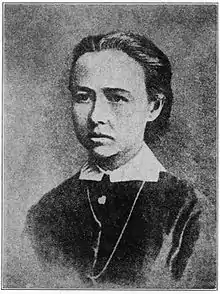

Sophia Perovskaya

Sophia Lvovna Perovskaya (Russian: Со́фья Льво́вна Перо́вская; 13 September [O.S. 1 September] 1853 – 15 April [O.S. 3 April] 1881) was a Russian revolutionary and a member of the revolutionary organization Narodnaya Volya. She helped orchestrate the assassination of Alexander II of Russia, for which she was executed by hanging.

Sophia Perovskaya | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 13 September 1853 |

| Died | 15 April 1881 (aged 27) |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Spouse | Andrei Zhelyabov |

Life as a revolutionary

Perovskaya was born in Saint Petersburg, into an aristocratic family who were the descendants by the marriage of Elizabeth of Russia. Her father, Lev Nikolaievich Perovsky, was the military governor of Saint Petersburg. Her grandfather, Nikolay Perovsky, was a governor of Taurida. She spent her early years in the Crimea, where her education was largely neglected, but where she began reading serious books on her own.[1] After the family moved to Saint Petersburg, Perovskaya entered the Alarchinsky Courses, a girls’ preparatory program.[2] Here she became friends with several girls who were interested in the radical movement. She left home at the age of sixteen over her father's objections to her new friends.[1] In 1871–1872, together with these friends, she joined the Circle of Tchaikovsky. In 1872–1873 and 1874–1877, she worked in the provinces of Samara, Tver, and Simbirsk. During this period, she received diplomas as a teacher and a medical assistant.

A prominent fellow member of the Circle of Tchaikovsky, Peter Kropotkin, said the following of Perovskaya:

In her moral conceptions she was a "rigorist", but not in the least of the sermon-preaching type. Perovskaya was a "populist" to the very bottom of her heart and at the same time a revolutionist, a fighter of the truest steel. She said to me once: "We have begun a great thing. Two generations perhaps will succumb in the task, and yet it must be done."[1]

In 1873, Perovskaya maintained several conspiracy apartments in Saint Petersburg for secret anti-tsarist propaganda meetings that had not been sanctioned by the authorities. In January 1874, she was arrested and placed in the Peter and Paul fortress in connection with the Trial of the 193. She was acquitted in 1877–1878. Perovskaya also took part in an unsuccessful attempt to free Ippolit Myshkin, a revolutionary and a member of Narodnaya Volya. In the summer of 1878, Perovskaya became a member of Zemlya i Volya, was soon arrested again, and banished to the Olonets Governorate. She managed to escape on her way to exile and went underground.

As a member of Zemlya I Volya, Perovskaya went to Kharkov in order to organize the liberation of political prisoners from the central prison. In the fall of 1879, she became a member of the Executive Committee and later a member of the administrative committee of Zemlya i Volya. Perovskaya propagandized among students, soldiers, and workers, took part in organizing the Worker's Gazette, and maintained ties with political prisoners in Saint Petersburg. In November, 1879 she took part in an attempt to blow up the imperial train on its way from Saint Petersburg to Moscow. The attempt failed. On her return to Saint Petersburg she joined Narodnaya Volya.[1]

Assassination of Alexander II

Perovskaya participated in preparing assassination attempts on Alexander II of Russia near Moscow (November, 1879), in Odessa (spring of 1880), and Saint Petersburg (the attempt that eventually killed him, 1 March 1881). She was the closest friend and later the wife of Andrei Zhelyabov, a member of the executive committee of Narodnaya Volya. Zhelyabov was to have directed the bombing attack, with the group of four bomb-throwers - Ignacy Hryniewiecki, Nikolai Kibalchich, Timofey Mikhailov, and Nikolai Rysakov. However, when Zhelyabov was arrested two days prior to the attack, Perovskaya took the role.[3]

The night before the attack, Perovskaya helped assemble the bombs.[4][5]

On Sunday morning, 13 March [1 March, Old Style], the bomb-throwers gathered at the group's flat on Telezhnaya Street. At 9–10 AM, Perovskaya and Kibalchich each brought two missiles.[6][3] Perovskaya would later relate that, before heading to the Catherine Canal, she, Rysakov and Hryniewiecki sat in a confectionery store located opposite of the Gostiny Dvor, impatiently waiting for the right time to intercept Alexander II's cavalcade. From there they parted ways and converged on the canal.[6]

In the afternoon, the Tsar was returning by Catherine Canal in his carriage after watching the weekly military roll call. Perovskaya, by taking out a handkerchief and blowing her nose as a predetermined signal, dispatched the assassins to the canal.[7] When the carriage was close enough for an attack, Perovskaya gave a signal, and Rysakov threw the bomb under the Tsar's carriage.[8] The autocrat survived this first action because his carriage was bulletproof but the second bomb, thrown by Ignacy Hryniewiecki, dispatched him.

Hanging

Rysakov was captured, and while in custody, in an attempt to save his life, cooperated with the investigators. His testimony implicated the other participants, and the tsarist police apprehended Sophia Perovskaya, along with others, on March 22. Rysakov established the identity of all prisoners. Although he knew many of them only by their party pseudonyms, he was able to describe the role they each had played.[9]

Just before her trial, she wrote in a letter to her mother:

My darling, I implore you to be calm, and not to grieve for me; for my fate does not afflict me in the least, and I shall meet it with complete tranquility, for I have long expected it, and known that sooner or later it must come. [...] I have lived as my convictions dictated, and it would have been impossible for me to have acted otherwise.[11]

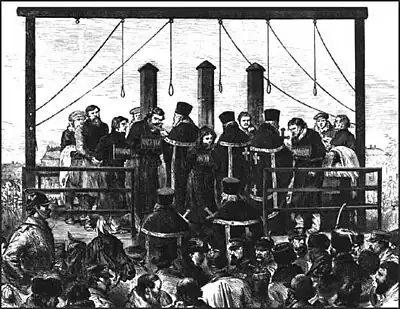

Perovskaya, along with the other conspirators were tried by the Special Tribunal of the Ruling Senate on March 26–29 and sentenced to death by hanging.[12] She was the first woman in Russia sentenced to death for terrorism.

On the morning of 15 April [3 April, Old Style], the prisoners were transported to the parade grounds of the Semenovsky Regiment, where the execution was set to take place. They were all dressed in black prison uniforms, and on their chests hung a placard with the inscription: "Regicide". Perovskaya, along with Mikhailov and Kibalchich, was placed on a cart that was drawn through the city by a pair of horses.[13] The correspondent of the London Times estimated that the execution was attended by a hundred thousand spectators. When priests ascended the gallows to give the last rites, the convicts almost simultaneously approached them and kissed the crucifix. Once the priests withdrew, Zhelyabov and Mikhailov approached Perovskaya and they kissed each other good-bye. Perovskaya had turned away from Rysakov.[14][15] Four other Pervomartovtsy, including Zhelyabov, were hanged with her.[1]

Legacy

Three decades after her death, Perovskaya would become the inspiration for the Japanese feminist Kanno Sugako, who was involved in a 1910 plan to assassinate the Emperor Meiji.[16] Kanno was also executed by hanging.

In 2018 the New York Times published a belated obituary for Perovskaya.[17]

In literature

- Henry Parkes was inspired by her to write the poem, The Beauteous Terrorist. Reproduced in full in The Beauteous Terrorist and Other Poems by Sydney Electronic Text and Image Service.

- Moss, Walter G., Alexander II and His Times: A Narrative History of Russia in the Age of Alexander II, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky. London: Anthem Press, 2002. Several chapters on Perovskaya. (available online)

- Croft, Lee B. Nikolai Ivanovich Kibalchich: Terrorist Rocket Pioneer. IIHS. 2006. ISBN 978-1-4116-2381-1. Content on Perovskaya, including her father, mother, and her unmarked burial.

- Jan Guillou uses Perovskaya in his book ”Men inte om det gälle din dotter” (”But not if it concerns your daughter”) as an example of how changes in political situation can alter the perception of a person between being a terrorist and a freedom fighter.

References

- Sack, Arkady Joseph (1918). The Birth of the Russian Democracy. Russian Information Bureau. pp. 58–60. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- Broido, Vera (1977). Apostles into Terrorists: Women and the Revolutionary Movement in the Russia of Alexander II. Viking Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-670-12961-4.

At fifteen, she entered the Alarchinsky Courses, designed to prepare girls for university studies.

- Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 276.

- Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 273.

- Kirschenbaum 2014, p. 12.

- Kel'ner 2015.

- Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 278.

- Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 280.

- Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 283.

- Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 307.

- Soviet Russia, Volume 7. Russian Soviet Government Bureau. 1922-01-01. p. 86.

- Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 287.

- Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 288.

- Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 289.

- EXECUTION OF THE CZAR'S ASSASSINS.

- Hane, Mikiso (1993). Reflections on the Way to the Gallows: Rebel Women in Prewar Japan. University of California Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-520-08421-6.

Kanno was enthusiastic about carrying out the plan, hoping to emulate Sophia Perovskaya

- "Overlooked No More: The Soviet Icon Who Was Hanged for Killing a Czar". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-05-31.

The first woman to be executed for a political crime in Russia, Perovskaya is credited with pushing the empire down the road to revolution and was later given the mantle of martyrdom.

Bibliography

- "Execution of the Czar's assassins". Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870 - 1907). 4 June 1881. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- Kel'ner, Viktor Efimovich (2015). 1 marta 1881 goda: Kazn imperatora Aleksandra II (1 марта 1881 года: Казнь императора Александра II). Lenizdat. ISBN 978-5-289-01024-7.

- Kirschenbaum, Lisa A. (2014). "The Noble Terrorist". The Women's Review of Books. 31 (5): 12–13. JSTOR 24430570.

- Yarmolinsky, Avrahm (2016). Road to Revolution: A Century of Russian Radicalism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691638546.

External links

- Recording of the 1967 Soviet film "Sophia Perovskaya" (Софья Перовская) on YouTube - removed due to copyright dispute

Media related to Sophia Lvovna Perovskaya at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sophia Lvovna Perovskaya at Wikimedia Commons