Sonoma, California

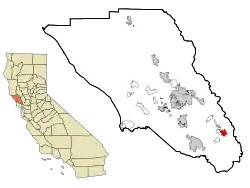

Sonoma (/səˈnoʊmə/) is a city in Sonoma County, California, United States, located in the North Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area. Sonoma is one of the principal cities of California's Wine Country and the center of the Sonoma Valley AVA. Sonoma's population was 10,739 as of the 2020 census,[9] while the Sonoma urban area had a population of 32,679.[12] Sonoma is a popular tourist destination, owing to its Californian wineries, noted events like the Sonoma International Film Festival, and its historic center.

Sonoma, California | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) .jpg.webp) _(cropped).jpg.webp)  Top: Sonoma City Hall (left) and shops around Sonoma Plaza (right); middle: shops on Spain St.; bottom: Mission San Francisco Solano | |

| |

Sonoma, California Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 38°17′20″N 122°27′32″W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Sonoma |

| laid out | 1835 |

| Incorporated | September 3, 1883[2] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager[3] |

| • Mayor | Sandra Lowe[4] |

| • City Manager | David Guhin[5] |

| Area | |

| • City | 2.74 sq mi (7.11 km2) |

| • Land | 2.74 sq mi (7.11 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) 0% |

| Elevation | 85 ft (26 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 10,739[9] |

| • Estimate (2020-04)[10] | 11,024 |

| • Density | 4,017.49/sq mi (1,551.39/km2) |

| • Metro | 483,878 |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 95476 |

| Area code | 707 |

| FIPS code | 06-72646 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 277617, 2411929 |

| Website | www |

Sonoma's origins date to 1823, when José Altimira established Mission San Francisco Solano, under the direction of Governor Luis Antonio Argüello. Following the Mexican secularization of the missions, famed Californio statesman Mariano G. Vallejo founded Sonoma on the former mission's lands in 1835. Sonoma served as the base of General Vallejo's operations until the Bear Flag Revolt in 1846, when American filibusters overthrew the local Mexican government and declared the California Republic, ushering in the American Conquest of California.

History

When the first Europeans arrived, the area was near the northeast corner of the Coast Miwok territory,[13] with Southern Pomo to the northwest, Wappo to the northeast, Suisunes and Patwin peoples to the east.[14][15]

Mission era

.png.webp)

Mission San Francisco Solano is the direct predecessor to the founding of Sonoma. The mission, the only to be constructed not by the Spanish but by the Mexican authorities, was built as part of a larger plan Governor Luis Antonio Argüello had devised to fortify Mexican presence north of San Francisco Bay and thus deter Russian encroachment into the region.[16] Franciscan padre José Altimira worked with Governor Argüello to plan the mission, against the desires of José Francisco de Paula Señan, then the President-General of the Californian missions, who disapproved of government intervention into religious matters.

In 1833 the Mexican Congress passed the Mexican secularization act of 1833, effectively nationalizing all the missions and associated lands of the Catholic church in California, which the goal of diminishing the church's highly influential standing in California's economy and political system.[17] Governor José Figueroa appointed Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, then the Commandant of the Presidio of San Francisco, as administrator (comisionado) to oversee the closing of Mission San Francisco Solano and its conversion into a civilian town.[18]

General Vallejo era

Governor Figueroa had received instructions from the Mexican Congress to establish a strong presence in the region north of the San Francisco Bay to protect the area from encroachments of foreigners.[19] An immediate concern was the further eastward movement of the Russian America Company from their settlements at Fort Ross and Bodega Bay on the California coast.[20]

Figueroa's next step in implementing his instructions was to name Lieutenant Vallejo as Military Commander of the Northern Frontier and to order the soldiers, arms and materiel at the Presidio of San Francisco moved to the site of the recently secularized Mission San Francisco Solano. The Sonoma Barracks were built to house the soldiers. Until the building was habitable, the troops were housed in the buildings of the old Mission.[21] In 1834, George C. Yount, the first Euro-American permanent settler in the Napa Valley, was employed as a carpenter by General Vallejo.

The Governor granted Lieutenant Vallejo the initial lands (approximately 44,000 acres (178 km2)) of Rancho Petaluma immediately west of Sonoma. Vallejo was also named Director of Colonization which meant that he could initiate land grants for other colonists (subject to the approval of the governor) and the diputación (Alta California's legislature).[22]

Vallejo had also been instructed by Governor Figueroa to establish a pueblo at the site of the old Mission. In 1835, with the assistance of William A. Richardson, he laid out, in accordance with the Spanish Laws of the Indies, the streets, lots, central plaza and broad main avenue of the new Pueblo de Sonoma.[23]

Although Sonoma had been founded as a pueblo in 1835, it remained under military control, lacking the political structures of municipal self-government of other Alta California pueblos. In 1843, Lieutenant Colonel Vallejo wrote to the Governor recommending that a civil government be organized for Sonoma. A town council (ayuntamiento) was established in 1844 and Jacobo Leese was named first alcalde, and Cayetano Juárez second alcalde.[24]

Bear Flag Revolt

.png.webp)

Before dawn on Sunday, June 14, 1846, thirty-three Americans, already in rebellion against the Alta California government, arrived in Sonoma. Some of the group had traveled from the camp of U.S. Army Brevet Captain John C. Frémont who had entered California illegally in late 1845 with his exploration and mapping expedition. Others had joined along the way. As the number of immigrants arriving in California had swelled, the Mexican government barred them from buying or renting land and threatened them with expulsion because they had entered without official permission.[25][26] Mexican officials were concerned about the coming war with the United States coupled with the growing influx of American immigrants into California.[27]

A group of rebellious Americans had departed from Frémont's camp on June 10 and captured a herd of 170 Mexican government-owned horses being moved by Californio soldiers from San Rafael and Sonoma to Alta California's Commandante General José Castro in Santa Clara.[28] The insurgents next determined to seize the weapons and materiel stored in the Sonoma Barracks and to deny Sonoma to the Californios as a rallying point north of San Francisco Bay.[29]

Meeting no resistance, they approached the home of General Vallejo, who invited the filibusters' leaders into his home to negotiate terms. However, when the agreement was presented to those outside they refused to endorse it. Rather than releasing the Mexican officers under parole, they insisted they be held as hostages. William Ide gave an impassioned speech urging the rebels to stay in Sonoma and start a new republic.[30] Afterwards, Vallejo and his three associates were taken as prisoners and placed on horseback and taken to Frémont.[31]

The Sonoma Barracks became the headquarters for the remaining twenty-four rebels, who within a few days created their Bear Flag. After the flag was raised Californios called the insurgents Los Osos (The Bears) because of their flag and in derision of their often scruffy appearance. The rebels embraced the expression, and their uprising became known as the Bear Flag Revolt.[32] There were some small unit skirmishes between the Bears and the Californios but no major confrontations.

After hearing reports that General José Castro was preparing to attack Sonoma, Frémont left Sutter's Fort with his forces for Sonoma. There he called a meeting with "the Bears" and united his forces with the revolters to form a single military unit. Frémont then took the majority of the men back to Sutter's Fort and left fifty men to defend Sonoma. The Bear Flag Revolt ended and the California Republic ceased to exist on July 9 when Lieutenant Joseph Warren Revere of the U.S. Navy raised the United States flag in front of the Sonoma Barracks.[33]

Post-Conquest era

Following the American Conquest of California and the advent of the California Gold Rush, local businesses prospered with the business brought by the soldiers as well as miners traveling to and from the gold fields. The prosperity and optimism about Sonoma's future promoted land speculation which was particularly problematic because of the cloudy records regarding land ownership.

Vallejo had granted land by virtue of his office as Director of Colonization before the pueblo was organized. Among the traditional duties of Alta California's alcaldes was the selling of town lots. Political factions backed different Sonoma alcaldes (John H. Nash, supported by American immigrants, and Lilburn Boggs supported by Vallejo and the Californios) made the situation more complex.[34] Some property was sold more than once.[35] A valid land sale depended on proof of the seller's chain of title. Over thirty years of lawsuits were required before land owners in Sonoma were able to obtain clear titles.[36]

When the U.S. military occupation of California ended in 1850, when California was admitted as a state, Sonoma was named the county seat for Sonoma County. About that time the flow of miners had slowed and the U.S. Army was leaving Sonoma. Business in Sonoma moved into a recession in 1851.[37] Surrounding towns such as Petaluma and Santa Rosa were developing and gaining population faster than Sonoma. An 1854 special election moved the county seat and its entailed economic activity to Santa Rosa.

Contemporary era

The United States Navy operated a rest center at the Mission Inn through World War II.[38]

Parts of Wes Craven's Scream (1996) were filmed in the city, with shots of the Sonoma Community Center masked as Westboro High School.[39]

Geography

The city is situated in the Sonoma Valley, with the Mayacamas Mountains to the east and the Sonoma Mountains to the west, with the prominent landform Sears Point to the southwest. Sonoma has an area of 2.7 sq mi (7.0 km2).

The principal watercourse in the town is Sonoma Creek, which flows in a southerly direction to discharge ultimately to the Napa Sonoma Marsh; Arroyo Seco Creek is a tributary to Schell Creek with a confluence in the eastern portion of the town. The active Rodgers Fault lies to the west of Sonoma Creek; however, the risk of major damage is mitigated by the fact that most of the soils beneath the city consist of a slight alluvial terrace underlain by strongly cemented sedimentary and volcanic rock.[40] To the immediate south, west and east are deeper rich, alluvial soils that support valuable agricultural cultivation. The mountain block to the north rises to 1,200 feet (366 m) and provides an important scenic backdrop.

Climate

Sonoma has a typical lowland near-coastal Californian warm-summer mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csb) with hot, dry summers (although nights are comfortably cool) and cool, wet winters. In January, the normal high is 57.2 °F (14.0 °C) and the typical low is 37.2 °F (2.9 °C). In July, the normal high is 88.6 °F (31.4 °C) and the normal low is 51.2 °F (10.7 °C). There are an average of 58.1 days with highs of 90 °F (32 °C) or higher and 12.1 days with highs of 100 °F (38 °C). The highest temperature on record was 116 °F (47 °C) on July 13, 1972, and the lowest temperature was 13 °F (−11 °C) on December 22, 1990. Normal annual precipitation is 29.43 inches (748 mm). The wettest month on record was 20.29 inches (515 mm) in January 1995. The greatest 24-hour rainfall was 6.75 inches (171 mm) on January 4, 1982. There are an average of 68.6 days with measurable precipitation. Snow has rarely fallen, but 1 inch (2.5 cm) fell in January 1907; more recently, snow flurries were observed on February 5, 1976, and in the winter of 2001.[41]

| Climate data for Sonoma, California, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 84 (29) |

98 (37) |

90 (32) |

100 (38) |

105 (41) |

112 (44) |

116 (47) |

108 (42) |

110 (43) |

107 (42) |

91 (33) |

80 (27) |

116 (47) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 67.2 (19.6) |

73.0 (22.8) |

78.3 (25.7) |

85.2 (29.6) |

91.1 (32.8) |

100.3 (37.9) |

101.1 (38.4) |

100.4 (38.0) |

99.1 (37.3) |

91.3 (32.9) |

78.6 (25.9) |

67.2 (19.6) |

104.0 (40.0) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 57.0 (13.9) |

61.6 (16.4) |

65.4 (18.6) |

69.2 (20.7) |

75.3 (24.1) |

82.8 (28.2) |

86.0 (30.0) |

86.1 (30.1) |

84.8 (29.3) |

77.5 (25.3) |

65.2 (18.4) |

56.7 (13.7) |

72.3 (22.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 47.7 (8.7) |

50.8 (10.4) |

53.7 (12.1) |

56.7 (13.7) |

61.6 (16.4) |

67.1 (19.5) |

69.7 (20.9) |

69.6 (20.9) |

68.0 (20.0) |

62.5 (16.9) |

53.5 (11.9) |

47.4 (8.6) |

59.0 (15.0) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 38.4 (3.6) |

40.1 (4.5) |

41.9 (5.5) |

44.1 (6.7) |

47.8 (8.8) |

51.3 (10.7) |

53.5 (11.9) |

53.2 (11.8) |

51.2 (10.7) |

47.4 (8.6) |

41.8 (5.4) |

38.2 (3.4) |

45.7 (7.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 27.8 (−2.3) |

30.0 (−1.1) |

32.6 (0.3) |

35.1 (1.7) |

40.0 (4.4) |

44.0 (6.7) |

47.3 (8.5) |

47.0 (8.3) |

44.1 (6.7) |

38.0 (3.3) |

31.4 (−0.3) |

27.7 (−2.4) |

25.6 (−3.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 20 (−7) |

20 (−7) |

24 (−4) |

20 (−7) |

27 (−3) |

31 (−1) |

35 (2) |

36 (2) |

34 (1) |

30 (−1) |

22 (−6) |

13 (−11) |

13 (−11) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.47 (139) |

5.42 (138) |

3.84 (98) |

1.78 (45) |

1.03 (26) |

0.32 (8.1) |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.06 (1.5) |

0.07 (1.8) |

1.52 (39) |

3.01 (76) |

5.83 (148) |

28.35 (720.4) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.4 | 10.9 | 9.8 | 6.5 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 3.6 | 7.5 | 11.8 | 67.6 |

| Source 1: NOAA[42] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: XMACIS2[43] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 757 | — | |

| 1900 | 652 | −13.9% | |

| 1910 | 957 | 46.8% | |

| 1920 | 801 | −16.3% | |

| 1930 | 980 | 22.3% | |

| 1940 | 1,158 | 18.2% | |

| 1950 | 2,015 | 74.0% | |

| 1960 | 3,023 | 50.0% | |

| 1970 | 4,259 | 40.9% | |

| 1980 | 6,054 | 42.1% | |

| 1990 | 8,121 | 34.1% | |

| 2000 | 9,128 | 12.4% | |

| 2010 | 10,648 | 16.7% | |

| 2020 | 10,739 | 0.9% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 11,024 | [10] | 3.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[44] | |||

2010

The 2010 United States Census[45] reported that Sonoma had a population of 10,648. The population density was 3,883.3 inhabitants per square mile (1,499.4/km2). The racial makeup of Sonoma was 9,242 (86.8%) White, 52 (0.5%) African American, 56 (0.5%) Native American, 300 (2.8%) Asian, 23 (0.2%) Pacific Islander, 711 (6.7%) from other races, and 264 (2.5%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1,634 persons (15.3%).

Within the Sonoma Valley, the racial makeup was 46.3% White, 49.1% Hispanic, and 2.7% Native American. The average household income was $96,722. The Census reported that 10,411 people (97.8% of the population) lived in households, 11 (0.1%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 226 (2.1%) were institutionalized.

There were 4,955 households, out of which 1,135 (22.9%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 2,094 (42.3%) were married couples living together, 425 (8.6%) had a female householder with no husband present, 174 (3.5%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 230 (4.6%) unmarried partnerships, and 48 (1.0%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 1,920 households (38.7%) were made up of individuals, and 1,054 (21.3%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.10. There were 2,693 families (54.3% of all households); the average family size was 2.82.

The population was spread out, with 1,920 people (18.0%) under the age of 18, 559 people (5.2%) aged 18 to 24, 2,252 people (21.1%) aged 25 to 44, 3,250 people (30.5%) aged 45 to 64, and 2,667 people (25.0%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 49.2 years. For every 100 females, there were 83.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 78.8 males.

There were 5,544 housing units at an average density of 2,021.9 per square mile (780.7/km2), of which 2,928 (59.1%) were owner-occupied, and 2,027 (40.9%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.6%; the rental vacancy rate was 7.0%. 6,294 people (59.1% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 4,117 people (38.7%) lived in rental housing units.

2000

At the previous census[12] of 2000, there were 9,128 people, 4,373 households, and 2,361 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,442/sq mi (1,330/km2). There were 4,671 housing units at an average density of 1,762 per square mile (680/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 93.80% White, 0.36% African American, 0.34% Native American, 1.70% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 1.61% from other races, and 2.14% from two or more races. 6.85% of the population were Hispanics (of any race).

There were 4,373 households, of which 21.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 42.5% were married couples living together, 8.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 46.0% were non-families. 39.2% of households consisted of individuals, and 21.5% had someone living alone who was 65 or older. The average household size was 2.07 and the average family size was 2.77. The age distribution was as follows: 18.6% under the age of 18, 4.8% from 18 to 24, 23.5% from 25 to 44, 28.9% from 45 to 64, and 24.2% who had achieved age 65. The median age was 47 years. For every 100 females, there were 81.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 77.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $50,505, and the median income for a family was $65,600. Males had a median income of $51,831 versus $40,276 for females. The per capita income for the city was $32,387. 3.7% of the population and 2.0% of families were below the poverty line. 3.3% of those under 18 and 4.7% of those were 65 and older.

Government

.jpg.webp)

The City of Sonoma was incorporated on September 3, 1883.[2] It uses a council–manager form of government, wherein a council sets policy and hires staff to implement it. The city council has five members, elected to four-year terms.[3] The city council selects one of its members to serve as mayor.

In addition to the official mayor, Sonoma has a tradition of naming an honorary mayor each year, titled "Alcalde/Alcaldesa".[46] The Alcalde or Alcaldesa presides over ceremonial events for the city.

State and federal representation

In the California State Legislature, Sonoma is in the 3rd Senate District, represented by Democrat Bill Dodd, and in the 10th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Stephanie Nguyen.[47]

In the United States House of Representatives, Sonoma is in California's 4th congressional district, represented by Democrat Mike Thompson.[48]

According to the California Secretary of State, as of February 10, 2019, Sonoma has 7,162 registered voters. Of those, 3,694 (51.6%) are registered Democrats, 1,309 (18.3%) are registered Republicans, and 1,783 (24.9%) have declined to state a political party.[49]

Media

The two primary news sources for Sonoma are the Sonoma Index-Tribune and the Sonoma Valley Sun. The Sonoma Index-Tribune publishes twice weekly on Tuesdays and Fridays and has a circulation of 9,000. The Sonoma Valley Sun publishes every other Thursday and is free. The Sun is recognized as the alternative weekly for the Sonoma Valley. It has a circulation of 5,000. Sonoma has a local radio station, KSVY, and a public-access television station, SVTV 27.

Infrastructure

Transportation

California State Route 12 is the main route in Sonoma, passing through the populated areas of the Sonoma Valley and connecting it to Santa Rosa to the north and Napa to the east. State routes 121 and 116 run to the south of town, passing through the unincorporated area of Schellville and connecting Sonoma Valley to Napa, Petaluma to the west, and Marin County to the south. Sonoma County Transit provides bus service from Sonoma to other points in the county. VINE Transit also operates a route between Napa and Sonoma.

The nearest airport with regularly scheduled commercial passenger service is Charles M. Schulz–Sonoma County Airport, about 30 miles (50 km) northwest of Sonoma. San Francisco International Airport and Oakland International Airport are both about 60 miles (100 km) south of Sonoma.

Notable people

- Hap Arnold, first General of the United States Air Force

- Rod Beaton, American journalist and media executive with United Press International[50][51]

- Phil Coturri, viticulturalist who is recognized as pioneering organic and biodynamic farming

- Tommy Everidge, professional Major League Baseball player

- Kirk Hammett, lead guitarist of Metallica and songwriter

- Agoston Haraszthy, the "father of Californian wine"

- Joseph Hooker, politician and Civil War general[52]

- John Lasseter, animator and former chief creative executive of Pixar

- Tony Moll, former NFL player

- Brian Posehn, comedian and actor

- Don Sebastiani, vintner and politician - Sebastiani Vineyards and Winery

- Tim Schafer, American computer game designer and founder of Double Fine Productions

- William Smith, American Revolutionary War veteran believed to be buried in California[53]

- Tom Smothers, comedian and musician

- Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, the last Mexican military commander of northern California

- Ignazio Vella, American businessman who served on the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors

- Sanford Weill, former chairman of Citicorp during 2007–2008 financial crisis

- Chuck Williams, founder of Williams Sonoma

- Paula Wolfert and husband William Bayer, both authors, have been resident in Sonoma since 1998

In popular culture

Apple's desktop operating system, macOS Sonoma, announced on June 5, 2023, during WWDC, is named after the city.[54]

Sister cities

- Aswan, Egypt

- Chambolle-Musigny, France

- Greve in Chianti, Italy

- Kaniv, Ukraine

- Pátzcuaro, Mexico

- Penglai (Yantai), China

- Tokaj, Hungary

See also

- Enos v. Snyder (1900)

- Swiss Hotel

References

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- "City Council Overview". City of Sonoma. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- Charrier, Emily (May 24, 2023). "Gubernatorial candidate Betty Yee swings by Sonoma". The Sonoma Index-Tribune. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- Hunter, Chase (April 13, 2023). "Sonoma City Council selects new city manager". The Sonoma Index-Tribune. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- "Sonoma". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- "Sonoma (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- Population. In: QuickFacts: Sonoma city, California. Census, April 1, 2020. Census.gov. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "American FactFinder - Results". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- SSHP-GP p.11

- S/PSHPA

- CIMCC

- Bancroft p. 496

- Smilie p. 34

- Bancroft III:720

- Bancroft 3:246

- Smilie p.54

- Stammerjohan p.25

- Smilie p. 50

- Bancroft III:721

- Bancroft IV: 678 note 16

- Bancroft; IV: 598-608

- Richman p 308

- Hague p.118

- Ide p. 112-3

- Bancroft V:109

- Harlow p. 102

- Bancroft V:117

- SSHP-GP p. 82

- Bancroft V:185-86

- Parmelee p. 90-93

- Bancroft V:668-670

- Parmelee p. 94

- Parmelee p. 101

- "U.S. Naval Activities World War II by State". Patrick Clancey. Archived from the original on September 7, 2011. Retrieved March 19, 2012.

- Daniel Farrands (Director) Thommy Hutson (Writer) (April 6, 2011). Scream: The Inside Story (TV). United States: The Biography Channel Video.

- General Plan, City of Sonoma, California, prepared for the City of Sonoma by Hall and Goodhue Community Design Group, San Francisco, Ca. (1974)

- "General Climate Summary Tables - Sonoma, California". Western Regional Climate Center. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Sonoma, CA". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- "xmACIS2". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Sonoma city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 11, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- "Recognizing Alcaldessa Elizabeth Kemp Of Sonoma, California". Archived from the original on September 20, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- "California's 4th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- "CA Secretary of State – Report of Registration – February 10, 2019" (PDF). ca.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 23, 2019. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- United Press International (July 6, 2002). "Former UPI president, Rod Beaton dies". United Press International. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- "Roderick Beaton, 79, Former U.P.I. Leader". The New York Times. New York, New York. Associated Press. July 14, 2002. p. 33. Retrieved January 13, 2022.; "Rod Beaton". Asbury Park Press. Asbury Park, New Jersey. Associated Press. July 9, 2002. p. 20.

- Sheridan, Lorna (April 10, 2017). "Sonoma's historic Hooker House lures new tenant". Sonoma Index-Tribune. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- Lely, Ryan (May 22, 2008). "Sailor of the Unknown Tomb". Features. Sonoma Valley Sun. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- Heater, Brian (June 5, 2023). "Apple debuts macOS 14 Sonoma". TechCrunch. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

Bibliography

- Alexander, James B. (1986). Sonoma Valley Legacy. Sonoma, CA: Sonoma Valley Historical Society.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1886). History of California Vol. II-V. The History Company, San Francisco, CA.

- CIMCC. "San Francisco de Solano - General Information". California Indian Museum and Cultural Center. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- Court of Claims (United States). "Mariano G Vallejo vs. The United States". Case 566.

- CSMM, The California State Military Museum. "Captain John Charles Fremont and the Bear Flag Revolt". Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- Fremont, John Charles; Fremont, Jessie Benton (1887). Memoirs of My Life, Vol. 1. Belford, Clarke. ISBN 9780608422800.

- Hague, Harlan & David J. Langum Thomas O. Larkin: A Life of Patriotism and Profit in Old California, University of Oklahoma Press, (1990)

- Harlow, Neal California Conquered: The Annexation of a Mexican Province 1846–1850, ISBN 0-520-06605-7, (1982)

- Parmelee, Robert D (1972). Pioneer Sonoma. Sonoma, CA: The Sonoma Valley Historical Society.

- Richman, Irving B. (1911). California Under Spain and Mexico, 1535-1847. The Riverside Press, Cambridge. ISBN 9781404750784.

- Smilie, Robert A. (1975). The Sonoma Mission, San Francisco Solano de Sonoma: The Founding, Ruin and Restoration of California's 21st Mission. Valley Publishers, Fresno, CA. ISBN 978-0-913548-24-0.

- S/PSHPA - Sonoma/Petaluma State Historic Parks Association. "Mission San Francisco Solano". Archived from the original on August 3, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2014.

- SSHP. "Sonoma State Historic Park - A Short History of Historical Archaeology". California Department of Parks and Recreation. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- SSHP-GP. "Sonoma State Historic Park - General Plan" (PDF). California Department of Parks and Recreation. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- Stammerjohan, George. Sonoma Barracks, A Military View. Department of Parks and Recreation, State of California.

- Walker, Dale L. (1999). Bear Flag Rising: The Conquest of California, 1846. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0312866853.

.jpg.webp)