Super Nintendo Entertainment System

The Super Nintendo Entertainment System, commonly shortened to Super Nintendo,[lower-alpha 2] Super NES or SNES,[lower-alpha 3] is a 16-bit home video game console developed by Nintendo that was released in 1990 in Japan and South Korea,[16] 1991 in North America, 1992 in Europe and Oceania, and 1993 in South America. In Japan, it is called the Super Famicom (SFC).[lower-alpha 4] In South Korea, it is called the Super Comboy[lower-alpha 5] and was distributed by Hyundai Electronics.[17] The system was released in Brazil on August 30, 1993,[16][18] by Playtronic. Although each version is essentially the same, several forms of regional lockout prevent cartridges for one version from being used in other versions.

| |

| |

| Also known as | SNES Super NES Super Nintendo |

|---|---|

| Developer | Nintendo R&D2 |

| Manufacturer | Nintendo |

| Type | Home video game console |

| Generation | Fourth |

| Release date | |

| Lifespan | 1990–2005[7] |

| Introductory price | ¥25,000 US$199 |

| Discontinued | |

| Units sold |

|

| Media | ROM cartridge |

| CPU | Ricoh 5A22 @ 3.58 MHz |

| Sound | Nintendo S-SMP |

| Online services | Satellaview (Japan only) XBAND (US and Canada only) Nintendo Power (Japan only) |

| Best-selling game |

|

| Predecessor | Nintendo Entertainment System |

| Successor | Nintendo 64 |

The Super NES is Nintendo's second programmable home console, following the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). The console introduced advanced graphics and sound capabilities compared with other systems at the time. It was designed to accommodate the ongoing development of a variety of enhancement chips integrated into game cartridges to be competitive into the next generation.

The Super NES received largely positive reviews and was a global success, becoming the bestselling console of the 16-bit era after launching relatively late and facing intense competition from Sega's Genesis console in North America and Europe. Overlapping the NES's 61.9 million unit sales, the Super NES remained popular well into the 32-bit era, with 49.1 million units sold worldwide by the time it was discontinued in 2003. It continues to be popular among collectors and retro gamers, with new homebrew games and Nintendo's emulated rereleases, such as on the Virtual Console, the Super NES Classic Edition, Nintendo Switch Online; as well as several non-console emulators which operate on a desktop computer or mobile device, such as Snes9x.

History

To compete with the popular Family Computer in Japan, NEC Home Electronics launched the PC Engine in 1987, and Sega followed suit with the Mega Drive in 1988. The two platforms were later launched in North America in 1989 as the TurboGrafx-16 and the Sega Genesis respectively. Both systems were built on 16-bit architectures and offered improved graphics and sound over the 8-bit NES. It took several years for Sega's system to become successful.[19] Nintendo executives were in no rush to design a new system, but they reconsidered when they began to see their dominance in the market slipping.[20] Bill Mensch, the co-creator of the 8-bit MOS Technology 6502 microprocessor and founder of the Western Design Center (WDC), gave Ricoh the exclusive right to supply 8-bit and 16-bit WDC microprocessors for the new system.[21] Meanwhile, Sony engineer Ken Kutaragi reached an agreement with Nintendo to design the console's sound chip without notifying his supervisors, who were enraged when they discovered the project; though Kutaragi was nearly fired, then-CEO Norio Ohga intervened in support of the project and gave him permission to complete it.[22]

On September 9, 1987, then-Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi revealed the development of the Super Famicom in the newspaper Kyoto Shimbun. On August 30, 1988, in an interview with TOUCH Magazine, he announced the development of Super Mario Bros. 4, Dragon Quest V, three original games, and he projected sales of 3 million units of the upcoming console. Famicom Hissyoubon magazine speculated that Yamauchi's early announcement was probably made to forestall Christmas shopping for the PC Engine, and relayed Enix's clarification that it was waiting on sales figures to select either PC Engine or Super Famicom for its next Dragon Quest game. The magazine and Enix both expressed a strong interest in networking as a standard platform feature.[23][24] The console was demonstrated to the Japanese press on November 21, 1988, and again on July 28, 1989.[25][26]

Launch

Designed by Masayuki Uemura, the designer of the original Famicom, the Super Famicom was released in Japan on Wednesday, November 21, 1990, for ¥25,000 (equivalent to ¥27,804 in 2019). It was an instant success. Nintendo's initial shipment of 300,000 units sold out within hours, and the resulting social disturbance led the Japanese government to ask video game manufacturers to schedule future console releases on weekends.[27] This gained the attention of the Yakuza criminal organization, so the devices were shipped at night to avoid robbery.[28]

With the Super Famicom quickly outselling its rivals, Nintendo reasserted itself as the leader of the Japanese console market.[29] Nintendo's success was partially due to the retention of most of its key third-party developers, including Capcom, Konami, Tecmo, Square, Koei, and Enix.[30]

Nintendo released the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, a redesigned version of the Super Famicom, in North America for US$199 (equivalent to $430 in 2022). It began shipping in limited quantities on August 23, 1991,[lower-alpha 1][36] with an official nationwide release date of September 9, 1991.[37] The Super NES was released in the United Kingdom and Ireland in April 1992 for £150 (equivalent to £330 in 2021).[38]

Most of the PAL region versions of the console use the Japanese Super Famicom design, except for labeling and the length of the joypad leads. The Playtronic Super NES in Brazil, although PAL-M, uses the North American design.[39] Both the NES and Super NES were released in Brazil in 1993 by Playtronic, a joint venture between the toy company Estrela and consumer electronics company Gradiente.[40]

The Super NES and Super Famicom launched with few games, but these games were well received. In Japan, only two games were initially available: Super Mario World and F-Zero.[41] Bombuzal was released during the launch week.[42] In North America, Super Mario World was launched as a bundle with the console; other launch games include F-Zero, Pilotwings (both of which demonstrate the console's Mode 7 pseudo-3D rendering), SimCity, and Gradius III.[43]

Console wars

The rivalry between Nintendo and Sega was described as one of the most notable console wars in video game history,[44] in which Sega positioned the Genesis as the "cool" console, with games aimed at older audiences, and aggressive advertisements that occasionally attacked the competition.[45] Nintendo scored an early public-relations advantage by securing the first console conversion of Capcom's arcade hit Street Fighter II for Super NES, which took more than a year to make the transition to the Genesis. Though the Genesis had a two-year lead to launch time, a much larger library of games, and a lower price point,[46] it only represented an estimated 60% of the American 16-bit console market in June 1992,[47] and neither console could maintain a definitive lead for several years. Donkey Kong Country is said to have helped establish the Super NES's market prominence in the latter years of the 16-bit generation,[48][49][50][51] and for a time, maintain against the PlayStation and Saturn.[52] According to Nintendo, the company had sold more than 20 million Super NES units in the U.S.[53] According to a 2014 Wedbush Securities report based on NPD sales data, the Super NES outsold the Genesis in the U.S. market by 1.5 million units.[54]

Changes in policy

During the NES era, Nintendo maintained exclusive control over games released for the system – the company had to approve every game, each third-party developer could only release up to five games per year (but some third parties got around this by using different names, such as Konami's "Ultra Games" brand), those games could not be released on another console within two years, and Nintendo was the exclusive manufacturer and supplier of NES cartridges. Competition from Sega's console brought an end to this practice; in 1991, Acclaim Entertainment began releasing games for both platforms, with most of Nintendo's other licensees following suit over the next several years; Capcom (which licensed some games to Sega instead of producing them directly) and Square were the most notable holdouts.[55]

Nintendo continued to carefully review submitted games, scoring them on a 40-point scale and allocating marketing resources accordingly. Each region performed separate evaluations.[56] Nintendo of America also maintained a policy that, among other things, limited the amount of violence in the games on its systems. The surprise arcade hit Mortal Kombat (1992), a gory fighting game with huge splashes of blood and graphically violent fatality moves, was heavily censored by Nintendo.[lower-alpha 6] Because the Genesis version allowed for an uncensored version via cheat code,[57] it outsold the censored Super NES version by a ratio of nearly three to one.[58]

U.S. Senators Herb Kohl and Joe Lieberman convened a Congressional hearing on December 9, 1993, to investigate the marketing of violent video games to children.[lower-alpha 7] Though Nintendo took the high ground with moderate success, the hearings led to the creation of the Interactive Digital Software Association and the Entertainment Software Rating Board and the inclusion of ratings on all video games.[57][58] With these ratings in place, Nintendo decided its censorship policies were no longer needed.[58]

32-bit era and beyond

While other companies were moving on to 32-bit systems, Rare and Nintendo proved that the Super NES was still a strong contender in the market. In November 1994, Rare released Donkey Kong Country, a platform game featuring 3D models and textures pre-rendered on Silicon Graphics workstations. With its detailed graphics, fluid animation, and high-quality music, Donkey Kong Country rivals the aesthetic quality of games that were being released on newer 32-bit CD-based consoles. In the last 45 days of 1994, 6.1 million copies were sold, making it the fastest-selling video game in history to that date. This game conveyed that early 32-bit systems had little to offer over the Super NES, and proved the market for the more advanced consoles of the near future.[59][60] According to TRSTS reports, two of the top five bestselling games in the U.S. for December 1996 are Super NES games.[61]

In October 1997, Nintendo released a redesigned model of the Super NES (the SNS-101 model referred to as "New-Style Super NES") in North America for US$99 (equivalent to $200 in 2022), with some units including the pack-in game Super Mario World 2: Yoshi's Island.[62][63] Like the earlier New-Style NES (model NES-101), this is slimmer and lighter than its predecessor,[63] but it lacks S-Video and RGB output, and it is among the last major Super NES-related releases in the region. A similarly redesigned Super Famicom Jr. was released in Japan at around the same time.[64] The redesign stayed out of Europe.

Nintendo ceased production of the Super NES in North America in 1999,[8] about two years after releasing Kirby's Dream Land 3 (its final first-party game in the US) on November 27, 1997, and one year after releasing Frogger (its final third-party game in the US) in 1998. In Japan, Nintendo continued production of both the Family Computer and the Super Famicom until September 25, 2003,[10] and new games were produced until the year 2000, ending with the release of Metal Slader Glory Director's Cut on November 29, 2000.[65]

Many popular Super NES games were ported to the Game Boy Advance, which has similar video capabilities. In 2005, Nintendo announced that Super NES games would be made available for download via the Wii's Virtual Console service.[66] On October 31, 2007, Nintendo Co., Ltd. announced that it would no longer repair Family Computer or Super Famicom systems due to an increasing shortage of the necessary parts.[67] On March 3, 2016, Nintendo Co., Ltd. announced that it would bring Super NES games to the New Nintendo 3DS and New Nintendo 3DS XL (and later the New Nintendo 2DS XL) via its eShop download service.[68] At the Nintendo Direct event on September 4, 2019, Nintendo announced that it would be bringing select Super NES games to the Nintendo Switch Online platform.[69][70]

Hardware

Technical specifications

The 16-bit design of the Super NES[71] incorporates graphics and sound co-processors that perform tiling and simulated 3D effects, a palette of 32,768 colors, and 8-channel ADPCM audio. These base platform features, plus the ability to dramatically extend them all through substantial chip upgrades inside of each cartridge, represent a leap over the 8-bit NES generation and some significant advantages over 16-bit competitors such as the Genesis.[72]

CPU and RAM

The CPU is a Ricoh 5A22, which is a derivative of the 16-bit WDC 65C816 microprocessor. In NTSC regions, its nominal clock speed is 3.58 MHz but the CPU will slow down to either 2.68 MHz or 1.79 MHz when accessing some slower peripherals.[73]

This CPU has an 8-bit data bus and two address buses. The 24-bit "Bus A" is designated for general accesses, and the 8-bit "Bus B" can access support chip registers such as the video and audio co-processors.

The WDC 65C816 supports an 8-channel DMA unit, an 8-bit parallel I/O port a controller port interface circuits allowing serial and parallel access to controller data, a 16-bit multiplication and division unit, and circuitry for generating non-maskable interrupts on V-blank and IRQ interrupts on calculated screen positions.[73]

Early revisions of the 5A22 used in SHVC boards are prone to spontaneous failure which can produce a variety of symptoms including graphics glitches in Mode 7, a black screen on power-on, or improperly reading the controllers.[74] The first revision 5A22 has a fatal bug in the DMA controller that can crash games; this was corrected in subsequent revisions.[75]

The console contains 128 KB of general-purpose RAM, which is separate from the 64 KB VRAM and 64 KB ARAM dedicated to the video and audio subsystems respectively.

Video

The Picture Processing Unit (PPU) consists of two closely tied IC packages. It contains 64 KB of SRAM for video data, 544 bytes of object attribute memory (OAM) for sprite data, and 256 × 15 bits of color generator RAM (CGRAM) for palette data. This CGRAM provisions up to 256 colors, chosen from the 15-bit RGB color space, from a palette of 32,768 colors. The PPU is clocked by the same signal as the CPU and generates a pixel every two or four cycles.[71]

Audio

The S-SMP audio chip consists of an 8-bit CPU, a 16-bit DSP, and 64 KB of SRAM. It was designed by Ken Kutaragi and produced by Sony[76] and is completely independent from the rest of the system. It is clocked at a nominal 24.576 MHz in both NTSC and PAL systems. It is capable of stereo sound, composed from 8 voices generated using 8 bit audio samples and various effects such as echo.[77]

Regional lockout

Nintendo employed several types of regional lockout, including both physical and hardware incompatibilities.

Physically, the cartridges are shaped differently for different regions. North American cartridges have a rectangular bottom with inset grooves matching protruding tabs in the console, and other regions' cartridges are narrower with a smooth curve on the front and no grooves. The physical incompatibility can be overcome with the use of various adapters, or through modification of the console.[78][79]

Internally, a regional lockout chip (CIC) within the console and in each cartridge prevents the PAL region games from being played on Japanese or North American consoles and vice versa. The Japanese and North American machines have the same region chip. This can be overcome through the use of adapters, typically by inserting the imported cartridge in one slot and a cartridge with the correct region chip in a second slot. Alternatively, disconnecting one pin of the console's lockout chip will prevent it from locking the console; hardware in later games can detect this situation, so it became common to install a switch to reconnect the lockout chip as needed.[80]

PAL consoles face another incompatibility when playing out-of-region cartridges: the NTSC video standard specifies video at 60 Hz but PAL operates at 50 Hz, resulting in an approximately 16.7% slower framerate. PAL's higher resolution results in letterboxing of the output image.[78] Some commercial PAL region releases exhibit this same problem and, therefore, can be played in NTSC systems without issue, but other games will face a 20% speedup if played in an NTSC console. To mostly correct this issue, a switch can be added to place the Super NES PPU into a 60 Hz mode supported by most newer PAL televisions. Later games will detect this setting and refuse to run, requiring the switch to be thrown only after the check completes.[81]

Casing

Japanese SHVC-001 model

Japanese SHVC-001 model

(1990–1998) North American SNS-001 model

North American SNS-001 model

(1991–1997) PAL-region SNSP-001A model

PAL-region SNSP-001A model

(1992–1998) New-Style Super NES SNS-101

New-Style Super NES SNS-101

(1997–1999) Japanese SHVC-101 model

Japanese SHVC-101 model

(1998–2003) South Korean SNSN-001 model

South Korean SNSN-001 model Nintendo Super System controller

Nintendo Super System controller

All models of the Super NES control deck are predominantly gray, of slightly different shades. The original North American version, designed by Nintendo of America industrial designer Lance Barr[82] (who previously redesigned the Famicom to become the NES[83]), has a boxy design with purple sliding switches and a dark gray eject lever. The loading bay surface is curved, both to invite interaction and to prevent food or drinks from being placed on the console and spilling as with the flat-surfaced NES.[82] The Japanese and European versions are more rounded, with darker gray accents and buttons.

All versions incorporate a top-loading slot for game cartridges, although the shape of the slot differs between regions to match the different shapes of the cartridges. The MULTI OUT connector (later used on the Nintendo 64 and GameCube) can output composite video, S-Video and RGB signals, as well as RF with an external RF modulator.[84][85] Original versions additionally include a 28-pin expansion port under a small cover on the bottom of the unit and a standard RF output with channel selection switch on the back;[86] the redesigned models output composite video only, requiring an external modulator for RF.[85]

The Nintendo Super System (NSS) is an arcade system for retail preview of 11 particular Super NES games in the United States, similar to the PlayChoice-10 for NES games. It consists of slightly modified Super NES hardware with a menu interface and 25-inch monitor, that allows gameplay for a certain amount of time depending on game credits.[87][88] Manufacturing of this model was discontinued in 1992.[89][90]

Redesigned model

A cost-reduced version of the console, referred to as the New-Style Super NES[85] (model SNS-101)[91] in North America and as the Super Famicom Jr.[lower-alpha 8][92] in Japan, was released late in the platform's lifespan; designed by Barr,[91] it incorporates design elements from both the original North American and Japanese/European console models[91][93] but in a smaller form factor.[94][95] Unlike the original console models, the redesigned model is virtually identical across both regions save for the color palette.[95]

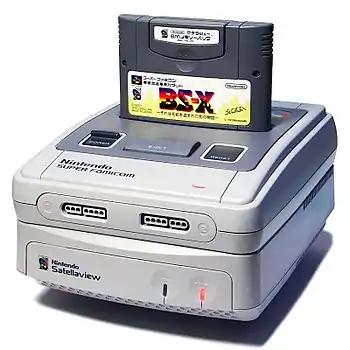

Externally, the power and reset buttons were moved to the left-hand side of the console while the cartridge eject button and power LED indicator were omitted.[94][96] Internally, the redesigned model consolidates the console's hardware into a system-on-chip (SoC) design.[97] The redesigned console lacks the bottom expansion slot, rendering it incompatible with the Japan-exclusive Satellaview add-on.[95]

For AV output, the redesigned console features the same multi-out port used on the original models.[84][98] Unlike the latter models, the former's AV port only supports composite video output natively as support for RGB video and S-Video was disabled internally; however, they can be restored via a "relatively simple" modification.[91][98] The internal RF modulator was also removed, requiring an external one for such output if needed.[85][94] Due to the SoC design, it is highly sought after by Super NES/Famicom enthusiasts since its RGB video quality (if restored) is improved over earlier internal revisions of the console.[97]

The redesigned console first released in October 1997 in North America, where it originally retailed for US$99.95 in a bundle with Super Mario World 2: Yoshi's Island;[94] it was subsequently released in Japan on March 27, 1998, where it retailed for ¥7,800.[92][99] Nintendo marketed it as an entry-level gamer's system for consumers who were apprehensive about the higher price of newer systems such as the Nintendo 64.[100][101] Nintendo also introduced a slightly altered controller for it, with the console's logo replaced by an embossed Nintendo logo.[94]

Yellowing

The ABS plastic used in the casing of some older Super NES and Super Famicom consoles is particularly susceptible to oxidation with exposure to air. This, along with the particularly light color of the original plastic, causes affected consoles to quickly become yellow; if the sections of the casing came from different batches of plastic, a "two-tone" effect results.[102] This issue may be reversed with a method called Retrobrighting, where a mixture of chemicals is applied to the case and exposed to UV light.[103]

Game cartridge

Super NES games are distributed on ROM cartridges, officially referred to as Game Pak in most Western regions,[104] and as Cassette (カセット, Kasetto) in Japan and parts of Latin America.[105] Though the Super NES can address 128 Mbit,[lower-alpha 9] only 117.75 Mbit are actually available for cartridge use. A fairly normal mapping could easily address up to 95 Mbit of ROM data (48 Mbit at FastROM speed) with 8 Mbit of battery-backed RAM. Most available memory access controllers only support mappings of up to 32 Mbit. The largest games released (Tales of Phantasia and Star Ocean) contain 48 Mbit of ROM data,[106][107] and the smallest games contain only 2 Mbit.

Cartridges may also contain battery-backed SRAM to save the game state, extra working RAM, custom coprocessors, or any other hardware that will not exceed the maximum current rating of the console.

Games

1757 Super NES games were officially released: 717 in North America (plus 4 championship cartridges), 521 in Europe, 1,448 in Japan, 231 on Satellaview, and 13 on Sufami Turbo. Many Super NES games have been called some of the greatest video games of all time, such as Super Mario World (1990), The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past (1991), Final Fantasy VI (1994), Donkey Kong Country (1994), EarthBound (1994), Super Metroid (1994), Chrono Trigger (1995) and Yoshi's Island (1995).[108][109][110] Many Super NES games have been rereleased several times, including on the Virtual Console, Super NES Classic Edition, and the classic games service on Nintendo Switch Online. All Game Boy games are playable with the Super Game Boy add-on. Many Super NES emulators have been produced. Mode 7 is a graphics mode that can simulate simple 3D effects.

Peripherals

The Super NES controller design expands on that of the NES, with A, B, X, and Y face buttons in a diamond arrangement, and two shoulder buttons. Lance Barr created its ergonomic design, and he later adapted it in 1993 for the NES-039 "dogbone" controller.[82][83] The Japanese and PAL region versions incorporated the four colors of the face buttons into the system's logo. The North American version's buttons were colored to match the redesigned console; the X and Y buttons are lavender with concave faces, and the A and B buttons are purple with convex faces. Several later controller designs have elements from the Super NES controller, including the PlayStation, Dreamcast, Xbox, and Wii Classic Controller.[111][112][113] This face button layout is on future Nintendo systems since the Nintendo DS.

Several peripherals add to the functionality of the Super NES. Some are required by certain games, such as the Super Scope light gun, and the Super NES Mouse for a point and click interface. Various third-parties, under license from Nintendo, released multitap adapters connecting up to five controllers into a single console, starting with the Super Multitap by Hudson Soft in conjunction with the Super Bomberman series. Specialized third-party controllers, such as the AsciiPad and Super Advantage (the successor to the NES Advantage) by Asciiware, and the Capcom Fighter Power Stick, an arcade-like joystick controller by Capcom designed specifically for Street Fighter II. Unusual controllers include the BatterUP baseball bat, the Life Fitness Entertainment System (an exercise bike controller with built-in monitoring software),[114] the TeeV Golf golf club,[115][116] and the Justifier (a revolver-shaped light gun made by Konami for Lethal Enforcers).

Though Nintendo never released an adapter for playing NES games on the Super NES, the Super Game Boy adapter cartridge allows games designed for Nintendo's portable Game Boy system to be played on the Super NES. The Super Game Boy touts several feature enhancements over the Game Boy, including palette substitution, custom screen borders, and access to the Super NES console's features by specially enhanced Game Boy games.[117] Japan also saw the release of the Super Game Boy 2, which adds a communication port to enable a second Game Boy to connect for multiplayer games.

Like the NES before it, the Super NES has unlicensed third-party peripherals, including a new version of the Game Genie cheat cartridge designed for use with Super NES games.

Soon after the release of the Super NES, companies began marketing backup devices such as the Super Wildcard, Super Pro Fighter Q, and Game Doctor.[118] These devices create a backup of a cartridge, and can be used to play illicit ROM images or to copy games, violating copyright laws in many jurisdictions.

The Japan-only Satellaview is a satellite modem attached to the Super Famicom's expansion port and connected to the St.GIGA satellite radio station from April 23, 1995, to June 30, 2000. Satellaview subscribers could download gaming news and specially designed games, which were frequently either remakes of or sequels to older Famicom games, and released in installments.[119] In the United States, the relatively short-lived XBAND allowed users to connect to a network via a dial-up modem to compete against other players around the country.

Nintendo attempted partnerships with Sony and then Philips, to develop CD-ROM-based peripheral prototypes for the console to compete with the Sega CD. Sony produced a Nintendo Play Station prototype which was canceled, diverting this inertia into its own PlayStation console. The Philips project was canceled without a prototype but Philips retained the contractual right to develop games based on Nintendo franchises, which it published for its CD-i multimedia console.[120][121]

Enhancement chips

As part of the overall plan for the Super NES, rather than include an expensive CPU that would still become obsolete in a few years, the hardware designers made it easy to interface special coprocessor chips to the console, just like the MMC chips used for most NES games. This is most often characterized by 16 additional pins on the cartridge card edge.[122][123]

The Super FX is a RISC CPU designed to perform functions that the main CPU can not feasibly do. The chip is primarily used to create 3D game worlds made with polygons, texture mapping and light source shading. The chip can also be used to enhance 2D games.[124]

The Nintendo fixed-point digital signal processor (DSP) chip allowed for fast vector-based calculations, bitmap conversions, both 2D and 3D coordinate transformations, and other functions.[125] Four revisions of the chip exist, each physically identical but with different microcode. The DSP-1 version, including the later 1A and 1B bug fix revisions, is used most often; the DSP-2, DSP-3, and DSP-4 are used in only one game each.[126]

Similar to the 5A22 CPU in the console, the SA-1 chip contains a 65C816 processor core clocked at 10 MHz, a memory mapper, DMA, decompression and bitplane conversion circuitry, several programmable timers, and CIC region lockout functionality.[124]

In Japan, games could be downloaded cheaper than standard cartridges, from Nintendo Power kiosks onto special cartridges containing flash memory and a MegaChips MX15001TFC chip. The chip manages communication with the kiosks to download ROM images and has an initial menu to select a game. Some were published both in cartridge and download form, and others were download only. The service closed on February 8, 2007.[127]

Many cartridges contain other enhancement chips, most of which were created for use by a single company in a few games.[126]

Reception and legacy

Approximately 49.1 million Super NES consoles were sold worldwide, with 23.35 million of those units sold in the Americas and 17.17 million in Japan.[7] Although it could not quite repeat the success of the NES, which sold 61.91 million units worldwide,[7] the Super NES was the best-selling console of its era.

In a 1997 year-end review, a team of five Electronic Gaming Monthly editors gave the Super NES scores of 5.5, 8.0, 7.0, 7.0, and 8.0. Though they criticized how few new games were coming out for the system and how dated its graphics were compared to current generation consoles, they regarded its selection of must-have games to be still unsurpassed. Additionally noting that used Super NES games were readily available in bargain bins, most of them still recommended buying a Super NES.[128] In 2007, GameTrailers named the Super NES as the second-best console of all time (only behind the PlayStation 2) in their list of top ten consoles that "left their mark on the history of gaming", citing its graphics, sound, and library of top-quality games.[129] In 2015, they also named it the best Nintendo console of all time, saying, "The list of games we love from this console completely annihilates any other roster from the Big N."[130] Technology columnist Don Reisinger proclaimed "The SNES is the greatest console of all time" in January 2008, citing the quality of the games and the console's dramatic improvement over its predecessor;[131] fellow technology columnist Will Greenwald replied with a more nuanced view, giving the Super NES top marks with his heart, the NES with his head, and the PlayStation (for its controller) with his hands.[132] GamingExcellence also gave the Super NES first place in 2008, declaring it "simply the most timeless system ever created" with many games that stand the test of time and citing its innovation in controller design, graphics capabilities, and game storytelling.[133] At the same time, GameDaily rated it fifth of the ten greatest consoles for its graphics, audio, controllers, and games.[134] In 2009, IGN named the Super NES the fourth-best video game console, complimenting its audio and number of AAA games.[111]

Emulation

Super NES emulation began with VSMC in 1994, and Super Pasofami became the first working Super NES emulator in 1996.[135] During that time, two competing emulation projects, Snes96 and Snes97, merged to form Snes9x.[124] In 1997, ZSNES development began.[136] In 2004, Bsnes development began with the goal of preservation through maximal accuracy and compatibility, and was renamed to Higan.

Nintendo of America maintained its stance against the distribution of Super NES ROM image files and the use of emulators as it does with the NES, insisting that these things represent flagrant copyright infringement.[137] Emulation proponents assert that the discontinued hardware production constitutes abandonware status, the owners' right to make a personal backup, space shifting for private use, the development of homebrew games, the frailty of ROM cartridges and consoles, and the lack of certain foreign imports. Nintendo designed a hobbyist development system for the Super NES, but never released it.[138]

Unofficial Super NES emulation is available on virtually all platforms, such as Android,[139] iOS,[140][141] game consoles, and PDAs.[142] Individual games have been bundled with official dedicated emulators on some GameCube discs, and Nintendo's Virtual Console service for the Wii introduced diverse and officially licensed Super NES emulation.

The Super NES Classic Edition was released in September 2017 following the NES Classic Edition. This emulation-based mini-console, which is physically modeled after the North American and European versions of the Super NES, is bundled with two Super NES-style controllers and 21 games, including the previously unreleased Star Fox 2.[143]

Notes

- Kent says that September 1 was planned but later rescheduled to September 9.[31] Newspaper and magazine articles from late 1991 report that the first shipments were in stores in some regions on August 23,[32][33] and it arrived in other regions at a later date.[34] August 23 is also the release date officially recognized by Nintendo of America.[35]

- Though the use of "Super Nintendo" is common in colloquial speech and Nintendo of Europe's website,[13] Nintendo of America's official guidelines discourage it, preferring instead the shorthand "Super NES", as written on many of its products such as Super NES Control Deck, Super NES Controller, Super NES Mouse, and Super NES Multi-Player Adapter.[14]

- The name "SNES" can be pronounced by English speakers as an acronym (one word, like "NATO") with various pronunciations, an initialism (a string of letters, like "IBM"), or as a hybrid, like "JPEG". In written English, the choice of indefinite article ("a" or "an") is therefore problematic.[15]

- Japanese: スーパーファミコン, Hepburn: Sūpā Famikon, officially adopting the abbreviated name of its predecessor, the Famicom

- Korean: 슈퍼 컴보이; RR: Syupeo Keomboi

- In both The Ultimate History of Video Games and Purple Reign: 15 Years of the SNES, the disparity in sales is directly attributed to the Super NES version lacking the excessive blood which was recolored grey and described as "sweat", and lacking some of the more gruesome finishing moves. See the Talk page for details.

- Some contend that Nintendo orchestrated the Congressional hearings of 1993, but Senator Lieberman and NOA's Senior Vice President (later Chairman) Howard Lincoln both refute these allegations.[58]

- Japanese: スーパーファミコン ジュニア, Hepburn: Sūpā Famikon Junia

- Unless otherwise specified, kilobyte (KB), megabyte (MB), and megabit (Mbit) are used in the binary sense in this article, referring to quantities of 1024 or 1,048,576.

References

- "Retro Diary: 08 November – 05 December". Retro Gamer. No. 122. December 13, 2013. p. 11.

- "Super Nintendo Entertainment System (Platform)". Giant Bomb. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- "History | Corporate". Nintendo. Archived from the original on September 4, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- C. Portilla (November 21, 2015). "Los juegos más recordados a 25 años del lanzamiento de la Super Nintendo". La Tercera. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- "Nintendo chega hoje ao mercado". O Estado de S. Paulo. August 30, 1993. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "Соглашение Steepler и Nintendo". November 1994. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- "Consolidated Sales Transition by Region" (PDF). Nintendo Co., Ltd. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- Reisinger, Don (January 21, 2009). "Does the Xbox 360's 'Lack of Longevity' Matter?". CNET. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- Wolf, Mark J. P. (November 21, 2018). The Routledge Companion to Media Technology and Obsolescence. Routledge. ISBN 9781315442662. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- Niizumi, Hirohiko (May 30, 2003). "Nintendo to end Famicom and Super Famicom production". GameSpot. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2007.

- "The Nintendo Years: 1990". Edge. June 25, 2007. p. 2. Archived from the original on August 20, 2012. Retrieved June 27, 2007.

- "Platinum Titles". Capcom. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2010.

- Nintendo of Europe. "Super Nintendo". nintendo.co.uk. Archived from the original on August 20, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- "SNES Development Manual" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- "Do you say NES or N-E-S?". Nintendo NSider Forums. Archived from the original on May 5, 2008. Retrieved September 23, 2007. Additional archived pages: 2 3 4 5 8 9 ; "Pronouncing NES & SNES". GameSpot forums. Archived from the original on February 14, 2012. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- Brian Byrne, Brian (2017). History of the Super Nintendo (SNES): Ultimate Guide to the SNES Games & Hardware. Console Gamer Magazine. p. 4. ISBN 978-1549899560.

- Brian Byrne, Brian (2017). History of the Super Nintendo (SNES): Ultimate Guide to the SNES Games & Hardware. Console Gamer Magazine. p. 5. ISBN 978-1549899560.

- Coelho, Victor (November 24, 2014). "Super Nintendo completa 24 anos" [Super Nintendo turned 24 years old]. Exame (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on November 6, 2018. Retrieved June 3, 2018.

- Sheff (1993), pp. 353–356. "The Genesis continued to flounder through its first couple of years on the market, although Sega showed Sisyphean resolve.... [By mid-1991] Sega had established itself as the market leader of the next generation."

- Kent (2001), pp. 413–414.

- Mensch, William David, Jr. (November 10, 2014). "Oral History of William David "Bill" Mensch, Jr" (PDF) (Interview). Interviewed by Stephen Diamond. Mountain View, California: Computer History Museum. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 20, 2015. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

{{cite interview}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fahey, Rob (April 27, 2007). "Farewell, Father". Eurogamer. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- Covell, Chris. "Super Famicom: August 1988". Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- "スーパーファミコン発売前夜". Niconico (in Japanese). August 1, 2013. Archived from the original on July 9, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- Covell, Chris. "The First Super Famicom Demonstration". Archived from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- Covell, Chris. "The Second SFC Demonstration". Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- Kent (2001), pp. 422–431.

- Sheff (1993), pp. 360–361.

- Kent (2001), pp. 431–433. "Japan remained loyal to Nintendo, ignoring both Sega's Genesis and NEC's PC Engine (the Japanese name for TurboGrafx).... Unlike the Japanese launch in which Super Famicom had outsold both competitors combined in presales alone, Super NES would debut against an established product."

- Kristan Reed (January 19, 2007). "Virtual Console: SNES". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- Kent (2001), p. 432.

- Campbell, Ron (August 27, 1991). "Super Nintendo sells quickly at OC outlets". The Orange County Register.

Last weekend, months after video-game addicts started calling, Dave Adams finally was able to sell them what they craved: Super Nintendo. Adams, the manager of Babbages in South Coast Plaza, got 32 of the $199.95 systems Friday.

Based on the publication date, the "Friday" mentioned would be August 23, 1991. - "Super Nintendo It's Here!!!". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 28. Sendai Publishing Group. November 1991. p. 162.

The long awaited SNES is finally available to the U.S. gaming public. The first few pieces of this fantastic unit hit the store shelves on August 23, 1991. Nintendo, however, released the first production run without any heavy fanfare or spectacular announcements.

- "New products put more zip into the video-game market". Chicago Sun-Times. August 27, 1991. Archived from the original (abstract) on November 3, 2012. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

On Friday, area Toys R Us stores […] were expecting SNES, with a suggested retail price of $199.95, any day, said Brad Grafton, assistant inventory control manager for Toys R Us.

Based on the publication date, the "Friday" mentioned would be August 23, 1991. - Nintendo of America [@NintendoAmerica] (August 23, 2021). "On this day 30 years ago, the Super..." (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Campbell, Ron (August 27, 1991). "Super Nintendo sells quickly at OC outlets". The Orange County Register.

Super Nintendo began showing up in Southern California stores Wednesday, nearly three weeks before the official Sept. 9 release date. ... Until the official nationwide release Sept. 9, availability will be limited.

- "COMPANY NEWS; Super Nintendo Now Nationwide". The New York Times. September 10, 1991. Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- Phillips, Tom (April 11, 2012). "SNES celebrates 20th birthday in UK". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on May 14, 2019. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- "Playtronic SNES Games". SNES Central. Archived from the original on August 9, 2014. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- "Nintendo Brasil" (in Portuguese). Nintendo. Archived from the original on July 17, 2007. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- Sheff (1993), p. 361.

- "Big in Japan: Nintendo 64 Launches at Last". Next Generation. No. 21. September 1996. pp. 14–16.

- Jeremy Parish (November 14, 2006). "Out to Launch: Wii". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on August 4, 2011. Retrieved July 3, 2007.

- Kent (2001), p. 431. "Sonic was an immediate hit, and many consumers who had been loyally waiting for Super NES to arrive now decided to purchase Genesis.... The fiercest competition in the history of video games was about to begin."

- Kent (2001), pp. 448–449.

- Kent (2001), p. 433.

- Hisey, Pete (June 1, 1992). "16-bit games take a bite out of sales — computer games". Discount Store News.

- Kent (2001), p. 496-497. "The late November release of Donkey Kong Country stood in stark contrast to the gloom and doom faced by the rest of the video game industry. After three holiday seasons of coming in second to Sega, Nintendo had the biggest game of the year. Sega still outperformed Nintendo in overall holiday sales, but the 500,000 copies of Donkey Kong Country that Nintendo sent out in its initial shipment were mostly sold in preorder, and the rest sold out in less than one week. It (Donkey Kong Country) established the SNES as the better 16-bit console and paved the way for Nintendo to win the waning years of the 16-bit generation."

- "Game-System Sales". Newsweek. January 14, 1996. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- Greenstein, Jane (1997). "Don't expect flood of 16-bit games". Video Business.

1.4 million units sold during 1996

- "Sega farms out Genesis". Television Digest. March 2, 1998. "Sega of America sold about 400,000 16-bit consoles in N. America last year, based on estimates extrapolated from NPD Group's Toy Retail Statistical Tracking Service. That compares with just over one million Super Nintendo Entertainment Systems (SNES) sold by Nintendo of America."

- Danny Allen (December 22, 2006). "A Brief History of Game Consoles, as Seen in Old TV Ads". PC World. Archived from the original on May 8, 2008. Retrieved July 15, 2007.

- "Classic Systems: SNES". Nintendo. Archived from the original on December 9, 2003. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- Pachter, Michael; McKay, Nick; Citrin, Nick (February 11, 2014). "Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc; Why the Next Generation Will Be as Big as Ever". Wedbush Equity Research. p. 36. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- Kent (2001), pp. 308, 372, 440–441.

- Reeder, Sara (November 1992). "Why Edutainment Doesn't Make It In A Videogame World". Computer Gaming World. p. 128. Archived from the original on January 10, 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2014.

- Ray Barnholt (August 4, 2006). "Purple Reign: 15 Years of the SNES". 1UP.com. p. 4. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- Kent (2001), pp. 461–480. "nearly three to one".

- Kent (2001), pp. 491–493, 496–497.

- Doug Trueman. "GameSpot Presents: The History of Donkey Kong". GameSpot. p. 4. Archived from the original on May 15, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- "Nintendo Boosts N64 Production". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 93. Ziff Davis. April 1997. p. 22.

- Chris Johnston (October 29, 1997). "Super NES Lives!". GameSpot. Archived from the original on January 24, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- "Classic System Gets New Shell". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 102. Ziff Davis. January 1998. p. 22.

- Yutaka Ohbuchi (January 16, 1998). "Super Fami Gets Face-Lift". GameSpot. Archived from the original on January 18, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- "スーパーファミコン (Super Famicom)" (in Japanese). Nintendo Japan. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019. Retrieved May 19, 2007.

- "E3 2005: Nintendo's E3 2005 Press Conference". IGN. May 17, 2005. Archived from the original on February 14, 2012. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- "Nintendo's classic Famicom faces end of road". AFP. October 31, 2007. Archived from the original (Reprint) on May 27, 2013. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- Gwaltney, Javy. "Super Nintendo Games Are Coming To New Nintendo 3DS". Game Informer. Archived from the original on October 18, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- "Nintendo Direct - 09.04.2019". www.nintendo.com. Archived from the original on September 4, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- "NES™ and Super NES™ – Nintendo Switch Online – Nintendo Switch™ Official site". www.nintendo.com. Archived from the original on September 9, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- "Fullsnes – Nocash SNES Specs". Archived from the original on January 2, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- Jeremy Parish (September 6, 2005). "PS1 10th Anniversary retrospective". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on May 23, 2011. Retrieved May 27, 2007.

- Nintendo (1993). "SNES Development Manual - Book I, Section 4 "Super NES CPU Data"". Nintendo. Archived from the original on November 28, 2018. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- "NA » Need help » SNES Gen 1 Video Repair more than 50 units". Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- "Is the SNES a realible console?". Archived from the original on August 17, 2018. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- Hayward, Andrew (March 12, 2017). "The Nintendo PlayStation is the coolest console never released". TechRadar. Archived from the original on September 12, 2018. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

Nintendo and Sony first linked up for the Super Nintendo itself, as Sony produced the S-SMP sound chip for the iconic 16-bit console.

- Nintendo (1993). "SNES Development Manual - Section 3, Super NES Sound". Nintendo. Archived from the original on November 28, 2018. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- Nintendo Life (July 6, 2013). "Soapbox: Why Region Locking Is A Total Non-Issue". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- "The Ultimate Retro Console Collectors' Guide". Eurogamer.net. May 6, 2012. Archived from the original on August 22, 2015. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- Mark Knibbs (December 27, 1997). "Disabling the SNES/Super Famicom "Lockout Chip"". Archived from the original on January 21, 2003. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- Mark Knibbs (January 25, 1998). "Super NES/Super Famicom 50/60 Hz Switch Modification". Archived from the original on May 2, 2001. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- "Super Nintendo Entertainment System". Nintendo Power. Vol. 25. Redmond, Washington: Nintendo of America. June 1991. pp. 45–46.

- Margetts, Chad; Ward, M. Noah (May 31, 2005). "Lance Barr Interview". Nintendojo. Archived from the original on July 22, 2016. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- "Nintendo Support: Super Nintendo AV to TV Hookup". Nintendo. Archived from the original on August 5, 2016. Retrieved March 2, 2010.

- "Nintendo Support: New-Style Super NES RF to TV Hookup". Nintendo. Archived from the original on May 20, 2010. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- "Nintendo Support: Original-Style Super NES RF to TV Hookup". Nintendo. Archived from the original on March 10, 2010. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- "Nintendo Super System: The Future Takes Shape". Arcade Flyers Archive. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved April 19, 2008.

- "Nintendo Super System on SNES Central". Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- "Nintendo Will No Longer Produce Coin-Op Equipment". Cashbox. September 5, 1992. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- "Nintendo Stops Games Manufacturing; But Will Continue Supplying Software". Cashbox. September 12, 1992. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- Lane, Gavin (July 12, 2021). "Nintendo Hardware Refreshes Through The Ages". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on May 31, 2022. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- "Super Famicom Jr". Nintendo. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- Goulter, Tom (December 3, 2012). "The history of console redesigns". GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on May 1, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- Johnston, Chris (October 29, 1997). "Super NES Lives!". GameSpot. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- Plant, Logan (July 7, 2021). "A History of Nintendo Console Redesigns". IGN. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- Byford, Sam (July 11, 2019). "A brief history of cutdown game consoles". The Verge. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- Buxton, Matt (October 31, 2017). "Powering Up Super Power - Finding The Ultimate SNES Console". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 9, 2023.

- Petty, Jared (August 23, 2016). "27 Sexy Console Redesigns". IGN. Archived from the original on July 9, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- "任天堂、家庭用で 4月に「GBライト」発売 新製品を次々と" (PDF). Game Machine. No. 561. Amusement Press. April 1, 1998. p. 14.

- Ohbuchi, Yutaka (January 16, 1998). "Super Fami Gets Face-Lift". GameSpot. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- "Playing with Power: The Super Nintendo 25 Years On". Retro Gamer. No. 148. Imagine Publishing. November 2015. p. 58. ISSN 1742-3155.

- Edwards, Benj (January 12, 2007). "Why Super Nintendos Lose Their Color: Plastic Discoloration in Classic Machines". Vintagecomputing.com. Archived from the original on January 1, 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2009.

- Dziezynski, James (October 24, 2013). "Retrobright Restoration Project". www.mountainouswords.com. Archived from the original on October 24, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- "Game Pak Troubleshooting". Customer Service. Nintendo of America, Inc. Archived from the original on August 14, 2010. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

- ゼルダの伝説 神々のトライフォース 取扱説明書. Nintendo Co., Ltd. November 21, 1991. p. 1.

- Ogasawara, Nob (November 1995). "Future Fantasies from overseas". GamePro. Vol. 7, no. 11. San Mateo, CA: Infotainment World. p. 126. ISSN 1042-8658.

- "Star Ocean". Nintendo Power. No. 86. Redmond, WA: Nintendo of America. July 1996. pp. 60–61. ISSN 1041-9551.

- Top 100 SNES Games of All Time - IGN.com, retrieved August 11, 2023

- "50 Best Super Nintendo (SNES) Games Of All Time". Nintendo Life. January 30, 2023. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- "The 15 Greatest SNES Games of All Time". Destructoid. February 19, 2023. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- "Top 25 Videogame Consoles of All Time". IGN. September 4, 2009. Archived from the original on March 4, 2010. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- Sud Koushik (January 30, 2006). "Evolution of Controllers". Advanced Media Network. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved May 25, 2007.

- Chris Kohler (September 13, 2005). "Controller's History Dynamite". 1UP.com. p. 4. Archived from the original on September 29, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2007.

- "Use Your Super Nintendo to Play Your Way to Perfect Health". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 67. Ziff Davis. February 1995. p. 54.

- Super Nintendo ( SNES ) Controller – TeeV Golf by Sports Sciences. August 22, 2015. Archived from the original on March 17, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2015 – via YouTube.

- "Popular Mechanics". google.com. Hearst Magazines. March 1995. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- Eric Levenson (April 21, 2014). "Feature: Remembering the Super Game Boy". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on October 25, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- "SNES Backup Units". RED #9. Archived from the original on June 26, 2007. Retrieved September 17, 2007.

- Bivens, Danny (October 27, 2011). "Nintendo's Expansion Ports Satellaview". Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- Edge staff (April 24, 2009). "The Making Of: PlayStation". Edge. Future Publishing. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- "History of the PlayStation". IGN. August 27, 1998. Archived from the original on February 18, 2012. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- "SNES Development--Schematics, Ports, and Pinouts" Archived May 4, 2015, at the Wayback Machine "Many carts connect only to pins 5-27 and 36-58, as the remaining pins are mainly useful only if the cart contains special chips."

- "Super Nintendo Architecture | A Practical Analysis". The Copetti site. June 28, 2019. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- (2007-05-01) Snes9x readme.txt v1.51. Snes9x. Snes9x. Retrieved on July 3, 2007.

- Overload (May 29, 2006). "Digital Signal Processing". Overload's Puzzle Sheet. Archived from the original on March 11, 2007. Retrieved May 9, 2007. Refer to the command summaries for all four DSP versions.

- Nach; Moe, Lord Nightmare. "SNES Add-on Chip information". Archived from the original on July 8, 2007. Retrieved May 9, 2007.

- Robinson, Andy (February 8, 2007). "Nintendo Closes Nintendo Power". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- "EGM's Special Report: Which System Is Best?". 1998 Video Game Buyer's Guide. Ziff Davis. March 1998. pp. 54–55.

- Top Ten Consoles. GameTrailers. April 19, 2007. Event occurs at 9:00. Archived from the original (Flash video) on October 1, 2021. Retrieved September 14, 2017.

- Top Ten Nintendo Systems (Flash video). Gametrailers. March 28, 2015. Event occurs at 10:48. Archived from the original on March 29, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- Reisinger, Don (January 25, 2008). "The SNES is the greatest console of all time". CNET Blog Network. Archived from the original on February 19, 2012. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- Greenwald, Will (January 28, 2008). "The greatest game console of all time?". CNET Blog Network. Archived from the original on February 19, 2012. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- Sztein, Andrew (March 28, 2008). "The Top Ten Consoles of All Time". GamingExcellence. Archived from the original on May 10, 2012. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- Buffa, Chris (March 5, 2008). "Top 10 Greatest Consoles". GameDaily. Archived from the original on March 9, 2008. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- Altice, Nathan (May 2015). I Am Error. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262028776. Archived from the original on April 28, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- "ZSNES v1.51 Documentation". ZSNES. Archived from the original on January 19, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- "Legal Information (Copyrights, Emulators, ROMs, etc.)". Nintendo of America. Archived from the original on June 18, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- "What Does This... Have to Do with This?". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 94. Ziff Davis. May 1997. p. 22.

- Head, Chris (August 12, 2010). "Android: A Gamer's Guide". PCWorld. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- Sorrel, Charlie (January 23, 2008). "SNES Emulator for iPhone". Wired. Archived from the original on March 17, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- Sorrel, Charlie (June 9, 2010). "Video: SNES for iPad, Controlled by iPhone". Wired. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- Werner Ruotsalainen (May 10, 2007). "The definitive guide to playing SNES games on Windows Mobile (and Symbian)". Expert Blogs. Smartphone & Pocket PC Magazine. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- "Nintendo Announces SNES Mini, and it'll Include Star Fox 2". Kotaku UK. Archived from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

Bibliography

- Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- Sheff, David (1993). Game Over: How Nintendo Zapped an American Industry, Captured Your Dollars, and Enslaved Your Children (First ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-40469-4.

External links

Super NES Programming at Wikibooks

Super NES Programming at Wikibooks