Socialist League (UK, 1885)

The Socialist League was an early revolutionary socialist organisation in the United Kingdom. The organisation began as a dissident offshoot of the Social Democratic Federation of Henry Hyndman at the end of 1884. Never an ideologically harmonious group, by the 1890s the group had turned from socialism to anarchism,[1] and disbanded in 1901.

Socialist League | |

|---|---|

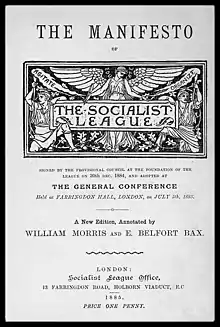

The cover of the Socialist League's manifesto of 1885 featured art by Walter Crane, a member of the group. | |

| Abbreviation | SL |

| Leader | William Morris |

| Secretary | John Lincoln Mahon (1884–1885) Henry Halliday Sparling (1885–1886) Henry Alfred Barker (1886–1888) Fred Charles (1888) Frank Kitz (1888–1890) |

| Founders | |

| Founded | 27 December 1884 |

| Dissolved | 1901 |

| Split from | Social Democratic Federation |

| Succeeded by | Bloomsbury Socialist Society |

| Headquarters | 24 Great Queen Street, London |

| Newspaper | Commonweal |

| Membership (1887) | 550 |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Far-left |

| International affiliation | Second International |

Organizational history

Origins

Until March 1884, the members of the Democratic Federation, forerunner of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), worked together in harmony. The new organisation had expected to make rapid headway with existing radical workingmen's organisations but few chose to join the SDF. Early enthusiasm gave way to disappointment and introspection. Personal relationships began to loom large among the small group's leading members. The personal vanity and domineering attitude of the organisation's founder, Henry Hyndman, along with his nationalism and fixation on parliamentary politics, were the leading causes of the internal acrimony.[2]

By the end of 1884, a group of SDF members sought to remove Hyndman from his position as party leader in December Executive Council meetings. A resolution to censure Hyndman passed by a vote of 10 to 8.[3] The anti-Hyndman dissidents handed in their prepared letter of resignation, believing the federation's lack of fraternal cooperation to be irreconcilable.[4] The 10 seceding members of the old SDF Executive Council issued a statement To Socialists in January 1885 explaining their perspective.[5]

Early in 1885, the secessionists established themselves in a new organisation called the Socialist League. Several SDF branches, such as those in East London, Hammersmith, and Leeds, joined the new group. In Scotland the Scottish Land and Labour League severed its connection with the SDF to join the new organisation.[6] Several important individuals in the movement such as author Edward Carpenter and artist Walter Crane also chose to cast their lot with the fledgling Socialist League.

In February 1885 the new party established its official journal, a newspaper called Commonweal. This publication was initially published monthly but was soon converted into a weekly.[7] Editor of the publication was William Morris, who paid the paper's operating deficit out of pocket.[8]

Development

The Socialist League was a heterogeneous organisation, including Fabians, Christian Socialists, anarchists, and Marxist revolutionary socialists. While the Marxists tolerated the earnest ethical socialists, the anarchists concerned them, with memories of the role of the anarchist schism in the First International still fresh in their memory. Eleanor Marx was one of the Socialist League leaders who was particularly concerned about the place of the largely non-English anarchists in the new party.[9]

The Socialist League was involved in the fight for the right of free speech in London during 1885 and 1886. Whereas religious organisations such as the Salvation Army were allowed to preach in the streets, the London Metropolitan Police banned the Socialists from similar activities. Members of the Socialist League and their rivals the SDF simply continued to speak and to incur fines, attracting public attention, until the authorities made the decision that their prosecution was counterproductive and stopped their interference. Thereafter, public interest in the street meetings rapidly evaporated.[10]

While the political contributions of the tiny Socialist League were not measurable, it did have a lasting literary impact. The newspaper of the Socialist League, The Commonweal, provided the venue for first publication of a number of original writings, including the serialized novels of William Morris, Dream of John Ball and News from Nowhere.[11]

In 1887, the League's membership split ideologically into three factions: anarchists, parliamentary-oriented socialists, and anti-parliamentary socialists.[12]

Anarchist control

Around the middle of this same year, 1887, anarchists began to outnumber socialists in the Socialist League.[13] The 3rd Annual Conference, held in London on 29 May 1887 marked the change, with a majority of the 24 delegates voting in favor of an anarchist-sponsored resolution declaring that "This conference endorses the policy of abstention from parliamentary action, hitherto pursued by the League, and sees no sufficient reason for altering it."[14] Frederick Engels, living in London and a very interested observer in the League's affairs, saw William Morris' role as decisive. Morris, a benefactor of the Commonweal, declared on principle that he would quit if the League took any parliamentary action.[15]

Many of the group's international socialists began to leave. In August 1888, the London branch of the Socialist League, which included Eleanor Marx and Edward Aveling, seceded in favor of establishing itself as an independent organization, the Bloomsbury Socialist Society.[16] By the end of 1888 many other parliamentary-oriented individuals had exited the Socialist League to return to the SDF, with others who remained hostile to the SDF's parliamentary emphasis choosing to involve themselves in the burgeoning movement for so-called "New Unionism."[13] As the socialist factions left, the anarchist faction solidified its hold on the organisation.

By 1889, the anarchist wing had completely captured the organisation. William Morris was stripped of the editorship of Commonweal in favor of Frank Kitz, an anarchist workman. Morris was left to foot the ongoing operating deficit of the publication, some £4 per week[13] — this at a time when £150 per year was the average annual family income in the kingdom.[17] By the autumn of 1890, Morris had had enough and he, too, withdrew from the Socialist League.

Disestablishment

The anarchist movement had newspapers of its own, including the journals Liberty and Freedom.[18]

The William Morris Society "reformed" the Hammersmith branch for one day on the TUC March for the Alternative on 26 March 2011.[19] The banner was paraded again on 20 October 2012.

Notable members

Secretaries

- 1885: John Lincoln Mahon

- 1885: Henry Halliday Sparling

- 1886: Henry Alfred Barker

- 1888: Fred Charles

- 1888: Frank Kitz

- 1890: Woolf Wess

Conferences of the Socialist League

Year Name Location Dates Delegates 1885 1st Annual Conference Farringdon Hall, London 5 July 1886 Semi-Annual Conference 25 January 1886 2nd Annual Conference 13 June 1887 3rd Annual Conference 13 Faringdon Road, London 29 May 24 1888 4th Annual Conference 13 Faringdon Road, London 20 May 1889 5th Annual Conference June 1890 6th Annual Conference Communist Club, Tottenham Court Road, London 25 May 14

Data from International Institute of Social History, "Finding Aid for the Socialist League Archive," supplemented by Kapp, Eleanor Marx: Volume 2, passim and Marx-Engels Collected Works, Volume 48, passim.

Footnotes

- James C. Docherty. Historical dictionary of socialism. The Scarecrow Press Inc. London 1997. pg. 174

- Beer 1929, pp. 252–253; Kapp 1976, p. 55.

- Kapp 1976, p. 59.

- Kapp 1976, pp. 59–60.

- Kapp 1976, pp. 63–64.

- Clayton 1926, p. 31.

- Beer 1929, p. 255.

- Beer 1929, pp. 255–256.

- Kapp 1976, pp. 68–69.

- Clayton 1926, p. 33.

- Clayton 1926, p. 39.

- Irina Shikanyan, Notes to Marx-Engels Collected Works: Volume 47, pg. 595, fn. 346.

- Beer 1929, p. 256.

- Marx-Engels Collected Works: Volume 48. New York: International Publishers, 2001; pg. 538, fn. 95.

- Frederick Engels to Friedrich Sorge, 4 June 1887. Reprinted in Marx-Engles Collected Works: Volume 48, pg. 70.

- Marx-Engels Collected Works: Vol. 48, pg. 611, fn. 642.

- Clayton 1926, p. 44.

- Clayton 1926, p. 68.

- "The William Morris Society and the TUC Day of Action". Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

Bibliography

- Beer, Max (1929). A History of British Socialism. Vol. 2. London: George Bell & Sons. pp. 253–258. OCLC 491581602.

- Clayton, Joseph (1926). The Rise and Decline of Socialism in Great Britain, 1884–1924. London: Faber and Faber. pp. 9–53. OCLC 252439938.

- Kapp, Yvonne (1976). Eleanor Marx. Vol. 2. London: Lawrence & Wishart. ISBN 0853153701. OCLC 658156891.

External links

- Manifesto of the Socialist League, Commonweal, February 1885. William Morris Internet Archive, Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- Socialist League (UK) Archives, at the International Institute of Social History. Retrieved 19 May 2018.