Socotra

Socotra (/səˈkoʊtrə, soʊ-, ˈsɒkətrə/;[2] Arabic: سُقُطْرَىٰ Suquṭrā) or Saqatri (Soqotri: ساقطري Saqaṭri) is an island of the Republic of Yemen in the Indian Ocean.[3][4] Lying between the Guardafui Channel and the Arabian Sea and near major shipping routes, Socotra is the largest of the four islands in the Socotra archipelago. Since 2013, the archipelago has constituted the Socotra Governorate.

Landsat view of Socotra | |

| |

Socotra Location within Yemen  Socotra Location within the Horn of Africa near Western Asia | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Between the Guardafui Channel and the Arabian Sea |

| Coordinates | 12°30′36″N 53°55′12″E |

| Archipelago | Socotra |

| Total islands | 4 + two rocky islets[1] |

| Major islands | Socotra, Abd al Kuri, Samhah, Darsah |

| Area | 3,796 km2 (1,466 sq mi) |

| Length | 132 km (82 mi) |

| Width | 50 km (31 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,503 m (4931 ft) |

| Highest point | Mashanig, Hajhir Mountains |

| Administration | |

| Region | |

| Governorate | Socotra Archipelago |

| Districts | Hadibu (east) Qulansiyah wa 'Abd-al-Kūrī (west) |

| Capital and largest city | Hadibu (pop. 8,545) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 60,000 |

| Pop. density | 11.3/km2 (29.3/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | predominantly Soqotris; minority Yemenis, Hadharem, and Mehris |

| Official name | Socotra Archipelago |

| Type | Natural |

| Criteria | x |

| Designated | 2008 (32nd session) |

| Reference no. | 1263 |

| Region | Arab States |

The island of Socotra represents around 95% of the landmass of the Socotra archipelago. It lies 380 kilometres (205 nautical miles) south of the Arabian Peninsula[5] and 240 kilometres (130 nautical miles) east of Somalia; despite being controlled by Yemen, it is geographically part of Africa.[6] The island is isolated and home to a high number of endemic species. Up to a third of its plant life is endemic. It has been described as "the most alien-looking place on Earth."[7] The island measures 132 kilometres (82 mi) in length and 42 kilometres (26 mi) in width.[6][8] In 2008 Socotra was recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[9]

Currently, the island is under the de facto control of the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council, a secessionist participant in Yemen's ongoing civil war.[10]

Etymology

Scholars vary regarding the origin of the name of the island. The name Socotra may derive from:

- A Greek name that is derived from the name of a South Arabian tribe mentioned in Sabaic and Ḥaḑramitic inscriptions as Dhū-Śakūrid (S³krd).[11]

- The Sanskrit "Dvīpa Sukhadara" which means "island of bliss".[12]

- The Arabian terms suq, market, and qutra, a vulgar form of qatir, which refers to dragon's blood.[13]

History

There was initially an Oldowan lithic culture in Socotra. Oldowan stone tools were found in the area around Hadibo in 2008.[14]

Socotra played an important role in the ancient international trade and appears as Dioskouridou (Διοσκουρίδου νῆσος), meaning "the island of the Dioscuri" in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a first-century CE Greek navigation aid.[15]

The Hoq Cave contains a large number of inscriptions, drawings and archaeological objects. Further investigation showed that these had been left by sailors who visited the island between the first century BCE and the sixth century CE. The texts are written in the Indian Brāhmī, South Arabian, Ethiopic, Greek, Palmyrene and Bactrian languages. This corpus of nearly 250 texts and drawings constitutes one of the main sources for the investigation of Indian Ocean trade networks in that time period.[16]

In 880, an Aksumite expeditionary force conquered the island and an Oriental Orthodox bishop was consecrated. The Ethiopians were later dislodged by a large armada sent by Imam Al-Salt bin Malik of Oman.[17]

According to the Persian geographer Ibn al-Mujawir (1204–1291), who testifies having arrived in Socotra from India in 1222, there were two groups of people on the island, the indigenous mountain dwellers and the foreign coastal dwellers.[18]

In 1507, a Portuguese fleet commanded by Tristão da Cunha with Afonso de Albuquerque landed at the then capital of Suq and captured the port after a stiff battle against the Mahra Sultanate. Their objective was to set a base in a strategic place on the route to India. The lack of a proper harbor and the infertility of the land led to famine and sickness in the garrison, and the Portuguese abandoned the island in 1511.[20] The Mahra sultans took back control of the island and the inhabitants were converted to Islam.[21]

In 1834, the East India Company stationed a garrison on Socotra, in the expectation that the Mahra sultan of Qishn and Socotra would accept an offer to sell the island. The lack of good anchorages proved to be as much a problem for the British as the Portuguese. Faced with the unexpected firm refusal of the sultan to sell, the British left in 1835. After the capture of Aden by the British in 1839, they lost all interest in acquiring Socotra.

In April 1886, the British government decided to conclude a protectorate treaty with the sultan in which he promised this time to "refrain from entering into any correspondence, agreement, or treaty with any foreign nation or power, except with the knowledge and sanction of the British Government".[22]

In October 1967, in the wake of the departure of the British from Aden and southern Arabia, the Mahra Sultanate was abolished. On 30 November of the same year, Socotra became part of South Yemen.

Since Yemeni unification in 1990, it has been a part of the Republic of Yemen, affiliated first to Aden Governorate. Then in 2004, it was moved to be a part of the Hadhramaut Governorate. Later in 2013, it became a governorate of its own.

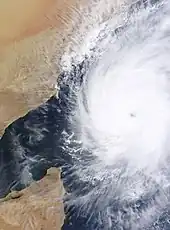

In 2015, the cyclones Chapala and Megh struck the island, causing severe damage to its infrastructure.[23]

UAE and STC control

Beginning in 2015, the UAE began increasing its presence on Socotra, first with humanitarian aid in the wake of tropical cyclones Chapala and Megh, and eventually establishing a military presence on the island.

On April 30, 2018, the UAE, as part of the ongoing Saudi Arabian–led intervention in Yemen, landed troops on the island and took control of Socotra Airport and seaport.[24] On May 14, 2018, Saudi troops were also deployed on the island and a deal was brokered between the UAE and Yemen for a joint military training exercise and the return of administrative control of the airport and seaport to Yemen.[25][26]

In May 2019, the Yemeni government accused the UAE of landing around 100 separatist troops in Socotra, which the UAE denied, deepening a rift between the two nominal allies in Yemen's civil war.[27]

In February 2020, a regiment of the Yemeni Army stationed in Socotra rebelled and pledged allegiance to the UAE-backed separatist Southern Transitional Council (STC) in Socotra, renouncing the UN-backed government of Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi.[28] The STC seized control of the island in June 2020.[29]

According to media reports in 2020 and 2022, the UAE are set to establish military and intelligence facilities on the Socotra Archipelago.[30][31]

Initially, the UAE were part of the Saudi Arabian–led intervention in Yemen launched in 2011. But this cooperation later showed cracks due to diverging geopolitical goals that led the UAE reducing its intervention forces in Yemen from 2019 onwards,[30] while increasing its support to the STC and taking over Socotra in pursuing their own geostrategic interests to retain influence across Yemen's southern coastal areas.[32] This take-over was declared illegitimate by then-Yemen president Hadi stating that the UAE was acting like an occupier.[33]

Geography

Socotra is one of the most isolated landforms on Earth of continental origin (i.e. not of volcanic origin). The archipelago was once part of the supercontinent of Gondwana and detached during the Miocene epoch, in the same set of rifting events that opened the Gulf of Aden to its northwest.[34]

Politically, the Socotra archipelago is a part of Yemen but geographically it belongs to Africa as it represents a continental fragment that is geologically linked to the continental African Somali Plate.[35]

The archipelago consists of the main island of Socotra (3,665 km2 or 1,415 sq mi), three smaller islands, Abd al Kuri, Samhah and Darsa, and two rocky islets, Ka'l Fir'awn and Sābūnīyah, both uninhabitable by humans but important for seabirds.[36]

The main island is about 125 kilometres (78 mi) long and 45 kilometres (28 mi) north to south.[37] and has three major physical regions:

- The narrow coastal plains with its characteristic dunes, formed by monsoon winds blowing during three summer months. The wind takes up the coast sand in a spiral and, as a result, forms the snow-white Socotran sand dunes.[38]

- The limestone plateaus of Momi, Homhil and Diksam with its characteristic karst topography based on limestone rock areas intersected with inter-hill plains. For centuries until recently Socotra's main economic activity was subsistent transhumant animal husbandry, predominantly goats and sheep on these plateaus. The outcome is a unique and still active cultural landscape of agro-pastoralism with its characteristic rainwater harvesting systems.[39]

- A central massif, the Hajhir Mountains, composed of granite and metamorphic rocks.[40] rising to 1,503 metres (4,931 ft).[41]

Sand dunes on the northeast coast

Sand dunes on the northeast coast Momi Plateau with rainwater harvest structures, water storage body, shelter for herders

Momi Plateau with rainwater harvest structures, water storage body, shelter for herders.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) A wadi in Socotra

A wadi in Socotra

Climate

The climate of Socotra is classified in the Köppen climate classification as BWh and BSh, meaning a transitional hot desert climate and a semi-desert climate with a mean annual temperature over 25 °C (77 °F). Yearly rainfall is light but is fairly spread throughout the year. Due to orographic lift provided by the interior mountains, especially during the northeast monsoon from October to December, the highest inland areas can average as much as 800 millimetres (31.50 in) per year and can receive over 250 millimetres (9.84 in) in a month during November and December.[42] The southwest monsoon season from June to September brings strong winds and high seas. For many centuries, the sailors of Gujarat called the maritime route near Socotra as “Sikotro Sinh”, meaning the lion of Socotra, that constantly roars—referring to the high seas near Socotra.

In an extremely unusual occurrence, the normally arid western side of Socotra received more than 410 millimetres (16.14 in) of rain from Cyclone Chapala in November 2015.[43] Cyclones rarely affect the island, but in 2015 Cyclone Megh became the strongest, and only, major cyclone to strike the island directly.

| Climate data for Socotra | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 30.0 (86.0) |

31.7 (89.1) |

32.8 (91.0) |

37.2 (99.0) |

38.5 (101.3) |

40.6 (105.1) |

37.4 (99.3) |

34.4 (93.9) |

35.6 (96.1) |

37.0 (98.6) |

33.0 (91.4) |

30.6 (87.1) |

40.6 (105.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 27.1 (80.8) |

27.8 (82.0) |

29.2 (84.6) |

31.8 (89.2) |

34.6 (94.3) |

33.8 (92.8) |

32.3 (90.1) |

32.4 (90.3) |

33.2 (91.8) |

30.8 (87.4) |

29.6 (85.3) |

28.3 (82.9) |

30.8 (87.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 24.8 (76.6) |

24.8 (76.6) |

26.3 (79.3) |

28.7 (83.7) |

31.3 (88.3) |

30.8 (87.4) |

29.5 (85.1) |

29.5 (85.1) |

29.3 (84.7) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.0 (80.6) |

25.8 (78.4) |

28.0 (82.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 22.6 (72.7) |

21.7 (71.1) |

23.3 (73.9) |

25.5 (77.9) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.9 (82.2) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.4 (79.5) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.4 (75.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

25.1 (77.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 17.0 (62.6) |

17.2 (63.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

20.3 (68.5) |

21.2 (70.2) |

22.8 (73.0) |

21.7 (71.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.2 (72.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

18.9 (66.0) |

17.0 (62.6) |

17.0 (62.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 2.5 (0.10) |

2.5 (0.10) |

10.2 (0.40) |

0.0 (0.0) |

2.5 (0.10) |

30.5 (1.20) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

2.5 (0.10) |

10.2 (0.40) |

50.8 (2.00) |

81.3 (3.20) |

193.0 (7.60) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 2.4 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 7.7 | 5.2 | 21.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 70 | 68 | 67 | 66 | 62 | 60 | 58 | 57 | 62 | 69 | 72 | 73 | 65 |

| Source: Deutscher Wetterdienst[44] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

.jpg.webp)

Socotra is considered the jewel of biodiversity in the Arabian Sea.[45] In the 1990s, a team of United Nations biologists conducted a survey of the archipelago's flora and fauna. They counted nearly 700 endemic species, found nowhere else on earth; only New Zealand,[46] Hawaii, New Caledonia, and the Galápagos Islands have more impressive numbers.[47]

The long geological isolation of the Socotra archipelago and its fierce heat and drought have combined to create a unique and spectacular endemic flora. Botanical field surveys led by the Centre for Middle Eastern Plants of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, indicate that 307 out of the 825 (37%) plant species on Socotra are endemic, i.e., they are found nowhere else on Earth.[48] The entire flora of the Socotra Archipelago has been assessed for the IUCN Red List, with three Critically Endangered and 27 Endangered plant species recognised in 2004.[48]

One of the most striking of Socotra's plants is the dragon's blood tree (Dracaena cinnabari), which is a strange-looking, umbrella-shaped tree. Its red sap was thought to be the dragon's blood of the ancients, sought after as a dye, and today used as paint and varnish.[48] Also important in ancient times were Socotra's various endemic aloes, used medicinally, and for cosmetics. Other endemic plants include the giant succulent tree Dorstenia gigas; the cucumber tree, Dendrosicyos socotranus; the rare Socotran pomegranate (Punica protopunica), Aloe perryi, and Boswellia socotrana.[49]

The island group also has a rich fauna, including several endemic species of birds, such as the Socotra starling (Onychognathus frater), the Socotra sunbird (Nectarinia balfouri), Socotra bunting (Emberiza socotrana), Socotra cisticola (Cisticola haesitatus), Socotra sparrow (Passer insularis), Socotra golden-winged grosbeak (Rhynchostruthus socotranus), and a species in a monotypic genus, the Socotra warbler (Incana incana).[49] Many of the bird species are endangered by predation by non-native feral cats.[47] With only one endemic mammal, six endemic bird species and no amphibians, reptiles constitute the most relevant Socotran vertebrate fauna with 31 species. If one excludes the two recently introduced species, Hemidactylus robustus and Hemidactylus flaviviridis, all native species are endemic. There is a very high level of endemism at both species (29 of 31, 94%) and genus levels (5 of 12, 42%). At the species level, endemicity may be even higher, as phylogenetic studies have uncovered substantial hidden diversity.[50] The reptile species include skinks, legless lizards, and one species of chameleon, Chamaeleo monachus. There are many endemic invertebrates, including several spiders (such as the Socotra Island Blue Baboon tarantula Monocentropus balfouri) and three species of freshwater crabs in the Potamidae (Socotra pseudocardisoma and two species in Socotrapotamon).[51]

As with many isolated island systems, bats are the only mammals native to Socotra. The Socotran pipistrelle (Hypsugo lanzai) is the only species of bat, and mammal in general, thought to be endemic to the island.[52][53] In contrast, the coral reefs of Socotra are diverse, with many endemic species.[49] Socotra is also one of the homes of the brush-footed butterfly Bicyclus anynana.[54]

Over the two thousand years of human settlement on the islands, the environment has slowly but continuously changed, and, according to Jonathan Kingdon, "the animals and plants that remain represent a degraded fraction of what once existed."[49] The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea states that the island had crocodiles and large lizards, and the present reptilian fauna appears to be greatly diminished since that time. Until a few centuries ago, there were rivers and wetlands on the island, greater stocks of the endemic trees, and abundant pasture. The Portuguese recorded the presence of water buffaloes in the early 17th century. Now there are sand gullies in place of rivers, and many native plants survive only where there is greater moisture or protection from roaming livestock.[49] The remaining Socotran fauna is greatly threatened by goats and other introduced species.

As a result of the 2015 Yemen civil war in mainland Yemen, Socotra became economically isolated, and fuel gas prices spiked, causing residents to turn to wood for heat. In December 2018, UAE sent cooking gas to Socotra residents to curb deforestation caused by the cutting down of trees for fuel.[55]

UNESCO recognition

The island was recognised by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as a world natural heritage site in July 2008. The European Union has supported such a move, calling on both UNESCO and the International Organisation of Protecting Environment to classify the island archipelago among the major environmental heritages.[9]

Demographics

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Most of the inhabitants are indigenous Soqotri people from Al-Mahrah tribe, who are of Southern Arabian descent from Al Mahrah Governorate,[56] and are said to be especially closely related with the Qara and Mahra groups of Southern Arabia.[57] Some of the inhabitants are African, descending from former slaves who settled on the island.[58]

Almost all inhabitants of Socotra, numbering about 50,000, live on the main island of the archipelago.[45] The principal city, Hadibu (with a population of 8,545 at the census of 2004); the second largest town, Qalansiyah (population 3,862); and Qād̨ub (population 929) are all located on the north coast of the island of Socotra.[59] Only about 450 people live on 'Abd-al-Kūrī and 100 on Samha; the island of Darsa and the islets of the archipelago are uninhabited.[60]

Language

The island is home to the Semitic language Soqotri, which is related to such other Modern South Arabian languages on the Arabian mainland as Mehri, Harsusi, Bathari, Shehri, and Hobyot, which became the subject of European academic study in the nineteenth century.[61][62]

There is an ancient tradition of poetry and a poetry competition is held annually on the island.[63] The first attested Socotran poet is thought to be the ninth-century Fatima al-Suqutriyya, a popular figure in Socotran culture.[64]

Socotra Swahili is extinct.[65]

Religion

The earliest account concerning the presence of Christians in Socotra stems from the early-medieval 6th century CE Greek merchant Cosmas Indicopleustes[66] Later the Socotrans joined the Assyrian church.[67] During the tenth century, Arab geographer Abu Muhammad al-Hasan al-Hamdani recorded during his visits that most of the islanders were Christian.

Christianity in Socotra went into decline when the Mahra sultanate took power in the 16th century, and the populace had become mostly Muslim by the time the Portuguese arrived later that century.[68] An 1884 edition of Nature, a science journal, writes that the disappearance of Christian churches and monuments can be accounted for by a Wahhabi excursion to the island in 1800.[69] Today the only remnants of Christianity are some cross engravings from the first century CE, a few Christian tombs, and some church ruins.[70]

Genetics

The majority of male residents on Socotra are reported to be in the J* subclade of Y-DNA haplogroup J. Several of the female lineages, notably those in mtDNA haplogroup N, are unique to the island.[71]

Administrative divisions

Previously, the archipelago pertained to the Hadhramaut Governorate. In 2013, however, the archipelago was removed from the Hadramaut Governorate and the Socotra Governorate was created, consisting of the districts of:

- Hidaybu, with a population of 32,285 and a district seat at Hadibu, consisting of the eastern two-thirds of the main island of Socotra;

- Qalansiyah wa 'Abd-al-Kūrī, with a population of 10,557 and a district seat at Qulensya, consisting of the minor islands of the archipelago (the island of 'Abd-al-Kūrī chief among them) and the western third of the main island.

Economy

The primary occupations of the people of Socotra have traditionally been fishing, bee keeping, animal husbandry, and the cultivation of dates.[72]

Monsoons long made the archipelago inaccessible from June to September each year. In July 1999, however, a new airport opened Socotra to the outside world all year round. There was regular service to and from Aden and Sana'a until the start of the civil war in 2015. All scheduled commercial flights made a technical stop at Riyan-Mukalla Airport. Socotra Airport is located about 12 kilometres (7+1⁄2 miles) west of the main city, Hadibu, and close to the third-largest town in the archipelago, Qād̨ub.[73] Diesel generators make electricity widely available in Socotra. A paved road runs along the north shore from Qulansiyah to Hadibu and then to the DiHamri area; and another paved road, from the northern coast to the south through the Dixsam Plateau.[74]

Some residents raise cattle and goats. The chief export products of the island are dates, ghee, tobacco, and fish.[75]

At the end of the 1990s, a United Nations Development Program was launched to provide a close survey of the island of Socotra.[76] The project called Socotra Governance and Biodiversity Project have listed following goals from 2009:

- Local governance support

- Development and implementation of mainstreaming tools

- Strengthening non-governmental organizations' advocacy

- Direction of biodiversity conservation benefits to the local people

- Support to the fisheries sector and training of professionals

Transport

Public transport on Socotra is limited to a few minibuses; car hire usually means hiring a 4WD car and a driver.[77][78]

Transport is a delicate matter on Socotra as road construction is considered locally to be detrimental to the island and its ecosystem. In particular, damage has occurred via chemical pollution from road construction while new roads have resulted in habitat fragmentation.[79]

The only port on Socotra is 5 kilometres (3 miles) east of Hadibu. Ships connect the port with the Yemeni coastal city of Mukalla. The journey takes 2–3 days and the service is used mostly for cargo.[80] The UAE funded the modernization of the port on Socotra.[81] After cyclones hit Socotra in November 2015, the Emirates Red Crescent set up a lighting system and built a fence in the airport.[82]

Yemenia and Felix Airways flew from Socotra Airport to Sana'a and Aden via Riyan Airport. As of March 2015, due to ongoing civil war involving Saudi Arabia's Air Force, all flights to and from Socotra were cancelled.[83]

However, during the deployment of Emirati troops and aid to the Island, multiple flight connections were made between Abu Dhabi and Hadibu as part of Emirati effort to provide Socotra residents with access to free healthcare and provide work opportunities.[84]

Currently, there are scheduled flights from Cairo and Abu Dhabi to Socotra once a week.[85]

Tourism

The airport for Socotra was built in 1999. Before this modest airport, the island could only be reached by a cargo ship. The ideal time to visit Socotra is from October to April; the remaining months usually have heavy monsoon rainfall, making it difficult for tourists; flights also usually get cancelled.[86] The island lacks any well-established hotels, although there are a few guesthouses for the travelers to stay during their short visits.[87] Due to the Yemeni Civil War that started in 2015, tourism to Socotra Island has been affected. The island received over 1,000 tourists each year until 2014.[88]

Tourism to the island has increased over the years as many operators have started offering trips to the island, which Gulf Today claimed “will become a dream destination despite the country's conflict”. In May 2021, the Ministry of Information stated that the UAE is violating the island and has been planning to control it for years. It is running illegal trips for foreign tourists without taking any permission from the Yemeni government.[89] UAE is operating a weekly direct flight from Abu Dhabi to Socotra Island every Tuesday via Air Arabia.

Gallery

- Other sights

.jpg.webp) Wadi Dirhur canyon on the Diksam Plateau

Wadi Dirhur canyon on the Diksam Plateau Ar'ar spot

Ar'ar spot

See also

- Galápagos Islands, an archipelago of Ecuador which is also famous for its isolated geography and plant and animal species

- Masirah Island, another island with a rugged terrain off the coast of the Arabian Peninsula

- List of islands of Yemen

References

- "Socotra Archipelago".

- "Socotra Definition & Meaning". dictionary.com. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- Burrowes, Robert D. (2010). Historical Dictionary of Yemen. Scarecrow Press. pp. 361–362. ISBN 978-0-8108-5528-1.

- Robinson, Peg; Hestler, Anna; Spilling, Jo-Ann (2019). Yemen. Cavendish Square. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-50264-162-5.

- "Socotra islands scenery in Yemen". en.youth.cn. China Youth International. 25 April 2008. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- "Paradise Has an Address: Socotra - Geography". socotra.cz. Socotra Z.S. Society. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- Huntingford, George Wynn Brereton (1980). The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. Hakluyt Society. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-904180-05-3.

- Abrams, Avi (4 September 2008). "The Most Alien-Looking Place on Earth". Dark Roasted Blend.

- "EU to protect Socotra archipelago environment". Saba Net. Yemen News Agency (SABA). 15 April 2008.

- "Yemen's Socotra, isolated island at strategic crossroads". The Economic Times. 7 June 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- "Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Ancient South Arabia through History". www.cambridgescholars.com. pp. 5–6. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

"As for Śakūrid (S³krd), this name appears to be the basis of the Greek name for Soqoṭrā, Dioskouridēs, via a reconstructed *Dhū-Śakūrid.12

- Sanjeev Sanyal Land of the Seven Rivers: A Brief History of India’s Geography. Penguin Books (2013), p. 112

- A Historical Genealogy of Socotra as an Object of Mythical Speculation, Scientific Research & Development Experiment.

- Zhukov, Valery A. (2014) The Results of Research of the Stone Age Sites in the Island of Socotra (Yemen) in 2008-2012. - Moscow: Triada Ltd. 2014, pps 114, ill. 134 (in Russian) ISBN 978-5-89282-591-7.

- Great Britain. Naval Intelligence Division (2005). "Appendix: Socotra". Western Arabia and the Red Sea. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. p. 611. ISBN 9781136209956.

- Bukharin, Mikhail D.; De Geest, Peter; Dridi, Hédi; Gorea, Maria; Jansen Van Rensburg, Julian; Robin, Christian Julien; Shelat, Bharati; Sims-Williams, Nicholas; Strauch, Ingo (2012). Strauch, Ingo (ed.). Foreign Sailors on Socotra. The inscriptions and drawings from the cave Hoq. Bremen: Dr. Ute Hempen Verlag. p. 592. ISBN 978-3-934106-91-8.

- Martin, E. G. (1974). "Mahdism and holy wars in Ethiopia before 1600". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 4: 114. JSTOR 41223140.

- G. Rex Smith, Ibn al-Mujāwir on Dhofar and Socotra, in: Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, Vol. 15, 1985.

- Photo from ‘The Isle of Frankincense’ by Charles K. Moser, formerly United States Consul-General to Aden, Arabia. Page 271 in The National Geographic Magazine, January to June 1918, Vol. XXXIII, 266-278.

- Diffie, Bailey Wallys; Winius, George Davison (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese empire, 1415–1580. University of Minnesota Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-8166-0782-2.

- Bowersock, Glen Warren; Brown, Peter; Grabar, Oleg (1999). Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press. p. 753. ISBN 978-0674511736.

- A Collection of Treaties, Engagements and Sunnuds related to India and Neighbouring Countries, Calcutta, 1909, volume VIII, page 185.

- Yemen: Cyclones Chapala and Megh Flash Update 11 (PDF) (Report). United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 19 November 2015. ReliefWeb. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- "Yemen officials say Emiratis boost forces on Socotra island". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2 May 2018.

- "Yemen PM: Crisis over UAE deployment to Socotra over". Al Jazeera.

- "Yemen, UAE Agree on Deal Over Socotra". Albawaba News.

- Aziz El Yaakoubi (9 May 2019). "Yemen government accuses UAE of landing separatists on remote island". Reuters.

- "Second army regiment rebels against Yemen government in Socotra". Middle East Monitor. 28 February 2020.

- Mukhashaf, Mohammed; El Yaakoubi, Aziz (21 June 2020). Kasolowsky, Raissa (ed.). "Yemen separatists seize remote Socotra island from Saudi-backed government". Reuters.

On Saturday, the STC announced it had seized government facilities and military bases on the main island of Socotra, a sparsely populated archipelago which sits at the mouth of the Gulf of Aden on one of the world's busiest shipping lanes.

- UAE withdrawal from Aden in 2019 Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- UAE building military camps on Yemen's Socotra island Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- UAE and Saudi Arabia soft-hard power games in Socotra on 2 May 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- Yemen president says UAE acting like occupiers of 12 May 2017. Retrieved: 20 January 2023.

- "Socotra Archipelago – a lifeboat in the sea of changes: advancement in Socotran insect biodiversity survey" (PDF). Acta Entomologica Musei Nationalis Pragae. 52 (supplementum 2): 1–26.

- Beydoun, Z. R.; Bichan, H. R. (1970). "The Geology of Socotra Island, Gulf of Aden". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 3: 413–466.

- Shobrak, Mohammed; Alsuhaibany, Abdullah; Al-Sagheir, Omer (November 2003). Photographs by Abdullah Alsuhaibany. "Status of Breeding Seabirds in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden" (PDF). PERSGA Technical Series (in English and Arabic). Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: Regional Organization for Conservation of Environment of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden (PERSGA) (8).

- "Natural History". DBT Socotra Adventure Tour. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- Sand dunes of the NE-coast Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- Elie, Serge D. (2008). "The Waning of Soqotra's Pastoral Community: Political Incorporation as Social Transformation". Human Organization. 67 (3): 335–345. doi:10.17730/humo.67.3.lm86541uv4765823.

- "Socotra Fauna and Flora".

- "Socotra High Point, Yemen". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- Scholte, Paul, and, De Geest, Peter; ‘The climate of Socotra Island (Yemen): A first-time assessment of the timing of the monsoon wind reversal and its influence on precipitation and vegetation patterns’; Journal of Arid Environments, vol. 74, issue 11 (November 2010); pp. 1507-1515

- Fritz, Angela (5 November 2015). "The mediocre model forecasts of Cyclone Chapala's rainfall over Yemen".

- "Klimatafel von Sokotra (Suqutrá), Insel / Arabisches Meer / Jemen" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- FACTBOX-Socotra, jewel of biodiversity in Arabian Sea. Reuters, 2008-04-23

- Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "1 – Native plants and animals – overview – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". www.teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- Burdick, Alan (25 March 2007). "The Wonder Land of Socotra". T Magazine. New York: New York Times. Retrieved 9 November 2009.

- Miller, A.G.; Morris, M. (2004). Ethnoflora of the Socotra Archipelago. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.

- Kingdon, Jonathan (1989). Island Africa: The Evolution of Africa's Rare Plants and Animals. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 38–42. ISBN 978-0-691-08560-9.

- Vasconcelos R, Montero-Mendieta S, Simó-Riudalbas M, Sindaco R, Santos X, et al. (2016) Unexpectedly High Levels of Cryptic Diversity Uncovered by a Complete DNA Barcoding of Reptiles of the Socotra Archipelago. PLOS ONE 11(3): e0149985. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0149985

- Apel, M. and Brandis, D. 2000. A new species of freshwater crab (Crustacea: Brachyura: Potamidae) from Socotra Island and description of Socotrapotamon n. gen. Fauna of Arabia 18: 133-144.

- "Endemic Fauna - SOCOTRA.CZ". www.socotra.cz. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- "Yemen Endemic Mammals Checklist". lntreasures.com. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Bicyclus, Site of Markku Savela

- "UAE organisation delivers cooking gas to Socotra residents to prevent deforestation". The National. 2 December 2018.

- Schurhammer, Georg (1982). Francis Xavier; His Life, His Times: India, 1541–1544. Vol. 2. Jesuit Historical Institute. p. 122.

- Lockyer, Norman, ed. (1884). "Socotra". Nature. 29 (755): 575–576. Bibcode:1884Natur..29R.575.. doi:10.1038/029575b0.

- Gintsburg, Sarali; Esposito, Eleonora (2022). "The Asymmetric Linguistic Identities of African Soqotris". Language and Identity in the Arab World. Routledge. ISBN 9781003174981.

- "Final Census Results2004: The General Frame of the Population Final Results (First Report)". The General Population Housing and Establishment Census2004. Central Statistical Organisation. 6 January 2007. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- "Default Page". www.socotraproject.org.

- Mansur Mirovalev (2015). "Russian Roots and Yemen's Socotra Language". Al-Jazeera. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- Rupert Hawksley (5 January 2019). "How the Yemeni island of Sokotra is forging its own future". The National: Arts and Culture. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- Morris, Miranda J. (1 January 2013). "The use of 'veiled language' in Soqoṭri poetry". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 43: 239–244. JSTOR 43782882.

- Serge D. Elie, 'Soqotra: South Arabia’s Strategic Gateway and Symbolic Playground', British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 33.2 (November 2006), 131-60, doi:10.1080/13530190600953278 (p. 158 n. 105).

- Maho, Jouni Filip (4 June 2009). "G40 : Swahili Group". New Updated Guthrie List Online (2nd ed.). p. 49. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

G411 * . † – Socotra Swahili

- Jansen van Rensburg, Julian (2018). "Rock Art of Soqotra, Yemen: A Forgotten Heritage Revisited". The Artist and Journal of Home Culture. 7: 99.

- "Socotra history :: Socotra Eco-Tours". www.socotra-eco-tours.com. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- "The history of Socotra". www.socotraislandadventure.com. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- Lockyer, Sir Norman (1 January 1884). Nature. Nature Publishing Group.

- "Socotra history :: Socotra Eco-Tours". www.socotra-eco-tours.com.

- Černý, Viktor; Pereira, Luísa; Kujanová, Martina; Vašíková, Alžběta; Hájek, Martin; Morris, Miranda; Mulligan, Connie J. (April 2009). "Out of Arabia—The settlement of Island Soqotra as revealed by mitochondrial and Y chromosome genetic diversity". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 138 (4): 439–47. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20960. PMID 19012329.

- "Welcome to one of the most exotic islands in the world - Al-Monitor: Independent, trusted coverage of the Middle East". www.al-monitor.com. 2 April 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- "aviationweather.gov". Archived from the original on 14 January 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- Paved roas in Socotra Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- Economy of Socotra Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- "Default Page". www.socotraproject.org.

- "Default Page". www.socotraproject.org.

- Holmes, Oliver (23 June 2010). "Socotra: The Other Galápagos Awaits Tourists". Time. Archived from the original on 25 June 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- Lisa, Banfield. "Past and present human impacts on the biodiversity of Socotra Island - Paper" (PDF). www.friendsofsoqotra.org.

- Maritime transport to Socotra Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- "#UAE National Day 46: WAM Report 6 - UAE aid to Yemen". ReliefWeb. 28 November 2017.

- Dajjani, Hassan. "The Lost Paradise of Socotra". The National.

- Ghattas, Abir. "Yemen's No Fly Zone: Thousands of Yemenis are Stranded Abroad". Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- "Socotra island: The Unesco-protected 'Jewel of Arabia' vanishing amid Yemen's civil war". The Independent. 2 May 2018.

- Flights to Socotra Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- Burdick, Alan (25 March 2007). "The Wonder Land of Socotra, Yemen". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- Kedem, Shoshana. "Tourism In The Time Of Conflict: Yemeni Island Of Socotra Is Open To Travelers | Inc. Arabia". Inc. Arabia. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- "Wanna go to Socotra? Good luck at the moment". The Adventures of Lil Nicki. 6 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- "UAE operating illegal tourist trips to Yemen's Socotra". Middle East Monitor. 10 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

Further reading

- Agafonov, Vladimir (2007). "Temethel as the Brightest Element of Soqotran Folk Poetry". Folia Orientalia. 42/43 (2006/07): 241–249.

- Agafonov, Vladimir (2013). Mehazelo – Cinderella of Socotra. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1482319224.

- Botting, Douglas (2006) [1958]. Island of the Dragon's Blood (2nd ed.). Steve Savage Publishers Limited. ISBN 978-1-904246-21-3.

- Burdick, Alan (25 March 2007). "The Wonder Land of Socotra, Yemen". The New York Times.

- Casson, Lionel (1989). The Periplus Maris Erythraei. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04060-8.

- Cheung, Catherine; DeVantier, Lyndon (2006). Van Damme, Kay (ed.). Socotra: A Natural History of the Islands and their People. Odyssey Books & Guides. ISBN 978-962-217-770-3.

- Doe, D. Brian (1970). Field, Henry; Laird, Edith M. (eds.). Socotra: An Archaeological Reconnaissance in 1967. Miami: Field Research Projects.

- Doe, D. Brian (1992). Socotra: Island of Tranquility. London: Immel.

- Elie, Serge D. (2004). "Hadiboh: From Peripheral Village to Emerging City". Chroniques Yemenites. 12.

- Elie, Serge D. (November 2006). "Soqotra: South Arabia's Strategic Gateway and Symbolic Playground". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 33 (2): 131–160. doi:10.1080/13530190600953278. ISSN 1353-0194. S2CID 129912477.

- Elie, Serge D. (June 2007). The Waning of a Pastoralist Community: An Ethnographic Exploration of Soqotra as a Transitional Social Formation (D.Phil Dissertation thesis). University of Sussex.

- Elie, Serge D. (2008). "The Waning of Soqotra's Pastoral Community: Political Incorporation as Social Transformation". Human Organization. 67 (3): 335–345. doi:10.17730/humo.67.3.lm86541uv4765823.

- Elie, Serge D. (2009). "State-Community Relations in Yemen: Soqotra's Historical Formation as a Sub-National Polity". History and Anthropology. 20 (4): 363–393. doi:10.1080/02757200903166459. S2CID 111387231.

- Elie, Serge D. (2010). "Soqotra: The Historical Formation of a Communal Polity". Chroniques Yéménites. 16 (16): 31–55. doi:10.4000/cy.1766.

- Elie, Serge D. (2012). "Fieldwork in Soqotra: The Formation of a Practitioner's Sensibility". Practicing Anthropology. 34 (2): 30–34. doi:10.17730/praa.34.2.7279k63434142762.

- Elie, Serge D. (2012). "Cultural Accommodation to State Incorporation: Language Replacement on Soqotra Island". Journal of Arabian Studies. 2 (1): 39–57. doi:10.1080/21534764.2012.686235. S2CID 144803493.

- Miller, A.G. & Morris, M. (2004) Ethnoflora of the Socotra Archipelago. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.

- Naumkin, V. V.; Sedov, A. V. (1993). "Monuments of Socotra". In Boussac, Marie-Françoise; Salles, Jean-François (eds.). Athens, Aden, Arikamedu: Essays on the interrelations between India, Arabia and the Eastern Mediterranean. Delhi: Manohar. pp. 193–250. ISBN 978-81-7304-079-5.

- Peutz, Nathalie (2018). Islands of Heritage: Conservation and Transformation in Yemen. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9781503607156.

- Schoff, Wilfred H. (1974) [1912]. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (2nd. ed.). New Delhi: Oriental Books Reprint Corporation.

- Zhukov, Valery A. (2014). The Results of Research of the Stone Age Sites in the Island of Socotra (Yemen) in 2008-2012 (in Russian). Moscow: Triada. ISBN 978-5-89282-591-7.

External links

- LA Times photogallery

- Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh: Soqotra's Misty Future (see page 5 for information on dragon's blood)

- Global organisation of Friends for Soqotra in any aspect based in Edinburgh, Scotland

- Audio interview with Socotra resident

- Carter, Mike. "The land that time forgot", The Observer. Sunday, April 16, 2006.

- A Historical Genealogy of Socotra as an Object of Mythical Speculation, Scientific Research & Development Experiment

- SCF Organisation

- An article in T Style Magazine – NYTimes

- "Suḳuṭra" in the Encyclopaedia of Islam

- Socotra Information Project

- "15 Pictures of 'The Most Alien-Looking Place on Earth'"—photo essay

- Socotra: The Hidden Land—Documentary film of the Island of Socotra

.jpg.webp)