspot left a 70-mile (110 km) wide channel through the Rocky Mountains. This channel is in line with the gap between the Cascade Range and the Sierra Nevada. The result is a moisture channel extending from the Pacific Ocean to Yellowstone. Moisture from the Pacific Ocean streams onshore in the form of clouds and humid air. It passes through the gap between the Sierra and Cascades and into the Snake River Plain where it is channeled through most of the Rocky Mountains with no high plateaus or mountain ranges to impede its progress.[1] It finally encounters upslope conditions at the head of the Snake River Valley at Ashton, Idaho; at Island Park, Idaho; at the Teton Range east of Driggs, Idaho; and at the Yellowstone Plateau of Yellowstone National Park where the channeled moisture precipitates out as rain and snow.[2] The result is a localized climate on the eastern side of the Rockies that is akin to a climate on the west slope of the Cascades or the northern Sierra. The head of the Snake River Valley, the Tetons, and the Yellowstone Plateau receive much more precipitation than other areas of the region, and the area is known for being wet, green, having many streams, and having abundant snow in winter.

Although the topography of the Plain has largely gone unchanged for several million years, this region's climate has not been so constant. Current climatic conditions began to characterize the region in the early Pleistocene (approximately 2.5 million years ago). However, the arid climate of today was born from the gradual dissipation of a climate defined by greater moisture and narrower ranges of annual temperatures.[3][4]

References

- Bryson, R. A. and Hare, F.K. 1974 Climates of North America, Survey of Climatology, Vol. 11 Elsevier, New York p 422

- Mock, C. J., 1996 Climatic controls and spatial variations of precipitation in the western United States, Journal of Climate, 9:1111-1125

- Smith and Patterson (1994). "Mio-Pliocene seasonality on the Snake River plain: comparison of faunal and oxygen isotopic evidence" (PDF). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 107 (3–4): 291–302. Bibcode:1994PPP...107..291S. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(94)90101-5. hdl:2027.42/31761.

- Thompson, Robert (1996). "Pliocene and early Pleistocene environments and climates of the western Snake River Plain, Idaho". Marine Micropaleontology. 27 (1–4): 141–156. Bibcode:1996MarMP..27..141T. doi:10.1016/0377-8398(95)00056-9.

External links

- The Snake River Plain Archived 2012-07-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Snake River Plain at Digital Atlas of Idaho