Scottish society in the Middle Ages

Scottish society in the Middle Ages is the social organisation of what is now Scotland between the departure of the Romans from Britain in the fifth century and the establishment of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century. Social structure is obscure in the early part of the period, for which there are few documentary sources. Kinship groups probably provided the primary system of organisation and society was probably divided between a small aristocracy, whose rationale was based around warfare, a wider group of freemen, who had the right to bear arms and were represented in law codes, above a relatively large body of slaves, who may have lived beside and become clients of their owners.

From the twelfth century there are sources that allow the stratification in society to be seen in detail, with layers including the king and a small elite of mormaers above lesser ranks of freemen and what was probably a large group of serfs, particularly in central Scotland. In this period the feudalism introduced under David I meant that baronial lordships began to overlay this system, the English terms earl and thane became widespread. Below the noble ranks were husbandmen with small farms and growing numbers of cottars and gresemen (grazing tenants) with more modest landholdings. The combination of agnatic kinship and feudal obligations has been seen as creating the system of clans in the Highlands in this era. Scottish society adopted theories of the three estates to describe its society and English terminology to differentiate ranks. Serfdom disappeared from the records in the fourteenth century and new social groups of labourers, craftsmen and merchants, became important in the developing burghs. This led to increasing social tensions in urban society, but, in contrast to England and France, there was a lack of major unrest in Scottish rural society, where there was relatively little economic change.

Early Middle Ages

Kinship

The primary unit of social organisation in Germanic and Celtic Europe of the early Middle Ages was the kin group and this was probably the case in early Medieval Scotland.[1] The mention of descent through the female line in the ruling families of the Picts in later sources and the recurrence of leaders clearly from outside of Pictish society, has led to the conclusion that their system of descent was matrilineal. However, this has been challenged by a number of historians who argue that the clear evidence of awareness of descent through the male line suggests that this more likely to indicate an agnatic system of descent, typical of Celtic societies and common throughout North Britain.[2][3]

Social structure

Scattered evidence, including the records in Irish annals and the visual images like the warriors depicted on the Pictish stone slabs at Aberlemno, Forfarshire and Hilton of Cadboll, in Easter Ross, suggest that in Northern Britain, as in Anglo-Saxon England, the upper ranks of society formed a military aristocracy, whose status was largely dependent on their ability and willingness to fight.[1] Below the level of the aristocracy it is assumed that there were non-noble freemen, working their own small farms or holding them as free tenants.[4] There are no surviving law codes from Scotland in this period,[5] but such codes in Ireland and Wales indicate that freemen had the right to bear arms, represent themselves in law and to receive compensation for murdered kinsmen.[6]

Slavery

Indications are that society in North Britain contained relatively large numbers of slaves, often taken in war and raids, or bought, as St. Patrick indicated the Picts were doing, from the Britons in Southern Scotland.[7] Slave owning probably reached relatively far down in society, with most rural households containing some slaves. Because they were taken relatively young, many slaves would have been more integrated into their societies of capture than their societies of origin, in terms of both culture and language. Living and working beside their owners in practice they may have become members of a household without the inconvenience of the partible inheritance rights that divided estates. Where there is better evidence from England and elsewhere, it was common for slaves who survived to middle age to gain their freedom, with such freedmen often remaining clients of the families of their former masters.[8]

Religious life

In the Early Medieval era most evidence of religious practice comes from monks and is heavily biased towards monastic life. From this can be seen the daily cycle of prayers and the celebration of the Mass. There was also the business of farming, fishing and in the islands, seal hunting. Literary life revolved around the contemplation of texts and the copying of manuscripts. Libraries were of great importance to monastic communities. The one at Iona may have been exceptional, but it demonstrates that the monks were part of the mainstream of European Christian culture. Less well recorded, but as significant, was the role of bishops and their clergy. Bishops dealt with the leaders of the tuath, ordained clergy and consecrated churches. They also had responsibilities for the poor, hungry, prisoners, widows and orphans. Priests carried out baptisms, masses and burials. They also prayed for the dead and offered sermons. They anointed the sick with oil, brought communion to the dying and administered penance to sinners. Early local churches were widespread, but since they were largely made of wood,[9] like that excavated at Whithorn,[10] the only evidence that survives for most is in place names that contain words for church, including cill, both, eccles and annat, but others are indicated by stone crosses and Christian burials.[9] Beginning on the west coast and islands and spreading south and east, these were replaced with basic masonry-built buildings.[11]

Education

In the Early Middle Ages, Scotland was overwhelmingly an oral society and education was verbal rather than literary. Fuller sources for Ireland of the same period suggest that there may have been filidh, who acted as poets, musicians and historians, often attached to the court of a lord or king, and passed on their knowledge in Gaelic to the next generation.[12][13] After the "de-gallicisation" of the Scottish court from the twelfth century, a less highly regarded order of bards took over these functions and they would continue to act in a similar role in the Highlands and Islands into the eighteenth century. They often trained in bardic schools, of which a few, like the one run by the MacMhuirich dynasty, who were bards to the Lord of the Isles,[14] existed in Scotland and a larger number in Ireland, until they were suppressed from the seventeenth century.[13] Much of their work was never written down and what survives was only recorded from the sixteenth century.[12] The establishment of Christianity brought Latin to Scotland as a scholarly and written language. Monasteries served as major repositories of knowledge and education, often running schools and providing a small educated elite, who were essential to create and read documents in a largely illiterate society.[15]

High Middle Ages

Ranks

The legal tract known as Laws of the Brets and Scots, probably compiled in the reign of David I (1124–53), underlines the importance of the kin group as entitled to compensation for the killing of individual members. It also lists five grades of man: King, mormaer, toísech, ócthigern and neyfs.[16] The highest rank below the king, the mormaer ("great officer"), was probably composed of about a dozen provincial rulers. Below them the toísech (leader), appear to have managed areas of the royal demesne, or that of a mormaer or abbot, within which they would have held substantial estates, sometimes described as shires.[17] The lowest free rank mentioned by the Laws of the Brets and Scots, the ócthigern (literally, little or young lord), is a term the text does not translate into French.[16] There were probably relatively large numbers of free peasant farmers, called husbandmen in the south and north of the country, but fewer in the lands between the Forth and Sutherland. This changed from the twelfth century, when landlords began to encourage the formation of such a class through paying better wages and deliberate immigration.[17] Below the husbandmen a class of free farmers with smaller parcels of land developed, with cottars and grazing tenants (gresemen).[18] The non-free bondmen, naviti, neyfs or serfs existed in various forms of service, under terms with their origins in Irish practice, including cumelache, cumherba and scoloc who were tied to a lord's estate and unable to leave it without permission, but who records indicate often absconded for better wages or work in other regions, or in the developing burghs.[17]

Feudalism

The feudalism introduced under David I, particularly in the east and south where the crown's authority was greatest, saw the placement of lordships, often based on castles, and the creation of administrative sheriffdoms, which overlay the pattern of administration by local thanes.[19] Land was now held from the king, or a superior lord, in exchange for loyalty and forms of service that were usually military.[20] It also saw the English earl and Latin comes begin to replace the mormaers in the records.[19] However, the imposition of feudalism continued to sit beside existing system of landholding and tenure and it is not clear how this change impacted on the lives of the ordinary free and unfree workers. In places, feudalism may have tied workers more closely to the land, but the predominantly pastoral nature of Scottish agriculture may have made the imposition of a manorial system, based on the English model, impracticable.[20] Obligations appear to have been limited to occasional labour service, seasonal renders of food, hospitality and money rents.[18]

Royal women

A large proportion of the women for who biographical details survive for the Middle Ages, were members of the royal houses of Scotland, either as princesses or queen consorts. Some of these became important figures in the history of Scotland or gained a significant posthumous reputation. There was only one reigning Scottish Queen in this period, the uncrowned and short-lived Margaret, Maid of Norway (r. 1286–90).[21] The first wife called "queen" in Scottish sources is the Anglo-Saxon and German princess Margaret, the wife of Malcolm III, which may have been a title and status negotiated by her relatives. She was a major political and religious figure within the kingdom, but her status was not automatically passed on to her successors, most of whom did not have the same prominence.[22] Ermengarde de Beaumont, the wife of William I acted as a mediator, judge in her husband's absence and is the first Scottish Queen known to have had her own seal.[23]

Monasticism

Some early Scottish monasteries had dynasties of abbots, who were often secular clergy with families, as at Dunkeld and Brechin.[24] Perhaps in reaction to this secularisation, a reforming movement of monks called Céli Dé (lit. "vassals of God"), anglicised as culdees, began in Ireland and spread to Scotland in the late eighth and early ninth centuries. Some Céli Dé took vows of chastity and poverty and while some lived individually as hermits, others lived beside or within existing monasteries.[25] The introduction of continental forms of monasticism to Scotland is associated with Queen Margaret (c. 1045–93). She was in communication with Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury, and he provided a few monks for a new Benedictine abbey at Dunfermline (c. 1070).[24] Subsequent foundations under Margaret's sons, Edgar (r. 1097–1107), Alexander (r. 1107–24) and particularly David I (r. 1124–53), tended to be of the reformed type that followed the lead set by Cluny Abbey in the Loire from the late tenth century. Most belonged to the new religious orders that originated in France in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. These stressed the original Benedictine virtues of poverty, chastity and obedience, but also contemplation and service of the Mass and were followed in various forms by reformed Benedictine, Augustinian and Cistercian houses.[24] This period also saw the introduction of more sophisticated forms of church architecture that had become common on the Continent and in England, known collectively as Romanesque.[26][27]

Saints

One of the main features of Medieval Catholicism was the Cult of Saints. Saints of Irish origin who were particularly revered included various figures called St Faelan and St. Colman, and saints Findbar and Finan.[28] Columba remained a major figure into the fourteenth century and a new foundation was endowed by William I (r. 1165–1214) at Arbroath Abbey and his relics, contained in the Monymusk Reliquary, were handed over to the Abbot's care.[29][30] Regional saints remained important to local identities. In Strathclyde the most important saint was St Kentigern, whose cult (under the pet name St. Mungo) became focused in Glasgow.[31] In Lothian it was St Cuthbert, whose relics were carried across the Northumbria after Lindisfarne was sacked by the Vikings before being installed in Durham Cathedral.[32] After his martyrdom around 1115, a cult emerged in Orkney, Shetland and northern Scotland around Magnus Erlendsson, Earl of Orkney.[33] One of the most important cults in Scotland, that of St Andrew, was established on the east coast at Kilrymont by the Pictish kings as early as the eighth century.[34] The shrine, which from the twelfth century was said to have contained the relics of the saint brought to Scotland by Saint Regulus,[35] began to attract pilgrims from across Scotland, but also from England and further away. By the twelfth century the site at Kilrymont had become known simply as St. Andrews and it became increasingly associated with Scottish national identity and the royal family.[34] Its bishop would supplant that of Dunkeld as the most important in the kingdom and would begin to be referred to as Bishop of Alba.[35] The site was renewed as a focus for devotion with the patronage of Queen Margaret,[29] who also became important after her canonisation in 1250 and after the ceremonial transfer of her remains to Dunfermline Abbey, as one of the most revered national saints.[34]

Schools

In the High Middle Ages there were new sources of education, such as song and grammar schools. These were usually attached to cathedrals or a collegiate church and were most common in the developing burghs. By the end of the Middle Ages grammar schools could be found in all the main burghs and some small towns. Early examples including the High School of Glasgow in 1124 and the High School of Dundee in 1239.[36] There were also petty schools, more common in rural areas and providing an elementary education.[37]

Late Middle Ages

Kinship and clans

The agnatic kinship and descent of late Medieval Scottish society, with members of a group sharing a (sometimes fictional) common ancestor, was often reflected in a common surname in the south. Unlike in England, where kinship was predominantly cognatic (derived through both males and females), women retained their original surname at marriage and marriages were intended to create friendship between kin groups, rather than a new bond of kinship.[38] As a result, a shared surname has been seen as a "test of kinship", providing large bodies of kin who could call on each other’s support. This could help intensify the idea of the feud, which was usually carried out as a form of revenge for the death or injury of a kinsman. Large bodies of kin could be counted on to support rival sides, although conflict between members of kin groups also occurred.[39]

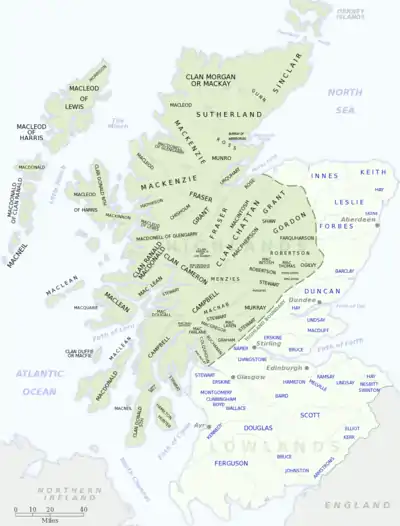

The combination of agnatic kinship and a feudal system of obligation has been seen as creating the Highland clan system, evident in records from the thirteenth century.[40] Surnames were rare in the Highlands until the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In the Middle Ages all members of a clan did not share a name and most ordinary members were usually not related to its head.[41] At the beginning of the era, the head of a clan was often the strongest male in the main sept or branch of the clan, but later, as primogeniture began to dominate, it was usually the eldest son of the last chief.[42] The leading families of a clan formed the fine, often seen as equivalent in status to Lowland gentlemen, providing council to the chief in peace and leadership in war.[43] Below them were the daoine usisle (in Gaelic) or tacksmen (in Scots), who managed the clan lands and collected the rents.[44] In the Isles and along the adjacent western seaboard, there were also buannachann, who acted as a military elite, defending the clan lands from raids and taking part in attacks on clan enemies. Most of the followers of the clan were tenants, who supplied labour to the clan heads and sometimes act as soldiers. In the early modern era they would take the clan name as their surname, turning the clan into a massive, if often fictive, kin group.[42]

Structure

From 1357 onwards parliaments began to be referred to as the Three Estates,[45] adopting the language of social organisation that had developed in France in the eleventh century.[46] It was composed of the clergy, nobles and burgesses,[47] (those that pray, those that fight and those that work). This marked the adoption of a commonplace view of Medieval society as composed of distinct orders.[48] Within these estates there were ranks for which the terminology was increasingly dominated by the Scots language and as a result began to parallel that used in England. This consciousness over status was reflected in military and (from 1430) sumptuary legislation, which set out the types of weapons and armour that should be maintained, and clothes that could be worn, by various ranks.[38]

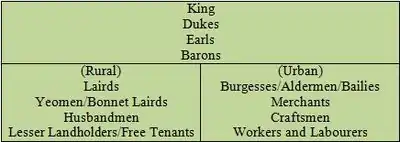

Below the king were a small number of dukes (usually descended from very close relatives of the king) and earls, who formed the senior nobility. Below them were the barons, who held baronial manors from the crown. From the 1440s, fulfilling a similar role were the lords of Parliament, the lowest level of the nobility with the rank-given right to attend the Estates. There were perhaps 40 to 60 of these in Scotland throughout the period.[49] Members of these noble ranks, perhaps particularly those that had performed military or administrative service to the crown, might also be eligible for the status of knighthood.[50] Below these were the lairds, roughly equivalent to the English gentlemen.[49] Most were in some sense in the service of the major nobility, either in terms of landholding or military obligations,[49] roughly half sharing with them their name and a distant and often uncertain form of kinship.[51] Below the lords and lairds were a variety of groups, often ill-defined. These included yeomen, later called by Walter Scott "bonnet lairds", often owning substantial land. Below them were the husbandmen, lesser landholders and free tenants that made up the majority of the working population.[52] Serfdom died out in Scotland in the fourteenth century, although through the system of courts baron landlords still exerted considerable control over their tenants.[51] Society in the burghs was headed by wealthier merchants who often held local office as a burgess, alderman, bailies or as a member of the council. A small number of these successful merchants were dubbed knights for their service by the king by the end of the era, although this seems to have been an exceptional form of civic knighthood that did not put them on a par with landed knights.[53] Below them were craftsmen and workers that made up the majority of the urban population.[54]

Social conflict

Historians have noted considerable political conflict in the burghs between the great merchants and craftsmen throughout the period. Merchants attempted to prevent lower crafts and guilds from infringing on their trade, monopolies and political power. Craftsmen attempted to emphasise their importance and to break into disputed areas of economic activity, setting prices and standards of workmanship. In the fifteenth century a series of statutes cemented the political position of the merchants, with limitations on the ability of residents to influence the composition of burgh councils and many of the functions of regulation taken on by the bailies.[54] In rural society historians have noted a lack of evidence of widespread unrest of the nature of that evidenced the Jacquerie of 1358 in France and the Peasants' Revolt of 1381 in England. This was possibly because in Scotland there was relatively little of the type of change in agriculture, like the enclosure of common land, that could create widespread resentment before the modern era. Instead a major factor was the willingness of tenants to support their betters in any conflict in which they were involved, for which landlords reciprocated with charity and support.[55] Both Highland and border society acquired reputations for lawless activity, particularly the feud. However, more recent interpretations have pointed to the feud as a means of preventing and speedily resolving disputes by forcing arbitration, compensation and resolution.[56]

Popular religion

Traditional Protestant historiography tended to stress the corruption and unpopularity of the late Medieval Scottish church, but more recent research has indicated the ways in which it met the spiritual needs of different social groups.[57][58] Historians have discerned a decline of monastic life in this period, with many religious houses keeping smaller numbers of monks, and those remaining often abandoning communal living for a more individual and secular lifestyle. The rate of new monastic endowments from the nobility also declined in the fifteenth century.[57][59] In contrast, the burghs saw the flourishing of mendicant orders of friars in the later fifteenth century, who, unlike the older monastic orders, placed an emphasis on preaching and ministering to the population. The order of Observant Friars were organised as a Scottish province from 1467 and the older Franciscans and the Dominicans were recognised as separate provinces in the 1480s.[57]

In most Scottish burghs, in contrast to English towns where churches and parishes tended to proliferate, there was usually only one parish church,[60] As the doctrine of Purgatory gained importance in the period, the number of chapelries, priests and masses for the dead within them, designed to speed the passage of souls to Heaven, grew rapidly.[61] The number of altars dedicated to saints, who could intercede in this process, also grew dramatically, with St. Mary's in Dundee having perhaps 48 and St Giles' in Edinburgh over 50.[60] The number of saints celebrated in Scotland also proliferated, with about 90 being added to the missal used in St Nicholas church in Aberdeen.[62] New cults of devotion connected with Jesus and the Virgin Mary began to reach Scotland in the fifteenth century, including the Five Wounds, the Holy Blood and the Holy Name of Jesus. There were also new religious feasts, including celebrations of the Presentation, the Visitation and Mary of the Snows.[60][62]

In the early fourteenth century the Papacy managed to minimise the problem of clerical pluralism, by which clerics held two or more livings, which elsewhere resulted in parish churches being without priests, or serviced by poorly trained and paid vicars and clerks. However, the number of poor clerical livings and a general shortage of clergy in Scotland, particularly after the Black Death, meant that in the fifteenth century the problem intensified.[63] As a result, parish clergy were largely drawn from the lower and less educated ranks of the profession, leading to frequent complaints about their standards of education or ability. Although there is little clear evidence that standards were declining, this would be one of the major grievances of the Reformation.[57] Heresy, in the form of Lollardry, began to reach Scotland from England and Bohemia in the early fifteenth century. Lollards were followers of John Wycliffe (c. 1330–84) and later Jan Hus (c. 1369–1415), who called for reform of the Church and rejected its doctrine on the Eucharist. Despite evidence of a number of burnings of heretics and limited popular support for its anti-sacramental elements, it probably remained a small movement.[64] There were also further attempts to differentiate Scottish liturgical practice from that in England, with a printing press established under royal patent in 1507 to replace the English Sarum Use for services.[60]

Expansion of schools and universities

The number and size of schools seems to have expanded rapidly from the 1380s.[36][37] There was also the development of private tuition in the families of lords and wealthy burghers.[36] The growing emphasis on education cumulated with the passing of the Education Act 1496, which decreed that all sons of barons and freeholders of substance should attend grammar schools to learn "perfyct Latyne". All this resulted in an increase in literacy, but which was largely concentrated among a male and wealthy elite,[36] with perhaps 60 per cent of the nobility being literate by the end of the period.[65] Until the fifteenth century, those who wished to attend university had to travel to England or the continent, and just over a 1,000 have been identified as doing so between the twelfth century and 1410.[66] After the outbreak of the Wars of Independence, with occasional exceptions under safe conduct, English universities were closed to Scots and continental universities became more significant.[66] Some Scottish scholars became teachers in continental universities.[66] This situation was transformed by the founding of the University of St Andrews in 1413, the University of Glasgow in 1450 and the University of Aberdeen in 1495.[36] Initially these institutions were designed for the training of clerics, but they would increasingly be used by laymen who would begin to challenge the clerical monopoly of administrative posts in the government and law. Those wanting to study for second degrees still needed to go elsewhere and Scottish scholars continued to visit the continent and English universities, which reopened to Scots in the late fifteenth century.[66]

Women

Medieval Scotland was a patriarchal society, where authority was invested in men and women had a very limited legal status.[67] How exactly patriarchy worked in practice is difficult to discern.[68] Women could marry from the age of 12 (while for boys it was from 14) and, while many girls from the social elite married in their teens, by the end of the period most in the Lowlands only married after a period of life-cycle service, in their twenties.[69] The extensive marriage bars for kinship meant that most noble marriages necessitated a papal dispensation, which could later be used as grounds for annulment if the marriage proved politically or personally inconvenient, although there was no divorce as such.[70] Separation from bed and board was allowed in exceptional circumstances, usually adultery.[67] In the burghs there were probably high proportions of poor households headed by widows, who survived on casual earnings and the profits from selling foodstuffs or ale.[71] Spinning was an expected part of the daily work of Medieval townswomen of all social classes.[72] In crafts, women could sometimes be apprentices, but they could not join guilds in their own right. Some women worked and traded independently, hiring and training employees, which may have made them attractive as marriage partners.[73] Scotland was relatively poorly supplied with nunneries, with 30 identified for the period to 1300, compared with 150 for England, and very few in the Highlands.[74][75] The Virgin Mary, as the epitome of a wife and mother was probably an important model for women.[76] There is evidence from late Medieval burghs like Perth, of women, usually wives, acting through relatives and husbands as benefactors or property owners connected with local altars and cults of devotion.[73] By the end of the fifteenth century, Edinburgh had schools for girls, sometimes described as "sewing schools", which were probably taught by lay women or nuns.[36][77] There was also the development of private tuition in the families of lords and wealthy burghers, which may have extended to women.[36]

Children

Childhood mortality was high in Medieval Scotland.[78] Children were often baptised rapidly, by laymen and occasionally by midwives, because of the belief that unbaptised children would be damned.[79] It was more normally undertaken in a church and was a means of creating wider spiritual kinship with godparents.[80] Cemeteries may not represent a cross section of Medieval society, but in one Aberdeen cemetery 53 per cent of those buried were under the age of six and in one Linlithgow cemetery it was 58 per cent. Iron deficiency anaemia seems to have been common among children, probably caused by long-term breastfeeding by mothers that were themselves deficient in minerals. Common childhood diseases included measles, diphtheria and whooping-cough, while parasites were also common.[78] In Lowland noble and wealthy society by the fifteenth century the practice of wet-nursing had become common.[79] In Highland society there was a system of fosterage among clan leaders, where boys and girls would leave their parents' house to be brought up in that of other chiefs, creating a fictive bond of kinship that helped cement alliances and mutual bonds of obligation.[81] The majority of children, even in urban centres where opportunities for formal education were greatest, did not attend school.[78] In the families of craftsmen children probably carried out simpler tasks. They might later become apprentices or journeymen.[82] In Lowland rural society, as in England, many young people, both male and female, probably left home to become domestic and agricultural servants, as they can be seen doing in large numbers from the sixteenth century.[83] By the late Medieval era, Lowland society was probably part of the north-west European marriage model, of life-cycle service and late marriage, usually in the mid-20s, delayed by the need to acquire the resources to be able to form a household.[84]

Notes

- C. Haigh, The Cambridge Historical Encyclopedia of Great Britain and Ireland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), ISBN 0521395526, pp. 82–4.

- A. P. Smyth, Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 0748601007, pp. 57–8.

- J. T. Koch, Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2006), ISBN 1851094407, p. 1447.

- J. T. Koch, Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2006), ISBN 1851094407, p. 369.

- D. E. Thornton, "Communities and kinship", in P. Stafford, ed., A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland, c.500-c.1100 (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), ISBN 140510628X, pp. 98.

- J. P. Rodriguez, The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery, Volume 1 (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 1997), ISBN 0874368855, p. 136.

- L. R. Laing, The Archaeology of Celtic Britain and Ireland, c. AD 400–1200 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), ISBN 0521547407, pp. 21–2.

- A. Woolf, From Pictland to Alba: 789 – 1070 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748612343, pp. 17–20.

- G. Markus, "Religious life: early medieval", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 509–10.

- J. R. Hume, Scotland's Best Churches (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-7486-2179-2, p. 1.

- I. Maxwell, A History of Scotland's Masonry Construction in P. Wilson, ed., Building with Scottish Stone (Edinburgh: Arcamedia, 2005), ISBN 1-904320-02-3, pp. 22–3.

- R. Crawford, Scotland's Books: A History of Scottish Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), ISBN 0-19-538623-X.

- R. A. Houston, Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-521-89088-8, p. 76.

- K. M. Brown, Noble Society in Scotland: Wealth, Family and Culture from the Reformation to the Revolutions (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), ISBN 0-7486-1299-8, p. 220.

- A. Macquarrie, Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, p. 128.

- A. Grant, "Thanes and Thanages, from the eleventh to the fourteenth centuries" in A. Grant and K. Stringer, eds., Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community, Essays Presented to G. W. S. Barrow (Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, 1993), ISBN 074861110X, p. 42.

- G. W. S. Barrow, Kingship and Unity: Scotland 1000–1306 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 074860104X, pp. 15–18.

- G. W. S. Barrow, "Scotland, Wales and Ireland in the twelfth century", in D. E. Luscombe and J. Riley-Smith, eds, The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume IV. 1024-c. 1198, part 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), ISBN 0521414113, p. 586.

- A. Grant, "Scotland in the Central Middle Ages", in A. MacKay and D. Ditchburn, (eds), Atlas of Medieval Europe (Routledge: London, 1997), ISBN 0415122317, p. 97.

- A. D. M. Barrell, Medieval Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), ISBN 052158602X, pp. 16–19.

- R. M. Warnicke, Mary Queen of Scots (London: Taylor & Francis, 2012), ISBN 0415291828, p. 9.

- J. Nelson, "Scottish Queenship in the Thirteenth century", in B. K. U. Weiler, J. Burton and P. R. Schofield, eds, Thirteenth-Century England (London: Boydell Press, 2007), ISBN 1843832852, pp. 63–4.

- J. Nelson, "Scottish Queenship in the Thirteenth century", in B. K. U. Weiler, J. Burton and P. R. Schofield, eds, Thirteenth-Century England (London: Boydell Press, 2007), ISBN 1843832852, pp. 66–7.

- A. Macquarrie, Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, pp. 117–128.

- B. Webster, Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity (New York City, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1997), ISBN 0333567617, p. 58.

- M .Perry, M. Chase, J. R. Jacob, M. C. Jacob, T. H. Von Laue, Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society (Cengage Learning, 2012), ISBN 1111831688, p. 270.

- T. W. West, Discovering Scottish Architecture (Botley: Osprey, 1985), ISBN 0-85263-748-9, p. 10.

- G. W. S. Barrow, Kingship and Unity: Scotland 1000–1306 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 074860104X, p. 64.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (Random House, 2011), ISBN 1446475638, p. 76.

- B. Webster, Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity (New York City, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1997), ISBN 0333567617, pp. 52–3.

- A. Macquarrie, Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, p. 46.

- A. Lawrence-Mathers, Manuscripts in Northumbria in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries (Woodbridge: Brewer, 2003), ISBN 0859917657, p. 137.

- H. Antonsson, St. Magnús of Orkney: A Scandinavian Martyr-Cult in Context (Leiden: Brill, 2007), ISBN 9004155805.

- G. W. S. Barrow, Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 4th edn., 2005), ISBN 0748620222, p. 11.

- B. Webster, Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity (New York City, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1997), ISBN 0333567617, p. 55.

- P. J. Bawcutt and J. H. Williams, A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry (Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006), ISBN 1-84384-096-0, pp. 29–30.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (Random House, 2011), ISBN 1-4464-7563-8, pp. 104–7.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 29–35.

- J. W. Armstrong, "The 'fyre of ire Kyndild' in the fifteenth-century Scottish Marches", in S. A. Throop and P. R. Hyams, eds, Vengeance in the Middle Ages: Emotion, Religion and Feud (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2010), ISBN 075466421X, p. 71.

- G. W. S. Barrow, Robert Bruce (Berkeley CA.: University of California Press, 1965), p. 7.

- J. P. Campbell, Popular Culture in the Middle Ages (Madison, WI: Popular Press, 1986), ISBN 0879723394, p. 98, n.

- J. L. Roberts, Clan, King, and Covenant: History of the Highland Clans from the Civil War to the Glencoe Massacre (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2000), ISBN 0748613935, p. 13.

- M. J. Green, The Celtic World (London: Routledge, 1996), ISBN 0415146275, pp. 667.

- D. Moody, Scottish Family History (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Com, 1994), ISBN 0806312688, pp. 99–104.

- D. E. R. Wyatt, "The provincial council of the Scottish church", in A. Grant and K. J. Stringer, Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), ISBN 074861110X, p. 152.

- W. W. Kibler, ed., Medieval France: An Encyclopedia (London: Routledge, 1995), ISBN 0824044444, p. 324.

- P. J. Bawcutt and J. H. Williams, A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry (Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006), ISBN 1843840960, pp. 22.

- J. Goodare, The Government of Scotland, 1560–1625 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), ISBN 0199243549, p. 42.

- A. Grant, "Service and tenure in late medieval Scotland 1324–1475" in A. Curry and E. Matthew, eds, Concepts and Patterns of Service in the Later Middle Ages (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2000), ISBN 0851158145, pp. 145–65.

- K. Stevenson, Chivalry and Knighthood in Scotland, 1424–1513 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2006), ISBN 1843831929, pp. 13–15.

- J. Goodacre, State and Society in Early Modern Scotland (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), ISBN 019820762X, pp. 57–60.

- A. Grant, "Late medieval foundations", in A. Grant and K. J. Stringer, eds, Uniting the Kingdom?: the Making of British History (London: Routledge, 1995), ISBN 0415130417, p. 99.

- K. Stevenson, "Thai war callit knynchtis and bere the name and the honour of that hye ordre: Scottish knighthood in the fifteenth century", in L. Clark, ed., Identity and Insurgency in the Late Middle Ages (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2006), ISBN 1843832704, p. 38.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 48–9.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 50–1.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 28 and 35-9.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 76–87.

- D. M. Palliser, The Cambridge Urban History of Britain: 600–1540 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), ISBN 0521444616, pp. 349–50.

- Andrew D. M. Barrell, Medieval Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), ISBN 052158602X, p. 246.

- P. J. Bawcutt and J. H. Williams, A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry (Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006), ISBN 1843840960, pp. 26–9.

- Andrew D. M. Barrell, Medieval Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), ISBN 052158602X, p. 254.

- C. Peters, Women in Early Modern Britain, 1450–1640 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), ISBN 033363358X, p. 147.

- Andrew D. M. Barrell, Medieval Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), ISBN 052158602X, pp. 244–5.

- Andrew D. M. Barrell, Medieval Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), ISBN 052158602X, p. 257.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 68–72.

- B. Webster, Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity (St. Martin's Press, 1997), ISBN 0-333-56761-7, pp. 124–5.

- E. Ewen, "The early modern family" in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0199563691, p. 273.

- E. Ewen, "The early modern family" in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0199563691, p. 274.

- E. Ewen, "The early modern family" in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0199563691, p. 271.

- J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748614559, pp. 62–3.

- E. Ewen, "An Urban Community: The Crafts in Thirteenth Century Aberdeen" in A. Grant and K. J. Stringer, Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community: Essays Presented to G.W.S Barrow (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), p. 164.

- E. Ewen, "An Urban Community: The Crafts in Thirteenth Century Aberdeen" in A. Grant and K. J. Stringer, Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community: Essays Presented to G. W. S. Barrow (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), p. 171.

- M. A. Hall, "Women only? Women in Medieval Perth", in S. Boardman and E. Williamson, The Cult of Saints and the Virgin Mary in Medieval Scotland (London: Boydell & Brewer, 2010), ISBN 1843835622, p. 110.

- J. E. Burton, Monastic and religious orders in Britain: 1000–1300 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), ISBN 0521377978, p. 86.

- G. W. S. Barrow, Kingship and Unity: Scotland 1000–1306 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1981), ISBN 074860104X, p. 80.

- M. A. Hall, "Women only? Women in Medieval Perth", in S. Boardman and E. Williamson, The Cult of Saints and the Virgin Mary in Medieval Scotland (London: Boydell & Brewer, 2010), ISBN 1843835622, p. 109.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (Random House, 2011), ISBN 1-4464-7-563-8, pp. 104–7.

- E. Ewen, "'Hamperit in ane holy came': sights, smells and sounds in the Medieval town", in E. J. Cowan and L. Henderson, eds, A History of Everyday Life in Medieval Scotland: 1000 to 1600 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011), ISBN 0748621571, p. 126.

- E. J. Cowan and L. Henderson, "Introduction: everyday life in Scotland", in E. J. Cowan and L. Henderson, eds, A History of Everyday Life in Medieval Scotland: 1000 to 1600 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011), ISBN 0748621571, p. 6.

- E. Ewen, "The early modern family" in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0199563691, p. 278.

- A. Cathcart, Kinship and Clientage: Highland Clanship, 1451–1609 (Brill, 2006), ISBN 9004150455, pp. 81–2.

- E. Ewen, "An urban community: the crafts in thirteenth-century Aberdeen", in A. Grant and K. K. J. Stringer, eds, Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), ISBN 074861110X, p. 157.

- I. D. Whyte, "Population mobility in early modern Scotland", in R. A. Houston and I. D. Whyte, Scottish Society, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0521891671, p. 52.

- E. Ewen, "The early modern family" in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0199563691, p. 277.