Scottish society in the early modern era

Scottish society in the early modern era encompasses the social structure and relations that existed in Scotland between the early sixteenth century and the mid-eighteenth century. It roughly corresponds to the early modern era in Europe, beginning with the Renaissance and Reformation and ending with the last Jacobite risings and the beginnings of the industrial revolution.

Scotland in this period was a hierarchical society, with a complex series of ranks and orders. This was headed by the monarch and the great magnates. Below them were the lairds, who emerged as a distinct group at the top of local society was whose position was consolidated by economic and administrative change. Below the lairds in rural society were a variety of groups, often ill-defined, including yeomen, who were often major landholders, and the husbandmen, who were landholders, followed by cottars and grassmen, who often had only limited rights to common land and pasture. Urban society was led by wealthy merchants, who were often burgesses. Beneath them, and often in conflict with the urban elite, were the craftsmen. Beneath these ranks, in both urban and rural society, there were a variety of groups of mobile "masterless men", the unemployed and vagrants.

Kinship was agnatic, with descent counted only through the male line, helping to build the importance of surnames and clans. The increased power of the state and economic change eroded the power of these organisations, and this process would accelerate as the government responded to the threat of Jacobite risings by undermining the power of clan chiefs in the eighteenth century. The Reformation had a major impact on family life, changing the nature of baptism, marriage and burials, leading to a change in wider relationships, sacramental status and burial practices and placing a greater emphasis on the role of the father.

Limited demographic evidence indicates a generally expanding population, limited by short-term subsistence crises, of which the most severe was probably that of the "seven ill years" of the 1690s. The urban centres of the burghs continued to grow, with the largest being Edinburgh, followed by Glasgow. Population growth and economic dislocation from the second half of the sixteenth century led to a growing problem of vagrancy, which was responded to by a series of Acts of Parliament that established what would become the "Old Poor Law", which attempted to ensure relief for the "deserving" local poor, but punishments for the mobile unemployed and beggars. The patriarchal nature of society meant that women were directed to be subservient to their husbands and families. They remained an important part of the workforce and some were economically independent, while others lived a marginal existence. At the beginning of the period women had little or no legal status, but were increasingly criminalised after the Reformation, and were the major subjects of the witch hunts that occurred in relatively large numbers until the end of the seventeenth century.

Social structure

Aristocracy

Early modern Scotland was a hierarchical society, with a series of ranks and marks of status. Below the king were the great magnates, who by this period were no longer a feudal nobility, whose power was based on territorial landholding, but an honorific peerage, and land had become a commodity to be traded.[1] They were headed by a small number of dukes (usually descended from very close relatives of the king) and a larger group of earls. These senior nobles formed the political classes at the beginning of the period: sometimes holding major office, holding a place on the king's council and taking part in the major crises and rebellions of the period.[2] They considered themselves the king's "natural councillors" and were also the heads of a system of local patronage and loyalty. This was often formalised through bonds of manrent that set out mutual obligations and allegiances.[3]

Under the magnates were the barons, who held increasingly nominal feudal tenures of which an important vestige was the right to hold baronial courts,[3] which could deal with both matters of land ownership and interpersonal offences, including minor acts of violence.[4] Also important were the local tenants-in-chief, who held legally held their land directly from the king and who by this period were often the major local landholders in an area. In this period, as feudal distinctions declined, the barons and tenants-in-chief merged to form a new identifiable group, the lairds.[5] This group was roughly equivalent to the English gentlemen.[6] Just as the magnates saw themselves as the king's natural counsellors, so the lairds advised and exerted influence over the dukes and earls. The lairds were often the most important individual in a local community. They ran baronial courts, acted as sheriffs-depute, sat on local assizes and were called in as private arbitrators. In the course of the sixteenth century they would acquire a role in national politics, gaining representation in Parliament and playing a major role in the Reformation crisis of 1560.[3] As a result of the Reformation and the creation of a Presbyterian Kirk, their position in local society was enhanced. They often gained the new status of elder and greater oversight of the behaviour of the local population through the disciplinary functions of kirk sessions.[7]

Middle ranks

Below the lairds were a variety of groups, often ill-defined. These included yeomen, later characterised by Walter Scott as "bonnet lairds", often owning substantial land.[8] The practice of feuing (by which a tenant paid an entry sum and an annual feu duty, but could pass the land on to their heirs) meant that the number of people holding heritable possession of lands, which had previously been controlled by the church or nobility, expanded.[9] These and the lairds probably numbered about 10,000 by the seventeenth century[8] and became what the government defined as heritors, on whom the financial and legal burdens of local government increasingly fell.[10]

Below the substantial landholders were those engaged in subsistence agriculture, who made up the majority of the working population.[11] Those with property rights included husbandmen, lesser landholders and free tenants.[12] Most farming was based on the lowland fermtoun or highland baile, settlements of a handful of families that held individual land rights, but jointly farmed an area notionally suitable for two or three plough teams.[13] Below them were the cottars, who often shared rights to common pasture, occupied small portions of land and participated in joint farming as hired labour. Farms also might have grassmen, who had rights only to grazing. Eighteenth-century evidence suggests that the children of cottars and grassmen often became servants in agriculture or handicrafts.[12] Serfdom had died out in Scotland in the fourteenth century, but was virtually restored by statute law for miners and saltworkers.[8]

Society in the urban settlements of the burghs was headed by wealthier merchants, who often held local office as a burgess, alderman, bailies, or as a member of the burgh council.[14] Below them were craftsmen and workers that made up the majority of the urban population.[15] Both merchants and craftsmen often served a long apprenticeship, acquiring skills and status, before they became freemen of a burgh, and could enjoy certain rights and privileges. Major sources of trade included the export of wool, fish, coal, salt and cattle. Imports included wine, sugar and other luxury goods. Important crafts included metal working, carpentry, leather working, pottery and later brewing and wig-making.[16] There were frequent disputes between the burgesses and craftsmen over rights and political control of the burgh, occasionally bursting into violence, as occurred at Perth in the first half of the sixteenth century.[17]

The poor

At the bottom of society were the "masterless men" and women (who lacked a clear social relationship with a social superior, such as service or apprenticeship) the unemployed and vagrants, whose numbers were swelled in times of economic downturn or hardship.[18] Masterless women may have made up as much as 18 per cent of all households and particularly worried authorities.[19] In rural society those that needed relief from extreme hardship tended from the lowest ranks of rural society, including cottars, labourers and servants. Most of those who took to the roads, around three quarters, were men. Most had a disability such as blindness, or claimed to have suffered a personal disaster such as fire or theft. Some were discharged soldiers and sailors, probably returning home or searching for work. Most tended to move around a restricted area, probably moving between a limited number of parishes in search of work and relief. For some this may have been tied to the agricultural calendar, and individuals may have moved in a circuit as different foodstuffs and work became available.[20] Poor relief was more abundant in urban centres, particularly in the largest centres like Edinburgh. As a result, particularly in times of extreme hardship the poor would gravitate to the burghs. They could form a large section of society, with roughly a quarter of population of Perth in 1584 being classified as poor. The poor in urban society were a diverse group, the largest numbers women and most of those were widows. In Aberdeen in the period 1695–1705 three-quarters of the poor who received relief were women and of those two thirds were widows. The remainder were made up of servants, casual labourers, journeymen artisans, beggars, vagrants and orphans.[21]

Kinship and clans

%252C_1668_-_1700._Son_of_1st_Marquess_of_Atholl_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

Unlike in England, where kinship was predominately cognatic, derived through both males and females, in Scotland kinship was agnatic, with members of a group sharing a (sometimes fictional) common ancestor. Women retained their original surname at marriage and marriages were intended to create friendship between kin groups, rather than a new bond of kinship.[22] In the Borders this was often reflected in a common surname. A shared surname has been seen as a "test of kinship", proving large bodies of kin who could call on each other's support. At the beginning of the period this may have helped intensify the idea of the feud, which was usually carried out as a form of revenge for a kinsman, and for which a large body of kin could be counted on to support rival sides, although conflict within kin groups also occurred.[23] From the reign of James VI, systems of judicial law were enforced, and by the early eighteenth century the feud had been suppressed.[24] In the Borders, the leadership of the heads of the great surnames was largely replaced by the authority of landholding lairds in the seventeenth century.[25]

The combination of agnatic kinship and a feudal system of obligation has been seen as creating the highland clan system.[26] The head of a clan was usually the eldest son of the last chief of the most powerful sept or branch.[27] The leading families of a clan formed the fine, often seen as equivalent to lowland lairds, providing council in peace and leadership in war;[28] below them were the daoine usisle (in Gaelic) or tacksmen (in Scots), who managed the clan lands and collected the rents.[29] In the isles and along the adjacent western seaboard there were also buannachann, who acted as a military elite, defending the clan lands from raids or taking part in attacks on clan enemies. Most of the followers of the clan were tenants, who supplied labour to the clan heads and sometimes acted as soldiers. In the early modern era they usually took the clan name as their surname, turning it into a massive, if often fictive, kin group.[27] Because the Highland Clans were not a direct threat to the Restoration government, or relations with England, the same effort was not put into suppressing their independence as had been focused on the Borders, until after the Glorious Revolution.[30] Economic change and the imposition of royal justice had begun to undermine the clan system before the eighteenth century, but the process was accelerated after the rebellion of 1745, with Highland dress banned, the enforced disarming of clansmen, the compulsory purchase of heritable jurisdictions, the exile of many chiefs, and the sending of ordinary clansmen to the colonies as indentured labour. All of this largely reduced clan leaders to the status of simple landholders within one generation.[31]

Family

There was considerable concern over the safety of children in this period, prompted by high infant mortality. The abolition of godparents in the Reformation meant that baptism became a mechanism for emphasising the role and responsibilities of fathers.[32] Wet-nurses were used for young children, but in most families mothers took the primary role in bringing up children, while the Kirk emphasised the role of the father for older children.[33] After the Reformation there was an increasing emphasis on education, resulting in the growth of a parish school system, but its effects were limited for the children of the poor and for girls.[34] Most children left home for a period of life-cycle service, in which youths left home to be domestic or agricultural servants, or to become apprentices, and which ended when they married and established independent households.[35]

Marriages were often the subject of careful negotiation, particularly higher in society.[36] Marriage lost its sacramental status at the Reformation, and irregular marriage, a simple public promise or mutual agreement, followed by consummation, or cohabitation, continued to be accepted as valid throughout the period.[37][38] Women managed the household and sometimes worked beside their husbands,[35] and although obedience to husbands was stressed, this may have been limited in practice.[39] Divorce developed after the Reformation, and was available for a wider range of causes and accessed by a much larger section of society than in England.[40] Because of high mortality rates, widowhood was a relatively common state, and some women acquired independence and status, but others were forced into a marginal existence; remarriage was common.[41] The elaborate funerals and complex system of prayers for the dead that dominated in late Medieval Scotland were removed at the Reformation, when simpler services were introduced.[42][43] Burial inside the church was discouraged, causing some consternation among local lairds who wished to be buried with their ancestors. This led to the uniquely Scottish solution of adding a fourth aisle to "T"-plan churches, usually behind the pulpit, which were closed off and used for the burial of the families of the local laird. For the majority, however, burial had to be outside the church, and graveyards with stone markers became increasingly common from the early seventeenth century.[44][45]

Demography

_by_Wenceslas_Hollar_(1670).jpg.webp)

There are almost no reliable sources with which to track the population of Scotland before the late seventeenth century. Estimates based on English records suggest that by the end of the Middle Ages, the Black Death and subsequent recurring outbreaks of the plague, may have caused the population of Scotland to fall as low as half a million people.[46] Price inflation, which generally reflects growing demand for food, suggests that this probably expanded in the first half of the sixteenth century.[47] Almost half the years in the second half of the sixteenth century saw local or national scarcity, necessitating the shipping of large quantities of grain from the Baltic. Distress was exacerbated by outbreaks of plague, with major epidemics in the periods 1584–8, 1595 and 1597–1609.[48]

The population expansion probably levelled off after the famine of the 1590s, as prices were relatively stable in the early seventeenth century.[47] In the early seventeenth century famine was common, with four periods of famine prices between 1620 and 1625. The invasions of the 1640s had a profound impact on the Scottish economy, with the destruction of crops and the disruption of markets resulting in some of the most rapid price rises of the century, but population probably expanded in the period of stability that followed the Restoration in 1660.[49] Calculations based on Hearth Tax returns for 1691 indicate a population of 1,234,575. The population may have been seriously affected by the failed harvests (1695, 1696 and 1698-9) known as the "seven ill years".[50] The result was severe famine and depopulation, particularly in the north.[51] The famines of the 1690s were seen as particularly severe, partly because famine had become relatively rare in the second half of the seventeenth century, with only one year of dearth (in 1674), and the shortages of the 1690s were the last of their kind.[52] The first reliable information on national population is from the census conducted by the Reverend Alexander Webster in 1755, which showed the inhabitants of Scotland as 1,265,380 persons.[53][54]

Compared with the situation after the redistribution of population as a result of the clearances and the industrial revolution that began in the eighteenth century, these numbers must have been evenly spread over the kingdom, with roughly half living north of the Tay.[55] Most of the early modern population, in both the Lowlands and Highlands, was housed in small hamlets and isolated dwellings.[56] As the population expanded, some of these settlements were sub-divided to create new hamlets and more marginal land was settled, with sheilings (clusters of huts occupied while summer pasture was being used for grazing), becoming permanent settlements.[57] Perhaps ten per cent of the population lived in one of many burghs that had grown up in the later Medieval period, mainly in the east and south of the country. It has been suggested that they had a mean population of about 2,000, but many were much smaller than 1,000, and the largest, Edinburgh, probably had a population of over 10,000 at the beginning of the era.[58] During the seventeenth century the number of people living in the capital grew rapidly. It also expanded beyond the city walls in suburbs at Cowgate, Bristo and Westport[59] and by 1750, with its suburbs, it had reached a population of 57,000. The only other towns above 10,000 by the end of the period were Glasgow with 32,000, Aberdeen with around 16,000 and Dundee with 12,000.[60]

Poverty and vagrancy

In the Middle Ages Scotland had much more limited organisation for poor relief than England, lacking the religious confraternities of the major English cities. It possessed a few hospitals, bede houses and leper houses, which offered confinement rather than treatment.[61] Because so many Scottish parishes had been impropriated for some religious foundation, perhaps as many as 87 per cent, funds were not available for local causes such as poor relief.[62] Protestant reformers in the Book of Discipline (1560) proposed that part of the patrimony of the Catholic Church be used to support the poor, but this aim was never realised.[63] Population growth and economic dislocation from the second half of the sixteenth century led to a growing problem of vagrancy. The government reacted with three major pieces of legislation on poverty and vagrancy in 1574, 1579 and 1592. The kirk became a major element of the system of poor relief, and justices of the peace were given responsibility for dealing with the issue. The 1574 poor law act was modelled on the English act passed two years earlier; it limited relief to the deserving poor of the old, sick and infirm, imposing draconian punishments on a long list of "masterful beggars", including jugglers, palmisters and unlicensed tutors. Parish deacons, elders or other overseers,[48] and in the burghs bailies and provosts,[64] were to draw up lists of deserving poor, and each would be assessed. Those not belonging to the parish were to be sent back to their place of birth and might be put in the stocks or otherwise punished, probably actually increasing the level of vagrancy. Unlike the English act, there was no attempt to provide work for the able-bodied poor.[48] In practice, the strictures on begging were often disregarded in times of extreme hardship.[65] Poor rates were very slow to be set up in the burghs, with Edinburgh the first as a result of the outbreak of plague in 1584. It was then gradually introduced in other cities, such as St Andrews in 1597, Perth in 1599, Aberdeen in 1619, and Glasgow and Dundee in 1636.[66]

This legislation provided the basis of what would later be known as the "Old Poor Law" in Scotland, which remained in place until the mid-nineteenth century, when, faced with the much greater problems of poverty caused by industrialisation and population growth, a more comprehensive system, known as the New Poor Law, was created.[67] Most subsequent legislation built on its principles of provision for the local deserving poor and punishment of mobile and undeserving "sturdie beggars". The most important later act was that of 1649, which declared that local heritors were to be assessed by kirk session to provide the financial resources for local relief, rather than relying on voluntary contributions.[68] By the mid-seventeenth century the system had largely been rolled out across the Lowlands, but was limited in the Highlands.[66] The system was largely able to cope with general poverty and minor crises, helping the old and infirm to survive and provide life support in periods of downturn at relatively low cost, but was overwhelmed in the major subsistence crisis of the 1690s.[69]

Women

Early modern Scotland was a theoretically patriarchal society, in which men had total authority over women, but how this worked is practice is difficult to discern.[36] Marriages, particularly higher in society, were often political in nature and the subject of complex negotiations over the tocher (dowry). Some mothers took a leading role in negotiating and finding marriages, as Lady Glenorchy did for her children in the 1560s and 1570s, or as matchmakers, finding suitable and compatible partners. Before the Reformation, the extensive marriage bars for kinship meant that most marriages necessitated a papal dispensation, which could later be used as grounds for annulment if the marriage proved politically or personally inconvenient.[36] At the beginning of the period, women had a very limited legal status. The criminal courts refused to recognise them as witnesses or independent criminals, and responsibly for their actions was assumed to lie with their husbands, fathers and kin. In the post-Reformation period there was a criminalisation of women, partly evident in witchcraft prosecutions from 1563.[35] Through the 1640s, independent commissions were set up to try women for child murder, and after pressure from the kirk a law of 1690 placed the presumption of guilt on a woman if she concealed a pregnancy and birth, and her child later died.[35]

By the eighteenth century many poorer girls were being taught in dame schools, informally set up by a widow or spinster to teach reading, sewing and cooking.[70] Among the nobility there were many educated and cultured women.[71] Women formed an important part of the workforce. Many unmarried women worked away from their families as farm servants, and married women worked with their husbands around the farm, taking part in all major agricultural tasks. They had a particular role as shearers in the harvest, forming most of the reaping team of the bandwin. Women also played an important part in the expanding textile industries, spinning and setting up warps for men to weave. There is evidence of single women engaging in independent economic activity, particularly for widows, who can be found keeping schools, brewing ale and trading.[35] Some were highly successful, such as Janet Fockart, an Edinburgh Wadwife or moneylender, who had been left a widow with seven children after her third husband's suicide, and who managed her business affairs so successfully that she amassed a moveable estate of £22,000 by her death in the late sixteenth century.[72] Lower down the social scale, the rolls of poor relief indicate that large numbers of widows with children endured a marginal existence.[35]

Popular religion

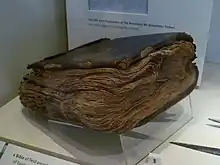

Scottish Protestantism was focused on the Bible, which was seen as infallible and the major source of moral authority. Many Bibles were large, illustrated and highly valuable objects. In the early part of the century the Genevan translation was commonly used.[73] In 1611 the Kirk adopted the Authorised King James Version and the first Scots version was printed in Scotland in 1633, but the Geneva Bible continued to be employed into the seventeenth century.[74] Bibles often became the subject of superstitions, being used in divination.[75] Family worship was strongly encouraged by the Covenanters. Books of devotion were distributed to encourage the practice and ministers were encouraged to investigate whether this was being carried out.[76] The seventeenth century marked the high-water mark of kirk discipline. Kirk sessions were able to apply religious sanctions, such as excommunication and denial of baptism, to enforce godly behaviour and obedience. In more difficult cases of immoral behaviour they could work with the local magistrate, in a system modelled on that employed in Geneva.[77]

Public occasions were treated with mistrust and from the later seventeenth century there were efforts by kirk sessions to stamp out activities such as well-dressing, bonfires, guising, penny weddings and dancing.[78] The Reformation had a severe impact on church music.[79] The Lutheranism that influenced the early Scottish Reformation attempted to accommodate Catholic musical traditions into worship, drawing on Latin hymns and vernacular songs. The most important product of this tradition in Scotland was The Gude and Godlie Ballatis, which were spiritual satires on popular ballads composed by the brothers James, John and Robert Wedderburn. Never adopted by the kirk, they nevertheless remained popular and were reprinted from the 1540s to the 1620s. Later the Calvinism that came to dominate was much more hostile to Catholic musical tradition and popular music, placing an emphasis on the Psalms. The Scottish Psalter of 1564 was commissioned by the Assembly of the Church. Whole congregations would now all sing these psalms, often using common tunes, unlike the trained choirs who had sung the many parts of polyphonic hymns.[80]

Witchtrials

From late Medieval Scotland there is evidence of occasional prosecutions of individuals for causing harm through witchcraft, but these may have been declining in the first half of the sixteenth century. In the aftermath of the initial Reformation settlement, Parliament passed the Witchcraft Act 1563, similar to that passed in England one year earlier, which made witchcraft a capital crime. Despite the fact that Scotland probably had about one quarter of the population of England, it had three times the number of witchcraft prosecutions, at about 6,000 for the entire period.[81] James VI's visit to Denmark, a country familiar with witch hunts, may have encouraged an interest in the study of witchcraft.[82] After his return to Scotland, he attended the North Berwick witch trials, the first major persecution of witches in Scotland under the 1563 Act. Several people, most notably Agnes Sampson, were convicted of using witchcraft to send storms against James' ship. James became obsessed with the threat posed by witches and, inspired by his personal involvement, in 1597 wrote the Daemonologie, a tract that opposed the practice of witchcraft and which provided background material for Shakespeare's Tragedy of Macbeth.[83] James is known to have personally supervised the torture of women accused of being witches.[83] After 1599, his views became more sceptical.[84]

In the seventeenth century the pursuit of witchcraft was largely taken over by the kirk sessions, and was often used to attack superstitious and Catholic practices in Scottish society. Most of the accused, 75 per cent, were women, with over 1,500 executed, and the witch hunt in Scotland has been seen as a means of controlling women.[85] The most intense witch hunt was in 1661–62, which involved 664 named witches in four counties.[86] From this point prosecutions began to decline, as trials were more tightly controlled by the judiciary and government, torture was more sparingly used and standards of evidence were raised. There may also have been a growing scepticism, and with relative peace and stability the economic and social tensions that contributed to accusation may have reduced. There were occasional local outbreaks such as the one in East Lothian in 1678 and Paisley in 1697. The last recorded executions were in 1706, and the last trial was in 1727. The British parliament repealed the 1563 Witchcraft Act in 1736.[87]

Notes

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, p. 28.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 12–22.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 30–3.

- R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, p. 81.

- R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, p. 79.

- A. Grant, "Service and tenure in late medieval Scotland 1324–1475" in A. Curry and E. Matthew, eds, Concepts and Patterns of Service in the Later Middle Ages (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2000), ISBN 0851158145, pp. 145–65.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, p. 138.

- R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, p. 80.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 51–2.

- J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748614559, p. 331.

- A. Grant, "Late medieval foundations", in A. Grant and K. J. Stringer, eds, Uniting the Kingdom?: the Making of British History (London: Routledge, 1995), ISBN 0415130417, p. 99.

- R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, p. 82.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 41–55.

- K. Stevenson, "Thai war callit knynchtis and bere the name and the honour of that hye ordre: Scottish knighthood in the fifteenth century", in L. Clark, ed., Identity and Insurgency in the Late Middle Ages (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2006), ISBN 1843832704, p. 38.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 48–9.

- R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, pp. 100–3.

- M. Verschuur, "Merchants and craftsmen in sixteenth-century Perth", in M. Lynch, ed., The Early Modern Town in Scotland (London: Taylor & Francis, 1987), ISBN 0709916779, p. 39.

- J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748614559, p. 286.

- M. Lynch, "Preaching to the converted?: perspectives on the Scottish Reformation", in A. Alasdair A. MacDonald, M. Lynch and I. B. Cowan, The Renaissance in Scotland: Studies in Literature, Religion, History, and Culture Offered to John Durkhan (BRILL, 1994), ISBN 9004100970, p. 340.

- I. D. Whyte, "Population mobility in early modern Scotland", in R. A. Houston and I. D. Whyte, eds, Scottish Society, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0521891671, pp. 55–7.

- R. A. Houston and I. D. Whyte, "Introduction" in R. A. Houston and I. D. Whyte, eds, Scottish Society, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0521891671, p. 13.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 29–35.

- J. W. Armstrong, "The 'fyre of ire Kyndild' in the fifteenth-century Scottish Marches", in S. A. Throop and P. R. Hyams, eds, Vengeance in the Middle Ages: Emotion, Religion and Feud (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2010), ISBN 075466421X, p. 71.

- R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, pp. 15–16.

- R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, p. 92.

- G. W. S. Barrow, Robert Bruce (Berkeley CA.: University of California Press, 1965), p. 7.

- J. L. Roberts, Clan, King, and Covenant: History of the Highland Clans from the Civil War to the Glencoe Massacre (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2000), ISBN 0748613935, p. 13.

- M. J. Green, The Celtic World (London: Routledge, 1996), ISBN 0415146275, pp. 667.

- D. Moody, Scottish Family History (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Com, 1994), ISBN 0806312688, pp. 99–104.

- R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, p. 122.

- R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, pp. 166–7.

- M. Hollander, "The name of the Father": baptism and the social construction of fatherhood in early modern Edinburgh", in E. Ewan and J. Nugent, Finding the Family in Medieval and Early Modern Scotland (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008), ISBN 0754660494, p. 68.

- E. Ewen, "The early modern family" in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0199563691, p. 278.

- R. A. Houston, Scottish Literacy and the Scottish Identity: Illiteracy and Society in Scotland and Northern England, 1600–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), ISBN 0-521-89088-8, pp. 5 and 63-8.

- R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, pp. 86–8.

- J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748614559, pp. 62–3.

- E. Ewen, "The early modern family" in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0199563691, p. 270.

- J. R. Gillis, For Better, For Worse, British marriages, 1600 to the Present (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), p. 195.

- E. Ewen, "The early modern family" in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0199563691, p. 274.

- E. Ewen, "The early modern family" in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0199563691, p. 273.

- D. G. Mullan, "Parents and children in early modern Scotland", in E. Ewan and J. Nugent, Finding the Family in Medieval and Early Modern Scotland (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008), ISBN 0754660494, p. 75.

- J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748614559, p. 33.

- Andrew D. M. Barrell, Medieval Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), ISBN 052158602X, p. 254.

- E. Ewen, "The early modern family" in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0199563691, p. 275.

- J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748614559, p. 131.

- S. H. Rigby, ed., A Companion to Britain in the Later Middle Ages (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2003), ISBN 0631217851, pp. 109–11.

- R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0415278805, p. 145.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 166–8.

- R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0415278805, pp. 291–3.

- R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0415278805, pp. 291–2 and 301-2.

- K. J. Cullen, Famine in Scotland: The “Ill Years” of the 1690s (Edinburgh University Press, 2010), ISBN 0748638873.

- R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0415278805, pp. 254–5.

- K. J. Cullen, Famine in Scotland: The 'Ill Years' of The 1690s (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010), ISBN 0748638873, pp. 123–4.

- Team, National Records of Scotland Web (2013-05-31). "National Records of Scotland". National Records of Scotland. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, p. 61.

- I. D. Whyte and K. A. Whyte, The Changing Scottish Landscape: 1500–1800 (London: Taylor & Francis, 1991), ISBN 0415029929, p. 5.

- I. D. Whyte and K. A. Whyte, The Changing Scottish Landscape: 1500–1800 (London: Taylor & Francis, 1991), ISBN 0415029929, pp. 18–19.

- E. Gemmill and N. J. Mayhew, Changing Values in Medieval Scotland: a Study of Prices, Money, and Weights and Measures (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), ISBN 0521473853, pp. 8–10.

- W. Makey, "Edinburgh in mid-seventeenth century", in M. Lynch, ed., The Early Modern Town in Scotland (London: Taylor & Francis, 1987), ISBN 0709916779, pp. 195–6.

- F. M. L. Thompson, The Cambridge Social History of Britain 1750–1950: People and Their Environment (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), ISBN 0521438152, p. 5.

- O. P. Grell and A. Cunningham, Health Care and Poor Relief in Protestant Europe, 1500–1700 (London: Routledge, 1997), ISBN 0415121302, p. 223.

- O. P. Grell and A. Cunningham, Health Care and Poor Relief in Protestant Europe, 1500–1700 (London: Routledge, 1997), ISBN 0415121302, p. 230.

- O. P. Grell and A. Cunningham, Health Care and Poor Relief in Protestant Europe, 1500–1700 (London: Routledge, 1997), ISBN 0415121302, p. 36.

- O. P. Grell and A. Cunningham, Health Care and Poor Relief in Protestant Europe, 1500–1700 (London: Routledge, 1997), ISBN 0415121302, p. 221.

- R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, p. 143.

- O. P. Grell and A. Cunningham, Health Care and Poor Relief in Protestant Europe, 1500–1700 (London: Routledge, 1997), , ISBN 0415121302, p. 37.

- R. Mitchison, The Old Poor Law in Scotland: the Experience of Poverty, 1574–1845 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2000), ISBN 0748613447.

- R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0415278805, p. 96.

- R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X, pp. 127 and 145.

- B. Gatherer, "Scottish teachers", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, Scottish Education: Post-Devolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1625-X, p. 1022.

- K. Brown, Noble Society in Scotland: Wealth, Family and Culture from Reformation to Revolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), ISBN 0748612998, p. 187.

- J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748614559, p. 322.

- G. D. Henderson, Religious Life in Seventeenth-Century Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), ISBN 0521248779, pp. 1–4.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 192–3.

- G. D. Henderson, Religious Life in Seventeenth-Century Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), ISBN 0521248779, p. 12.

- G. D. Henderson, Religious Life in Seventeenth-Century Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), ISBN 0521248779, p. 8.

- R. A. Houston, I. D. Whyte "Introduction" in R. A. Houston, I. D. Whyte, eds, Scottish Society, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0521891671, p. 30.

- R. A. Houston, I. D. Whyte "Introduction" in R. A. Houston, I. D. Whyte, eds, Scottish Society, 1500–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), ISBN 0521891671, p. 34.

- A. Thomas, "The Renaissance", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0191624330, pp. 198–9.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 187–90.

- K. A. Edwards, "Witchcraft in Tudor and Stuart Scotland", in K. Cartwright, A Companion to Tudor Literature Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture (Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2010), ISBN 1405154772, p. 32.

- P. Croft, King James (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), ISBN 0-333-61395-3, p. 26.

- J. Keay and J. Keay, Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland (London: Harper Collins, 1994), ISBN 0-00-255082-2, p. 556.

- P. Croft, King James (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), ISBN 0-333-61395-3, p. 27.

- S. J. Brown, "Religion and society to c. 1900", T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, eds, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0199563691, p. 81.

- B. P. Levak, "The decline and end of Scottish witch-hunting", in J. Goodare, ed., The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), ISBN 0719060249, p. 169.

- B. P. Levak, "The decline and end of Scottish witch-hunting", in J. Goodare, ed., The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), ISBN 0719060249, pp. 166–180.

Bibliography

- O. P. Grell and A. Cunningham, Health Care and Poor Relief in Protestant Europe, 1500–1700 (London: Routledge, 1997), ISBN 0415121302

- R. Mitchison, Lordship to Patronage, Scotland 1603–1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1983), ISBN 074860233X

- R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0415278805

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763