Ming (typefaces)

Ming or Song is a category of typefaces used to display Chinese characters, which are used in the Chinese, Japanese and Korean languages. They are currently the most common style of type in print for Chinese and Japanese.

| Ming | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 明體 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 明体 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Ming typeface | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Song | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 宋體 | ||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 宋体 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Song typeface | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 명조체 | ||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 明朝體 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 明朝体 | ||||||||||||||

| Kana | みんちょうたい | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Name

The names Song (or Sung) and Ming correspond to the Song dynasty when a distinctive printed style of regular script was developed, and the Ming dynasty during which that style developed into the Ming typeface style.[1] In Mainland China, the most common name is Song (the Mainland Chinese standardized Ming typeface in Microsoft Windows being named SimSun). In Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan and Korea, Ming is prevalent. In Hong Kong and Taiwan, "Song typeface" (宋体) has been traditionally used, but "Ming typeface" (明體) has gained popularity since the advent of desktop publishing. Some type foundries[2] use "Song" to refer to this style of typeface that follows a standard such as the Standard Form of National Characters, and "Ming" to refer to typefaces that resemble forms found in the Kangxi dictionary.

- Chinese: simplified Chinese: 宋体/明体; traditional Chinese: 宋體/明體; pinyin: Sòngtǐ/Míngtǐ; Jyutping: Sung3tai2/Ming4tai2

- Japanese: 明朝体; rōmaji: Minchōtai

- Korean:

- Hangul: 명조체; Hanja: 明朝體; Revised Romanization: Myeongjoche

- Hangul: 바탕체; Hanja: 바탕體; Revised Romanization: Batangche

Characteristics

Characteristics of Ming typefaces include the following:

- The basic structure of regular script

- Thick vertical strokes contrasted with thin horizontal strokes

- Triangles at the end of single horizontal strokes, called uroko (鱗, literally "fish scales") in Japanese, comparable to serifs. These are a print analog of the slight dot caused by pausing one's brush (dùn 頓), the "pause technique", used to reinforce the beginning or ending of a stroke, which is characteristic of regular script.

- Overall geometrical regularity

Possessing variable line weight and characteristic decorations at the end of lines similar to serifs, this type style is comparable to Western serif typefaces, as opposed to East Asian gothic typefaces which are comparable to Western sans-serif.

Variations

Often there are different ways to write the same Chinese character; these are collectively referred to as variant Chinese characters. Some of the differences are caused by character simplification, while others are purely orthographic differences such as stroke styling. The styling of the strokes used in old Ming typefaces came from the style used in the Kangxi Dictionary.

In mainland China, the modern standardized character forms are specified in the List of Commonly Used Characters in Modern Chinese. Some characters in the list differ from the Kangxi forms solely because they are Simplified while others differ because they use a different variant or orthography.

In Taiwan, the Standard Form of National Characters specifies the modern standardized forms. Unlike the mainland standard, the Taiwan standard uses mostly preexisting character forms but reference back to the style of regular script and reform Ming typefaces based on regular script style extensively, which had attracted criticism from many peoples.[3][4]

After the postwar kanji reforms in Japan, most of the Kangxi style characters were called kyūjitai (old style), while the reformed characters were called shinjitai, causing newer dictionaries to either incorporate both styles or omit the Kangxi styles. In Korea, most typefaces use the Kangxi forms.

There are differences between print and script forms of many Chinese characters, just as there are differences between copperplate and most people's handwriting. Some of these differences are persistent and specific to a style, but others may be no more significant than variations between individual typefaces. None of these variations usually hinder reading.

History

China

The printing industry from the Tang dynasty reached an apex in the Song dynasty,[1] during which there were three major areas of production:

- Zhejiang, where publications imitated the regular script of Ouyang Xun[1]

- Sichuan, where publications imitated the regular script of Yan Zhenqing[1]

- Fujian, where publications imitated the regular script of Liu Gongquan[1]

When Song lost control of northern China to the Jin (金) dynasty, its capital was moved to Lin'an (modern Hangzhou), where there was a revival of printing, especially literature from Tang left in what was conquered by the Jin dynasty. Many publishers were established in Lin'an, including Chén zhái shūjí pù (陳宅書籍鋪) established by Chen Qi (Chinese: 陳起),[1] from which publications used a distinct style of regular script with orderly, straight strokes. Modern typefaces of this style are classified as imitation Song typefaces (simplified Chinese: 仿宋体; traditional Chinese: 仿宋體). In the Ming dynasty, the straightening of strokes in a reprint of a publication from Lin'an started a shift to what became the basis of the Ming style.[1]

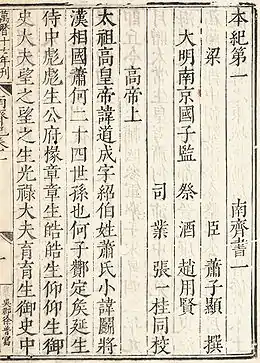

A page of a publication from Zhejiang in a regular script typeface which resembles the handwriting of Ouyang Xun.

A page of a publication from Zhejiang in a regular script typeface which resembles the handwriting of Ouyang Xun. A page of a publication from Chén zhái shūjí pù.

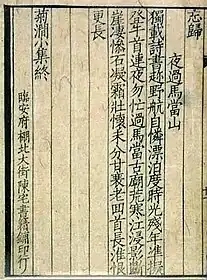

A page of a publication from Chén zhái shūjí pù.

Japan

Ming typefaces (明朝, Minchō, lit. "Ming Dynasty") are the most commonly used style in print in Japan. There are several variations in use, such as the textbook style and the newspaper style.

The creator of modern Japanese movable-type printing, Motoki Shōzō (or Motogi), modeled his sets of type after those prevailing in China, having learned an electrolytic method of type manufacturing from the American William Gamble in 1869. Motoki then created, based on Gamble's frequency studies of characters in the Chinese Bible, a full set of type with added Japanese characters; in addition to Chinese and Latin characters, Japanese text uses the syllabaries hiragana and katakana.

Korea

In Korean, a similar category of typefaces for the Korean alphabet hangul was called myeongjo (the Korean reading for the same Chinese characters "明朝") until recently, influenced by the Japanese term. A Ministry of Culture-sponsored standardization of typography terms in 1993 replaced myeongjo with batang ("바탕"), the Korean word for "foundation" or "ground" (as opposed to "figure"), and is the current term for the typeface.

Ming typefaces in computing

Technically, only Chinese characters can be printed in a Ming typeface. However, most modern typefaces (that is, digital typefaces) often also include kana glyphs in a matching style, usually in a precise style resembling handwriting with a brush. Modern Ming typefaces also incorporate Roman type glyphs for Latin characters, letterlike symbols, and numbers. In its modern role comparable to that of western serif typefaces, both kana and Latin characters are usually part of a complete typeface.

Ming typefaces are used officially by the government of China, Japan and Korea.

References

- Kinkido Type Laboratory - Home Archived 2012-05-21 at the Wayback Machine → ●知る: 漢字書体

- DynaComware typeface list which calls standardized Ming typefaces "Song" and other Ming typefaces "Ming"

- "說文:臺標之害 [刻石錄]". founder.acgvlyric.org. Retrieved 2020-06-20.

- "為甚麼不推薦新細明體 | 許瀚文 | 立場新聞". 立場新聞 Stand News. Retrieved 2020-06-20.

External links

- Nihongo resources: Japanese typefaces

- sci.lang.japan FAQ list of Japanese writing styles

- [chinese mac] Fontstypefaces included with Mac OS and Windows Archived 2007-02-05 at the Wayback Machine

- differences between some Ming typefaces

- www.kinkido.net Information on Chinese typefaces, including Ming typefaces. (in Japanese)