Society of Polish Artists "Sztuka"

The Society of Polish Artists "Sztuka" (Polish: Towarzystwo Artystów Polskich "Sztuka"; Sztuka means Art in Polish, artyzm means artistic abilities) founded in 1897 in Kraków, was a gathering of prominent Polish visual artists from around the turn of the century (or fin-de-siècle era) living under the foreign partitions of Poland. Its main goal was to reaffirm the importance and unique character of Polish contemporary art at a time, when Poland could not exist as sovereign nation.[1]

.jpg.webp) | |

| Formation | October 27, 1897 |

|---|---|

| Dissolved | 1950 |

| Type | Association |

| Headquarters | Kraków |

Region served | Poland |

| Leader | Jan Stanisławski (followed by) |

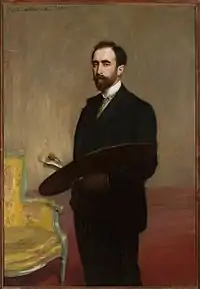

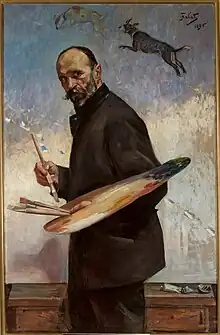

The immediate inspiration for the founding of the new society came from the ground-breaking art exhibit inaugurated on May 27, 1897 at Sukiennice in Main Square, Kraków.[2] It was held by Polish modernist painters,[2] and called A Separate Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture (Wystawa osobna obrazów i rzeźb).[3] The show was visited by approximately 6,000 guests, and proclaimed a success. The first meeting of Sztuka Society took place on October 27, 1897.[4] Among its founding members were a generation of academics from the School of Fine Arts who also participated in the show, including future Rectors of the Academy: Leon Wyczółkowski, Teodor Axentowicz, Jacek Malczewski, Józef Mehoffer; as well as artists Józef Chełmoński, Julian Fałat, Antoni Piotrowski, Jan Stanisławski, Włodzimierz Tetmajer and Stanisław Wyspiański.[2]

Principles

Sztuka's artistic philosophy was by no means homogeneous – encompassing all facets of the Young Poland movement including neo-romanticism, symbolism, impressionism and art nouveau. Sculpture was represented in Sztuka by Xawery Dunikowski, Bolesław Biegas, Konstanty Laszczka, and Wacław Szymanowski. It was "a happy hour" for Polish modernists, wrote historian Maria Poprzecka, because the prevailing trends in European art of the time (Edvard Munch, August Strindberg) were perfectly aligned with extreme pessimism of the Poles under the foreign rule.[1]

The membership of the society was tightly controlled in order to protect its identity. It was especially important considering that the Polish artists were forced to exhibit abroad under the banner of Poland's own occupiers. For example, when the 1892 Munich International Exhibition of Fine Arts chose to create a Polish department, the Tsarist official from the Russian-controlled Warsaw named it a political provocation in his official protest. As a result, at the 1900 World Exposision Poles from the Russian sector of occupied Poland were allowed to exhibit only with the Russians from Russia.[5]

Sztuka Society survived two world wars. With time, many other prominent artists joined in such as Olga Boznańska and Józef Pankiewicz. Its role began to diminish in the interwar period. The society was also criticized for being too exclusive and accused of having nationalistic ideals. However, it was discontinued only under the Stalinist system, in 1950.[6]

Notes and references

- Professor Irena Kossowska, Polish Academy of Sciences (Autumn 2002). "Review of Out Looking In: Early Modern Polish Art, 1890–1918 by Jan Cavanaugh, University of California Press, 2000" (Volume 1, Issue 2). A Journal of Nineteenth-Century Visual Culture. Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- Anna Brzyski (2007). Making Art in the Age of Art History (Google books preview). pp. 257–266. ISBN 978-0822340850. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Stefania Krzysztofowicz-Kozakowska (2006). "Sztuka, Wiener Secession, Mánes: The Central European Art Triangle". Artibus et Historiae. 27 (53): 217–259. doi:10.2307/20067117. JSTOR 20067117.

- Anna Brzyski, transl. (1899). "Report of the Committee of the Association of Polish Artists "Sztuka" for the year 1898" (PDF file, direct download, 79.9 KB). Warsaw: Tygodnik Ilustrowany. p. 379. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- Michelle Facos (2011). Individualism and collectivism. pp. 396–397. ISBN 978-1136840715. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Marek Bartelik (2005). A real and mythological place (Google books preview). pp. 33 (#20). ISBN 0719063523. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

- Anna Brzyski (2007). "Charter & Bylaws. Minutes of Meetings (1897-1912)". Association of Polish Artists 'Sztuka' / Towarzystwo Artystow Polskich ' Sztuka'. Art Worlds.org. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

.jpg.webp)