Socorro, New Mexico

Socorro (/səˈkɔːroʊ/, sə-KOR-oh) is a city in Socorro County in the U.S. state of New Mexico. It is in the Rio Grande Valley at an elevation of 4,579 feet (1,396 m). In 2010 the population was 9,051. It is the county seat of Socorro County.[4] Socorro is located 74 miles (119 km) south of Albuquerque and 146 miles (235 km) north of Las Cruces.

Socorro, New Mexico | |

|---|---|

Socorro aerial view | |

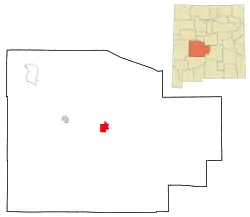

Location of Socorro in Socorro County, New Mexico | |

Socorro, New Mexico Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 34°3′42″N 106°53′58″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New Mexico |

| County | Socorro |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ravi Bhasker[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 14.46 sq mi (37.46 km2) |

| • Land | 14.45 sq mi (37.43 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.03 km2) |

| Elevation | 4,603 ft (1,403 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 8,707 |

| • Density | 602.39/sq mi (232.59/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−07:00 (Mountain (MST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−06:00 (MDT) |

| ZIP Code | 87801 |

| Area code | 575 |

| FIPS code | 35-73540 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0938832 |

| Website | www |

History

Founding

In June 1598, Juan de Oñate led a group of Spanish settlers through the Jornada del Muerto, an inhospitable patch of desert that ends just south of the present-day city of Socorro. As the Spaniards emerged from the desert, Piro Indians of the pueblo of Teypana gave them food and water. Therefore, the Spaniards renamed this pueblo Socorro, which means "help" or "aid". Later, the name "Socorro" would be applied to the nearby Piro pueblo of Pilabó.[5]

Nuestra Señora de Perpetuo Socorro, the first Catholic mission in the area, was probably established c. 1626. Fray Agustín de Vetancurt would later write that around 600 people lived in the area during this period.[6] Mines in the Socorro mountains were opened by 1626.[7]

During the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, Spanish refugees stopped in the pueblo of Socorro. A number of Piro Indians followed the Spaniards as they left the province to go south to safety. With no protection of Spanish troops, Socorro was destroyed and the remaining Piro were killed by the Apache and other tribes.[8]

The Spanish did not initially resettle Socorro when they re-conquered New Mexico. Other than El Paso, there were no Spanish settlements south of Sabinal (which is approximately 30 miles (48 km) north of Socorro) until the 1800s.[9] In 1800, governor Fernando Chacon gave the order to resettle Socorro and other villages in the area. However, Socorro was not resettled until about 1815.[10] In 1817, 70 Belen residents petitioned the crown for land in Socorro.[11] The 1833 Socorro census lists over 400 residents, with a total of 1,774 people living within the vicinity of the village.[12]

The mission of San Miguel de Socorro was established soon after Socorro was resettled. The church was built on the ruins of the old Nuestra Señora de Socorro.[13]

Territorial period

_(14779554781).jpg.webp)

In August 1846, during the Mexican–American War, New Mexico was occupied by the American Army. In Las Vegas, New Mexico, Colonel Stephen W. Kearny proclaimed New Mexico's independence from Mexico. On their way to begin their assault on Mexico, American troops stopped in Socorro. A British officer, Lt. George Ruxton, commented that these soldiers were "unwashed and unshaven, were ragged and dirty, without uniforms..." and were lacking in discipline.[14]

In September 1850, New Mexico became a territory of the United States. At the time, New Mexico encompassed what is now the states of New Mexico and Arizona. In 1850, the population of Socorro was only 543 people. This included 100 American soldiers who were soon moved to Valverde.[15]

The first military post built near Socorro was Fort Conrad, 30 miles (48 km) south of the town. Built in August 1851, the fort was badly constructed and was abandoned for Fort Craig, located a few miles away. Fort Craig was first occupied on March 31, 1854.[16][17]

The New Mexico School of Mines (now the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology) was founded in Socorro in 1889.

On April 24, 1964, Lonnie Zamora, a local policeman, claimed to have observed a flying saucer and two little beings. Zamora's claim is known as the Lonnie Zamora incident.

Geography and geology

Socorro is located 75 miles (121 km) south of Albuquerque, at an average elevation of 4,605 feet (1,404 m). The town lies adjacent to the Rio Grande in a landscape dominated by the Rio Grande rift and numerous extinct volcanoes. The immediate region encompasses approximately 6,000 feet (1,800 m) of vertical relief between the Rio Grande and the Magdalena Mountains. Notable nearby locales include the Cibola National Forest, the Bureau of Land Management Quebradas Scenic Backcountry Byway, and the Bosque del Apache and Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuges. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 14.4 square miles (37 km2), of which 0.04 square miles (0.10 km2), or 0.21%, is water.

Climate

Socorro has a cold semi-arid climate (BSk). Summers are hot, reaching 90 °F (32 °C) on an average of 82 days annually. Winters are mild, but nights are cold with 126 days falling to or below freezing per year. The record high temperature of 109 °F (43 °C) was recorded on June 26, 1994, while the record low of −16 °F (−27 °C) was recorded on December 21, 1909.

Socorro averages 10.05 inches (255 mm) of annual precipitation, with a peak of 2.43 inches (62 mm) in July.

| Climate data for Socorro, New Mexico, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 76 (24) |

82 (28) |

91 (33) |

95 (35) |

102 (39) |

109 (43) |

108 (42) |

106 (41) |

102 (39) |

95 (35) |

86 (30) |

81 (27) |

109 (43) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 65.4 (18.6) |

72.3 (22.4) |

81.3 (27.4) |

87.0 (30.6) |

93.8 (34.3) |

100.5 (38.1) |

100.9 (38.3) |

97.7 (36.5) |

93.4 (34.1) |

85.7 (29.8) |

75.0 (23.9) |

66.2 (19.0) |

101.4 (38.6) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 52.2 (11.2) |

59.2 (15.1) |

67.4 (19.7) |

74.7 (23.7) |

82.7 (28.2) |

91.2 (32.9) |

91.5 (33.1) |

88.9 (31.6) |

83.6 (28.7) |

72.7 (22.6) |

60.5 (15.8) |

50.5 (10.3) |

72.9 (22.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 37.8 (3.2) |

43.6 (6.4) |

50.5 (10.3) |

57.7 (14.3) |

65.8 (18.8) |

74.1 (23.4) |

77.4 (25.2) |

75.1 (23.9) |

68.5 (20.3) |

57.1 (13.9) |

45.5 (7.5) |

37.1 (2.8) |

57.5 (14.2) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 23.3 (−4.8) |

27.9 (−2.3) |

33.7 (0.9) |

40.8 (4.9) |

49.0 (9.4) |

57.1 (13.9) |

63.3 (17.4) |

61.2 (16.2) |

53.4 (11.9) |

41.5 (5.3) |

30.5 (−0.8) |

23.7 (−4.6) |

42.1 (5.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 11.3 (−11.5) |

14.6 (−9.7) |

18.8 (−7.3) |

27.5 (−2.5) |

35.2 (1.8) |

45.0 (7.2) |

54.8 (12.7) |

52.8 (11.6) |

40.5 (4.7) |

26.7 (−2.9) |

16.2 (−8.8) |

10.3 (−12.1) |

8.2 (−13.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −12 (−24) |

−2 (−19) |

0 (−18) |

15 (−9) |

23 (−5) |

35 (2) |

42 (6) |

37 (3) |

27 (−3) |

14 (−10) |

−13 (−25) |

−16 (−27) |

−16 (−27) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.30 (7.6) |

0.28 (7.1) |

0.51 (13) |

0.34 (8.6) |

0.38 (9.7) |

0.42 (11) |

2.43 (62) |

2.09 (53) |

1.34 (34) |

0.94 (24) |

0.45 (11) |

0.57 (14) |

10.05 (255) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 8.7 | 9.2 | 6.5 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 53.7 |

| Source: NOAA[18][19] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 1,272 | — | |

| 1890 | 2,295 | 80.4% | |

| 1900 | 1,512 | −34.1% | |

| 1910 | 1,560 | 3.2% | |

| 1920 | 1,256 | −19.5% | |

| 1930 | 2,058 | 63.9% | |

| 1940 | 3,712 | 80.4% | |

| 1950 | 4,334 | 16.8% | |

| 1960 | 5,271 | 21.6% | |

| 1970 | 5,849 | 11.0% | |

| 1980 | 7,173 | 22.6% | |

| 1990 | 8,159 | 13.7% | |

| 2000 | 8,877 | 8.8% | |

| 2010 | 9,051 | 2.0% | |

| 2020 | 8,707 | −3.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[20][3] | |||

As of the census of 2000, there were 8,877 people, 3,415 households, and 2,151 families residing in the city.[21] The population density was 615.8 inhabitants per square mile (237.8/km2). There were 3,940 housing units at an average density of 273.3 per square mile (105.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 66.16% White, 0.74% African American, 2.77% Native American, 2.24% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 23.24% from other races, and 4.79% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 54.50% of the population. There were 3,415 households, out of which 31.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.5% were married couples living together, 14.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.0% were non-families. 29.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.44 and the average family size was 3.02. In the City of Socorro 25.4% of the total population was under the age of 18, 16.9% from 18 to 24, 25.7% from 25 to 44, 20.4% from 45 to 64, and 11.6% were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31 years. For every 100 females, there were 106.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $22,530, and the median income for a family was $33,013. Males had a median income of $31,517 versus $23,071 for females. The per capita income for the city was $13,250. About 24.1% of families and 32.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 44.4% of those under age 18 and 23.6% of those age 65 or over.

The languages spoken at home were 62.41% English, 35.64% Spanish, 0.90% Chinese, 0.76% German, and 0.36% Navajo.[22]

Economy

Major employers in Socorro include the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology (NM Tech), the Bureau of Land Management, Socorro General Hospital, the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, municipal and county governments, Socorro Consolidated Schools.

Golf

The Elfego Baca Golf Shoot is named after a former mayor of Socorro who survived a gun battle near what is now Reserve, New Mexico, involving over 4,000 bullets that were fired over the course of 36 hours. The golf shoot begins by teeing off from Socorro Peak, also known as M Mountain, at an altitude of 7,243 feet (2,208 m), golfers proceed down the side of the mountain some 2,550 vertical feet to the one hole almost three miles (5 km) away. Surviving rattlesnakes, gnats, cacti, treacherous terrain and the New Mexican sun and heat, golfers have a chance at winning the title to what is considered one of the two most difficult golf courses in the world.

Points of interest

Education

Socorro Consolidated School District has approx. 2,000 students and 285 staff.[23] Socorro has one public high school, Socorro High School.

The town is the location of the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, which is a state-funded research- and teaching-oriented university. New Mexico Tech has approximately 1,500 undergraduate students, 500 graduate students, and 150 academic staff.

Currently, the Summer Science Program in Astrophysics is hosted at New Mexico Tech.

Infrastructure

Airport

The Socorro airport, located on the southern edge of the city, received scheduled airline service by Continental Airlines in the early 1950s. A Douglas DC-3 aircraft provided a daily northbound flight to Albuquerque (that went on to Denver after several stops) and a southbound flight to El Paso with stops at Truth or Consequences and Las Cruces. Zia Airlines, a small commuter airline, also made on-demand flag stops at the Socorro airport on their flights between Albuquerque and Las Cruces in the mid 1970s.[24] The airport remains in use as a general aviation facility with several based aircraft.

In popular culture

Socorro was among the locations in the movie Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore (1974), though in a somewhat derogatory sense, as Ellen Burstyn's character decides to leave the town for a new beginning elsewhere. The aftermath scene of Burstyn's character's husband's fatal traffic accident at the beginning of the film, although implied as being in Socorro, was actually filmed in Tucson.

The Roger Corman movie Gas-s-s-s (1971) was filmed in and around Socorro, including a scene using the New Mexico Tech golf carts.

Actress Jodie Foster stayed in Socorro while filming the movie Contact (1997) at the Very Large Array fifty miles west of the city. Based on the map that was faxed to Jodie Foster's character (Dr. Eleanor Arroway) in the film, the Socorro airport was also the location of meeting between Dr. Arroway and S.R. Hadden.[25]

12 Strong (2018) had several scenes recorded in Socorro, NM due to how similar the terrain was to Afghanistan. Filming specifically took place on M Mountain for several days, among the Energetic Materials Research and Testing Center's bomb range. 50 extras from Socorro and surrounding areas were used in several scenes in the film. Originally titled "Horse Soldiers", filming also took place in White Sands National Monument, and Fort Bliss. During this time, production crew and actors were seen in Socorro as they mostly stayed in local hotels, and ate out at local restaurants. Chris Hemsworth was spotted at the Socorro Springs restaurant and New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology's gym.[26]

Notable people

- Elfego Baca (1865–1945), lawman, lawyer, and politician[27]

- Jeff Bhasker, record producer and musician

- Conrad Hilton (1887–1979), founder of the Hilton Hotels chain[28]

- Robert Fortune Sanchez (1938–2012), Roman Catholic archbishop

- Holm O. Bursum (1867-1953)

- Jan Thomas, (1958-) Children's writer and illustrator.

References

- "Socorro, New Mexico". City of Socorro. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- "Census Population API". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Marshal, Michael P. & Walt, Henry J., “Rio Abajo: Prehistory and History of a Rio Grande Province” (Santa Fe: New Mexico Historical Preservation Program, 1984), p 248

- Marshal & Walt, "Rio Abajo", p 248.

- Zarate Salmeron, Geronimo de (1966) Relaciones: an account of things seen and learned by Father Jeronimo de Zarati Salmeron from the year 1538 to year 1626 (translated by Alicia Ronstadt Milich) Horn & Wallace, Albuquerque, New Mexico, Section XXXIV (page 56), OCLC 221277018

- Marshal & Walt, "Rio Abajo", pp. 248–249 .

- Marshal & Walt, "Rio Abajo", p 280.

- Marshal & Walt, "Rio Abajo", p 285.

- Ramirez Alief, Teresa, et al., eds. "New Mexico Census of 1833 and 1845: Socorro and Surrounding Communities of the Rio Abajo." (Albuquerque: New Mexico Genealogical Society, Inc., 1994.) p.xiii.

- Ramirez Alief, Teresa, et al., "New Mexico Census: Socorro" pp. 2–10; 32

- Marshal & Walt, "Rio Abajo", p 249.

- Ashcroft, Bruce (1988). The Territorial History of Socorro, New Mexico. El Paso: University of Texas at El Paso. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0874041694.

- Ashcroft, "The Territorial History of Socorro", p. 6

- Marshal and Walt, "Rio Abajo", p. 273

- After the 1862 Battle of Valverde two Texas fatalities from the battle were buried in Socorro, New Mexico see Houston Genealogy listing 16 Texas fatalities from the Battle of Valverle. Likewise in a small skirmish at Socorro, a small party of four men under a Lt. Simmons CSA was surprised under Captain James "Paddy" Graydon and his spy company; one Confederate was killed [Battles and Leaders of the Civil war Vol .II .p.106 footnote].

- "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991-2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Census". United States Census Bureau. 2000. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Socorro, New Mexico". MLA. 2000. Retrieved October 21, 2007.

- "Welcome to the SCS Website". Socorro Consolidated Schools. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- Continental Airlines and Zia Airlines timetables

- Finley, Dave. "Hollywood Comes to Socorro". Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Turner, Scott. "Horse Soldiers to Wrap up Here". DCChieftain. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Boggs, Johnny D. (June 14, 2016). "Following Elfego Baca". True West Magazine. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- Turkel, Stanley (September 16, 2009). Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry. AuthorHouse. p. 127. ISBN 9781449007546.

Bibliography

- Socorro "Saucer" in a Pentagon Pantry, Ray Stanford, author. Blueapple Books, 1976.

- X Descending, Christian Lambright, author. X Desk Publishing, 2012. pp. 269–274.

- The UFO Book: Encyclopedia of the Extraterrestrial, Jerome Clark, author. Visible Ink Press, 1998. pp. 545–558.